| For in much wisdom is much

grief, And he who increases knowledge increases sorrow. Ecclesiastes 1:18 |

VII. MY COMMENTS ON THE MAIN ISSUES INVOLVED

THE MILITARY NECESSITY QUESTION

There is no doubt that the greatest question regarding the evacuation and relocation was whether it was really a "military necessity." Was it military matters that motivated the decision-makers, or was it racial discrimination and war hysteria?

There was no doubt in the minds of most West Coast inhabitants, including those of Japanese ancestry, that something HAD to be done. For the Japanese to remain would have been risky from both a military and a social perspective. Many local officials and business leaders declared they did not want any Japanese living in their area. Even the Japanese American Citizens League requested so (see JACL letter here).

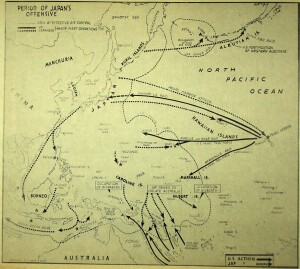

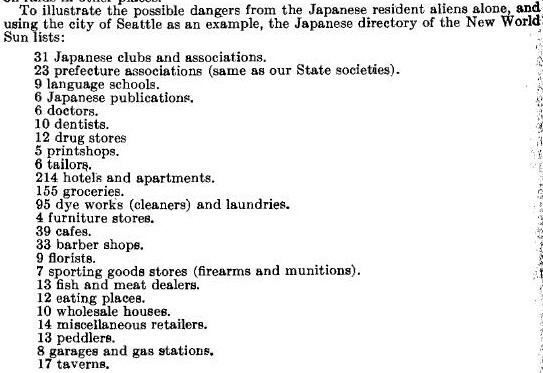

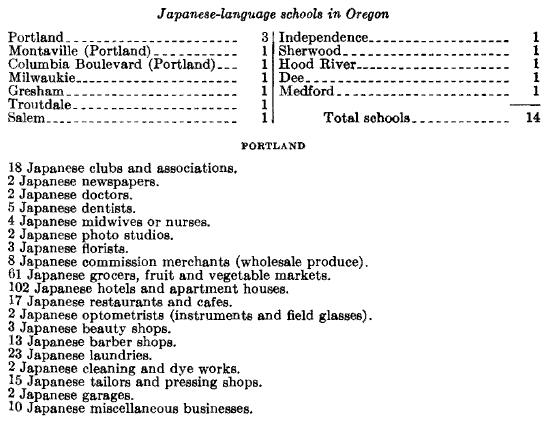

In light of top secret intelligence documents, there were immense concerns by US military leaders that the Japanese posed a great threat to stability on the West Coast. Large networks of Japanese organizations (which had been under surveillance by our intelligence bureaus for many months prior to WWII) were active in intelligence-gathering work. The threat of a West Coast invasion by Japanese forces was very real (Japanese submarine incursions and attacks w/ catapult aircraft, Attu invasion, balloon bombs; also Defense of the Americas) . Were there an invasion, how many resident Japanese would collaborate, willingly or unwillingly? Given the network of Japanese organizations active on the West Coast prior to Pearl Harbor, there was great fear among not only military leaders and personnel, but also civilians -- could these people of Japanese ancestry be trusted, and if so, whom?

With the promise of places of refuge planned for the Japanese, there must have been great relief that they at least had somewhere safe to live and work, with meals and other necessities taken care of, and especially, protected from vigilantes and irate Americans who wanted to get revenge on the Japanese. Primarily, the reception hundreds and thousands of West Coast refugees would receive from inland inhabitants would be the greatest worry (see Myer's testimony at the beginning of TL06-1).

In any society there are those who would betray even their own family. The US, then in a war against Japan, faced this very dilemma -- could the resident Japanese be trusted or would they be a potential threat to society? There were Japanese living in the US who were classified immediately as "enemy aliens" on December 8, 1941. Not only was their nationality a problem, but the fact that many did not speak the English language well nor understand and follow American customs and living habits made them "different" and hence not accepted into society easily. The relocation centers had this problem, and it was almost entirely through the English-speaking Japanese that discussions with the WRA were conducted. The lack of English language ability put the alien evacuees at a great disadvantage, compounded with the fact that they were enemy aliens. (IA094 has good info by Hoover on the evacuation decision pros and cons.)

| The evacuation of all Japanese from the

West Coast to the Interior of the U.S. was made

necessary for reasons of military security. As time was

of the essence, there was no alternative to the action

taken... Despite the improvement in our military

situation and the restoration of the Pacific fleet, the

capabilities of the enemy are such as still to

jeopardize the security of the West Coast. The evacuation of these people did not constitute a determination as to their loyalty or disloyalty, nor did their assembly in the ten Relocation Centers built by the Army, and now administered by WRA, constitute the internment of these people. They are not internees or prisoners of war. It was never the intention of the Government from the beginning to confine all of them in these centers for the duration of the war. It has always been, and still remains, the intention to assist those whose loyalty have been definitely and fully examined and established, to locate themselves as rapidly as feasible elsewhere than on the West Coast, and to resume living under conditions as nearly normal as possible, the same as all other residents of the United States whose loyalties are not doubted. The fact of Japanese ancestry alone is not a reason for continued confinement. That would be racial discrimination. It must be remembered that nearly 25,000 Japanese residents of the U.S., citizens and aliens, have resided elsewhere than on the West Coast for many years, where they have followed various occupations, living in harmony with their neighbors. These have never been in Government Centers. |

The question is often brought up, "Why were only the Japanese put in camps?" Simply stated, other enemy nationals indeed were also put into camps in the US during WWII -- Germans, Italians, Bulgarians, etc. (see IA102 for INS totals; also PDF documents here on statistics; book on American-Italian evacuation here). The primary difference between these other countries and Japan was that Germany or Italy did not attack US territory and kill thousands of our people -- Japan did. There was also no threat of attack on the East Coast from either German or Italian naval forces. There was from the Japanese Navy which then ruled the Pacific. Furthermore, the 1940 US Census shows that there were some 3 million people of German and Italian ancestry living in the United States, making any evacuation process logistically impossible. It should also be noted that many of the recent arrivals of German immigrants to the US were refugees fleeing Nazism.

There was, therefore, the urgent necessity to deal with a group of foreigners within the United States who had suddenly become enemies of our nation. Unfortunately, this included their American-born children, who could not be separated from their parents, and therefore must inevitably share their fate.

For a better understanding on alien residents who became alien enemies, and the constitutionality of the evacuation, read WRA Final Report on Legal and Constitutional Phases of the WRA Program. See also Memoranda on the Constitutional Power of the WRA to Detain Evacuees, especially the 11 points in Opinion No. 3 on the "factual background against which the action was taken."

| There was evidence of disloyalty on the

part of some, the military authorities considered that the

need for action was great, and time was short. We cannot

-- by availing ourselves of the calm perspective of

hindsight -- now say that at that time these actions were

unjustified. Court's opinion in Korematsu v. United

States

|

THE INTELLIGENCE QUESTION

One of the most overlooked issues dealing with the necessity for the evacuation was the intelligence we had on the resident Japanese prior to the decision to evacuate. The US had been secretly reading all Japanese diplomatic electronic messages sent out and received on the West Coast and had accumulated a wealth of information on the activities of the Japanese throughout the US.

Not many people were given daily updates on this intelligence gathered by the various agencies. Even WRA Director Myer was in the dark, and his views and opinions reflected this. It could not have been otherwise -- the military risk was much too great to allow top secret information to be shared by many, and even more, the source of this information. Had Myer been privy to the decrypts, he no doubt would have held a much more informed view regarding the reason the Japanese were evacuated from the West Coast.

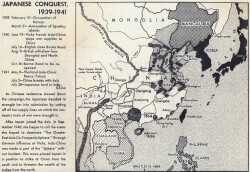

Much criticism is aimed at the leaders -- Roosevelt, Stimson, McCloy, Bendetsen, and DeWitt -- the last of these receiving the major blame for the decision to evacuate those of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. (See Excerpts from an Oral History Interview with Karl R. Bendetsen where he summarizes the reasons for EO9066.) However, it is wise to remember exactly what was happening at that time in the Pacific War where the Imperial Japanese Forces ruled supreme, namely the situation on Bataan and Corregidor, and especially in Singapore, which surrendered to Japanese Forces on Feb. 15, 1942, just days before Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066. No doubt this massive surrender to Japanese Imperialists played a very important role in influencing decision-making on Capitol Hill. It is hard to conceive that the decision to evacuate was the result of any single person, given the magnitude of logistics and expense, not to mention the impact on human lives (see Corps of Engineers estimates).

| It is difficult for people who did not live

through that dreadful time to reconstruct the terror and the

anxiety felt by people along the entire west coast. Disaster

followed upon disaster after the attack on Pearl Harbor. On

that same day, December 7, 1941, Japanese forces landed on

the Malay Peninsula and began their drive toward Singapore.

