Nisei in His Imperial Majesty's Service

Japanese Americans Who Served the Fatherland

During World War II

Approximately 20,000 second-generation Japanese (Nisei), born in the

United States, spent World War II in Japan. There were at one time some

50,000 Nisei in Japan; see excerpts

below. Even though they were American citizens, because of a

special law the Japanese Government regarded them as citizens of Japan.

Incidentally, many Nisei in the United States had dual citizenship; in

the Territory of Hawaii alone, some 60% of the Nisei were also Japanese

citizens (i.e. over one-third of Japanese in the territory were dual

citizens). Per a US Navy Dept.

intelligence report: "Out of a total Japanese population of 320,000

in the United States and its possessions, it is estimated that more than 127,000 have dual citizenship.

This estimate is based on the fact that more than 52% of American born

Japanese fall into this category." Per Roehner's

research (2014):

For the 158,000 residents of

Japanese ancestry in the Territory of Hawaii, the figures (in 1940)

were as follows:

- Japanese aliens: 38,000

- Dual Japanese-US citizens:

55,000

- Non-dual US citizens: 65,000

For the 162,000 residents of Japanese ancestry in the continental

United States, the figures (in 1940) were as follows:

- Japanese aliens: 38,000

- Dual Japanese-US citizens:

62,000

- Non-dual US citizens: 62,000

Duplicity

was normal then and no one thought it strange -- but to most Americans

suddenly confronted with an aggressive Japan, it was paramount to being

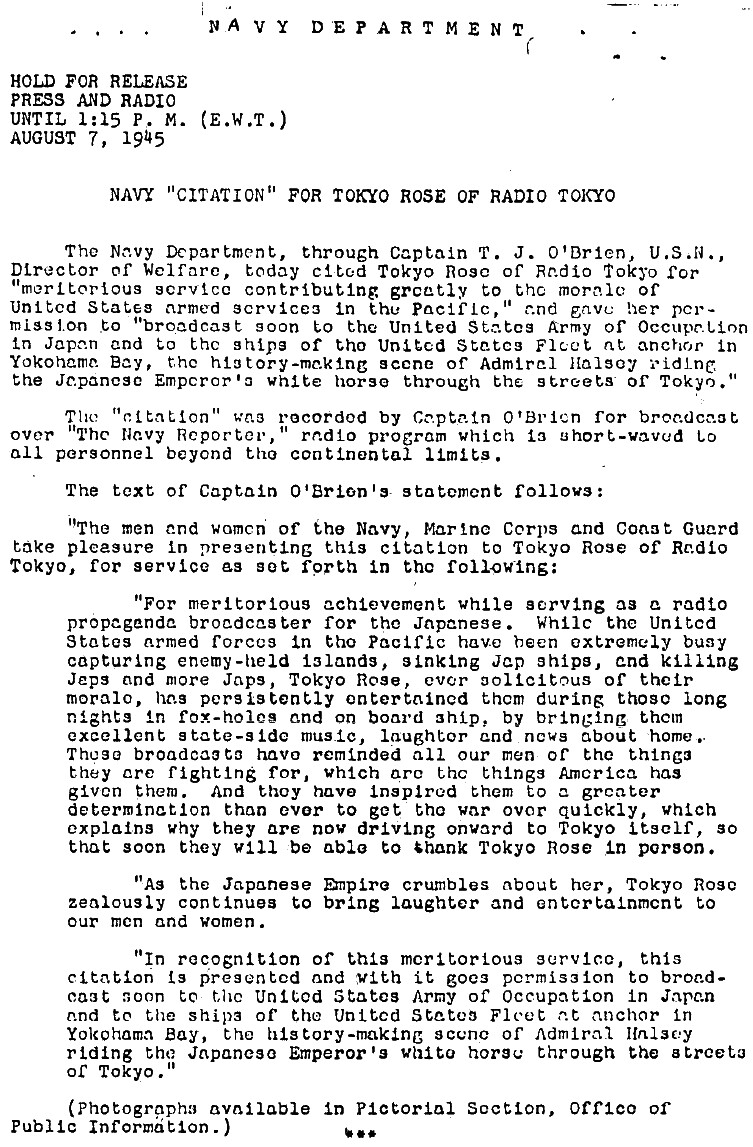

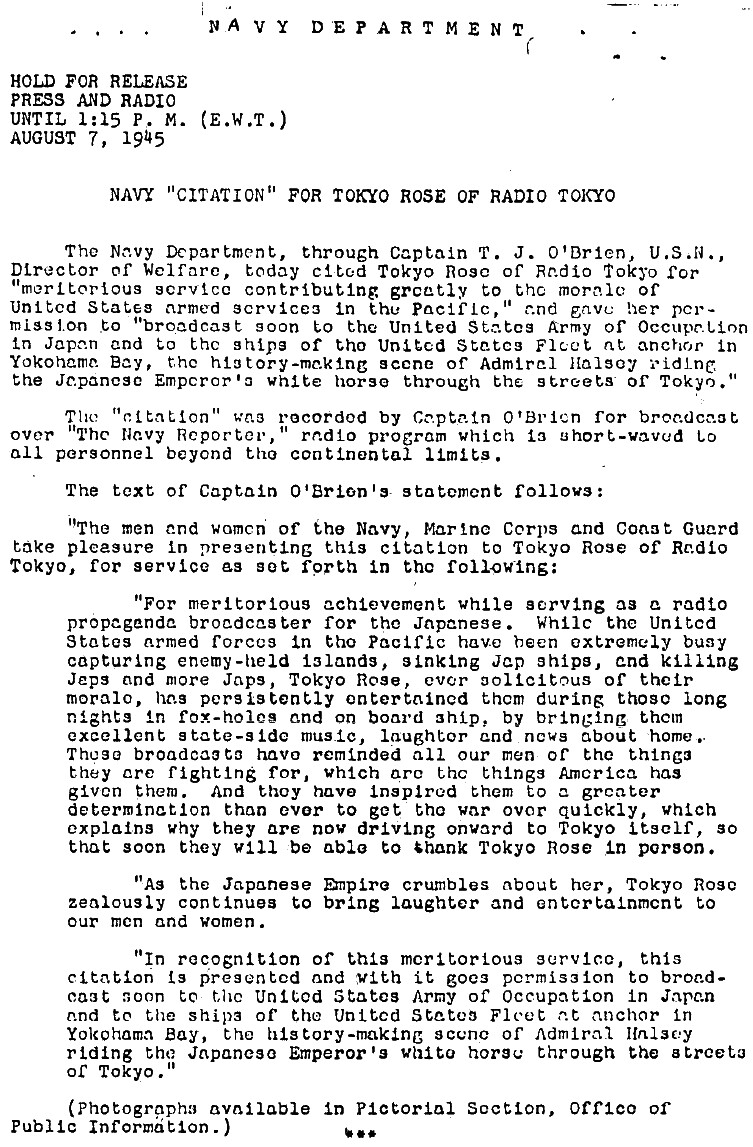

a traitor. The trial of "Tokyo Rose" is well known, and there were

several others who were tried for their anti-American actions. The

whole subject seems to be somewhat a taboo topic -- to many, no doubt,

it is embarassing to talk about their chameleon-like past. You will not

find this data on any other website, and even Wikipedia's page on

Japanese-Americans will not sanction such data to be disseminated.

It is, nevertheless, a historical fact. You will find here an

assortment of news articles and archival material which reveals the

other side of these Nisei who were in Japan during WWII (alphabetical index here). This list is only a fraction of the total.

I have also included below some who were probably not directly

connected with the Japanese military. Further research is being

conducted by author and professor-emeritus Hawaii, John Stephan, who is

hoping to publish his massive work on the Nisei, Call of Ancestry: American Nikkei in

Imperial Japan, 1895-1945; when he does, it will be noted on

this page as the go-to reference book on the Nisei in Japan.

For further info regarding the numbers of Nisei in Japan, here this

from my page on Civilian

Internment Camps in Japan:

Figures do not include

Japanese-Americans (Nisei), who, in accordance with wartime directives

issued by Japan's Ministry of Home Affairs, were to be treated as

Japanese nationals. As for the numbers of Nisei in Japan, "Japanese

figures show that in 1937 there were 50,000 American citizens of

Japanese ancestry residing in Japan" ( Gentlemen of Japan by

Haven, 1944) -- the Japan Foreign Office urged these kibei shimin

(American returnee citizens) to return to the US. Approximately 20,000

Nisei were living in Japan in 1940 ( Zaibei Nihonjinshi, 1940).

According to an estimate by the U.S. Consulate in Yokohama, some 15,000

Nisei were residing in Japan at the end of the war, 10,000 of whom were

eligible to return to the United States ( Rafu Shimpo, March 22,

1947). See Were

We The Enemy? by Rinjiro Sodei for further information. See here

for number of resident aliens of Japanese descent as of June 1942.

Forthcoming book by John J. Stephan will cover this subject in detail.

For further info and extensive data on ethnic Japanese and Japanese

Americans in the US prior to and during WWII, see my EO9066 website, The Preservation of a People, dealing with

the evacuation and relocation of people of Japanese ancestry (assembly

and relocation centers, internment camps, etc.).

From Were we the enemy? American survivors of

Hiroshima by Rinjiro Sodei (1998):

The Japanese

Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimated that the number of Nisei from

both the U.S. mainland and Hawaii who were living in Japan for family

reasons or for education reached almost 30,000 as of January 1929. Of

these, 4,805, or sixteen percent, were living in Hiroshima Prefecture.

Their ages ranged from one to thirty, but 3,803, or some eighty

percent, were attending elementary and middle schools. According to the

same statistics, 11,312 Nisei in the United States, excluding Hawaii,

had parents who came from Hiroshima, while Nisei residing in Hiroshima

numbered 3,404. When 2,759 of the latter group were asked in 1929

whether they wanted to go back to the United States, only 755 answered

yes, while 2,004 said no. In other words, seventy percent expressed no

desire to return.

After the 1924 revision of the Immigration Act

prohibited Japanese from immigrating, only Nisei possessed the right to

enter the country without restriction. A book published in 1929 about

Hiroshima immigrants in the United States emphasized, "From the

viewpoint of the development of the Yamato race overseas ... some

measures must be urgently taken to encourage the Nisei in Japan to come

back to the U.S."

The foreign ministry survey was made that same year,

twelve years before Pearl Harbor. In the intervening years, how many

Nisei returned to the United States? A history of the Japanese in

America, published in December 1940 by the Association of Japanese

Americans in San Francisco, states: "As a result of a nationwide

movement that was started around 1935 to encourage Nisei educated in

Japan to return to the United States as the only real successors to the

Issei, it is estimated that about ten thousand Nisei have returned at

the present time." This statement is qualified, however, by the

observation that "around twenty thousand Nisei are believed to still be

in Japan."

How many of the latter were living in Hiroshima in

1940? No statistics are available, but if we assume that the sixteen

percent of the total that prevailed in 1929 remained consistent, we get

an estimate of around 3,200 for the number of Nisei in Hiroshima. Most

of these would have been living in and near the city of Hiroshima

itself.

The US Consulate estimated there were 15,000 Nisei residing in Japan at

the end of the war, and 10,000 of those were eligible to return to the

US. In May 1946, the GHQ ordered the J-Govt. to produce a list of all

Nisei who lived in Japan during the war, including those who served in

the J-military or in J-govt. Sodei says approx. 5,000 Nisei returned to

the US after the war.

Some thoughts:

What made the difference between pro-Japan and pro-US Nisei? It could

have been the home environment, where the parents were always talking

about their motherland, reading news and literature from or about the

motherland, with very little Americanism being absorbed in their lives,

except perhaps through the American schooling their children were

receiving. These Nisei children would then be receiving mostly news and

views from a Japanese perspective via their parents as well as from the

Japanese language schools (if they were attending) which were teaching

not only the language but also the culture and ethics of Imperial

Japan, all so that they would not forget their heritage. Compounding

this with the fact that many of the Nisei had dual citizenship, it is

no wonder, then, that there would be Nisei with a strong attachment to

Japan, or at least ambivalence. This could be one of the reasons many

in the US military were concerned about the Nisei's loyalties.

Further data:

Up to 7,000

Nisei in Japanese military -- excerpts (PDF) from Michelle Malkin's

book, In Defense of Internment.

18,000

Nisei in Japan in 1933, per Horne book.

From a very enlightening work, The

Pacific Era Has Arrived: Transnational Education among Japanese

Americans, 1932-1941 (PDF), by Eiichiro

Azuma:

The precise number of Nisei

students in Japan during the 1930s is difficult to estimate. According

to some contemporary sources, there were 40,000 to 50,000 American-born

Japanese in the island country in any given year during the decade. The

vast majority of them, however, probably resided in Japan permanently

with their parents, who had returned home for good. Only about 18,000

Nisei were considered "Americans" by the Japanese police, who had kept

a close eye on any "foreign" elements. Still, most of them had spent a

substantial amount of time in Japan, receiving much of their formal

education there rather than in the United States. In 1940, a survey of

Nisei students over eighteen estimated the presence of 1,500 in the

Tokyo area. This is probably the most reliable ballpark figure for the

Nisei youngsters who are the subjects of this study. See Nisei Survey

Committee, The Nisei: A Survey of

Their Educational, Vocational, and Social Problems (Tokyo:

Keisen Girls' School, 1939), 2; and Yuji Ichioka, Beyond National Boundaries: The Complexity

of Japanese-American History, Amerasia Joumal 23 (Winter 1998),

viii. For the general statistics of Nisei in Japan, consult Yamashita

Soen, Nichibei o Tsunagu mono

[Those who link Japan and the United States] (Tokyo: Bunseisha, 1938),

319-334.

