Washington, D. C.

[March 1943]

[March 1943]

WORK OF THE WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

An Anniversary Statement by Dillon S. Myer

Director of the War Relocation Authority

An Anniversary Statement by Dillon S. Myer

Director of the War Relocation Authority

One year ago on March 18, 1942, the President signed Executive Order 9102, creating the War Relocation Authority. The primary function of the new agency was to aid the Western Defense Command of the Army in the relocation of 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry which the Commanding General had determined should be excluded from the strategic coastal area. The exclusion already had been ordered, on March 2, and voluntary evacuation was taking place. From areas scattered throughout the West came disquieting reports of difficulties which the voluntary evacuees were encountering in settling or along the way to new homes. It became apparent that voluntary relocation was not going to be successful. In collaboration with the officials of the new relocation agency, the Army worked out plans for an orderly evacuation of the coastal areas, which included at first the western third of Washington, Oregon, and California, and also the southern portion of Arizona. Later, the entire state of California was included in the evacuated areas.

Objective, Quick Resettlement

From the beginning, the objective was to relocate the evacuated people as quickly as possible, in order that their removal from private life and productive work would be brief. The War Relocation Authority began a search for locations where wartime communities might be established in the interior of the country. Land that could be developed for agricultural purposes, water supply, access to transportation, and electric power were among the requirements. An effort was made to find land that could be obtained without displacing large numbers of people and removing them from agricultural production. Ten sites were found, and Army engineers supervised the construction of ten new communities, two each in California, Arizona, and Arkansas, and one each in Utah, Idaho, Wyoming and Colorado.

Guards Demanded

Early consultations with state officials indicated that they would not be responsible for law and order in the vicinity of the relocation centers. Accordingly, it was deemed necessary to have the relocation centers guarded by military police for the protection of the evacuees as well as the public outside.

The actual evacuation was carried out in an orderly manner by the military and evacuees at first were quartered temporarily under military supervision in cantonments hastily constructed within the evacuated area. Later, as construction of the relocation centers was completed, the people were moved by the military authorities to the relocation centers, where they came for the first time under jurisdiction of the War Relocation Authority. The movement to the relocation centers took place over a period of several months, from late May to early November 1942.

Way Stations

For most of the evacuated people, the relocation centers are way stations; places where they can live until they can be reabsorbed into the normal life of the nation. While they are in relocation centers, the War Relocation Authority provides them with food, lodging, medical care, and education for the children at public expense. Everyone is encouraged to work, and about 40 percent of the population is actually employed in the relocation centers, about the same proportion as before evacuation. Those who work are paid nominal wages, of $12, $16 or $19 a month, depending on the kind of work and the amount of training and skill required to perform it.

While an effort is made to have life in a relocation center approach life in a normal community, no more than a remote approach is possible. The residents of a relocation center do not leave the relocation area without special permission. During the daylight hours they may move within the relocation center, which in each instance includes several thousand acres, but after dark they are confined to the residence area, usually about a mile square. This area is usually fenced with barbed wire.

Living quarters are barrack-type structures, one story high, divided into compartments about 20 by 25 feet for a family of 5 or 6 people. In some instances the limitations of space require that two or more families share a compartment. There is no family type cooking, and everyone eats in dining halls, about 275 to a dining hall. The food is sufficient, but not elaborate. All rationing restrictions are followed and meat allowances were established several weeks ago. The War Relocation Authority established a maximum allowance of 45 cents per person per day in estimating food costs, and at the present time food costs are actually about 40 cents a day for each person, this

in the

face of rising food prices. Menus include both American and Oriental

type dishes because the older people, aliens, favor the foods with

which they were familiar in Japan, rice, fish, tea, leafy greens and

pickles of various types; their children, born in the United States

prefer meat and potatoes and other typically American foods. [PHOTO:

"Takeshi Shindo, Manzanar Free Press Reporter, tastes some home cooked

soup, prepared on the electric plate in his barracks home." (Manzanar,

02/12/1943)

in the

face of rising food prices. Menus include both American and Oriental

type dishes because the older people, aliens, favor the foods with

which they were familiar in Japan, rice, fish, tea, leafy greens and

pickles of various types; their children, born in the United States

prefer meat and potatoes and other typically American foods. [PHOTO:

"Takeshi Shindo, Manzanar Free Press Reporter, tastes some home cooked

soup, prepared on the electric plate in his barracks home." (Manzanar,

02/12/1943)Evacuees Do The Work

The War Relocation Authority has a relatively small administrative staff at each relocation center, but most of the work, administrative and otherwise, is done by the evacuees. In any community, a fair proportion of the population is concerned with procuring, distributing, preparing and serving food, and so the largest group of employees in any relocation center is attached to the dining halls and the food warehouses. Others work on the farm, in the administrative offices, on the newspaper staff, in the co-operative stores, with the construction and maintenance crews, or in the hundreds of varying types of work which are necessary for the operation of any city.