Guam fell on December 10, Wake on December 23. On December 8

Japanese planes destroyed half the aircraft on the airfields

near Manila. As enemy troops closed in, General MacArthur

withdrew his forces from the Philippines and retired to

Australia. On Christmas day the British surrendered Hong

Kong. The Western World was scared stiff. The west coasts of the United States, rich with naval bases, shipyards, oil fields, and aircraft factories, seemed especially vulnerable to attack. There was talk of evacuating not just the Japanese from the west coast but everybody. Who knew what was going to happen next? -- former Senator S. I. Hayakawa

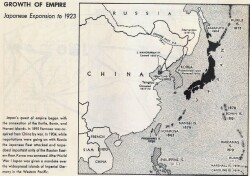

Japanese Imperial Expansionism 1869 - Colonization of Hokkaido 1879 - Colonization of Okinawa 1894 - Taiwan seized (won war with China 1894-1895) 1905 - Kwantung Province (North China) and South Sakhalin (SE Russia) seized (won war with Russia 1904-1905) 1910 - Annexation of Korea Major Japanese Military Conquests Prior to EO9066 1941 Nov. 27 - Japanese fleets depart to attack east and invade west Pacific Dec. 7 - Japan attacks: * Pearl Harbor (Vice Adm.

Nagumo's Striking Force)

Invades:* Wake Island and Guam (Adm. Inoue's 4th Fleet) * Philippines (Gen. Homma's 14th Army from Formosa; elements from Palau) * Siam (Thailand) and Malaya

(Gen. Yamashita's 25th Army and Imperial Guards Division)

Dec. 8 - Japan takes Gilbert Islands* Hong Kong (locally based Japanese forces) Dec. 10 - Japan takes Guam Dec. 11 - Japan invades Burma (Gen. Iida's 15th Army) Dec. 16 - Japan invades Borneo Dec. 22 - Japan invades Philippines Dec. 23 - Japan invades Wake Island Dec. 24 - Battle of Makassar Strait Dec. 25 - Hong Kong surrenders Dec. 31 - Japan occupies Manila 1942 Jan. 11 - Japan invades Dutch East Indies Feb. 15 - Singapore surrenders Chronology of Events on Dec. 7-8, 1941 December 8, 1941 [Japan Time]: 0015 Grew sees TOGO, reads message to him, and asks for appointment to deliver it to the Emperor personally 0045 The Shanghai Bund occupied 0140 Kota Bharu [Malaya] shelled 0200 Komura asks to see Hull 0205 Japanese land at Kota Bahru 0300 Nomura asks for appointment meeting with Hull 0305 Japanese land at Singora and Patani (Siam) 0320-25 attack on Pearl Harbor 0405 Nomura arrives at Hull's office 0420 Nomura hands Hull the document terminating negotiations 0520 H.M.S. Peterel sunk 0530 Japanese troops invade Siam from French Indo-China 0610 air raid on Singapore 0700 Tokyo radio given first notice that hostilities have begun 0730 Grew calls on TOGO, who hands him copy of document handed by Nomura to Hull, stating it was Emperor's answer to President's message 0800 Craigie see TOGO at his request and is handed a copy of the last-mentioned document 0805 Guam attacked 0900 Hong Kong attacked 1140 Japan announced her attack on Hong Kong 1140~1200 Imperial Rescript issued 1150 Japan announced her attack on Malaya 1300 Japan announced her air raid on Hawaii and others 1700 Japan announced her air raid on the Philippines 2100 Japan announced her air raid on airdromes in the Philippines and advance into Thailand -- From IMTFE Proceedings,

Exhibit #001

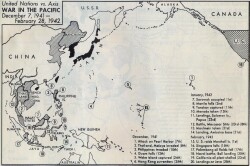

December 7, 1941 [US Time]: Japanese attack on PEARL HARBOR and other positions in PACIFIC opens war between U.S. and AXIS Powers. MIDWAY - Shelled by enemy surface forces estimated at 12 ships. WAKE - Attacked by 24 VB(M) from MARSHALLS. GUAM - Attacked by 30 planes from SAIPAN. PHILIPPINES - Attacked by planes from FORMOSA and PALAU. All U.S. aircraft virtually wiped out. HONGKONG - Attacked by planes from CHINA and attacked by ships and troops. SINGAPORE - Attacked by Japanese planes. THAILAND - "Invaded" by Japs. CHINA - Japanese intern U.S. nationals and Marines and British nationals at SHANGHAI and TIENTSIN. December 8: U.S., GREAT BRITAIN, and NETHERLANDS declare war on Japan. MALAYA invaded. PRINCE OF WALES and REPULSE sunk by Jap. aircraft off MALAYA. OCEAN and NAURU Islands bombed. MAKIN and TARAWA, in GILBERTS, invaded. Attacks continue on WAKE, GUAM, PHILIPPINES, HONGKONG, SINGAPORE. --From US

Navy

Dept. Chronology

For more details, read Japan Assaulted More Than Pearl Harbor. Worst Week

This was the worst week of the war. The nation took one great trip-hammer blow after another—vast, numbing shocks. It was a worse week for the U.S. than the fall of France; it was the worst week of the Century. Such a week had not come to the U.S. since the blackest days of the Civil War... At week's end, Singapore fell. The Axis had broken through. The nation now had only shreds of hope in the Far East... Up & down the country editorial writers, living close to the people of their own communities, worried more about apathy than the collapse of morale. They wrote with bold strokes: AMERICA CAN LOSE; THE WAR CAN BE LOST; THIS SHOULD AWAKEN US. --- TIME Magazine, Feb. 23, 1942

Secret State Matter:

Memorandum of the Conference between the German Foreign

Minister and Ambassador Oshima

on 24 June 1942 in

Berlin

The Japanese Navy probably still has such important tasks to solve as the strengthening of the Japanese position in Australia, to push to the Indian Ocean, securing the position facing, or in, Hawaii, as well as in the Aleutians. If new heavy blows could be administered to the Americans and English there, this would be of great importance to the joint prosecution of the war. It would be of especial importance if we could join hands somewhere in the Indian Ocean in the not too distant future. The German Foreign Minister was not aware of Japan's plans in this regard. (IMTFE Doc. No. 1372) |

It is also important to consider that many of FDR's ideas were not carried out, e.g. the bombing of Tokyo in 1940 (see Roosevelt's Secret War by Persico). There were many other leaders who were decision-makers at the time. Hence, DeWitt or FDR or Stimson were not individually responsible for US Government policy or actions. Remember: It was the entire Congress which enforced the exclusion orders (Public Law 503, March 21, 1942). Our checks-and-balance system worked then just as it works now. Much more can be said about Franklin D. Roosevelt, who ranks among the greatest of our US Presidents, and the only President to have been elected to four terms in office (1933-1945) -- an extraordinary man for extraordinary times.

For further background information, see On the Japanese Problem (1921) and also the Report on Japanese Activities (1942).

Japanese Expansion in 1923 |

Japanese Conquest 1939-1941 |

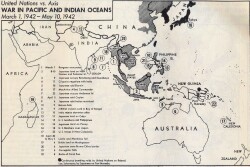

Pacific War Dec 1941 - Feb 1942 |

Pacific War March - May 1942 |

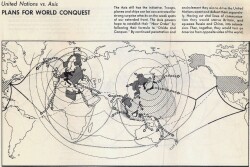

Axis Plans for World Conquest |

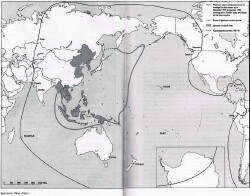

Greater East Asian Sphere (Morganhauser, 2010) |

For more more background information on the Pearl Harbor attack, see the webpage on FDR and Churchill.