See here for more on the 50,000 figure.

See also Chapter 5 re the Nisei in Japan in Japanese Americans and Cultural

Continuity: Maintaining Language through Heritage by

Toyotomi Morimoto.

Nisei_in_Japan_211_G-2_FEC_Jan-Dec_1946.pdf

- List of Nisei employed by the Japanese Govt. and desirous of

repatriation to US. Mention is made of 4,500 Nisei who were granted

Japanese citizenship (possible correlation with number of renunciants

at the relocation centers, viz. Tule Lake). Note also that Japanese

nationality was NOT a pre-requisite; some even were advised not to

acquire Japanese citizenship.

For more information on the Kibei, see this WRA article, Japanese Americans educated in Japan: The

Kibei.

Transnationalism

in education: the backgrounds, motives, and experiences of Nisei

students in Japan before World War 2 by Yuko Konno

Beyond Two Homelands Migration and

Transnationalism of Japanese Americans in the Pacific, 1930-1955

- Enlightening paper by Michael Jin (2013) on the "50,000 American

migrants of Japanese ancestry (Nisei) who traversed across national and

colonial borders in the Pacific before, during, and after World War II.

Among these Japanese American transnational migrants, 10,000-20,000

returned to the United States before the outbreak of Pearl Harbor in

December 1941 and became known as Kibei." A number of Nisei mentioned

by name in this work.

See Densho.org's article, Stranded: Nisei in Japan Before, During,

and After World War II, review of the book Midnight in Broad Daylight by

Pamela Rotner Sakamoto. Densho.org Archives (guest login required) has

a number of interviews relating to Life

in Japan -- During WWII.

Books on this topic - much to be gleaned from these, esp. re the issues

of loyalty and collaboration:

Nisei

in Japan -- interesting excerpt from the Far Eastern Survey, Apr. 19, 1944

See Kabuki's Forgotten War: 1931-1945

by Brandon (2009), p. 390 note: "Ministry of Health and Welfare in

1943... called on Nisei to resist assimilation and 'remain aware of the

superiority of the Japanese people and proud of being a member of the

leading race.'" See also sections dealing with dual nationality Nisei

and their inner conflict (search).

Additional Notes:

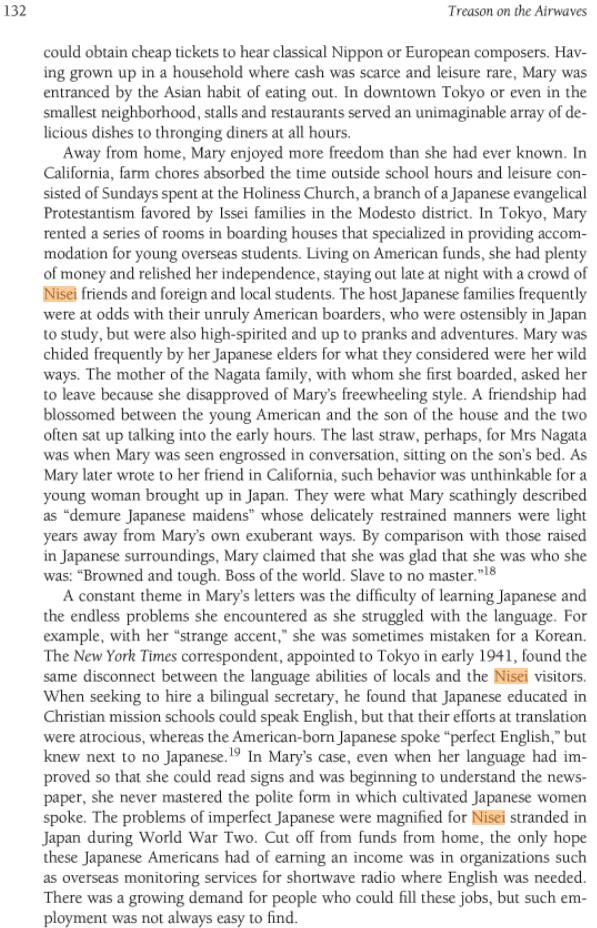

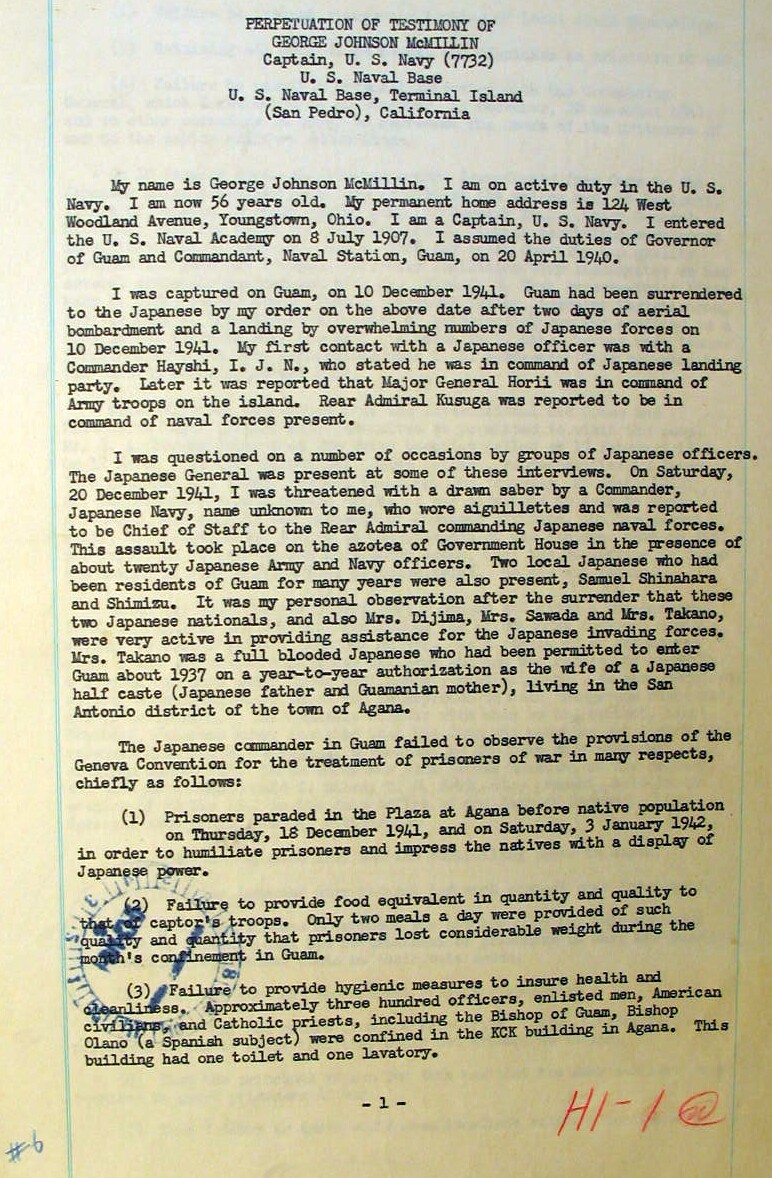

Image: Banquet

for Nisei, Kaigai Doho Taikai (Overseas Compatriots' Convention), Tokyo

1940-11 (image courtesy of John Stephan). Also related organization

Nisei Rengokai (Nisei Union).

"Bushido is the very core of the Nisei" -- Terry Shima, executive

director for the Japanese American Veteran Association

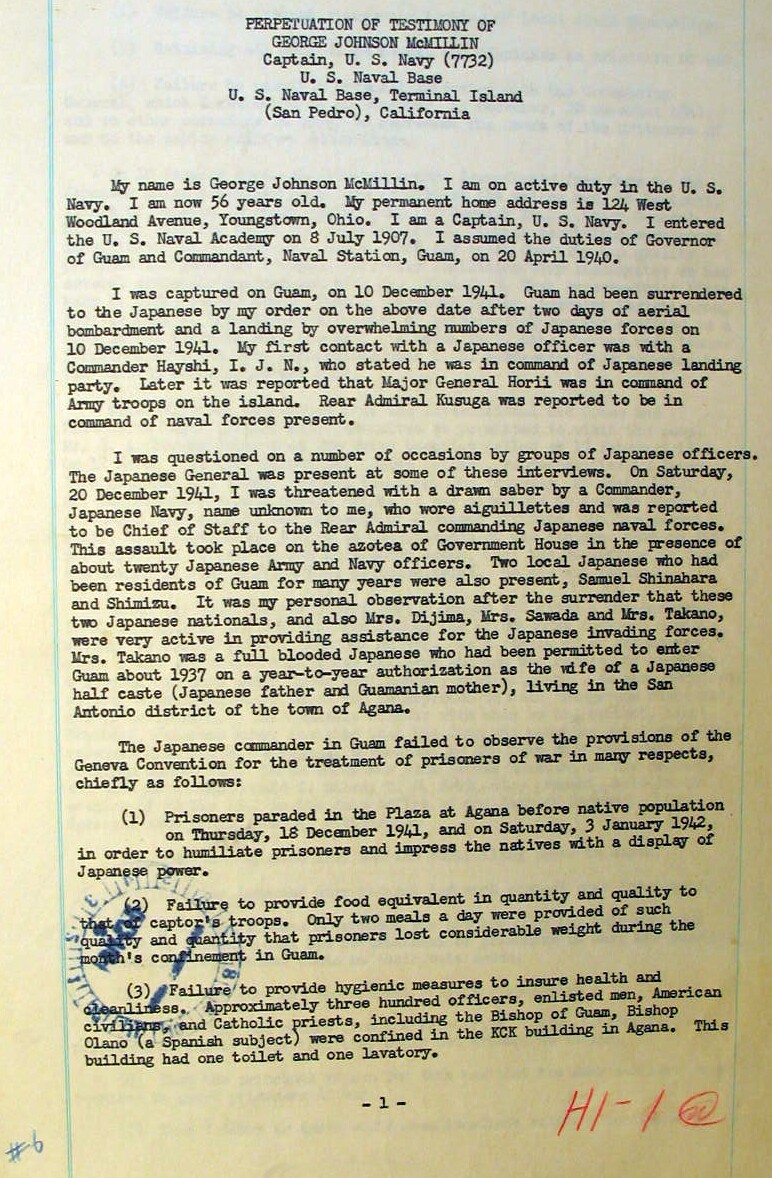

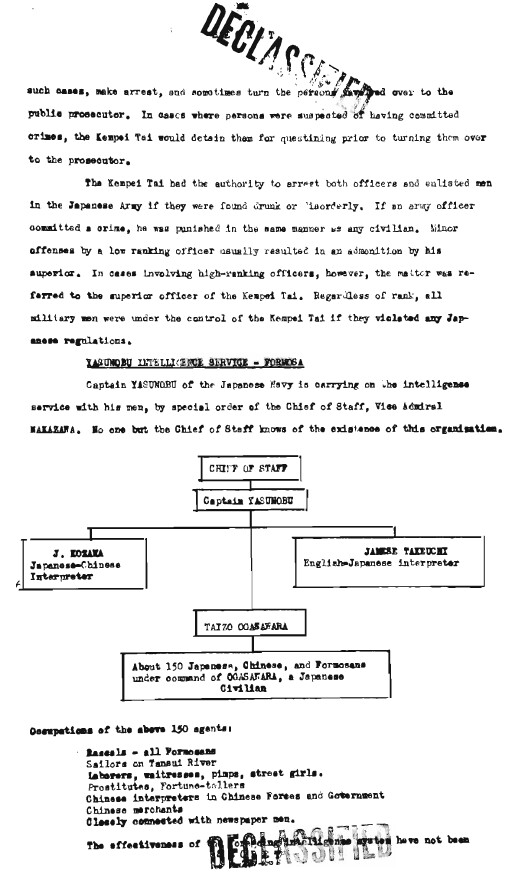

A number of interpreters are mentioned in the Tokyo War Crimes Trials

(IMTFE) Reviews. A search within this file for "interpreter" may give

possible leads to more Nisei involved at the POW camps:

See further Assorted

Notes at end of this page.

Alphabetical

Index of Names

Akune, Saburo and Shiro

Domoto, Kaji

Fujimoto

Fujisawa, Meiji

Fukami, Yasukuni Frank

Fukuhara, Harry

Funatsu, Toshiko

Hamada, George

Harada, Yoshio

Hikita, Toyokazu

Hirano

Honda, Chikaki

Imamura, Shigeo

Inoue, Kanao

Ishio, Jack

Iwatake, Warren

Jibutsu, Fumitane

Kameoka, Masaji

Kanai, Hiroto

Kano, Toshiyuki

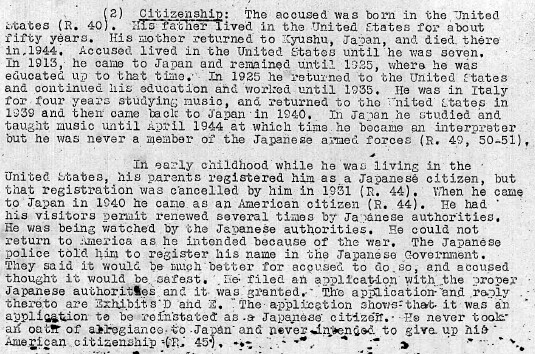

Kawakita, Tomoya

Kido, Shigemi

Kotoshirodo, Richard

|

Matsuda,

Jimmy

Matsumotos

Matsumura, Kan

Miho, Fumiye

Mikami, Yoshie

Miura, Kay Kiyoshi

Morishige, Torao

Murada

(Murata), Hisao?