Army Production

Several hundred of the American citizens in two relocation centers are engaged in making camouflage nets for the Army. At two of the relocation centers last summer and fall the evacuees produced several hundred truck loads of vegetables, enough to meet the immediate needs of the residents where they were produced, make shipments of fresh produce to other relocation centers, and leave thousands of bushels to be stored for later use. One of the centers in Arizona has had about 500 acres in vegetables this winter. Poultry and hog production is well under way at several of the centers; a beef herd is being established in one and a dairy herd at another. Almost all the centers will have vegetable production during 1943 sufficient to meet their year-round needs, and a major share of their requirements for pork and poultry products.

Each relocation center has a hospital, and a staff composed largely of evacuee physicians, nurses, pharmacists and aides, with non-Japanese in only the supervisory positions. Since living conditions do not permit home care of the sick, almost every illness is a hospital case. The rate of illness has been low and no contagious disease has reached serious proportions.

The school system, supervised by non-Japanese, is planned to meet the standards of the state in which the center is located. Because of the shortage of materials, no regular school buildings have been constructed as yet, and classes have been held in buildings originally intended for living quarters or for recreation halls. Some of the shop work necessary to the operation of the center is utilized in vocational training. The regular school course covers the elementary and high school grades, and in addition extensive programs of adult education are carried on, sometimes with members of the regular school

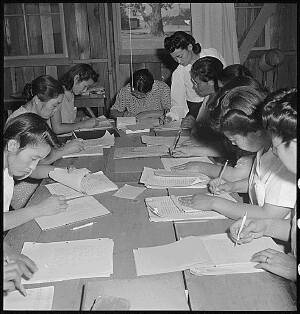

staff and

sometimes with evacuees as teachers. One of the most popular

courses for foreign-born adults is English. Courses in American history

and American geography also are much in demand. [PHOTO: "Part of a

class under the Adult Education Program at this War Relocation

Authority center. It is composed of Issei and Kibei evacuees who are

studying the Ideals of American Citizenship and the English language

with which they are unfamiliar. There are 18 such classes, each

averaging 20 volunteer members and conducted by a volunteer instructor.

This is a class in penmanship with Miss Doris Nakagawa, 25, as

instructor. She is an American citizen who finished High School in this

country and attended Glendale Junior College upon her return from two

years in the Woman's College in Japan." (Manzanar, 07/09/1942)]

staff and

sometimes with evacuees as teachers. One of the most popular

courses for foreign-born adults is English. Courses in American history

and American geography also are much in demand. [PHOTO: "Part of a

class under the Adult Education Program at this War Relocation

Authority center. It is composed of Issei and Kibei evacuees who are

studying the Ideals of American Citizenship and the English language

with which they are unfamiliar. There are 18 such classes, each

averaging 20 volunteer members and conducted by a volunteer instructor.

This is a class in penmanship with Miss Doris Nakagawa, 25, as

instructor. She is an American citizen who finished High School in this

country and attended Glendale Junior College upon her return from two

years in the Woman's College in Japan." (Manzanar, 07/09/1942)]Leisure time activity has been developed almost entirely as a result of the evacuees' own initiative. Arts and crafts are popular with evacuees of all ages; the younger people, almost all of them American citizens, enjoy about the same kinds of recreation that any other group of young Americans do. There are softball teams by the hundreds; during the past winter, the boys and girls have been playing basketball, usually out-of-doors, and they have provided competition for nearby high school teams. The young people have brought to the relocation centers the same tastes in activity that they learned in American schools and universities; so they have glee clubs and choirs, they jitterbug to the latest dance tunes, they have their own orchestras; the Hawaiian influence is rather common, for many of the people came to the mainland of the United States by way of Hawaii, and so Hawaiian string orchestras are fairly common.

Woodie Ichihashi band. (Tule Lake, 11/01/1942)

Freedom of Speech and Religion

Evacuees have complete freedom of speech in the language of their choosing. They have freedom of religion, and Buddhist, Catholic, and Protestant services are held every Sunday, in recreation halls or dining halls, for no church buildings have been erected. A little more than half of the people are Buddhists, and the Christian church membership covers a wide range of denominations. A higher percentage of the American-born are Christians than is the case with aliens.