PREJUDICES AND DISCRIMINATION

The problem with dealing with incidents in the past is that we in more modern days tend to base our ideas, opinions, and suppositions on our own current conditions, without truly looking at the past with respect to conditions and thinking at that time, putting ourselves into that era's thought frame. It's easy to label past mistreatment as discriminatory in light of what we have seen in our days. Prejudice is very subjective -- what is normal for one person is not for another. To say "all (ethnic group) are hard workers" would probably on the whole be accepted without a complaint, but to state "all (ethnic group) are sneaky" would elicit strong disapprovals. Why? Both are true for a certain number of the ethnic group; the latter is obviously negative, and therefore repulsive to many. It is a matter of qualification, much the same way a statement like "All Americans eat pizza" must be qualified. Much of the prejudices directed against persons of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast was due to years of Asian immigration and along with those immigrants a culture which was most foreign to the majority of ethnic-European Westerners. Policies were formed that showed to the general population that Asians were harming the existing culture and therefore needed to be controlled by laws.

There is much mention made of anti-Japanese organizations, e.g. the Native Sons of the Golden West, the American Legion, etc., and their rhetoric to cleanse the West of this particular ethnic group. Unfortunately the impression was given that all Americans wanted the Japanese out -- another myth that had to be addressed, and which Myer did (see TL42).

The bottom line is this: It was not the US Government which "forced" the Japanese out of their homes and fields; it was first of all the Japanese Imperialists who started the war that made Japanese nationals in the US sudden enemies. Secondly, it was the American people, who thought "their" America was too good a place for the likes of that yellow race which couldn't be trusted, who were here first, who didn't appreciate those who couldn't speak English or didn't act like Americans, who stayed only among their own kind. Granted, State governors and other top officials did not want the evacuees initially due to the war fervor. However, many did change and asked ("begged" could be used here) for evacuee labor due to the demand for manpower in agriculture and other industries. Nevertheless, discrimination and prejudice were still a part of American life, and the blame could not be laid at the feet of the Government. It is typical even today to blame the Government for the faults of the people.

It is most interesting to note that it was the US military (which was singled out as the main culprit for "forced removal") that employed a great number of Japanese-Americans, and many of those were Kibei, who were previously singled out as perhaps the most likely to be pro-Japanese, and not without good reason, per FBI reports, e.g. IA073, IA068). Yet a number of these same Kibei were sent to work in intelligence in the Pacific during WWII (total of 3,000 Nisei in Army Intelligence). In one report it is stated that the Office of Military Intelligence "recruited a large number of evacuees from the relocation centers for further training in language schools." A most intriguing study would be to delve into this whole area of Japanese-Americans in the service of the country. Much has been written about the Nisei soldiers of the 100th and 442nd; much more could be written about Nisei civilians working in other branches of the US Government.

It would be beneficial for anyone interested in the immigration problems of today to read through these pages and see how the situation was handled then with Japanese immigrants. Their policies and efforts may have application today (e.g. see TL43).

Perhaps the greatest credit for acceptance of the Japanese into American society after WWII can be placed with the Nisei and Sansei. They lived with and endured the discrimination and prejudice, and helped show the society around them how baseless their bias was. Scores of their books are available for validating this.

As long as there are humans on earth, there will be wrongful discrimination and racial prejudice, just as thievery, lying and adultery will continue. All nations have a group of people they discriminate against -- in fact, the Japanese themselves discriminate against the Koreans and "burakumin," though this problem has become more open and admitted by many. Racism is just as real today as it was in the first half of the 20th century.

Ironically, there was discrimination, jealousies and outright hatred among the Japanese in the centers (see IA202 re Tayama; also much on this in Soga). The loyal were hated by the disloyal, the Issei and Nisei and Kibei disagreed with each other on many things, the hatred of inu ("dog" in Japanese; used for informants), the intimidation of the Issei & Kibei on those who wanted to join the armed service, etc. -- a taboo subject today among not a few Nikkei.

| The most famous quote attributed to DeWitt is

"A Jap's a Jap. It makes no difference whether the Jap is

a citizen or not." (E.g. JACL Curriculum and Resource

Guide.) The same quote is featured in the Smithsonian

Institution's exhibit... Neither the guide nor the exhibit

offers a citation for the quote -- because no such

actual quote exists. In a telephone conversation with

Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy, transcribed on Feb.

3, 1942, DeWitt said: "Out here, Mr. Secretary, a Jap is a

Jap to these people now" (emphasis added). In this

instance, DeWitt was characterizing Californians'

sentiments, not necessarily his own -- though he repeats the

phrase "A Jap's a Jap" later on in the transcript while

explaining to McCloy the security difficulties faced by the

troops. More than a year later, in public testimony before

the House Naval Affairs Committee, DeWitt stated that ethnic

Japanese still posed a threat to the West Coast and vital

installations. "The danger of the Japanese was, and is

now -- if they are permitted to come back -- espionage and

sabotage. It makes no difference whether he is an American

citizen, he is still a Japanese. American citizenship does

not necessarily determine loyalty." When modern day

ethnic activists and historians cite the "A Jap's a Jap"

quote, the heavy-handed implication is that DeWitt's use of

the term "Jap" -- offensive now, but common in his time --

makes him an unreconstructed racist. There are numerous

instances of Attorney General Francis Biddle, who opposed

evacuation, using the term "Jap." -- From In Defense of Internment

by Michelle Malkin, pg. 337, note 42 |

CONCENTRATION CAMP?

After reading through the following pages, you will immediately be struck at how much effort went into making the relocation centers as comfortable as possible, within reason, of course, and bearing in mind the restrictions of wartime shortages and rationing. From living quarters to meals to fire prevention to hospitals, much thought went into the planning and activation of services for nearly every aspect of life at the centers. That the inhabitants were treated as prisoners, constantly under watch by armed guards, is something written as well as photographic history will find hard to prove.

Furthermore, there are no recorded cases of attempted escapes at night, tunnels dug under the fences for such purposes, smuggling weapons in and out of the centers, or even mob uprisings to break out of their confines. The reason is simply because there were no concentration-camp-like confining fences nor containment measures employed at the centers -- the residents were able to freely leave the centers for farm labor, athletic events and even walks and hikes out in the countryside. Barbed wire with 45-degree top brackets (inward slant specifically for stopping escapees) was used at Tule Lake for only the segregation area. See the assorted quotes below for comments by those who were there.

There were internment camps for persons who were arrested for different reasons. These were located in various areas around the US. The reasons for being there were such as those involved in disruptive activity, demonstrations at the centers, violence against other evacuees, etc. (e.g. Manzanar and Poston). Bendetsen, who was directing the entire program of evacuation and relocation, said, "Internment was never intended. The intention and purpose was to resettle these persons east of the mountain ranges of the Cascades and Sierra Nevada, away from the sea frontier and away from the relatively open boundaries between Mexico and the states of Arizona and New Mexico." Myer has a piece on this here where he describes the three types of centers. See also Wikipedia definitions.

Therefore, it is quite puzzling as to why so many authors prefer to use the terms "internment" and "internees" for those in relocation centers rather than the terms "relocation" and "evacuees." Internment was entirely different and internees were under entirely different confinement conditions, being run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Internment meant there were enemy aliens held and the possibility of their deportation. It is odd to think, if the centers were in actuality internment camps, that the US Govt. intended to deport over 100,000 Nikkei (though there was the suggestion by some who were anti-Japanese). Remember: The centers were run by a civilian organization (WRA), the internment camps by the US Govt. (INS), and the detention camps by the US Govt. (Army).

Granted, the term "concentration" does mean a group of people concentrated in a single area. The question is: why use this term when it was not used at the time? There is obviously an agenda on the part of those who insist these were concentration camps to magnify the suffering, deprivation and degradation the internees faced, to prove just how wrong the US Govt. was.

What is overlooked is this clear fact: the evacuees were provided with nearly every facility and service that a city would provide -- Federal and local government; electricity, water and sewage, police, fire and ambulance services, judicial, postal, banking, telephone, markets, schools, education and recreational centers, libraries, newspapers, and on and on. These were cities, not simply relocation centers, but cities, built in a matter of weeks, an accomplishment deserving much commendation, all paid for and supported by taxpayer funds.

For a very enlightening comparison, read the report on Raton Ranch, Civilian Detention Station (IA124). It would be a most interesting drama to read how the "detainees" at this station and those in charge of them developed lasting friendships, given the nature of the situation there.