Muroya, Mary

Nakahara, Jiro

Nakatani, Kunio

Nakayama, Michael

Niimori, Genichiro

Nishi

Nishikawa, Mitsugi

Nishimura, Kay

Noda, Eiichi

Nonin

Okada, Haruo

Okimura, Kiyokura

Onishi

Ozaki, Harley (Toyonishiki)

Ozasa, George |

Sakakida,

Richard

Sako, Sydney

Sano, Iwao Peter

Sasaki, James

Shinohara, Samuel

Suzuki, Jerry

Takamura, Clifton

Takeuchi, James

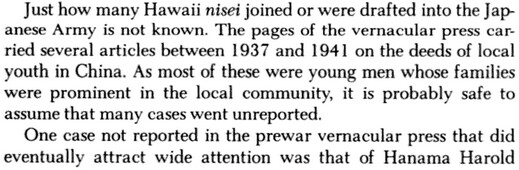

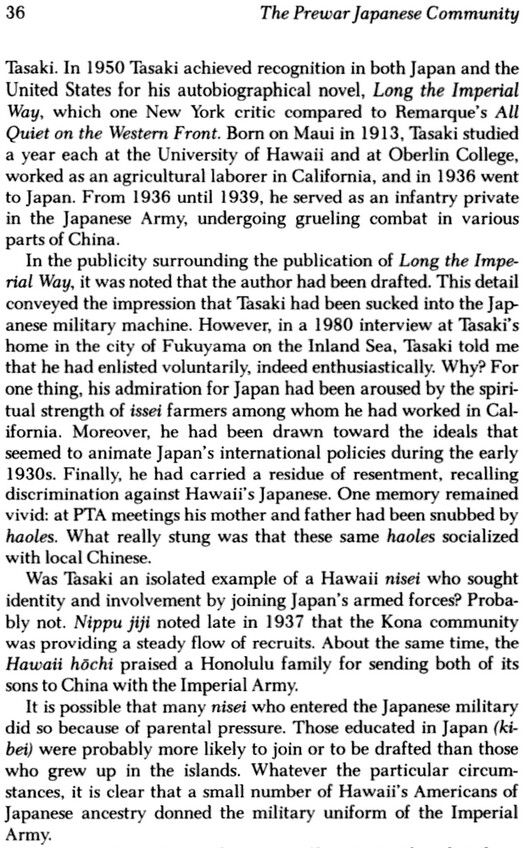

Tasaki,

Hanama Harold

Tateishi, Kei

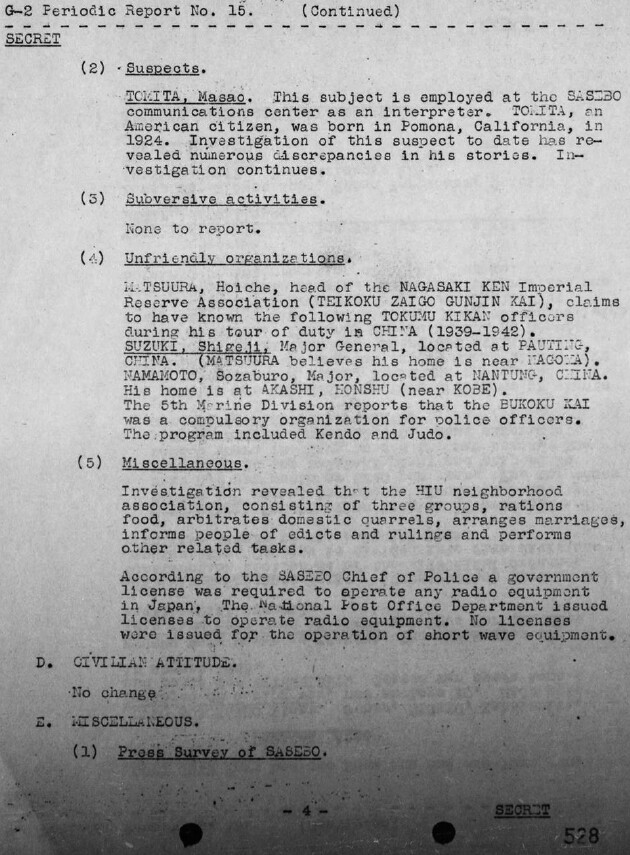

Toguri, Iva

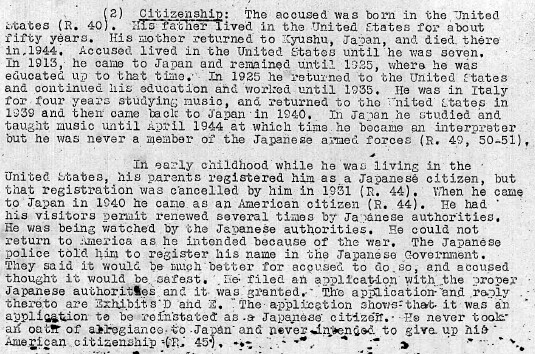

Tomita, Mary

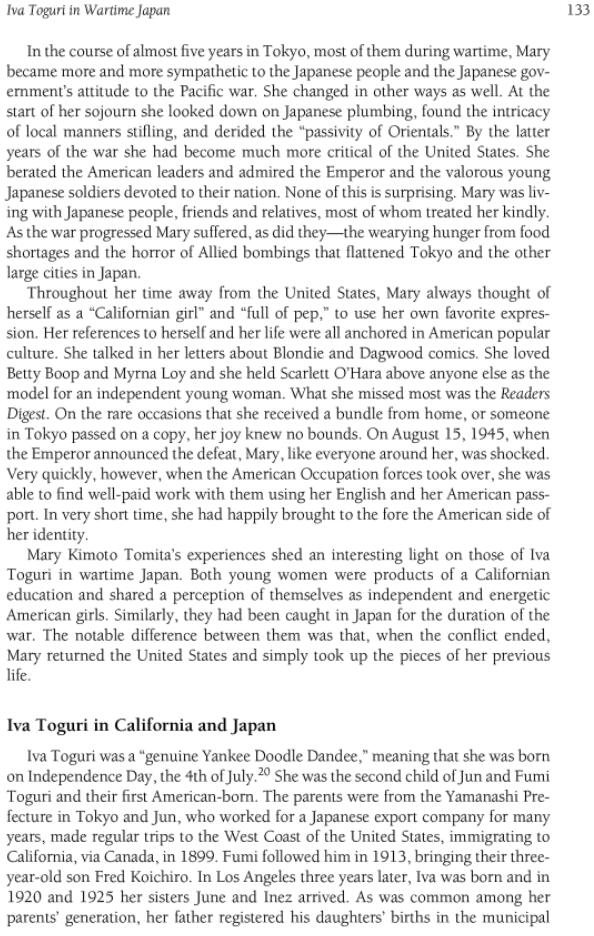

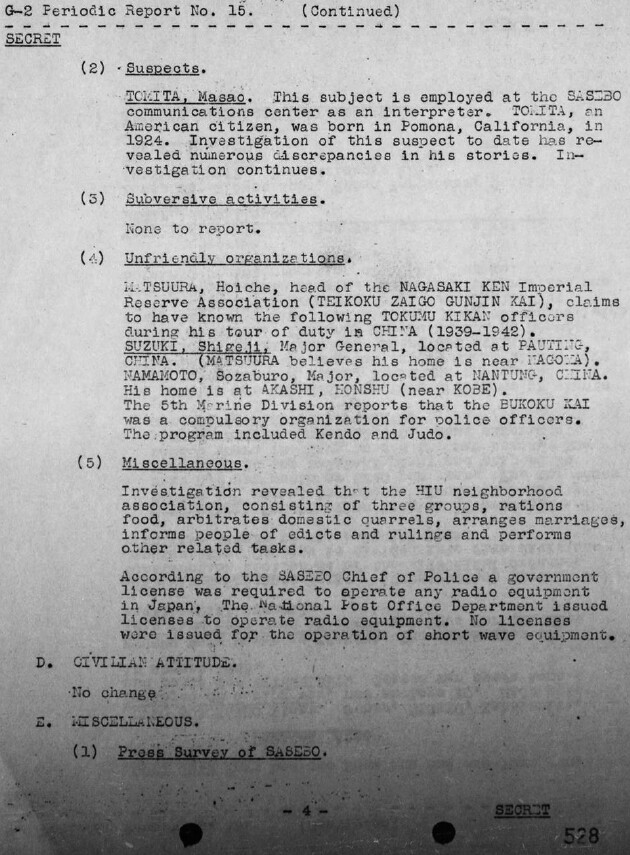

Tomita, Masao

Tsuda, Taihei

Ueno, Harry

Uno, Kazumaro Buddy

Uyeminami, Fred

Wakatake, Clyde

Yamada, Shigeo

Yamanaka, Bob

Yamane, George

Yamashita

Yamauchi, Kunimitsu

Yempuku

(Empuku), Toru, Goro, and Donald

Yoneda, Karl

Yonekura, Mary and Alice

Yoshida, Jim |

Saburo and Shiro Akune

Per article, MIS

Members with Brothers Serving in Japanese Imperial Forces during WWII:

Harry and Ken Akune served in the

MIS and their two brothers, Saburo and Shiro, were drafted into the

Imperial Japanese Navy. After the death of his wife, Ichiro—father of

the Akune boys—took his nine children to settle in his hometown in

Kagoshima Prefecture. Later, before WW II, Harry and Ken were sent to

California to work and send remittances to their family.

Following Japan’s attack of Pearl Harbor, Harry and Ken Akune were

among the 118,000 persons of Japanese ancestry who were placed in

internment camps against their will. “Then, one day an Army recruiter

came with news that the government now wanted young men from the

internment camps to join the military. I didn't care what the

government had done to us," Ken Akune said.

"When they came around, it was a chance for me to do what Americans

were supposed to do, go out and serve their country. When they opened

their door, for me, I felt like my rights were given back to me. I also

thought about if I met my brother out in the field, what would I do?"

Ken Akune said. "You don't want to kill him, but if he points his rifle

at you, what can you do?"

Ken and Harry graduated from the MIS Language School in 1942 and were

deployed to the Asia Pacific war zone, Ken to Burma to work for the

Office of War Information to conduct propaganda against Japan. Harry

was sent to New Guinea and the Philippines to interrogate Japanese

prisoners and to translate documents. Harry, who had not made a

parachute jump before, joined his colleagues of the 503rd Paratroopers

to jump onto Corregidor island. Their brothers in the Japanese Navy,

Saburo was a spotter of American targets for the kamikaze pilots and

Shiro, just 15, served in the training program for recruits at the

Sasebo Naval Base.

After the war, Harry and Ken, while serving in the demobilization of

Japanese armed forces, visited their family in Kagoshima Prefecture.

The four brothers, two on each side, got into a heated argument as to

which side, Japan or America, was right. The confrontation was stopped

by their father, who reminded them the war was over.

Saburo and Shiro returned to live in America, where, ironically, Shiro

was drafted and fought in the Korean War.