Anyone visiting a few of the ten relocation centers would be impressed by the U.S.O. Clubs in operation at several of the centers for soldiers of Japanese ancestry who return from the Army on furlough to visit relatives and friends; they would hear at one relocation center about three brothers who volunteered for the Army together, only to be followed a few days later by four brothers of another family. The post office at each relocation center sells war bonds and stamps, but the postmaster at one center was caught inadequately supplied the other day when an evacuee walked in and asked for $3,000 worth of war bonds. A visitor to a school room where sixth graders were making drawings was impressed by the airplanes produced by one young artist. His pictures showed American fliers shooting Japanese planes out of the sky. A typical community sing of the younger people is almost sure to include such songs as "Let Me Call You Sweetheart" and "Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition."

Complex Problem

The foregoing statement summarizes some of the general aspects of the relocation center life, but it is an over-simplification. The situation is very complex. The uninitiated person is apt to regard the evacuees as a homogeneous group, when nothing could be further from the truth. They include the old and the young, alien- and native-born, Japanese and American backgrounds, some strongly American in their sympathies, other actively pro-Japanese, and still others in a middle ground; some have determined to make the best of a bad situation and to do whatever is necessary to keep the community in operation; others are embittered and express their bitterness in a generally defiant attitude; there are

roughneck elements in some of the

centers as in any city in striking contrast to the gentility of the

majority; there are well-to-do families, and others who are living

better in a relocation center than they were able to live outside.

A great many are university graduates and others are virtually

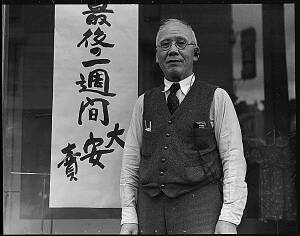

illiterate. [PHOTO: "Father of Dave Tatsuno who has been a merchant in

San Fransisco for forty years. He is now preparing for evacuation to an

Assembly center." Sign: "Last week -- Big Bargain Sale" (04/04/1942)]

roughneck elements in some of the

centers as in any city in striking contrast to the gentility of the

majority; there are well-to-do families, and others who are living

better in a relocation center than they were able to live outside.

A great many are university graduates and others are virtually

illiterate. [PHOTO: "Father of Dave Tatsuno who has been a merchant in

San Fransisco for forty years. He is now preparing for evacuation to an

Assembly center." Sign: "Last week -- Big Bargain Sale" (04/04/1942)]The difference in culture brought about some significant rifts in sentiment between the aliens and their American-born children. In many instances, there are schisms among the aliens and among the American citizens, some of them dating back to pre-war days, some of them developed in the relocation centers. Out of these factional disputes have grown certain administrative problems, some of which have had public attention. As a rule, the more serious difficulties have been over-simplified to the general public and have been labeled "pro-Axis," when as a matter of fact most of the differences of opinion have found staunchly pro-American evacuees on both sides of the question. Many loyal Americans have chosen various means of expressing their protests over un-American treatment which they have received, and such protests are easily misinterpreted.

Relocation Centers Undesirable

After many months of operating relocation centers, the War Relocation Authority is convinced that they are undesirable institutions and should be removed from the American scene as soon as possible. Life in a relocation center is an unnatural and un-American sort of life. Keep in mind that the evacuees were charged with nothing except having Japanese ancestors; yet the very fact of their confinement in relocation centers fosters suspicion of their loyalties and adds to their discouragement. It has added weight to the contentions of the enemy that we are fighting a race war; that this nation preaches democracy and practices racial discrimination. Many of the evacuees are now living in Japanese communities for the first time, and the small group of pro-Japanese which entered the relocation centers has gained converts.

As an example of what has happened to many of the evacuated people, take the case of one man who was born in Hawaii and served in the American Army in France during 1917 and '18. He was a leader among the Japanese Americans of his community and was a positive force for Americanization. I can only surmise as to what went on in his mind during the evacuation period and afterward, but I do know that soon after he came to the relocation center he turned from strongly pro-American to strongly anti-American, and became an agitator for resistance to the WRA administration. He turned his back on America because he felt America had turned its back on him. Continued segregation in the relocation centers has resulted in making many individuals bitter and disillusioned; only the hope of being able to resume a normal life can keep them from being social and political misfits for the rest of their lives.