A constant theme in most descriptions of the centers is that of being treated as prisoners with barbed wire fences around the centers and guard towers manned with machine guns and/or rifles. A quick perusal of actual photographs of each camp surroundings will show a somewhat contrary atmosphere. I thought this one was an especially poignant:

"Closing of the Jerome Relocation Center, Denson, Arkansas. Clara Hasegawa and Tad Mijake take a last look at the Jerome Center from the balcony of one of the camp's guard towers. The towers have not been manned since segregation was completed during the latter part of 1943 and have been popular with the young folks as a place of rendezvous. This young couple will take up their new residence at the Rohwer Center." (06/19/1944)

For a full view of that tower, see this photo; another view of that lone tower here; also the Topaz tower; famous water tower at Minidoka; Santa Anita Park Assembly Center tower with machine gun. More towers and plenty of barbed wire were at the Tule Lake Segregation Center, needed for the evacuees who were "troublemakers," and others, along with their families, that were segregated there from other centers. See TL26 for more in-depth information on that center. Look at this photo of Tule Lake and note placement of towers -- more appropriate for fire rather than people control. Note also type of fence construction. Here is another photo of the high-security Tule Lake Segregation Camp, different from the original Tule Lake Center.

There are many references to barbed wire in the following documents: IA073, TL06-6 (see photo there), TL10, TL13, TL19, and TL32. Some centers were initially set up with fences around the perimeter, but were of much different height and quality as those around concentration camps. Signs were used at many of the centers, but photos of those are even hard to come by. Note in this photo the fence at Manzanar -- not typical at all, if this were indeed a "concentration camp" intended to keep occupants in. See also this fence at the Topaz Center. Two interesting photos taken at Heart Mountain show the fence and an excursion outside the fence.

It is interesting to note that for the two riots that occurred at centers, one at Manzanar and the other at Poston, guards were called in only at Manzanar. Had they been constantly watching the interior of the centers from their supposed "towers with machine guns," they would have quelled the gathering at an early stage with probably no violence ensuing.

In reality, fences and guard towers around the relocation centers is a moot point since there were 10's of 1,000's of evacuees laboring outside of the centers in the numerous expansive farm fields. These had no barbed wire fences or guard towers (nor armed guards for that matter). Furthermore, the few search lights on these towers indicates that there was no need to keep any of the occupants of the centers under surveillance, even at night, a time during which breakouts and other clandestine activity would normally be expected. The initial assembly centers were a different story, of course, as well as the Tule Lake Segregation Center, where vigilance was very important.

For a good comparison of what the situation was like for our POWs in Japan, see my Fukuoka POW website, especially the pages showing what the US Recovery Team saw when they arrived right after the war. For an excellent comparison of civilians in internment under the Imperial Japanese, see Lou Gopal's website, Victims of Circumstance - Santo Tomas Internment Camp. The DVD is a must-view. Another very moving film is So Very Far From Home about civilian internees in China. Additional information on civilian internees in Japan can be found on my POW website, the main page being this table on Civilian Internment Camps in Japan. Also, read this excerpt from the Tokyo War Crimes Trials in which a Japanese POW tells of the kind treatment he received from the US military.

| I emphasize this last point

because the relocation centers were not "concentration

camps." The younger generation of Japanese Americans

love to call them concentration camps. Unlike the Nazis, who

made the term "concentration camp" a symbol of the ultimate

in man's inhumanity to man, the WRA officials worked hard to

release their internees, not to be sent to gas chambers, but

to freedom, to useful jobs on the outside world and to get

their B.A. at Oberlin College. By 1945, there were almost 2,500 Nisei and Issei in Chicago, a city that was most hospitable to Japanese, and I myself found relatives I did not know existed. Other Midwest and Eastern cities acquired Japanese populations they did not know before the war: Minneapolis, Cleveland, Cincinnati, New York, Madison, Wis., Des Moines, St. Louis, and so on. And those who remained in camp in most cases did so voluntarily. These were the older people, afraid of the outside world, with the Nation still at war with Japan. I point out these facts to emphasize the point that to call relocation centers concentration camps, as is all too commonly done, is semantic inflation of the most dishonest kind, an attempt to equate the actions of the U.S. Government with the genocidal actions of the Nazis against the Jews during the Hitler regime. As an American I protest this calumny against the Nation I am proud to have served as an educator and even prouder to serve as a legislator. -- former Senator S. I. Hayakawa, in

his prepared statement at

the Japanese

American Evacuation Redress Hearing, July 27,

1983

|

BARREN DESERTS AND HARD TIMES

Many refer to some of the centers as being in barren deserts. In reality, all the centers had sufficient water supplied via lakes and streams, and distributed via irrigation ditches. A quick look at the maps and aerial photos of the

relocation areas is sufficient to convince one that

agriculture played a very important part in the lives of the

evacuees. For instance, Manzanar, often portrayed in photos as stark

and dusty, had a thousand apple and pear trees already there that

were cared for by the evacuees when they moved in, and these same

trees ended up producing thousands of dollars worth of fruit.

[PHOTO: "Florence Yamaguchi (left), and Kinu Hirashima, both from

Los Angeles, are pictured as they stood under an apple tree at

Manzanar." (Manzanar, 06/01/1942)]

relocation areas is sufficient to convince one that

agriculture played a very important part in the lives of the

evacuees. For instance, Manzanar, often portrayed in photos as stark

and dusty, had a thousand apple and pear trees already there that

were cared for by the evacuees when they moved in, and these same

trees ended up producing thousands of dollars worth of fruit.

[PHOTO: "Florence Yamaguchi (left), and Kinu Hirashima, both from

Los Angeles, are pictured as they stood under an apple tree at

Manzanar." (Manzanar, 06/01/1942)]Center farms produced tens of thousands of dollars of produce which was shipped to other relocation centers. For instance, the Gila River center in Arizona converted some 7,000 acres from alfalfa to vegetable crops -- hardly what could be expected of a desert location. Tule Lake, incidentally, with its fertile soil, produced 1,300 tons of vegetables in a single harvest, 30% of which was for their own consumption, 60% for other centers, and the remainder sold on the market. For further evidence of this agricultural marvel, see these Crop, Vegetable, and Livestock Production charts. See also IA066 on the prerequisites for choosing suitable locations for the relocation centers.

Human nature enjoys pity, admiration for going through the worst -- "Oh that must have been awful for you. How terrible that you were treated so inhumanely!" There are quite a few books on the subject that depict a variety of woeful experiences at the various centers. I take excerpts, mostly the words of Issei, from Gesensway and Roseman, Beyond Words (one chapter of which is entitled, "It was the Best Times of our Lives") to show the brighter and plausible reality of the whole episode:

Atsushi KikuchiFor more comments by a first-generation Japanese, see Through the Eyes of an Issei: The Internment of Japanese in the United States during World War II, a compilation of excerpts from Yasutaro Soga's memoirs, Life Behind Barbed Wire.

I never volunteer to talk about evacuation unless somebody asks about it. Not because of the experience, but because afterwards I felt it was a real miserable time. Perhaps it benefited the Japanese Americans in the sense that prior to the war they were concentrated in California, and a lot of the Japanese wouldn't mingle. Because of the evacuation, there was a chance for the Japanese Americans all over the United States. Now you can go any place and find Nisei. That probably would have never happened unless the relocation sent them out to the East and Midwest. I think it was good in that respect. Maybe the war would have done the same thing.

Henry Sugimoto

Some people are so bitter. I am, of course, so worried and anxious that I was going to camp. So worried. But when I went to camp, I'm rather happy, you know, because I can do my work and do what I like. If I can still make my art, I am feeling not so bitter. I'm artist, and I can do my work any place, anywhere. Other people have quite a different feeling; that's just my feeling.

So then we left camp for New York. A minister -- he was commissioned to visit camp to camp -- when he came to visit my camp, he always came to see me. And he said, "Mr. Sugimoto, where do you want to go? You want to go back to California?" And I said, "No, I am artist. If I can, I want New York." That's best, because New York not so much discrimination. Before the war, we had so much discrimination. So mostly, people go to New York or Chicago -- they're all spreading after the war, all spreading.

Hiro Mizushima

The barrack itself was just tar paper on the outside. We had a pot belly stove; Arkansas did get pretty cold. The inside was just bare wood walls and there were cots, just like army cots. The floor was just bare. I remember air coming through the bottom. But I have to give the Issei and the Japanese people a lot of credit because they did something with it. Even these dull-looking black tar paper covered barracks became attractive after a time. They put gardens in front of them and all that. Rohwer was in a wooded area and it was quite nice. So it wasn't as bad as people might think and still it wasn't as good.