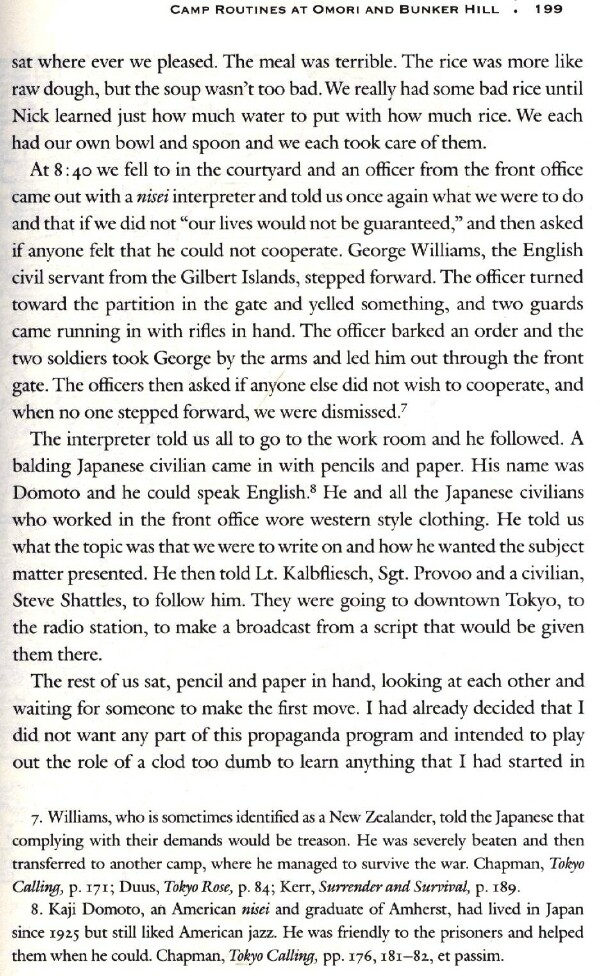

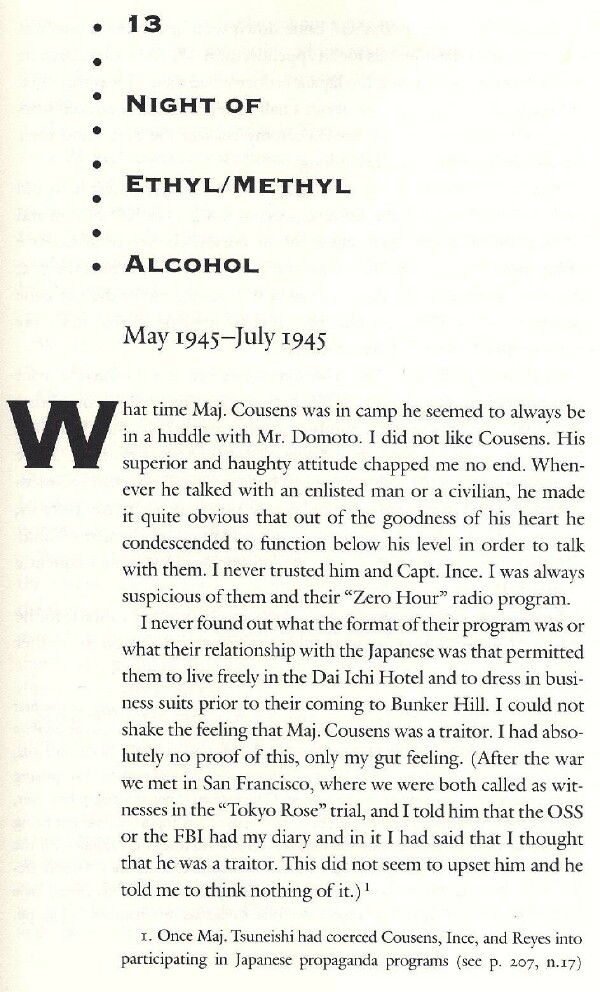

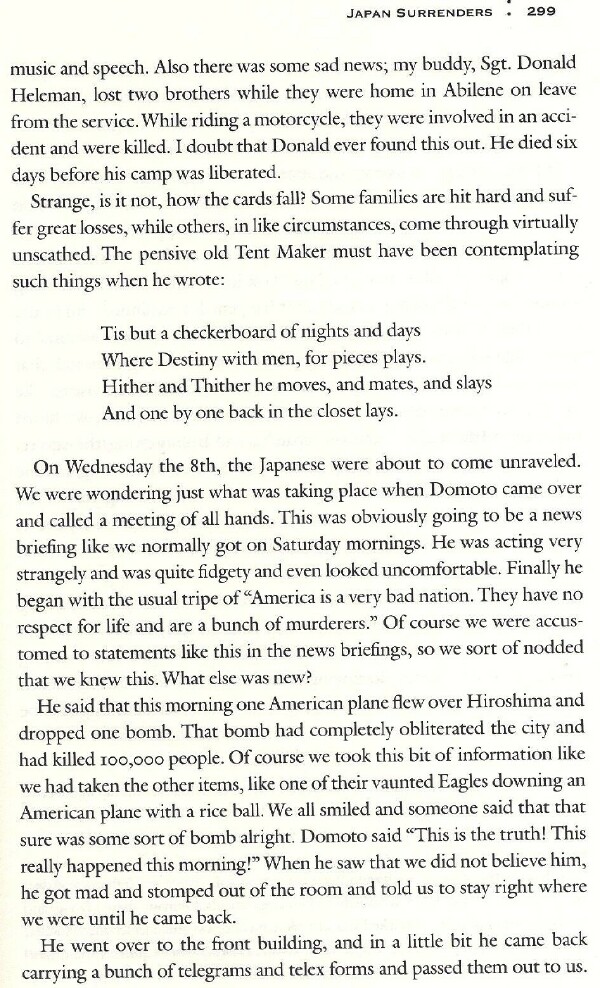

Kaji Domoto

From Foo

Fujita's book:

From Kaji Domoto - Nisei at Omori camp - US News Hiroshima.html:

"The news came much quicker to

Sgt. Frank Fujita, a Japanese-American held eight blocks from the

Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Kaji Domoto, a U.S.-born Japanese who liked

to serve up anti-American diatribes, told the assembled POWs that the

"murderers" had destroyed an entire city with one bomb. The GIs

scoffed. Domoto was notorious for fanciful tales, including one about a

U.S. plane downed by a rice ball. He convinced them this time by

producing Western dispatches on Truman's announcement."

Domoto

at Bunka camp with Cousens 1946-09-27.pdf - Sydney Morning Herald

article: "Cousens said Domoto had been instrumental in saving the lives

of three officers."

Fujimoto

See Otten

testimony, Nagoya POW Camp #10: "Civilian Interpreter Fujimoto

(Thug) strafed [punished] POW's, was American born and educated." He

was at the Osaka Chikko POW Camp first, according to this

site.

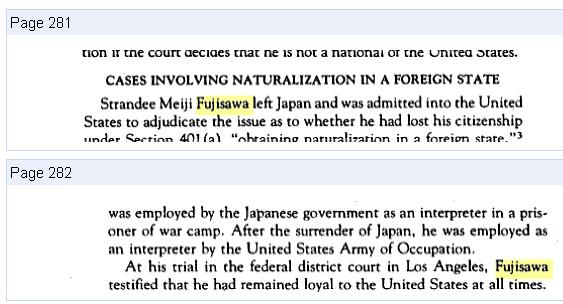

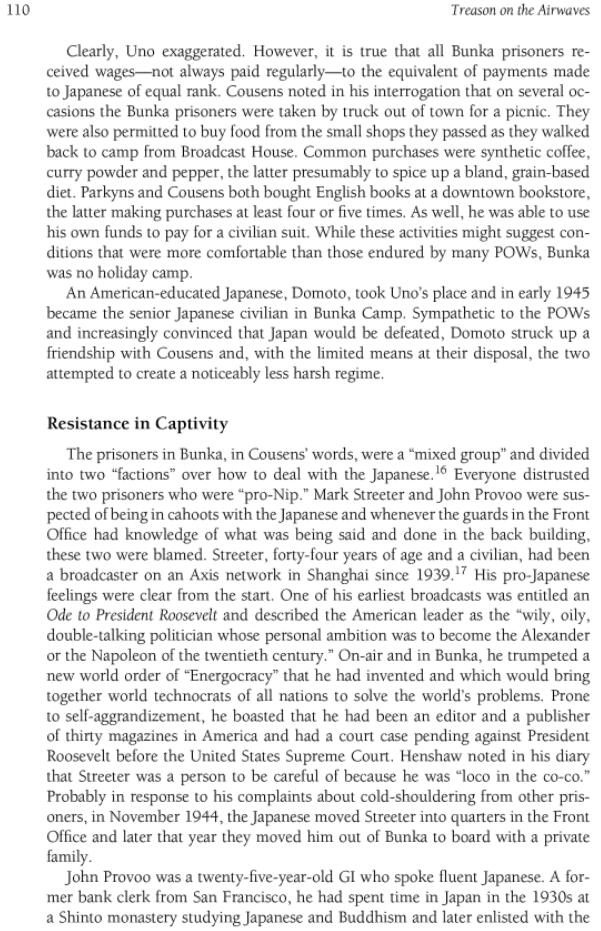

Meiji Fujisawa

Oeyama POW camp interpreter (From Bamboo People by Chuman):

Lengthy chapter here about Kawakita (Chapter Four) in which Fujisawa

(Fujizawa) is mentioned, Kawakita's childhood friend:

America's

Geisha Ally by Naoko Shibusawa, 2006

Yasukuni "Frank" Fukami

Per Statement

of Sachio Egawa (from bottom of page 26) of Fukuoka POW Camp #18

(Sasebo):

"About March or April [1943]... a

seamen name FUKAMI, Yasukuni came to our camp. FUKAMI used to say that

he was born in AMERICA [San Francisco, 1915] and indeed, excelled in

speaking English. However, he was of an ugly temperament, and he often

hit the young service personnel and workers. In spite of his behavior,

he was liked by the superior, SAMEJIMA, and SAMEJIMA once used him to

obtain blankets and towels from the prisoners against their will... I

reported the matter to a superior named TAKAHASHI... [who] made FUKAMI

return the articles to the prisoners... I heard of FUKAMI committing a

great deal of outrages against the prisoners... WATANABE [Navy unit

commander] learned of FUKAMI's acts and wildness and had him

transferred about July or August."

Harry Fukuhara, brothers of

(Frank, Pierce, Victor)

Second Lt. Harry Fukuhara left his native Seattle as a teen when his

mother took him and his siblings to her hometown of Hiroshima following

his father’s death in 1933. He returned to the United States for

college; his three brothers remained in Japan. He served in the US

Army; they served in the Japanese Army. His mother and oldest brother

suffered radiation sickness, with his brother dying before the end of

1945. “‘Futatsu no sokoku’ hazama ni ikite” [Living Between ‘Two

Fatherlands,’], Tokyo Shimbun, 11 June 1996, p. 28.

From Nisei Linguists review:

Toshikawa Takao, “Nikkei nisei,

Beigun joho shoko ga hajimete shogen shita: ‘Futatsu no sokoku’

rimenshi,” [“Nisei, U.S. Military Officer Testifies for First Time: The

Inside Story of ‘Two Fatherlands’”], Shukan

Posuto, 3 March 1995: 219. Many Japanese histories, memoirs, and

media reports tell the stories of Nisei in service to one country or

the other. One history of Japanese Americans is Kikuchi Yuki’s Hawai Nikkei nisei no Taieheiyo Senso

[The Pacific War of Hawaiian Nisei] (Tokyo: Sanichi Shobo, 1995). A

story of Japanese Americans on the other side is Tachibana Yuzuru’s Teikoku Kaigun shikan ni natta Nikkei Nisei

[The Nisei Who Became an Officer of the Imperial Navy] (Tokyo: Tsukiji

Shokan, 1994). As Nisei who were living in the United States at the

start of the war joined the US military and intelligence organs, so

many of those in Japan at that time served as linguists in the IJA and

IJN, the Foreign Ministry, and the official Domei News Agency which,

like the BBC, monitored foreign media broadcasts.

--------------------

U.S. Officer Feared Worst For

Family Living in Japan / Brothers split by war and circumstance

August 05,

1995

By Tara Shioya, Chronicle Staff Writer

In the summer of 1945, U.S. Army

Lieutenant Harry Fukuhara was assigned to the Philippine island

of Luzon as a linguist with the 33rd Infantry Division. The end of the

war was near, and Allied forces were preparing to invade Japan.

Fukuhara's unit would head the invasion.

And for the first time since he

joined the Army, Fukuhara thought of what that could mean for his

family in Japan.

Before the war, his mother and his

three brothers had returned to Hiroshima from the United States, where

Fukuhara was born. He had not heard from them in four years, since the

war broke out. When the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, on August

6, Fukuhara assumed the worst. There were no survivors, he was told. In

Hiroshima, nothing would live for the next 100 years. Still, he knew he

had to go see for himself.

He was not expecting what he found.

"I thought I should go to Japan and

at least see if I could find them," recalls Fukuhara, now 75, a retired

Army colonel who lives in San Jose. "But I figured there was no chance

that they would have survived."

He arrived in Japan a month later,

having been reassigned to the American occupation forces in Kobe. With

the Army's permission, he and a driver set out for Hiroshima in a jeep

one morning before dawn.

They drove all day and night, using

train trestles to cross rivers where bridges had been destroyed. The

next morning they reached Takasu-machi, the Hiroshima suburb where

Fukuhara's family lived. The houses appeared to be intact, but on the

streets there were no people. Through the neighborhood, the usual

early- morning murmur of waking families, children's squeals, chickens

in the back yard -- the sounds of life -- were not to be heard.

The Fukuhara home was among those

standing. A row of shrubs had been charred, their silhouettes

superimposed on the back wall of the house, which faced the center of

the city. Inside the two-story house, daggers of glass jutted from the

walls -- the windows and doors were gone. Fukuhara stood in the hallway

and called out "moshi moshi" ("hello, hello"). But there was no reply.

As he surveyed the damage, his

mother appeared.

"I was pretty surprised," remembers

Fukuhara, a quiet man who seems to yield to his emotions only

reluctantly. "We just stood there looking at each other."

His mother and her sister had

survived the bomb by hiding in an underground shelter. At the time of

the blast, his mother was rinsing her feet outside the house. Her

oldest son, Victor, 32, had

been less fortunate. When the bomb hit, he was on his way to work at a

factory in Hiroshima. The radiation had left him scarcely able to talk

or eat. The day after the bomb, relatives had found him wandering

through town, dazed and with his shirt burned to rags, and had brought

him home.

At first, Fukuhara's mother did not

recognize her American son. His complexion had turned sallow from

medication he was taking for malaria. She had not seen him since 1938

and was confused by the U.S. Army uniform.

After her husband's death in 1933,

Kinu Fukuhara had left Washington state -- the family's home for more

than 20 years -- and returned to her hometown of Hiroshima with four of

her children. But Harry had come back to the United States soon after

graduating from high school and had gone to California, following a

sister. In the intervening years, the family wrote letters. But then,

after Pearl Harbor, the letters stopped.

Now, from his mother and aunt, he

learned that his other two brothers had also survived. They had not

been in Hiroshima at the time of the bombing but on the southern island

of Kyushu, preparing for what was expected to be imminent invasion by

American troops.

Fukuhara learned several months

later that while he was studying aerial attack-plan photographs of the

island, his youngest brother, Frank,

was digging foxholes for the Japanese army in the Kyushu mountains in

expectation of the U.S. landing.

"That was pretty ironic," said

Frank Fukuhara, from his home in Komaki, Japan. "We could have met up

face to face, fighting against each other."

Now 71, he laughs as he recalls his

army training -- learning to crawl on his stomach with a dummy bomb

strapped to his back, to slip beneath the American tanks.

During most of the war, he says, he

had avoided military service by enrolling in an engineering college.

Eventually he was drafted, in April 1945, and was assigned to the

Western Second Battalion Infantry and sent to Kyushu, like the fourth

brother, Pierce.

By the time Harry returned to

Japan, Frank and Pierce had gone back to Hiroshima to work as

interpreters for U.S. forces just outside the city.

"When Harry showed up, I was really

shocked," said Frank Fukuhara. "I thought that he was a prisoner of

war, and that he had been sent back to Japan."