There are approximately 40,000 young people below the age of 20 in the relocation centers. It is not the American way to have children growing up behind barbed wire and under the scrutiny of armed guards. Living conditions in the centers almost preclude privacy for individuals, and family life is disrupted. Family meals are almost impossible in the dining halls, and children lack the normal

routine home duties which help to build good discipline. One of the

major worries of parents in the relocation centers is the way the

children are "getting out of hand" as a result of the decrease in

parental influence and the absence of the normal regimen of family

economy and family life. [PHOTO: "Mealtime during early days after

evacuation at Manzanar. In housing, as well as at mealtime, family life

is preserved." (04/01/1942)]

routine home duties which help to build good discipline. One of the

major worries of parents in the relocation centers is the way the

children are "getting out of hand" as a result of the decrease in

parental influence and the absence of the normal regimen of family

economy and family life. [PHOTO: "Mealtime during early days after

evacuation at Manzanar. In housing, as well as at mealtime, family life

is preserved." (04/01/1942)]Leave Program

Last July the War Relocation Authority announced a policy of permitting American citizens whose loyalty was beyond question to leave relocation centers to live outside. On the first of October this policy was broadened to include aliens as well as citizens. Only a few evacuees took advantage of this opportunity at first, because most of them had few contacts in the interior of the country which would result in jobs or other means of support.

In recent months, however, the War Relocation Authority has placed staff members at strategic points over the country to contact employment agencies and to make known to them the fact that loyal Japanese Americans with training and experience would be available to help meet the manpower shortage. We have worked closely with the War Manpower Commission, and with the U. S. Department of Agriculture. Private groups, especially the churches, have been exceedingly helpful in establishing local contacts and in developing understanding of the situation. To date approximately 3000 evacuees have left the relocation centers under our indefinite leave procedure.

Farm workers, farm operators, domestic servants, hotel and restaurant workers, and wives and sweethearts of Japanese Americana soldiers leaving to join their husbands or fiances are most numerous among the evacuees who have left the relocation centers to date. The range of employment, however, is quite extensive, and it includes a great deal of war work.

War Work

One of the evacuees who has been successfully relocated is a draftsman with a firm which makes machines for marking bombs. This young draftsman helped to design the machines which marked the bombs that General Doolittle's men dropped on Tokyo. In another factory, two young engineers who left relocation centers not so long ago, are working on parts for bomb sights. A few days ago an evacuee reported for work as a welder in a midwestern plant working on war contracts. At present only those evacuees whose records have been carefully studied including the records of the WRA and the FBI, and found satisfactory, and who have jobs or other means of support, are permitted to leave the relocation centers.

Army Accepts Evacuees

On January 28, the War Department announced that a combat team of Japanese Americans would be formed, to be recruited on a volunteer basis from American citizens of Japanese ancestry in the relocation centers, in Hawaii, and on the mainland outside the relocation centers. More than a thousand Americans in relocation centers volunteered. This was a much smaller number than volunteered in Hawaii, which in my opinion is a commentary on the effect of discrimination and relocation on the mainland, as opposed to the almost complete assimilation of the Japanese which has taken place in Hawaii.

As part of the process of recruiting Army volunteers, all adults in relocation centers were required to fill out questionnaires which would give much information regarding their attitudes and loyalties. The questionnaires filled out by citizen males were to be used in selecting candidates for the Army, or candidates for work in defense plants; while those filled out by the aliens, and women and citizen males over military age were to be used in determining which of the evacuees would be granted permits of indefinite leave from the relocation centers, and their qualifications for war work. One of the questions dealt with loyalty to the United States. It sharpened the issue of loyalty as it had not been done before. The preliminary results of the registration indicate that there are many thousands who manifestly want to be Americans, while others want to be Japanese.

Removal of Restrictions Advocated

For those who will be classed as unquestionably loyal, we advocate lifting of restrictions of all types, except those which apply to all residents of the nation under wartime conditions; we feel they should be permitted to leave the relocation centers as they wish to and work wherever they may be able to establish themselves. There will be others of mixed sympathies but not dangerous to this nation, who could serve the country and themselves better outside of relocation centers. They should be granted the opportunity of leaving the relocation centers and living in the interior of the country, although they would be restricted in some respects. Then, there are others who have indicated that they prefer to be regarded as Japanese, regardless of their place of birth or their years of residence in this country. They should be required to remain in detention for the duration.

We are convinced that segregation of loyal Americans from the disloyal element is essential. The objective of such segregation should be to move the loyal citizens and law abiding aliens as rapidly as possible into the mainstream of the social and economic life of the nation. Any other approach would lead to further frustration and embitterment and waste of manpower.

-- Table of Contents --