Togo Tanaka

My constant and repeated reference to that fence is perhaps unfair because it seems to leave so little room for all the happy things that went on and continued to go on within the relocation camps. But these happened in spite of and not because of it.

Charles Mikami

A lot of people wanted to go back to Japan, and I told them, "Don't go back. Japan has hard times now -- America bomb; everything flat." You got to use your head. "Don't go back. You'll want to come back to America again." But at that time, you can't come back. People would say, "Japan's better, Japan win," like that, you know. I say, "No, I don't think so" They say, "You're terrible; you're pro-American" "No, I'm not pro-American. Japan now has big battleships and strong army, but Japan has no oil, no rubber. Maybe keep up for a while, but they can't go on. So I don't think so." But "Mr. Mikami's pro-American," they say So I got to keep my mouth shut. I don't say anything. Just painting, no meetings. I'm instructor of art, that's enough. So I had a nice time in the camp -- quiet.

Jack Matsuoka

When the school first opened, they didn't have teachers, no books. So just go to class to hear somebody talk, that's about it. I had my heart set on going to college, but once I got in the camp I gave up studying totally. It's so hot and so crowded, we all went outside to sleep. We'd talk, just talk all night long -- about girls, sports, boys, the army. Next day, you had a hard time getting up. So for us kids, just get up, eat, and play, that's all. Every now and then have a dance party. So it wasn't that bad for us.

Sports were real important. We'd get up and play basketball, baseball. I was on the basketball team and I helped coach football. I remember we had to buy our own baseball and basketballs from Sears, and our own uniforms and set up our own league. We had championship playoffs. It's funny, but I think sports were one of the key factors that kept people from going astray, or feeling dissatisfied in camp. If it weren't for those athletic leagues, I think there would have been more dissension.

And the young kids did hate to live with their parents in such close quarters. No place to go, except to the grandstand with their girlfriend or something. In the evening we'd often take a walk around the racetrack for exercise.

Shoes all wore out because of the fine gravel. Pretty soon we wanted shoes badly. They hadn't organized yet so we couldn't order them. So we started making wooden shoes -- getas. They made them quite well. They'd get boards, and old tire rubber, and they put it on the bottom so it doesn't make too much noise and wear out. So I had one made too. I got so that I liked them.

It was a conflict because the Isseis and the Niseis, they're both living close together. Before camp we only went around with the Niseis, we didn't have much to do with the first generation. They were our enemies in a way. Now, that's a funny thing to say, but we didn't like them when we were teenagers. And yet we had to get to know them, had to get along because we were living in the same barrack with just a little paper in between. My neighbor wanted to paint, but he couldn't make the color turquoise, so I helped him, and he helped me. I got to know him, and I thought, well, he's not so bad. These oldsters -- we used to call them oldsters -- they're human, they're nice.

Yuri Kodani

For the kids it was great. We didn't have to get home for dinner because there were mess halls all over and we could just stop in with our friends.

Anonymous

Life in camp really wasn't that bad, especially in Arkansas. Once we got there, the camp started its own farm, growing vegetables. Everybody had a victory garden right by their barracks. And then they had a pork farm also. And everybody had their own jobs -- some people were paid sixteen dollars a month and others were paid nineteen dollars a month -- which was kind of silly. But Sears, Roebuck did a tremendous business! Yes, everybody had a Sears catalogue and ordered things.

Masao Mori

Camp life wasn't too different -- except I had time for sketching... Oh, I enjoy drawing so much I go outside the camp sketching. First three or four months we can't go out, but after a year or so, we can go out all right. I did a lot of sketching outside the camp, I have some sketchings inside.

Lili Sasaki

And of course, Japanese love clubs. We were clubbed to death in all the camps: sewing clubs and poetry clubs and this and that. Right away, we put together a writers' club, artists' club. Even an exercise club. I could get up in the morning, and I could hear them exercising. The Japanese are organizers, right away they are organizing. We also put on plays. We decided we might have dancing -- got all the musicians who could play jazz or records. So we did have a lot of dances. We decided that we are going to have dances and let the people have fun.

"A group of actors in a scene from a play depicting a legendary incident of old Japan, as presented at an entertainment program at this relocation center." (Heart Mountain, 09/19/1942)

Kango Takamura

One time, right in front of RKO Studios, one actor (says), "Your people!" -- points like this at me -- "Pearl Harbor!" He looks terrible, you see. My boss (reprimanded) him so he won't say anything after that. And then (my boss) said, "Hey Tak, this is trouble. You have to watch out. This kind of fellow is all over around there, so you have to watch out." Every day they were so nice. Some people understand so much, sympathize for us. And in the wartime, we don't get any jobs, I think. I hated the fact that I was born in Japan at that time, but only at that time. The Japanese third generation talk lots about it now. They say we were Americans so not supposed to (be interned). But for us, it's very protective, see.

And finally I was released and went to Manzanar. We arrived at Manzanar in the early morning, before sunrise. Beautiful. All pink. The mountains around there were all pink. So beautiful. Yes, I thought this is such a nice place. I joined my wife, and daughter, and her husband, and granddaughter and stayed there three years. I worked so hard there. Every day I enjoy. Usually when I worked in the movie studios I would work eight hours. But every day at the camp, I worked ten hours. I was happy. I moved into a barrack in the very corner, Camp 35. Nobody was there. Just snakes, such a wild place! Only the lumber was laid down, that's all. So we had to tarpaper and put waterlines in.

Really our life was not so miserable. Everyone was writing songs and learning how to paint and studying and writing poems. It is not so miserable a life. After the war is over, people thought it was a miserable place. But it was better than Island people in Japan had, I think, because we at least had plenty of food. Of course, not such good food! Funny thing is that it was not such good food, but very few got sick because of the food. You see, it's not gourmet stuff, but good enough for health. And plenty of water. Japanese people make big baths with cement, and we got in there together, not individually, but five people, seven people, ten people all together. So very nice. In those days, you know, we don't think about wartime. Sometime we forget. It was so peaceful up there. It was very peaceful because the younger people who made too much noise and trouble, they went to another camp (Tule Lake).

My nature doesn't like trouble. I am afraid, you see. I don't want to see any blood. (During the revolt) about fifty people came to my daughter's place to get her husband (Togo Tanaka, who had been identified with the JACL). I was among them because I want to watch my daughter and grandchild. I'm afraid they try to hurt my daughter. The army came after that to protect them, and I took my grandchild to the army car and she cried. So afraid, you see. I said, "Don't you cry, Jeannie!" I scold like this, and she stopped crying. She understood -- only one year old. She stopped right away. "Please take this baby to her family over there," I said. And they took her and moved them to the army camp that night. So we are safe.

George Akimoto

I didn't have any problem because we had a twenty-acre farm. We put everything in the barn. The neighbor, Mr. Doyle, an Irishman, my father knew for sixty years. Mr. Doyle took care of the whole place. In those days (you heard), you know, "Kill the Jap! Kill the Jap!" But he took care of it. He took care of the truck, the farm. He farmed it himself with his kid. He rented the house. This is the reason you don't make a friend with just anybody. You've got to know who you are, who he is.

In the meantime, on my wife's side -- they lived in Fresno -- the whole house was burned down. They had somebody take care of the whole place; there's no alternative. Somebody rented the house or whatever, and burned the whole house down. It's a hard thing to say, whether it's right or wrong to have to go to camp.

Already right after Pearl Harbor there were people carrying guns, looking for the Japs. What good is it when you're shot? The Chinese themselves went around wearing little badges that said, "I'm American Chinese." I couldn't tell the difference between the Chinese, Koreans, Japanese. I couldn't tell the difference. But they made the difference. They put the badges on, I felt it's for safety. It's dangerous in those days. The people were so panicked, confused. They didn't know what to do. I thought it's better off just to go, it's for our own safety. My family, my wife's family, nobody got shot. But people did. That's what the government said, it's for our own protection. Also, there's nothing you can do. It's the same sort of situation like when you're drafted into the army. You just have to go.

Before the evacuation I was just trying to make something. I wanted to do something. My father was a farmer. We had a twenty-acre farm. Get up at five o'clock in the morning, plow the fields, work like that. I decided I didn't want to farm. I decided to go to college. I went to two years at Pomona College. But I hear about these people who go to college, get a degree, and then can't get a job. The Japanese people finally have the money to send their kids to college. But when you get out of college in those days, there's no job because of what they call prejudice. They will not hire Japanese. So we end up working in the fruit markets or something like that. So I said, "The heck with that." That's what happened. So I said, "I quit." I decided I was going to be a real professional, and I went to art school.