After several hours, he understood

that his brother was in fact a U.S. Army officer and that the tall,

blond soldier who accompanied them on the jeep ride home was not

holding Harry prisoner.

The last Frank had heard, Harry was

working as a houseboy in Glendale, Calif. He had heard nothing of the

Japanese American evacuation and the internment camps. He had no idea

that Harry and their sister, Mary, and her 2- year-old daughter were

relocated to a camp at Gila River, Ariz., and that Harry had

volunteered to join the Army -- or that circumstance had placed them on

opposite sides of the war.

For Frank, who had always hoped to

return to the United States, the choice between "American" and

"Japanese" had been made for him when he was drafted into the Japanese

Imperial Army. But for Harry, that decision was a conscious one.

"I felt I had to make up my mind to

stay as an American," he says of his decision to volunteer. "I had no

feeling of loyalty to Japan."

Today, Harry Fukuhara still spends

considerable time thinking about the war, as president of the Northern

California Military Intelligence Service (MIS) -- a 400-member

association of Japanese Americans who served in the war in the Pacific.

He says he still believes that

dropping the A-bomb shortened the war and ultimately saved lives,

despite the price his family paid. His brother Victor died of radiation

sickness in 1947. His mother died of similar causes in 1968.

Frank Fukuhara is unable to say

whether he believes that use of the bomb was justified, especially when

he thinks of their 13-year-old cousin Kimiko. On Aug. 6, 1945, she had

just finished her wartime work duties at school and was on the roof of

the building when the bomb struck. Blinded by the flash and badly

burned, she crawled half a mile to a temporary hospital. Minutes after

her mother found her, she died.

"I thought the atomic bomb was

really miserable," Frank Fukuhara says, his voice faltering for a

moment. "But it ended the war. It could have lasted much longer."

But the memory of Hiroshima is

painful for both brothers.

Despite Harry Fukuhara's apparent

pragmatism about the bomb, it was not until 1989 that he returned again

to Hiroshima.

"I guess I wanted to avoid going

there," he says. "I didn't even want to think about it. There was

nothing positive about the time I was there in 1945."

See also this review

of book on Fukuharas, "Midnight in Broad Daylight," by Pamela

Rotner Sakamoto. The Japan Times had this article, The unbelievable true story of a Japanese

family that went to war with itself.

From essay by Fukuhara, Military

Occupation of Japan (WWW.NJAVC.ORG):

About two weeks after arriving in

Japan, I was able to get permission from my division commander to

travel by Jeep to Hiroshima to look for my family. I arrived in early

October and found my mother and brothers in our partially-damaged

family home on the outskirts of Hiroshima City. My mother had survived

the atomic bomb because she had been in a bomb shelter, but my older

brother Victor had been

injured by the bombing. He was to die a few months later from radiation

poisoning. Many of my relatives had died or disappeared in the atomic

blast.

I was overjoyed to see my two younger brothers, Pierce and Frank. They had been

drafted into the Japanese Army, and had returned home just a few days

before I arrived in Hiroshima. Frank

had been assigned to a suicide unit in Miyazaki Prefecture. He had

been training to blow up a U.S.

military vehicle by running up to it and detonating an explosive strapped to his back. I

shuddered when I heard that he was supposed to guard the beaches of

Miyazaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu. That was where my division

had been planning to land on November 1, 1945. I was glad that the

atomic bomb had ended the war.

.....When I was first assigned to the Toyama CIC office, in September

1947, I met a young Nisei girl who became my wife two years later. Terry Yamamoto had come to Japan as

a teenager before the war. She was working as an interpreter at the

Toyama Military Government Team.

Japanese book:

日

本軍兵士になったアメリカ人たち: 母国と戦った日系二世

Duality of Patriotism: The

untold story of Japanese Americans serving in the Japanese Imperial

Forces during WWII

by Hiroshi Kadoike (2010/02)

Americans who became soldiers of

Japanese military - Nisei who fought against their motherland

From Chapter 2:

Frank Fukuhara - brother

in US Army 二つの母国 (Two Motherlands)

Toshiko Funatsu

Per Stephan, possibly worked as a communications monitor for the

Imperial Army or Navy. After war was English instructor in Yahata,

Kyushu (PDF).

George Hamada

Nisei? interpreter at Zentsuji POW Camp (photo). Affidavit

by POW Nelson says that Hamada lived in the US for 20 years. Photo

shows "Bibb County, Georgia" location.

Yoshio Harada

On island of Niihau, helped Japanese pilot who crashed there during

attack on Pearl Harbor. See Robar

p. 340 and Malkin

p. 2+, photo on p. 289.

From Wiener

testimony:

b. Another Nisei, Harada, committed

treason against the United States within the constitutional definition

(Art. III, § 3) of "adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and

Comfort." A Japanese warplane, damaged during the Pearl Harbor attack,

landed on the small Hawaiian island of Niihau. Local Hawaiians took

away the pilot's pistol and his papers, but Harada supplied him with

other arms belonging to Harada's employer, after which, for six

days, the pilot and Harada terrorized the entire island. Then a

Hawaiian who had been shot by the pilot managed to kill him, after

which Harada committed suicide. S. Conn, Guarding the United

States and Its Outposts, p. 194

[hereafter "Conn, Guarding"];

W. Lord, Day of Infamy, pp. 195-200; J.J.

Stephan, Hawaii Under the Rising Sun,

p. 168.

The Commission relegates this incident to a footnote (Rep. 430-431,

n.14), does not recognize that Harada's acts constituted treason,

and therefore fails to recognize that, flatly contrary to its own

blanket assertion, Harada, like Kawakita and Tokyo Rose, was indeed an

"individual American citizen... actively disloyal to his country."

Toyokazu Hikita

Born in Vancouver, BC, 1922. Went to Japan in 1939 and drafted into

J-Army in 1943, then transferred to Tokyo Kempeitai. See p. 5 of this

doc:

Yokohama

Trial

Dockets No. T294 HIKITA

Hirano

In this article (More_Jap_Atrocities_KingsportTimes_1944-1-30.pdf),

note on page 2 under "Demands Action," there is mention of a Lieut.

Hirano, "a young Japanese from the United States, who was

responsible for the horrible prison conditions existing there" at the

Shanghai Bridge House jail. This could be the same person as Cmdr.

Smith mentioned in his

statement:

"There was one Kato there [at

Bridge House, Shanghai], an interpreter, who was very vicious. One of

the worst of all was a Japanese interpreter who designated himself as

being No. 56, he being very careful to keep us from learning his name.

No. 56 was this man's official number as an interpreter. I have his

name and something of his personal history safely secured in Shanghai

and full information can be obtained about him after the war. This man

had spent at least half of each year in the states for a long period as

he was in the export business from Japan. Although being a Japanese

subject, he was married to an American Japanese and had several

children. Two of his daughters at that time were attending the

University of Southern California. All of his family except himself

were American citizens. He was one of the vilest, most vicious men in

the whole place. This man was cautious in handling us military

prisoners and evinced strong wishes to remain incognito."

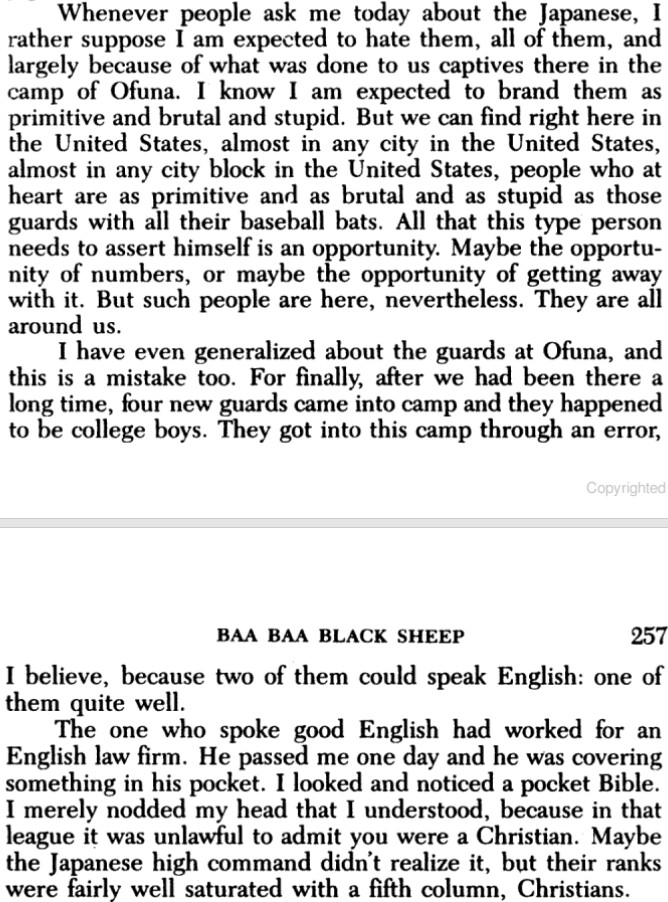

Chikaki Honda ("Eddie")

Born in Hawaii, went to Japan in 1929, renounced US citizenship in

1941, worked with other Nisei in Civilian Intelligence Corps, gave

talks at Nisei Rengokai in Tokyo, became interrogator on Rabaul whom

Boyington had met. From Black Sheep One: The Life of Gregory Pappy

Boyington by Gamble):

Shigeo Imamura

Born in San Jose, CA, went to Japan when 10 years old, later becoming a

kamikaze pilot. Wrote book, SHIG

-- The True Story of An American Kamikaze: A Memoir.

Kanao Inouye ("Kamloops Kid")

Canadian Nisei (see Wikipedia

entry) -- was at Shamshuipo prison camp, and interpreter for

Kempeitai military police in Hong Kong. Mentioned in Roland's Long

Night's Journey Into Day, pp315-316. Mentioned in The Damned by Greenfield.

Mentioned also in Prisoner of the Turnip Heads: The Fall of

Hong Kong and the Imprisionment by the Japanese by

Wright-Nooth (2000).

See also trial case:

Jack Ishio

From Tacoma, WA; was registered as a dual-citizen. Served as an

anti-aircraft gunner in the Japanese army, shooting down American dive

bombers. Was a mile from Hiroshima when A-bomb was dropped. Helped

cremate the dead over the next two weeks. Quoted in

this article as saying, "It was dreadful. But I never felt a sense

of anger at the U.S. that they used such a weapon to bring the war to

an end. I think that was the right

thing to do."

Nobuaki Warren Iwatake

From Wikipedia:

Nobuaki "Warren" Iwatake (1923-)

was Radio Operator and communications intercepter and a veteran of the

World War veteran of the World War 2 Imperial Japanese Army.

Family history

He was born in Kahului, Hawaii, USA. Warren was the eldest son of six

children and was raised in Kahului. The father of Iwatake, a Kobayashi

store employee, presumed drowned from a fishing trip at Peahi. With the

loss of the family breadwinner, his mother, four brothers, and one

sister moved to Hiroshima, Japan, to live with an uncle in November,

1940. Warren stayed on Maui to graduate with his Maui High School class

of '41, and then left to rejoin his family in Hiroshima. The December

7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor would eventually have a

profound effect on Iwatake's family, and lead to an unlikely

association with George Herbert Walker Bush, the 41st President of the

United States.

Service in Imperial Japanese Army

Iwatake was beaten and drafted against his will to the Imperial

Japanese Army from a Japanese college in 1943. He was present when

former United States President George H.W. Bush was shot down over the

Pacific in his Avenger bomber, during September 1944, and was later

rescued by a submarine. Two American crewman with Bush were killed.

Iwatake had missed the battle of Iwo Jima due to an American submarine

attack on his ship's convoy, and was then placed on Chichi-jima, 150

miles north of Iwo Jima. American forces bombed Chichi-jima to cut

radio communications between islands. Former President George H.W.

Bush's task was to bomb the island's communication towers, and possibly

any Imperial Japanese forces. Due to the "island hopping" strategy by

American forces, the island was spared an invasion attack.

Iwatake was present when Japanese Imperial forces captured an American

pilot from Texas by the name of Warren Earl Vaughn. Mr. Iwatake was

assigned to guard and work with Warren Earl Vaughn on Chichi Jima. He

and Warren Earl spent many hours talking and developed a personal

relationship. According to Iwatake, one evening after a bath, the two

were walking back when Iwatake fell into a bomb pit. "It was pitch

black and I couldn't get out. He reached to me and said take his hand"

and Warren Earl pulled Iwatake out. Shortly after the fall of Iwo Jima

in March 1945, the pilot was taken away by other Japanese Naval

Officers and executed at the harbor by beheading. On that day Mr.

Iwatake adopted and kept the name "Warren" in honor and remembrance of

his American friend Warren Earl Vaughn. The story of Warren Earl

Vaughn, Iwatake's observation of the rescue of George H.W. Bush, and

the experiences of other American "Flyboys" is recounted in the book

Flyboys: A True Story of Courage by James Bradley. Warren Iwatake and

President George H.W. Bush met on Chichi Jima in 2002 in a symbolic

reunion of veterans from both sides of the conflict.

Iwatake lost his youngest brother in the Hiroshima atomic bomb attack.

The youngest brother was 500 yards from the epicenter attending a

school. Reportedly, the only thing left was a US Army canteen, as the

youngest brother was vaporized in the atomic attack. Iwatake's uncle,

Dr. Hiroshi Iwatake, was badly burned in the atomic explosion, but

regained his health and lived into the 1980s. Dr. Hiroshi Iwatake's

true story is recounted in the 1966 (1969 Kodansha English translation

by John Bester) historical novel "Black Rain" by Masuji Ibuse. This

title is not to be confused with the 1989 Michael Douglas movie of the

same name, also set in Japan. The Ibuse "Black Rain", though centered

around fictional characters, is based on interviews with actual atom

bomb survivors, including Hiroshi Iwatake. Graphic details in the

novel, such as the maggots eating away at Hiroshi's earlobe, are true.

