ANNUAL REPORT

of the DIRECTOR

WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

TO THE

SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR

Reprinted from the

Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior

for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1945

of the DIRECTOR

WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

TO THE

SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR

Reprinted from the

Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior

for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1945

War Relocation Authority

DILLON S. MYER, Director

->->-> <-<-<-

DILLON S. MYER, Director

->->-> <-<-<-

The most important turning point in the comparatively short history of the War Relocation Authority program came toward the end of 1944. On December 17 the War Department announced the revocation of the mass exclusion orders under which it had evacuated all persons of Japanese descent from the West coast area in 1942 and through which it had prohibited their return to that area (except under special military permit) for almost 3 years. Basing its action primarily on the satisfactory progress of the war in the Pacific, the War Department immediately replaced the wholesale exclusion with a greatly modified system of control under which it continued to exclude only those individuals of Japanese descent whose personal records appeared to warrant such restriction. The revocation, designated to take effect on January 2, ended the wartime ejection of the great majority of West coast Japanese from their former homes and marked the beginning of the end of the War Relocation Authority program.

The War Relocation Authority which had been maintaining relocation centers as temporary shelters for the evacuated people and meanwhile helping as many as possible to become reestablished in normal communities outside the western exclusion zone, immediately took steps to realign its basic operations. First, it broadened the scope of its resettlement activities to take in the former evacuated area and thus cover the entire United States. Second, it made plans to speed relocation movement from the centers in order to close all centers except Tule Lake within 6 to 12 months. Third, it abandoned its leave regulations, with the result that all center residents, except those specifically designated for detention by the War Department or the Department of Justice, were free to leave the centers at any time.

With these changes, the Authority was ready for the first time to move indefinitely toward the ultimate liquidation of all its operations. When the revocation order took effect on January 2, there were slightly over 80,000 persons of Japanese descent still residing in the 9 War Relocation Authority centers, including the Tule Lake Segregation Center of northern California. Over 35,000 -- or nearly one-third of the total group that had come under War Relocation Authority's custodianship -- had left the centers over a period of more than 2 years to take up residence in cities and towns all the way from Spokane, Wash. to Boston, Mass. Of the 80,000 who still remained, the War Relocation Authority calculated that approximately 20,000, consisting mainly of Tule Lake residents, would be either personally designated for detention by the War and Justice Departments or members of the detainees' immediate families. This left a total of 60,000 who had to be assisted in making the transition back to private life before the end of December 1945. Thus the War Relocation Authority was faced on January 2 with the task of completing in 1 year almost twice the volume of relocation which it had managed over the preceding 2-year period.

Several factors, however, tended to reduce the magnitude and complexity of the job. Aside from the skill which War Relocation Authority personnel had gradually gained in relocation after 2 years of intensive experience, there was the overwhelming fact of the Army's revocation order. No longer was it necessary for the average center resident to choose between remaining in the restrictive environment of a center and striking out into unfamiliar section of the country; the great majority were now free, if they wished, to return to their former homes. Moreover, public acceptance for people of Japanese descent through the country was probably at an all-time high. The remarkable exploits of Japanese American soldiers in every major theater of war -- and particularly the Italian front -- had effectively exploded the old cliche that no persons of Japanese ancestry can possibly be loyal to the United States. The excellent work record and exemplary civic behavior of nearly all resettlers from the centers had served further to dispel previous fears and antagonisms. With employment opportunities still running high and with citizen groups (as well as previous resettlers) working to help relocation in almost every major city of the Nation, the stage was set for a record movement out of War Relocation Authority centers and completion of the assignment within the scheduled time.

In order to prepare for a greatly enlarged volume of relocation and a rapidly dwindling center population, the War Relocation Authority on the day after the revocation announcement revised somewhat drastically its whole program of center operations. All activities except those which were absolutely essential and those which contributed toward relocation were scheduled for termination at the earliest feasible date. Construction was brought virtually to a standstill and even maintenance work was sharply curtailed. Crop production on the agricultural lands of the centers was eliminated entirely except for completion of the winter vegetable program at the two centers in Arizona. All further purchase of livestock was halted and plans were made for full utilization of

existing

flocks and herds.

Announcement was made that center schools would close

permanently in June at the end of the academic year. Cooperative

business enterprises, operated by the evacuee residents, were

advised to start planning at once for eventual liquidation. By the end

of June practically all of these changes had either been achieved or

were well on the way to realization.

[PHOTO: "Two clerks, Hannah Takeoka (left) and Namie Hamada (right) the

Jerome Cooperative Enterprises Dry Goods Store in Block 35.“ (11/1943)]

existing

flocks and herds.

Announcement was made that center schools would close

permanently in June at the end of the academic year. Cooperative

business enterprises, operated by the evacuee residents, were

advised to start planning at once for eventual liquidation. By the end

of June practically all of these changes had either been achieved or

were well on the way to realization.