I didn't start that war. ****! I didn't start the war. But what can I do? They put us in the camp. You can't do anything in the camp -- no painting, no nothing. The thing is you have to make the best of it in the camp. I wasn't carrying any chip on my shoulder against the government or anything. No. It's the condition; you have to get used to it. My father and mother were in there for three years.

Gene Sugioka

When the first evacuees came to the relocation camp -- they are from Terminal Island, mostly from Los Angeles, and they move into Poston #1 -- these Arizonians, a truckload of men with shotguns, travel from Parker to the camp. They're going to shoot them (the evacuees) all. So, it's a good thing they had a MP; he stopped them.

The problems in the camps came from what they called the age gap. In the camp they had a struggle between young and old. One of the young people says, "The **** with it; I can't stay in this camp," and they just take off. They volunteer for the army. But the old man Issei says, "No, the government took us to the relocation camp like this. We're going to go back to Japan." Oh, then they had a fight!

And it's not just the age gap, it's culture. There are two different cultures in the camp: the Nisei, and the Issei and Kibei. It's a hard thing. I'm right in the middle. What can I do? And then, they have -- I think it's the most important part of the whole camp situation -- the government published pamphlets which asked two questions: "Are you loyal to the United States?" and "Will you bear arms to fight for your country?" Oh, this is the big issue. Oh, boy! Most people, Issei, say, "Why should you say 'yes'? The government put us in the camp." But what can the Nisei do? You can't go around speaking your views openly because this Kibei will came out there in the middle of the night and grab you and cut your hair off. He shaved the whole hair off of the Nisei. Yes, I guess my wife was always worried about that. She said, "Don't go out there in the middle of the night."

Dr. Leighton used to come up in his Navy uniform with the lieutenant stripes on it to visit me at lunchtime. He sat next to me eating lunch. All the people look at me and call me a dog. (The Issei and Kibei) think that I'm supposed to be an agent or something because Dr. Leighton was in a uniform and comes in and talks to me or something. Then this guy, old timer, comes in and says, "How do you write your last name?" He says, "When Japan conquers the whole United States, when they're going to win the war, you'll be in the first ones going to be hanged!"

In the meantime, this old man, making that kind of statement, what do you think his son does? His son volunteers for the army -- went to Italy. The Issei was up and down, crying. He's going around camp apologizing to older people -- "Why did my son do a thing like that?" Apologizing to other people. I said, "No, it's not wrong. He has his own opinion. He has a right to live his own way." Oh when I saw that.... We're in the same boat, that's what I'm trying to tell these people. We're in the same boat. Why can't we work together? Oh, some radical people!

One time, they had an incident. They had a big protest, something about food. That was in Camp 1; I was in Camp 2. Camp 1 is early evacuees from Terminal Island. They have a strong group of Isseis, pro-Japan; a group in the middle, like I am; and a third group who don't care, never get involved. They're fighting each other because one has the power or wants it. They had a big strike. See this flag over here? These are groups of Kibei -- pro-Japan. They're having a rally. Some people want to elect me for the block manager. But I don't want to. It's not worth it. I didn't want to be involved. So much political party fighting.

We go fishing in the Colorado River. I like fishing; I still do today. A lot of Japanese people like fishing. It's the only place you could relax -- fishing or something like that in the Colorado. Walked four miles through all the mesquite wood and the rattlesnakes. And this guy -- this is very important -- this representative from California named (John M.) Costello, he's on what they call in those days the Dies Committee. He comes to the camp; it was his order to see what goes on there, I suppose. Well, he finds a piece of Wonderbread bag on the riverbank where we were fishing. So you use a little bread for bait, that's it. This Costello made a report. He said that Japanese were waiting for a submarine coming up the Colorado River! I don't think it's funny; it's crazy! Even today I think why didn't they put the Italians and the Germans in the camps? But the point is the majority of the population is Italians and Germans and you can't do that to the population. Because we are a minority...

"During the noon hour, evacuee farm workers fish for

carp in a nearby slough." (Tule Lake, 09/08/1942)

Some say we shouldn't be in relocation camps. We are American citizens. I don't feel like that. The conditions we were in with the war and this and that.... You can't carry a chip on your shoulder. It's wrong. I mean it's wrong in the black and white, what you write on the piece of paper. Unconstitutional. But when you talk about how you feel about it, I really don't know. It's something else. I really don't know.

CITIZENSHIP AND POPULATION

It must be kept in mind that nearly all of the American citizens in the relocation centers were under 35 years of age, with the largest group being between 10 and 25. About 35% of the entire population were NOT American citizens, and comprised the majority of the parents of those who WERE American citizens, and the majority of those young people were under 20 years of age. In other words, the youth (Nisei and Sansei) outnumbered their elders (Issei), the majority of the evacuees being young people. No doubt the idea that U.S. citizens were "incarcerated" or "interned" conjures up negative connotations, making it sound as if they were POWs. In reality, they were children of alien parents, and naturally, the great majority of them could not be separated from their parents.

(There were 110,000 Nikkei who were affected by EO9066 and under the WRA -- 38,000 Issei (over half from southern Japan) and 72,000 Nisei. Of those Nisei, 41,000 were 19 yrs. of age and under.)

So just who were these evacuees? Mostly young people, who were mostly American citizens. It is therefore interesting to note the number of recent books written about life at the centers are by those who were youth at the time, some just toddlers. How they viewed the centers naturally would be considerably different from how their parents saw the situation.

Due to the large number of young citizens, they naturally were eligible for positions in the government of the centers, to the chagrin of the elders, who were non-Americans. This added even more unrest among the classes of people at the centers. Much could be written about the cultural clashes between the two generations, why the parents didn't move somewhere else when they could have, and so on.

Here are some statistics on the number of children who were also registered with the Japanese Govt., hence having dual citizenship:

45

PERCENT

OF CHILDREN REGISTERED

AS JAPANESE SUBJECTS

AS JAPANESE SUBJECTS

Out of 39,310 births of children of Japanese ancestry registered at the Japanese consulate since 1925, 17,825 registered to become Japanese subjects, taking advantage of dual citizenship.

The record by years follows:

1925 - males, 744; females, 648; total, 1,392.

In 1926 - males, 1,842; females, 1,751; total, 3,593.

In 1927 - males, 1,530; females, 1,465; total, 2,995.

In 1928 - males, 1,582; females, 1,443; total, 3,025.

In 1929 - males, 889; females, 835; total, 1,724.

In 1930 - males, 681; females, 644; total, 1,325.

In 1931 - males, 611; females, 575; total, 1,188.

In 1932 - males, 490; females, 492: total, 982.

In 1933 - males, 449; females, 403; total, 825.

In 1934 - males, 407; females, 371; total, 778.

Grand total, 17,825.

Since 1929 the public schools at the primary grades insist that all children who enter the elementary grade shall show a birth certificate. This, it is said, has had a far-reaching effect on parents in reducing registration of their children with the Japanese consulate.

From 1925 until 1934, 5,676 American citizens of Japanese ancestry have been expatriated from Japan. The year-by-year figures are:

In 1925, 402 males; 85 females; total 487.

In 1926, 430 males; 108 females; total, 538.

In 1927, 285 males; 51 females; total, 336.

In 1928, 234 males; 32 females; total, 266.

In 1929, 205 males; 19 females; total, 226.

In 1930, males, 218; females, 18; total, 236.

In 1931, males, 261; females, 29; total, 290.

In 1932, males, 902; females, 346; total, 1,248.

In 1933, males, 1,204; females, 323; total, 1,527.

In 1934, males, 484; females, 133; total, 614.

Grand total, males, 4,624; females, 1,144; both males and females, 5,768.

It will be recalled that there was much agitation in 1932 and 1933 against dual citizenship, and the large increase in expatriation during the years, as shown by the tables, is believed to have resulted from that agitation.

-- Investigation of Un-American

Propaganda, Appendix VI,

Report on Japanese Activities, p. 2000 (1942)

Report on Japanese Activities, p. 2000 (1942)

| "To encourage the proudest Japanese national spirit which

has ever existed, to fulfill the fundamental principle

behind the wholesome mobilization of the Japanese people,

to strengthen the powers of resistance against the many

hindrances which are to be faced in the future, and to

realize this permanent peace in the Far East which will

bring happiness and security to the Asiatic people and make

firm the foundation of our mother country, the Great

Japanese Empire, as the proudest nation in the world.