The nephew in the novel is Warren Iwatake's youngest brother Takashi.

The novel states that Takashi's metal ID tag was found. However,

Warren's brother Masaru reported that all he could find when he

searched for Takashi amongst the ruins of Hiroshima was Takashi's U.S.

Army canteen.

After the war, Iwatake served as a translator for the American Embassy

in Tokyo for 35 years.

And this article:

By CAPT. NEIL F. MURPHY

Marine Corps Public Affairs Office

CAMP S.D. BUTLER, Okinawa,

Japan - On Feb. 23, 1945, on the tiny coral island of Chichi Shima,

jutting out of the Bonin Islands east of Okinawa and north of Iwo Jima,

anti-aircraft fire ripped through the sky.

A Marine Corps F-4U Corsair

fighter, on an air-raid mission from the USS Bennington, lumbered over

the island and slammed into the ocean after being shredded by the wall

of lead.

Slowly descending in his

parachute to the ocean, the pilot, 23-year-old Childress native 2nd Lt

Warren Earl Vaughn, watched helplessly as his co-pilot sank silently

into the ocean.

Hitting the water and

swimming through shark-infested coral to the surf, Vaughn was snatched

from the shore by defending Japanese soldiers and sailors and dragged

into their camp.

Vaughn had not been the

first to be shot down near this island. Five months before, future

President George Bush, a naval aviator aboard the USS San Jacinto, also

was shot down in his Avenger aircraft off this dreaded coastline. But

Bush was rescued by the submarine USS Finback, narrowly avoiding the

fate that awaited Vaughn.

Now a prisoner of war on

desolate Chichi Shima, Vaughn was forced to work in a sweltering

communications hut high atop Mount Yoake, routinely monitoring his own

forces' radio communications along with a young Japanese army private.

Private Nobuaki Iwatake, now

76, also was stranded on the island after the freighter ship he and

other Japanese soldiers were traveling on months before, the Nissho

Maru, was torpedoed miles off the coast.

Iwatake, an unwilling

Japanese conscript with dual U.S.-Japanese citizenship, was forced to

join the Imperial Japanese Army because of his English skills.

Having attended Maui High

School in Hawaii, he was a student at Mejii University in Tokyo when

the war broke out. Two years after being drafted, Iwatake found himself

on Chichi Shima monitoring U.S. radio transmissions and working with a

fellow U.S. citizen who was labeled his enemy.

Meanwhile, the battle for

Iwo Jima raged on just south of the island. As Americans and Japanese

bled and died at each others' hands on the hot, black sands, Vaughn and

Iwatake began to share a friendship that has remained in Iwatake's mind

and heart to this day.

"Warren was a great man,"

Iwatake said. "Even as a prisoner, he had a sense of humor and often

told us jokes and had a good, healthy spirit.

"I remember him being

brought into our camp with his green flight suit on months after I had

seen (George) Bush shot down and rescued by the U.S. Navy. Warren

wasn't as lucky. Warren was tall and handsome and had a real Texas

accent.

"I always wonder if he had

been rescued, what would have become of him and what great things he

would have done for his country, like Bush.

"One night, Warren was

talking with some kamikaze pilots who had come into our hut, and they

asked what he would do if they got on his tail. Warren stood up,

towering over them and using his hands to depict flying aircraft, he

explained how he would roll up and loop to get behind them and shoot

them down. Impressed by his skill, they shook his hand and wished him

luck as they departed."

Another time, while the two

were in their hut working, their area was hit by bombs dropped by U.S.

P-51 Mustangs that were attacking the island.

"They had no idea Warren was

there, and he was very upset that they dropped bombs on him. He ran out

and yelled at them as they flew past, shaking his hands and cursing,"

Iwatake said.

Late one evening, Iwatake

even smuggled Vaughn into a Japanese-style bathhouse on the island, so

he could clean himself up. On the way to the facility, the nearsighted

Iwatake fell into a bomb crater, which offered Vaughn a chance to

escape. Instead, Vaughn reached down into the six-foot pit and helped

his friend out to safety.

"That's the way he was,"

Iwatake said.

While monitoring the nightly

radio transmissions from Iwo Jima, Vaughn and Iwatake continued to

trade stories of their lives and what they would do once the war ended.

The two even had begun to plan an escape from the island, but as fate

would have it, time ran out.

One morning in early March,

Vaughn intercepted a message that stated, "All organized Japanese

resistance has ended. The U.S. Marines have taken Iwo Jima."

He hesitantly passed the

transmission to Iwatake, who translated it and forwarded it to his

chain of command.

The morning after learning

of the fall of Iwo Jima and the impending Japanese defeat, an irate

Japanese Imperial Navy officer-in-charge of the communications unit on

Mount Yoake, Capt. Yoshii, came into the hut. He removed Vaughn from

his work area and collected seven other prisoners of war who also were

shot down over the island.

Iwatake said Vaughn looked

at him and replied, ' "They're taking me away. Goodbye and take care,

my friend.' "

Vaughn was led down the

mountain.

"I will never forget that

sad look on his face as he left," Iwatake said.

That afternoon, in a

horrific display of inhumanity, Yoshii and some of his men bayoneted

and beheaded the prisoners by the seashore.

Months later, according to

"The History of Marine Corps Aviation," Yoshii and many others were

tried and hanged in Saipan for war crimes against Vaughn and the

others.

"I found out the day after

it happened. I was shocked, shaken and deeply saddened. They had killed

my friend, Warren, and for what, I couldn't understand why," Iwatake

said. "I hated Yoshii for that."

More than half a century

later, the friendship that ended in such dismay still lives today in

the mind of that unwilling Japanese conscript. Iwatake is still

searching for final closure to the events leading up to Vaughn's death.

Recently, Iwatake expressed

his desire to meet any of Vaughn's remaining family members to help

heal the wounds and share the memories of his last days alive.

"Some of the men who

witnessed the execution said he was very brave, and that was just like

him. I want people to remember Warren," Iwatake said. "After the war, I

changed my given name (to Warren) in remembrance of my friend. He lives

in my memory forever.

"I vowed that if I ever

survived that war, Warren Iwatake would do something to contribute to

U.S.-Japan relations in some way."

Iwatake recently retired

after 25 years of working in the press section of the U.S. Embassy in

Tokyo. While there, he often searched for Vaughn's family, and every

time it produced nothing.

"Time is running out, and I

want to see his family so bad," Iwatake said.

Vaughn is currently listed

as a POW, killed in action, as of March 5, 1945, and his body never was

recovered from the island.

His last known listed

relative was his mother, Evia McDonald, from Childress.

Born in Childress on Sept.

20, 1922, Vaughn enlisted in the Marine Corps on Sept. 1, 1943, in

Corpus Christi, said R.V. Aquilina, Headquarters Marine Corps History

and Museums Division, who located some of Vaughn's information in

Marine files.

"It's been a long time, but

I remember Warren told me he was going back home to get married and

teach. He had graduated from Southwest Texas Teachers College (now

Southwest Texas University) and was looking forward to getting home,"

Iwatake said. "I can still see his face when I close my eyes, and it

seems like yesterday. I'll never forget Warren for as long as I live."

Another article:

http://www.perkins-smart.com/burmacampaignsociety/archive/news_pdf/Newsletter%2014%20a.pdf

The Burma Campaign Society NEWSLETTER

September 2009

WARREN IWATAKE’S WAR.

George Bush Sr. who later became

US President made his first parachute jump on Chichi Jima during the

Pacific

War when his plane was shot down. I saw his rescue and was happy to

learn that he was picked up by the submarine

Finback. I am also grateful to the captain of the US submarine that

sank our troopship, because if we had not lost

our artillery and ammunition, we would have gone on from Chichi Jima to

Iwo Jima. Our anti-tank platoon, with

which we had trained in Hiroshima, was one convoy ahead of us and

reached Chichi Jima safely, where we met

them. But it was not so lucky. A week later, they were sent on to Iwo

Jima, only a hundred and fifty miles away,

and were all killed. Such is fate.

I had had dual American and Japanese citizenship and had been told by

my high school teacher never to join the

Japanese Army or I would not be able to return to Hawaii. However, I

was attending university in Tokyo in 1943

when the military government ordered all university students to be

drafted into the army. Although they were

exempt from military service, the war was being lost and a hundred

thousand students were drafted, and many

never returned.

I myself did three months basic training in Hiroshima, and life in the

Japanese Imperial Army was a nightmare.

We recruits were constantly reminded that we were fighting for the

Emperor, who was at that time considered to

be a God, and the army tried to pound it into our heads that we should

be willing to sacrifice our lives for him and

for the country. Life was really tough, as we were beaten by our

superiors, and when we were liined up at night

for roll call and our kit was inspected, our faces would be violently

slapped if there was one speck of dust on our

boots.. The beatings were routine and since, in my case, my English was

better than my Japanese, I was singled

out several times because of my enemy background. Since we were in the

artillery, we trained with cannons which

were hauled by manpower. However, things improved after basic training,

as attention was then focused on the

next batch of recruits and we were no longer beaten. After the war some

soldiers called their basic training hell.

I took the name of Pilot Warren Vaughn to honour his memory, as I

became friends with him until he was executed.

Despite being a POW, he managed to smile and tell us jokes. I had been

ordered to join a naval radio facility to

monitor enemy communications and Warren Vaughn was forced to work with

us for a while, and it was he who

caught a message from US Army Headquarters announcing that “all

organized resistance on Iwo Jima has ended.”

One day, a member of our army unit passed by and asked me how the war

was going, and when I told him that

I knew, because of the monitoring, that Japan was losing, he called me

a traitor. The Japanese soldiers did not

know that it was being lost, because the High Command in Tokyo kept

announcing victory after victory for the

Japanese Imperial Army, and during the Battle of Midway, which turned

the tide of the war, and in which Japan

lost three of its top aircraft carriers, Japan announced that it had

won a major victory, sinking several US carriers.

After the war, when the President learned that I had taken Warren

Vaughn’s first name, he called me “a true friend

of America”, and when, in 2004, I was able to visit Childress. Vaughn’s

home town in Texas, with a population

of ten thousand, I received a warm welcome and was made an Honorary

Citizen.

As to the war, my opinion is that wars may be necessary to protect the

democratic way of life and get rid of

dictators, but we must remember that war is a matter of kill or be

killed. I lost my brother, who was only thirteen

when he was killed in his classroom in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima,

and as a result of my experience, I am

opposed to war.

Warren Iwatake

Editor’s note

The above Article is drawn from two Emails which were sent to Akiko

Macdonald.

And another one:

1 family's tradition: Tree that

saw war, survived A-bomb goes up for 70th Christmas

The

Associated Press

Friday,

December 21, 2007

TOKYO: Warren

Nobuaki Iwatake's family has seen more than its share of calamity.

When he was still a child his

father was lost at sea off Hawaii. With no breadwinner, his family was

forced to move to Japan, where Iwatake was drafted during the war. He

lost a brother when the bomb fell on Hiroshima.

But through it all one thing has

remained constant.

The tree.

His parents bought it in 1937, and

his family has brought it out every Christmas since, without fail, even

when that meant risking arrest.

"This tree was a shining light,

because it was a symbol of unity in my family," Iwatake said as he and

his wife put the final touches on the frail, 1-meter-tall (3-foot-tall)

heirloom that is, once again this year, the centerpiece of their small,

neatly kept apartment in Tokyo.

"We have put this tree up every

year for 70 years."

___

Though he considers himself

Buddhist, Iwatake was raised in a Christian tradition. He still keeps a

photo of the tiny wooden church on Maui where he and his five brothers

went to services and Sunday school.

Christmas was always a special time.

His father worked at a merchandise

store, and Iwatake remembers the day he came home with a tree. It was

nothing all that special, just metal-and-plastic, the kind of

decoration that can easily be placed on a table, or in a corner

somewhere. He got a string of lights, too, the kind with the big bulbs.

Soon after, his father died in a

fishing accident. His body was never found.

Iwatake's mother had relatives in

Japan, and took Iwatake's younger brothers there. Iwatake stayed behind

to graduate from high school, then, in 1941, six months before Pearl

Harbor, he moved to Japan as well.

"Things were pretty bad," he said.

"There were war clouds hanging everywhere."

The United States and Britain were

the enemy, and Japan clamped down on overt displays of anything

Western, including Christianity. Though they had grown up speaking

English, Iwatake and his brothers communicated solely in Japanese, and

did their best to hide their past.

But their mother refused to give up

on the tree.

"She was in charge and she wanted

to put it up," Iwatake said. "During the war years, we had to do that

in secret because in wartime Japan it was not welcome. We could have

been arrested."

To keep the neighbors from asking

questions, his mother found a place for it in the back of their house,

on the second floor, away from the windows.

"We were afraid they would report

it to the police, or become suspicious about why we were harboring

Western things," he said. "But we were brought up in the American way

of life. It is something that you cannot forget. It really is something

from the heart."

The year after that first Christmas

in Hiroshima, Iwatake went to Tokyo to study economics at university.

At Christmas, he directed a school play, a nativity story, again

keeping it secret so that the authorities wouldn't get involved.

Then, in 1943, he was drafted and

sent to Chichijima.

___

Chichijima is a tiny island that

virtually no one has heard of. To get there, you go out to the middle

of nowhere, and turn south.

In 1944, Iwatake boarded a

transport ship from Yokohama to assume his duties at a radio monitoring

post on the remote crag. The ship was torpedoed and sunk by an American

submarine, but he survived and was put on an oil tanker.