We who are unable to accomplish our important objective as

soldiers on the battle front must adopt the special method

of the Long-Term-Donation policy and in this way assist in

financing the war with the utmost effort on the part of

both the first and second generation Japanese and whoever

is a descendant of the Japanese race. Now is the time

to awaken the Japanese national spirit in each and everyone

who has the blood of the Japanese race in him. We now

appeal to the Japanese in Gardena Valley to rise up at

this time." --- From purpose of the "Compulsory

Military Service Association," Gardena, Calif. Branch;

January 15, 1942 (see IA060) |

YES-YES, NO-NO -- THE QUESTIONNAIRE

Another issue raised is a Selective Service questionnaire comprised of a total of 28 questions, the last two becoming most controversial in that they asked all evacuees 17 years of age and over about their loyalty and allegiance to the United States and to Japan. The sole purpose of the questionnaire, part of a Selective Service registration process, was fundamentally to determine who was loyal to the US and who was pro-Japanese. Having this information, the WRA would then know who could be released from the centers for induction into the military, and also who to segregate (15,000 were moved to Tule Lake using the questionnaire results). Another similar but more in-depth questionnaire was for leave clearance to go to work on war-related industrial projects or simply for relocating out of the centers (see related TL05 and Leave Clearance Interview Questions.)

The initial wording for Question #28 caused confusion for some (Tule Lake), and so it was re-worded and labeled #28-A:

INITIAL: "Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attacks by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese Emperor or any other foreign government, power or organization?"It can be clearly seen the intent of the questionnaire: to determine who would be loyal to the U.S. in the event of a Imperial Japanese military invasion of the West Coast, and who would be considered a possible collaborator. Wartime vigilance required extra precaution, especially in view of the fact that Japan had the most powerful Navy in the Pacific, and indeed controlled for the most part the whole Pacific region, and the potential for attack and invasion was quite real, even though diminished after the Coral Sea and Midway battles. (See IA012 for more information.)

RE-WORDED #28-A: "Will you swear to abide by the laws of the United States and to take no action which would in any way interfere with the war effort of the United States?"

The big unknown was trust -- who among the Nikkei in the US could they trust? As in any society, it only takes a few troublemakers to cause laws to be made which affect everybody. In the same way, the Nikkei who were engaged in espionage and other clandestine activities put a black mark on the whole population of those of Japanese descent.

The situation in the centers was changing -- Nisei were being more and more influenced by the Issei and Kibei (see IA031). Easily moldable minds of youth were most susceptible to the constant talk of the elders, now that they were together daily and learning more of the old ways of Japan and its language. The need for determining just which side of the fence the Nisei were on was great, and the questionnaire was one way to find out. (See info on loyalty in IA106.)

It may be mentioned here that one of the things many bring out is the fact that no Nikkei was ever convicted of espionage or sabotage. (Using the same reasoning, equally ridiculous, one can also say that no Nikkei was found innocent of espionage or sabotage.) The real issue is that there were thousands of Japanese who were placed into detention and internment camps for their alleged involvement in subversive operations, but none of them were brought to trial -- for obvious reasons of security, as the incriminating evidence was still top secret then. See FBI reports of those under investigation and info on their activities on the West Coast; also MAGIC decrypts; also see IA021 (esp. re Tachibana Case), IA059, IA024, IA040, IA211a and IA235 for FBI & ONI reports; also G-2 Bulletin on Japanese Espionage. For actual cases against Japanese Americans, see Kawakita; also other surprising info in Nakahara as well as in this collection on Nisei in the Emperor's service. Further research can be found on fifth-column activity in Japanese-resident countries in SE Asia, e.g. the Philippines and Malay.

| The Japanese diplomatic and military codes had been broken

in secret during 1941. This intelligence named MAGIC

conclusively established the clear military necessity for

President Roosevelt's act. It revealed the existence on the

Pacific coast of massive espionage nests utilizing Japanese

residents, citizens and noncitizens. -- Karl Bendetsen

|

The Japanese Government probably had their hopes on the Nisei in the event that war broke out between the two countries -- the Issei would not be of much help in espionage work since they would be placed under immediate watch as enemy aliens. They were greatly disappointed to have their hopes dashed by the quick arrest of suspected Japanese and the evacuation of all the rest. The extent to which the Japanese were evacuated in the US bears greatly on the extent to which the Imperial Govt. of Japan were able to utilize intelligence gathering and surveillance in the US. We had broken many of their codes, and they had not done the same with ours, fortunately. We guarded that secret well. Had we dealt with the Nikkei in the US any other way would have revealed too much info which we had derived from broken coded messages. This could very well be the reason many of the military leaders in the US became scapegoats and took the blame rather than reveal their true sources of intelligence.

The results of this questionnaire are most interesting, in view of all the uproar: of all those who registered for the questionnaire (3,000 did not), nearly 97% of the Issei, 74% of the male Nisei, and 85% of the female Nisei answered "Yes" to Question #28 (TL-21). See below for more thoughts on this topic.

RECIPROCATION AND EXCHANGE

Japan was closely watching the internment, evacuation and relocation of the Issei (also called hojin, Japanese nationals; another term commonly utilized was doho, fellow countrymen or compatriots, e.g. nihonjin doho, kaigai doho or zaibei doho; yamato minzoku was another term) and Nisei in the US, and no doubt affected their policy toward treatment of Allied POWs and civilian internees in Japan -- see TL21, TL23, TL32 Japanese Diet quote, TL33 propaganda, IA012, IA202 in several places, and also these books on the Gripsholm exchanges, Quiet Passages by Corbett and Japanese-American Civilian Prisoner Exchanges by Elleman. There may have been a great turn of events in how Japan treated our POWs in their hundreds of camps had some of the media organizations in the US not spewed forth their anti-Japanese rhetoric so vehemently. This may be another interesting study in this whole complex issue -- the effect of the US media portrayal of the evacuation and relocation program on the Japanese Imperial Government (see TL26). Interestingly, there was a request by the State Department that a Nisei accused of espionage NOT be prosecuted "until the agreement entered into between this Government and the Japanese government for the reciprocal repatriation of nationals has been carried out" (see IA040).

Had there been no unrest at the centers, many US civilians in Japan could have potentially returned on repatriation ships. The problem would have been, though, whether Japan would have really agreed to more civilian exchanges as they were stepping up their use of Allied POW labor. But if the ill behavior of those individuals in the relocation centers did in fact influence the Japanese Govt.'s hard-line attitude, much blame can be laid at the feet of those instigators. The question can be asked, however -- Did the Japanese Govt. actually want any of her hojin nationals returned? Most of the Issei wanted to stay in the US anyway (see TL48).

Also consider: To have allowed the evacuees to relocate too early, or to certain areas, may have led to acts of violence against them by the anti-Japanese faction, which certainly would have then influenced the Imperial Japanese to retaliate against our POWs. One must realize that these type of things were constantly taken into consideration by our leaders -- not only concerning the welfare of the evacuees but also our POWs in Japan.