On the island, Iwatake's English

skills were put to use listening in on U.S. military communications,

and keeping watch over a handful of captured American pilots whose

planes had been shot down on their way to and from bombing raids on

Tokyo.

One day, he was in the hills

digging bunkers when he heard that a plane had just been shot down. He

saw a lone pilot on a bright yellow life raft paddling furiously away

from the island. American planes provided cover, and the submarine USS

Finback surfaced and collected him.

The aviator was 20-year-old George

H. W. Bush, who would later become the American president. Iwatake met

him years later and went back with him to the island. Signed photos of

the two, smiling, are placed prominently about Iwatake's apartment.

But another American left a deeper

impression on Iwatake's life.

Captured POWs were forced to

monitor U.S. radio traffic. One of them was Warren Vaughn, a Texan.

"One night after a bath we were

walking back and I fell into a bomb pit," Iwatake said. "It was pitch

black and I couldn't get out. He reached to me and said to take his

hand. He pulled me out."

Vaughn was monitoring the day Iwo

Jima fell. Japan's defeat was virtually assured. Soon after, several

naval officers called Vaughn and took him to the beach. "He turned

before he left and gave me a sad look," Iwatake said.

For no apparent reason, Vaughn was

beheaded, and his body dumped into the sea.

The atrocities committed against

the POWs — which included acts of cannibalism — remained largely a

secret for the next 50 years. But Iwatake said he did not want Vaughn's

memory to die.

"I thought the best way of

remembering him was to adopt his first name," Iwatake said.

___

Japan surrendered in August 1945,

and Iwatake returned home in December.

"I used to think of those joyous

days in Hawaii at Christmas, when we had food and treats," he said. "On

Chichijima, we were starving."

But Hiroshima was even worse.

"Everything was bad, nothing was

left," he said. "I couldn't even think of the joys of what I

experienced in Hawaii."

Iwatake's younger brother Takashi

had been in the center of the city attending school. His body, like

their father's, was never found.

The Iwatake home was in the eastern

part of the city, behind a small hill that provided a buffer from the

blast. The front end was crushed and burned, but the back stood largely

intact.

And that was where the tree was.

"Japan had surrendered, there was

no food, nothing to celebrate," he said. "Everybody was in shock and a

sad state, but we put it up. My mother put it up."

After the war, Iwatake became an

interpreter for the U.S. government. He moved to Tokyo, and from 1950

he took responsibility for the family tree.

At first, putting it up was more of

a simple tradition than anything else.

His family was once again spreading

out. At one stage, four brothers worked for the Occupation Forces as

interpreters and translators, including Iwatake. He eventually went

back to Tokyo, while his brothers returned to Hawaii. When the Korean

War broke out in 1950, three brothers volunteered, and one served in

Korea.

The Iwatake family remains

scattered.

One brother lives in Chicago,

another on Maui. Another died of cancer, possibly the result of

radiation from the atomic bomb.

But each year, the tree has gone

up. For those not in Tokyo to see it, including Vaughn's cousins in

Childress, Texas, Iwatake, now 84, sends photos. And each year, it

becomes more poignant.

"Gradually, Christmas has become

more meaningful again," he said. "Peace, good will toward your fellow

man, you know? After the war, there was no such thing."

Fumitane Jibutsu

Mentioned by Patrick Aki (half Nisei, half Chinese-Hawaiian; interview):

https://www.thegardenisland.com/2014/07/04/hawaii-news/love-thy-neighbor/

Aki and his brother befriended a

boy from Japan, named Fumitani Jibutsu, who had just moved into their

Kauai neighborhood, an immigrant child who was shunned by everybody

else, except them. It was a welcoming gesture for Jibutsu, whose

parents were Shinto priests and spoke no English. Jibutsu also

struggled with the language, making finding friends almost impossible.

“No one wanted to be his friend because he could not speak English, so

my brother and I befriended him because we were taught to love thy

neighbor,” Michelle wrote about Aki’s memories. Little did Uncle Pat

know then, but Jibutsu would return to Japan and become a soldier for

her army.

.....

Weeks later, the Japanese overtook Wake Island and Aki became a

prisoner of war. Only 450 of the 550 laborers would be taken to POW

camps in Japan, however. The Japanese soldiers executed the others, and

Aki was singled out to be put to death. “They had us kneeling on the

ground, with our heads hanging, each man would look up into the barrel

of the gun to meet his fate as an officer would stand directly in front

of him to help deliver his destiny,” Michelle wrote about Aki’s fate.

“When it came to my turn, I raised my head so that I could see my

executioner and to my amazement, the man that held the gun was Fumitani

Jibutsu. He lowered the gun and just stared at me and before I knew it,

I was taken to Japan as a prisoner.”

Per John Stephan:

Jibutsu Fumitane was, contrary to

Patrick Aki's testimony, born not in Japan but in Lihue, Island of

Kauai on 15 Jan. 1922, was taken by his mother in 1923 to sojourn with

his maternal grandfather in Kano-mura, Tsuno-gun, Yamaguchi-ken,

returned to Hawaii in 1925, attended the Wailua School, where in 1929

he was elected "junior cop." Upon the death of his father, Ginichi

Jibutsu (both of his parents were Shinto priests, Ginichi doubled as a

Buddhist priest), Fumitane departed with his widowed mother, Atsuko

Miyamoto Jibutsu, for Japan on 24 July 1930 (in April, he and his

mother were living in Wailua according to the 1930 US Census). He would

have likely completed primary school, presumably in Kano-mura,

Yamaguchi-ken, around 1937, possiblly entered Middle School, and was

conscripted or volunteered for the IJA (or IJN) in 1941. I could find

no record of either Atsuko Jibutsu or her son Fumitane returning to

Hawaii after the war.

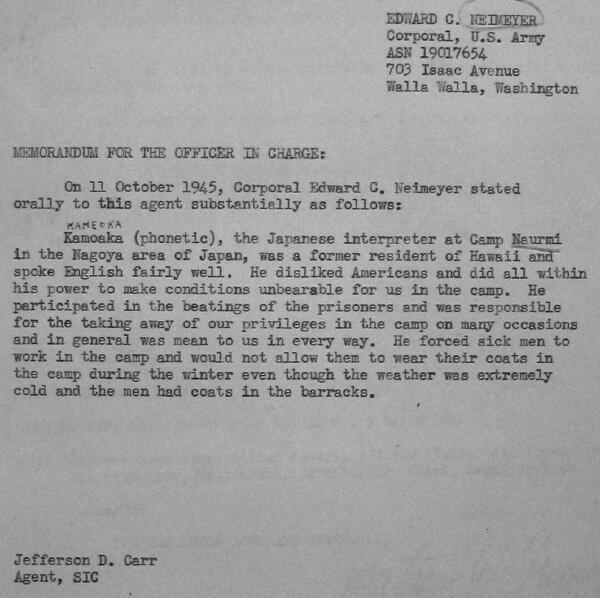

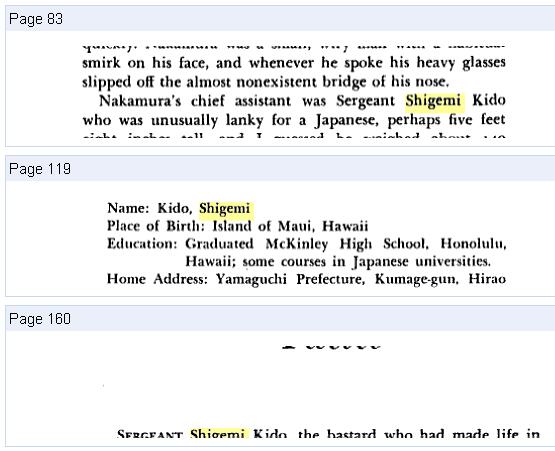

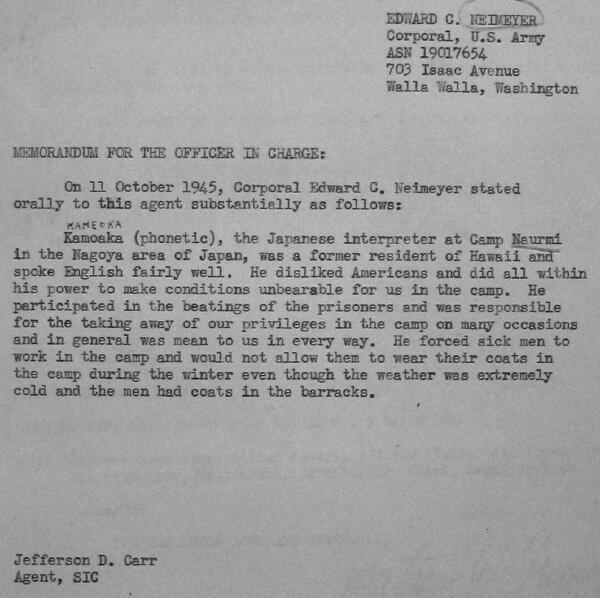

Masaji Kameoka

Nisei? interpreter at POW camp, Nagoya #2 Narumi:

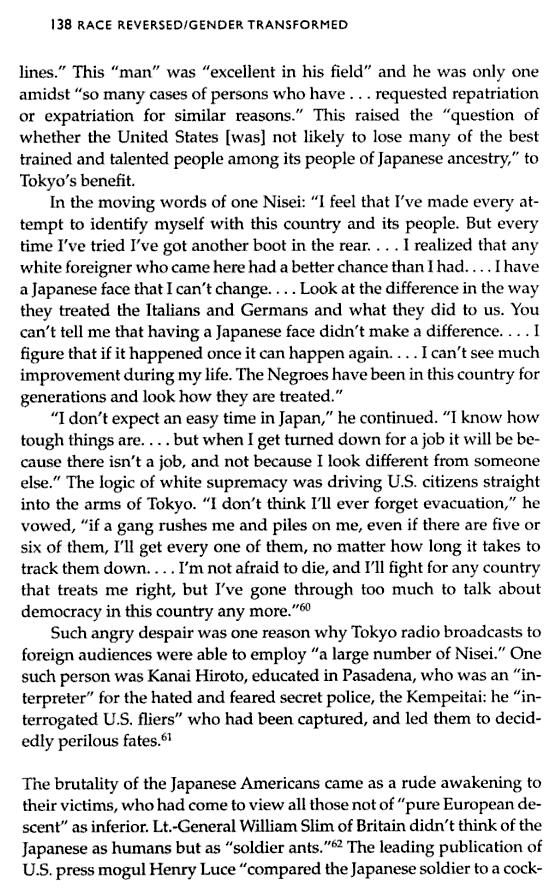

Hiroto Kanai

Interpreter for the Kempeitai in Hiroshima; photo here.

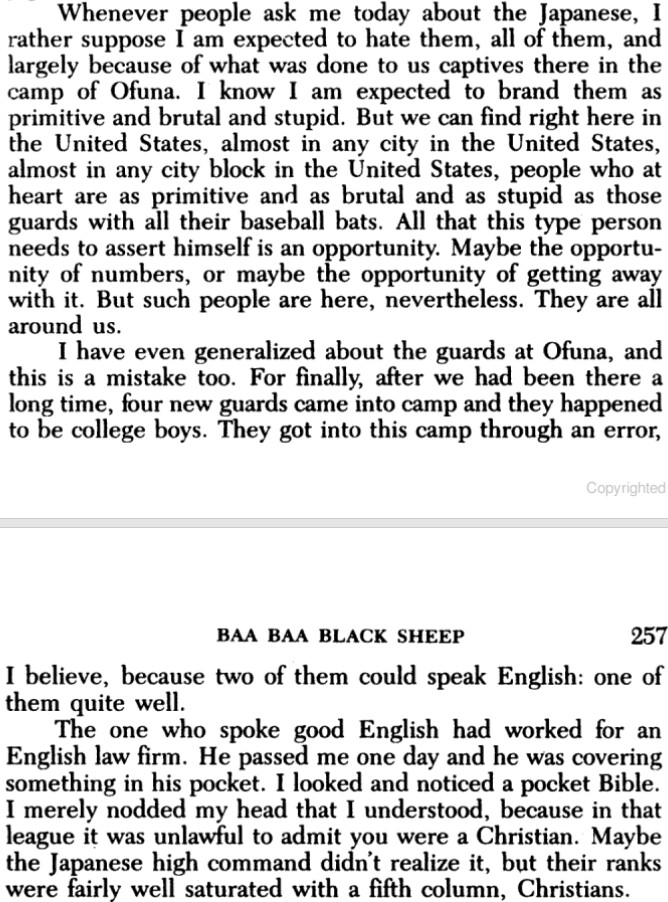

Below page from Race War!: White Supremacy and the

Japanese Attack on the British Empire by Gerald Horne (2005).

Toshiyuki Kano

Toshiyuki

Kano (1914- ). Hawaiian-born Kibei, Salt Lake City. Former military

intelligence officer in the Japanese military.

Tomoya Kawakita

Kawakita was an interpreter at a POW camp in Oeyama, Japan, who was

convicted of war crimes. See here for a Time magazine article: eo9066/Kawakita.html

For basic background info, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kawakita_v._U.S.

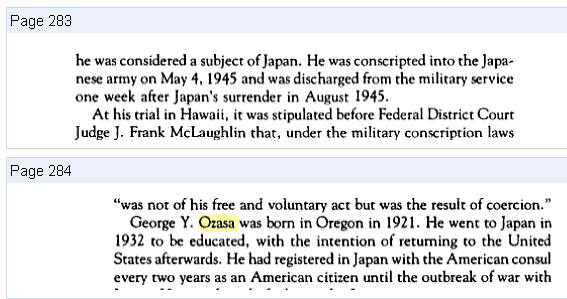

Section in The Bamboo People (PDF) on Kawakita

(p.288~). Note that the judge said that a US citizen owes

allegiance to the United States wherever he may be! So this

should be true for ALL the Nisei who were in Japan during WWII. Yet

this was not brought up in the trials.