|

WASHINGTON WATCH

By Cliff Kincaid September 1995 "As we commemorate the 50th anniversary of V-J Day, we pay tribute to one of the proudest eras in American history -- the triumph over Japan's aggression in Asia. We should take a moment to remember the men and women who put their lives on the line to keep America's place in the world." -- Senate Republican Leader Bob Dole "If World War Il marked the world’s darkest hour, It was also our most noble. The spirit that defined the war, the spirit of sacrificing for the common good, remains a powerful lesson for us today. World War Il taught us that we can overcome any obstacle -- if we are united." -- Senate Democratic Leader Thomas A. Daschle As Americans celebrate the end of World War II, there are lingering questions about whether the U.S. government itself appreciates the sacrifice our veterans made. As just one recent example, the Enola Gay controversy, in which the Smithsonian Institution sought to portray Japan as the victim in World War II, convinced many that there are powerful forces in today’s American bureaucracy who want to keep the facts of Japanese aggression hidden from public view. More evidence: In writing his book about Japanese war crimes, Prisoners of the Japanese, historian Gavan Daws says he was amazed that official U.S. government sources completely neglected the issue of Japanese atrocities committed against Allied POWs. Gilbert M. Hair, a survivor of the Japanese POW camps who heads up the Center for.Civilian Internee Rights, adds that of all the Allied nations, "The U.S. government is at the bottom of the list in terms of holding Japan accountable." Hair’s group has filed suit against the Japanese government in an effort to win reparations. Perhaps it is understandable why the Japanese would still refuse to issue a full public apology for starting the war and then brutalizing Allied prisoners. But why, many people ask, does our own government seem so reluctant to come to grips with the Japanese role? One possible answer: It appears, says Daws, that at the end of the war, a decision was made to recast Japan as a U.S. ally, likely as a strategic bulwark against the Soviets. This policy was also reflected in the decision to exempt from war-crime prosecution Japanese military officers in charge of germ-warfare programs, in exchange for their knowledge of chemical and biological agents. These programs were shrouded in secrecy until the details of hideous medical experiments conducted on American and Allied POWs were disclosed in Daws’ book and elsewhere. Today, Daws tells the AMERICAN LEGION MAGAZINE, there may be other geopolitical reasons why Japan is not being compelled to own up to its unsavory past. Maybe Washington doesn’t want to further complicate the sensitive trading relationship between the two countries. Or, perhaps Washington is counting on Japanese support against increasingly militaristic foes like China and North Korea. In any event, Daws says he doesn't see why international pressure should not be put on the Japanese. Indeed, one of his book's prime goals was mobilizing ordinary citizens to persuade the government to force Tokyo to apologize for its dreadful acts. “How could the U.S. or Japan be damaged by [such an apology]?” he asks. “The U.S. govemment,” he points out, “has already apologized to Japanese-Americans interned on U.S. soil." Actually that understates the case. In 1988, President Reagan signed into law a bill that gave $20,000 payments and letters of apology to Japanese-Americans who were removed from their homes during the war, Lillian Baker, a renowned historian, calls the passage of the bill a national scandal; the campaign got so intense, she alleges, that veterans’ groups were warned not to protest the legislation or else they risked having their benefits cut. She describes it as a “rush job,” signed into law even before the legislation was printed and available for study. As a result, she notes, the first 495 payments under this bill ended up in Tokyo in the hands of known “alien enemies and American traitors.” So why did the bill pass? “It was a guilt trip,” charges Baker. “Nobody wanted to be accused of racism.” As further proof, she observes that Washington paid off only Japanese-Americans, even though other ethnic groups -- German- and Italian-Americans -- were also interned. If guilt is a factor in this subtly pro- Japanese diplomacy, political pressure is another. “The Japanese have the biggest lobby in Washington,” says Baker. The 1990 book, Agents of Influence by Pat Choate, underscores her point. Not only does Japan spend $400 million a year buying influence, but Choate details how pro-Japanese materials are flooding U.S. schools. The influence extends even to Hollywood -- whose output, of course, helps shape public opinion. “There must be 1,000 movies depicting what the Nazis did in World War II,” says Hair of the Center for Civilian Internee Rights. “There’s less than 100 that focus on what happened in the Pacific.” Any film that smacks of anti-Japanese sentiment faces rough seas, he argues, and he illustrates with the case of Michael Crichton’s best-selling 1992 thriller, Rising Sun, which portrayed Japan in an unfavorable light. When the film rights were put up for sale, none of Hollywood’s powerful Japanese-owned studios even placed a bid. This trend is not likely to abate soon -- not with Japan continuing to buy into the upper echelons of American culture. Nevertheless, long-time observers are optimistic that the mood, at least in Washington, is changing. Among new members of Congress in particular, says Hair, the feeling is, “The Japanese have gotten a free ride for too long.” (Washington-based Cliff Kincaid writes for Human Events and other publications.) |

PRESERVATION OF A PEOPLE

On the whole, it could very well be said that the evacuation of the Nikkei from the Western Defense Command designated military areas resulted in their preservation from harm, danger, loss of possessions, and even possibly, loss of their lives. Had they remained in their homes, they would have been the constant targets of harassment due to war reports on Imperial Japanese victories and the cruel treatment of American POWs (see section here in TL04). They had already been subject to increasing immigration and other assorted restrictions through the preceding decades, so to the non-Japanese in their communities it would be considered normal to impose even greater restrictions, such as jailings, or even worse, lynching.

Those very neighbors could even have eventually set up their own internment camps to deal with their enemy alien neighbors, and who knows how much more dire their conditions would have been. In view of the war-time American feelings towards Japan and her people, the centers were indeed refuges from harm and danger, for which all those who lived there should be thankful. A good example of how the Nikkei were protected from mob violence, see this report on the Raton Ranch camp where they were "very happy" and "wished to remain" at this "small country community."

Furthermore, having just come out of the Great Depression during which thousands lost their farms, their jobs, and many of their possessions, the Nikkei were suddenly given a new lifestyle which was comparatively worry-free -- no need to be concerned about a job, food, shelter and medical attention for the entire family. It was a life quite advantageous in many ways, no doubt a subject of envy by outsiders, and something again for which the Nikkei can be grateful.

| ...to provide for residents of any such area who are excluded therefrom, such transportation, food, shelter, and other accommodations as may be necessary... including the furnishing of medical aid, hospitalization, food, clothing, transportation, use of land, shelter, and other supplies, equipment, utilities, facilities, and services. |

FILLING THE NEED

The evacuees at the centers were not just on the welfare roll or on the taking end of things. One of the greatest benefits America received at home during WWII through the Nikkei was their agricultural labors. As stated earlier, they not only produced great quantities of food, but, due to manpower shortages throughout the US during the war, they worked on farms to help harvest crops which would have been left to rot otherwise, e.g. the sugar-beet crop, which later helped somewhat to ease sugar rationing (see first part of TL21). There are many other industries in which the relocatees worked and helped America win the war (see WRA short films, A Challenge to Democracy (1944), Japanese Relocation (1943)).

THE IRONY

The very ones who did not want the Japanese living in their neighborhood were the very ones who ended up supporting them in the relocation centers, all paid by their taxes. Myer realized this in many of his reports, commenting on the burden the care of over 100,000 people places on US taxpayers (see TL21, TL22, TL23, TL27 Letter to Truman, and TL34). He therefore felt the relocation program should be carried out to completion by allowing all residents to return to normal living conditions outside the centers. In this, he was most successful.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

In closing, I present these major points to consider:

1. Japan's unprovoked sneak attack on a US territory was the primary cause of the entire evacuation program, whereby it brought into existence a state of war between Japan and the United States, and hence, citizens of both nations becoming enemies.One of the remarkable things during my research has been my discovery -- somewhat sad, though quite understandable -- that Nisei for the most part had and still have trouble with the Japanese language -- sad in that they have lost touch with their heritage; understandable in that they prove the power of the American culture. My anticipations of the Nisei, and Sansei for that matter, is unfair, of course -- my father couldn't speak Norwegian, and neither can I, though his father emigrated from Norway; I have, sadly, little interest in that country's culture or traditions. Undoubtedly it is because I have spent so much time in Japan and learned to speak, read and write the language and absorbed as much culture as I could. And that is precisely the reason I view with wonderment so many Japanese in the US who have so little attachment to that land where I, in many ways, grew up.

2. The Imperial Japanese Naval Forces ruled a third of the world, including the Pacific Region.

3. The West Coast was a target for a Japanese invasion.

4. Japanese of non-American citizenship on the West Coast were suddenly enemies. Their children born in the US were unfortunately included due to relation.

5. Language and cultural barriers prevented mutual understanding. Great distrust and malice toward the Japanese became more and more evident and severe.

6. The US military was very much afraid of Imperial Japan westward expansionism; the US public was even more so. Remember... Welles' "War of the Worlds" broadcast was only 3 years earlier and had resulted in mass hysteria.

7. Anti-American activities by Japanese organizations on the West Coast were alarming.

8. Japan's cruel and atrocious treatment of Allied POWs and interned civilians (some 14,000 civilians alone at outbreak of war) was becoming more and more known to the US.

9. The planning of the mass evacuation and relocation was not a spur of the moment decision nor the work of only a few men. The manpower numbers and cost involved was immense, requiring approval from many committees and involving much personnel and tax-payer funding. If there were a more practical and cost-efficient program, and a more just program, it would have been chosen. Furthermore, no one could have fully understood the reasoning and thought processes of the President, Secretary of State, and other military planners of the program, for these were not recorded in any manner, nor perhaps even discussed with anyone.