He was later "successfully prosecuted for treason" (Kawakita v. United States).

Lengthy chapter on Kawakita (Chapter Four), how he was recognized,

trial, etc.:

America's

Geisha Ally by Naoko Shibusawa, 2006

Mentions other Nisei working at the camp: "Two other Nisei were there

as interpreters: Kawakita’s childhood friend, Meiji Fujizawa, who translated

in the POW camps, and Noboyuki Inoue,

who worked in the company’s administrative office."

Also states that former prime minister of Japan, Takeo Miki, was the

one who helped Kawakita get the job at Oeyama Nickel Industry Company,

and later made appeals to the US Govt. for leniency in dealing with

Kawakita.

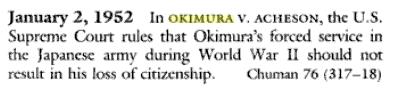

See also this image series re Okimura, Kawakita, Nishikawa (Nisei in

J-military) - Asian Americans and Supreme Court by Kim, in

PDF format.

Los Angeles Times

article:

Los Angeles Times

September 20, 2002

ON THE LAW

POW Camp Atrocities Led to Treason Trial

Tomoya Kawakita claimed dual citizenship, abusing captured GIs in Japan

in World War II, then moving to the U.S.

DAVID ROSENZWEIG, TIMES STAFF WRITER

Army veteran William L. Bruce, a survivor of Corregidor, the Bataan

death march and three years in a Japanese prisoner of war camp,

couldn't believe his eyes as he shopped with his bride one autumn day

in 1946 at the Sears department store in Boyle Heights.

Standing a few aisles away amid the crush of shoppers in that

quintessentially American setting was the man responsible for

brutalizing Bruce and scores of other GIs held captive in Japan's

Oeyama prison camp on Honshu Island.

Tomoya Kawakita, who held dual citizenship in the U.S. and Japan,

served as an interpreter and self-appointed taskmaster at the camp,

earning the nickname "Efficiency Expert" for his methods of inflicting

pain on inmates weakened by malnourishment and forced labor.

"I was so dumbfounded, I just halted in my tracks and stared at him as

he hurried by," Bruce, then 24 and attending college under the GI Bill,

said shortly after the encounter.

"It was a good thing, too," said the former artilleryman. "If I'd

reacted then, I'm not sure but that I might have taken the law into my

own hands--and probably Kawakita's neck."

Instead, Bruce followed him outside the store, jotted down the license

plate number of his car and notified the FBI.

Kawakita, who had returned to the United States after the war and

enrolled at USC, was tried and convicted of treason in U.S. District

Court in Los Angeles and sentenced to death.

The sentence was never carried out. In 1953, President Dwight D.

Eisenhower, responding to appeals from the Japanese government,

commuted Kawakita's death sentence to life in prison. In 1963,

President John F. Kennedy ordered him freed after 16 years behind bars

on the condition that he be deported to Japan and never return.

Now more than half a century since his trial, Kawakita holds the

distinction of being the last person prosecuted for treason against the

United States.

He was represented at his federal court trial by Morris Lavine, a

colorful Los Angeles criminal defense lawyer, who was fond of

describing himself as "attorney for the damned." Lavine's clients

ranged from the indigent, whom he represented at no charge, to the

likes of mobsters Mickey Cohen and Johnny Roselli, and Teamsters boss

James Hoffa.

Heading the prosecution team was U.S. Atty. James M. Carter, who went

on to become a federal appeals court judge.

More than a dozen former POWs testified against Kawakita. They

described how he forced prisoners to beat one another, and then beat

those he thought didn't hit the other prisoners hard enough. They

accused him of forcing prisoners to run laps until they collapsed in

exhaustion simply because they had finished their work assignments

early.

The camp was set up next to a nickel ore mine and processing plant,

where most of about 400 American POWs were forced to work. Kawakita was

employed by the mining company.

Once, he forced a prisoner to carry a heavy log up an icy slope. The

prisoner fell and suffered a serious spinal injury. Fellow POWs

testified that Kawakita waited five hours before summoning help for the

injured American.

They also recalled being taunted by Kawakita with comments such as: "We

will kill all you prisoners right here anyway, whether you win the war

or lose it."

And, "You guys needn't be interested in when the war will be over,

because you won't go back. You will stay here and work. I will go back

to the States because I am an American citizen."

Kawakita's citizenship proved to be a crucial issue during the trial

and subsequent court appeals.

By definition, treason can be committed only by someone owing

allegiance to the United States.

Born in Calexico to Japanese parents, Kawakita held dual citizenship

under U.S. and Japanese laws. In 1939, at the age of 18, he went to

Japan to attend school. He remained there after the outbreak of war,

graduating from Meiji University.

At the trial, Lavine advanced a novel argument. As a dual U.S. and

Japanese citizen, he argued, his client owed exclusive allegiance to

the country in which he resided. In this case, Japan. Lavine also

contended that Kawakita had effectively renounced his U.S. citizenship

by signing a family census register maintained by Japanese authorities.

In his instructions to jurors, U.S. District Judge William C. Mathes

made it clear that if they found that Kawakita genuinely believed he

was no longer an American citizen, then they must acquit him of the

treason charges.

Sequestered during deliberations, the jury struggled mightily to

resolve the question--declaring several times that they were hopelessly

deadlocked. But ultimately they found Kawakita guilty on eight of 13

overt acts of treason charged by the prosecution.

When he appeared for sentencing, Kawakita continued to insist he was

innocent. "As I have been found guilty by the jury, I ask your honor

for mercy," he said.

By law, Mathes had leeway to impose a sentence ranging from a minimum

of five years in prison to a maximum of death at Alcatraz.

He chose the latter, saying: "Reflection leads to the conclusion that

the only worthwhile use for the life of a traitor, such as this

defendant has proved to be, is to serve as an example to those of weak

moral fiber who may hereafter be tempted to commit treason against the

United States."

Today, most of those involved in the case are either dead or, if alive,

could not be located. One exception is William J. Kelleher, then a

federal prosecutor and now a senior U.S. District Court judge in Los

Angeles.

Although he did not take part in the trial, Kelleher was assigned to

draft the government's response to Kawakita's appeal of his conviction.

As a result, he immersed himself in every detail of the case.

In an interview last week , Kelleher recalled being visited at his

office by Bruce and two other former POWs while he was working on his

brief for the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

"Me and the boys had a little meeting last night," he said Bruce told

him. "And we want you to know that if he ever gets out, we'll be

waiting for him."

Fortunately, Kelleher said, the appeals court upheld Kawakita's

conviction by a 3-0 vote.

It was a much closer call when the appeal went before the U.S. Supreme

Court in 1952. The vote was 4 to 3 to uphold the conviction. Two of the

court's nine justices disqualified themselves.

At the crux of the case was this question: Where does the allegiance of

a dual citizen lie when two nations, each claiming his loyalty, go to

war?

"Of course, a person caught in that predicament can resolve the

conflict of duty by openly electing one nationality or the other," said

Justice William O. Douglas, writing for the majority.

Kawakita, the court said, chose neither option, trying instead to hedge

his bets on the war's outcome while freely performing acts of hostility

against the U.S.

"One who wants that freedom can get it by renouncing his American

citizenship," Douglas wrote. "He can not turn it to a fair-weather

citizenship, retaining it for possible contingent benefits but

meanwhile playing the role of the traitor. An American citizen owes

allegiance to the United States wherever he may reside."

Related treason case in the US regarding the three Shitara sisters can be found

at: Prosecution of the Shitara Sisters.

Another article here, in four parts: Betrayal on Trial: Japanese American

"Treason" in World War II.

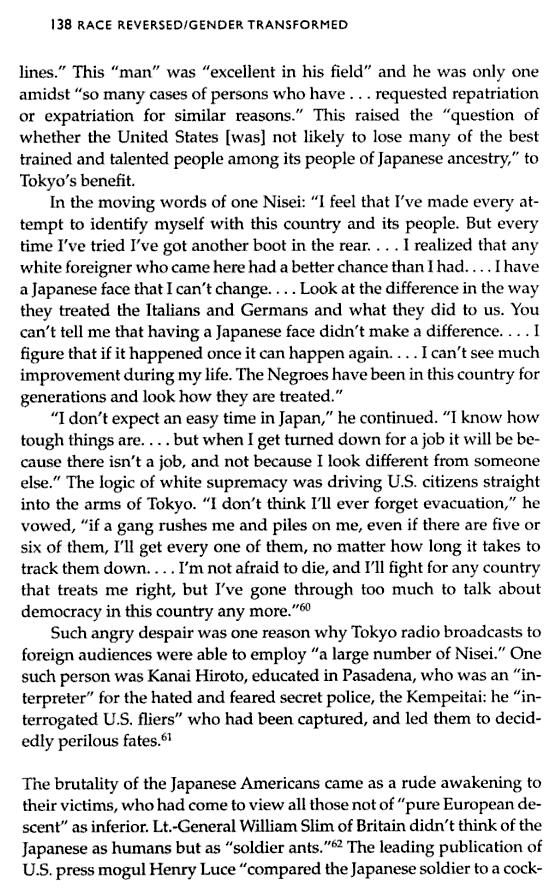

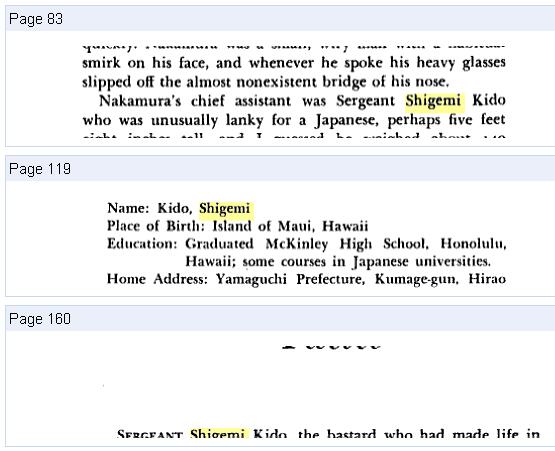

Shigemi Kido

From The Two Worlds of Jim Yoshida

by Yoshida and Hosokawa:

Then I found Sergeant Kido's file. Apparently it hadn't been

transferred back to Japan yet. My eyes widened and I broke out in a

cold sweat at what I read.

Name: Kido, Shigemi

Place of Birth: Island of Maui, Hawaii

Education: Graduated McKinley High School, Honolulu,

Hawaii; some courses in Japanese universities.

Home Address: Yamaguchi Prefecture, Kumage-gun, Hirao

Village.

Kido was born in Hawaii! Educated in Hawaii! That made him a Nisei,

just like mel And he lived in Japan in the same village where my father

was born, the village where I had lived before being conscripted! (p.

119)

Richard Kotoshirodo

http://michellemalkin.com/2004/08/06/book-notes-4/

Finally, in knocking down my

argument for the Roosevelt administration’s military rationale, Greg

focuses on a few of my points and ignores the rest of the evidence of

bona fide security threats that I present to readers, including:

- the Niihau incident, in which a Japanese-American couple and a

Japanese permanent resident alien sided with a downed Japanese pilot in

a violent effort to take over a tiny Hawaiian island;

- Japan’s ascendance throughout the Southeast Asia, and the efforts of

ethnic Japanese residents throughout southeast Asia to assist Japan’s

conquering troops;

- the numerous attacks on U.S. ships by Japanese submarines just off

the West Coast;

- the thousands of ethnic Japanese in Hawaii and the West Coast who

were members of pro-Japan groups considered subversive;

- the Honolulu spy ring that Richard Kotoshirodo assisted, which

provided critical information to Japan that was used to design the

Pearl Harbor attack;

- the Los Angeles-based spy ring led by Itaru Tachibana, which included

numerous ethnic Japanese residents; and

- the thousands of U.S.-born Japanese-Americans who served in the

Japanese military.

See The Broken Seal: The Story of 'Operation

Magic' and the Pearl Harbor Disaster by Farago for quite a

lot of info, p. 145~.

Jimmy Matsuda

Nisei Kamikaze: Sunnyvale Gardener

Recalls Life on the Edge of Extinction

By editor. Posted on Friday, September 11,

2009.

Published in the Nichi Bei Times

Weekly Sept. 3-9, 2009.

By KOTA MORIKAWA

Nichi Bei Times

Jimmy Matsuda, an 82-year-old

Japanese American gardener in Sunnyvale, Calif., had never talked about

the experience he had as a kamikaze pilot during World War II, until a

small plastic figure of a Japanese Zero plane caught his grandson

Jonathan’s attention two years ago.

The then-11-year-old wondered what

the item on his grandfather’s desk was. After Jonathan asked his father

about the airplane, the elder Matsuda decided to talk about his wartime

experience.

“I believed I should talk about my

life story,” he said. “Otherwise, our grandchildren will never know

what happened.”

Born in Hood River, Ore., the Nisei

(second-generation Japanese American) visited Japan for Christmas

vacation in 1938 at the age of 11. While there, he got sick and missed

the ship returning to the United States. His whole family decided to

stay in Japan for good.

In April of 1943, after graduating

from high school, Matsuda volunteered to enlist in the Imperial

Japanese Navy. Back then, Navy pilots were already known to eventually

become kamikaze pilots. Yet he had no fear of certain death.

“The war atmosphere seemed

overwhelming,” Matsuda said. “Everybody was chanting for the war.”