[PHOTO: "Two clerks, Hannah Takeoka (left) and Namie Hamada (right) the

Jerome Cooperative Enterprises Dry Goods Store in Block 35.“ (11/1943)]In submitting budget estimates to the Bureau of the Budget and the Congress shortly after announcement of the West coast revocation, the War Relocation Authority forecast that 16,000 of the 60,000 "relocatable" persons who could be relocated and who were residing in centers on January 2 would leave before the end of June. The actual number who relocated during that period was 15,907. Of this number, 4,922 returned to the evacuated zone while the remainder -- many of them dependent family members following their previously relocated breadwinners -- chose to resettle in other parts of the Nation. When the fiscal year ended, the total number of relocations for the preceding 12 months stood at 24,679 and the cumulative total covering the entire period since establishment of the War Relocation Authority program was 51,412. Of the 44,000 "relocatables" still residing in centers, it was anticipated that fully half would ultimately return to their communities of prewar residence in the far Western States.

RESETTLEMENT ACTIVITIES

Field Organization

Field Organization

One of the first steps which the War Relocation Authority took after revocation of the exclusion orders was to set up a field organization in the West Coast States similar to that which had previously been functioning throughout the rest of the country. Dividing the coastal region into three broad areas -- northern California, southern California, and the northwest -- the Authority established its principal field offices at San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle. District offices, to handle relocation problems at the local level, were also created in these three cities as well as in 15 others such as Fresno, Santa Barbara, Sacramento, and Portland. Meanwhile the activities of field offices in several other sections of the country were slightly curtailed and four of these offices were discontinued.

Public Acceptance

Except in some parts of the Pacific coastal area, public acceptance of relocating evacuees was not a major problem of the War Relocation Authority during the fiscal year. Of the nearly 20,000 evacuees who left relocation centers for destinations outside the former exclusion zone, less than a dozen reported any serious difficulties of community adjustment, and all of these cases were eventually worked out satisfactorily.

In many communities of California, Washington, and Oregon, however, hostility toward the evacuated people and opposition to their return assumed serious and rather widespread proportions. This was particularly true in the interior agricultural valleys of all three States and in some rural sections along the California coast; acceptance in the major coastal cities, aside from some attempts at boycott of evacuee crops in the produce markets, was generally good throughout the entire period.

After revocation of the exclusion ban, antievacuee feelings, which had been simmering throughout the fall, suddenly erupted simultaneously at several places in the coastal States. At first they took the comparatively harmless (but nonetheless reprehensible) form of hostile "mass" meetings, resolutions adopted by various organizations opposing return "at least until after the war," discriminatory signs posted in shop windows, formation of new citizens' leagues specifically for the purpose of working against return, and unfriendly editorials or paid advertisements in the local newspapers.

In the Northwestern States resistance to the return of the evacuees was very largely confined throughout the whole period to these and similar "within the law" types of discrimination. But in several of the California localities, as the evacuee continued to come back in increasing numbers despite such menacing gestures, the hoodlum element among the opposition began resorting to attempted violence and open intimidation.

By the end of June 34[30] such incidents -- involving attempted arson or dynamiting, shots fired into the homes of returned Japanese, and threats of bodily harm -- were recorded. The worst spots were Merced and Fresno Counties, with seven shootings each; and Placer County, which had an attempted arson and dynamiting coupled with a shooting. Fortunately, no evacuee was actually injured in these lawless forays. Property damage, however, was considerable, and the terrorism which prevailed over wide areas of California undoubtedly contributed to the relatively slow rate of return to that State during the first 6 months after revocation of exclusion.

To counteract unreasoning prejudices against all persons of Japanese descent and correct the factual distortions about War Relocation Authority activities which had been disseminated by hostile West coast organizations and newspapers, the Authority undertook a positive program of public information in the far western area several months before revocation of exclusion. Working mainly through and in cooperation with civic clubs, church groups, and similar organizations, War Relocation Authority field officers tried to reach as many people as possible with factual information about the agency's aims and procedures, the status and experiences of the evacuated people since evacuation, and especially the combat record of Japanese American soldiers. Pamphlets and bulletins, setting forth such information, were made available to groups and individuals upon request; explanatory talks were given before dozens of local forums and organizational meetings; motion pictures, dealing with the relocation program, and the Japanese American soldier, were shown; progress reports and other types of information were released to the press.

In this effort, information about American servicemen of Japanese descent proved particularly effective. The almost unparalleled combat record of the all-Nisei One-hundredth Infantry Battalion and Four Hundred Forty-second Regimental Combat Team, the long list of Nisei casualties, and the impressive array of their battle decorations brought home more forcibly than anything else the fact that Japanese Americans are capable of the highest kind of loyalty to the United States and that the families in relocation centers have sacrificed equally with other American families in the winning of the war.

When the pattern of terrorism in California became plainly apparent toward the end of March, a definite system of reporting incidents to the State and local law enforcement officials and to the press, both locally and nationally, was instituted. On May 14, the Secretary of the Interior finally issued a strongly worded public statement condemning the terroristic elements and calling for more vigorous local law enforcement. Approximately 2 weeks later the Secretary took occasion at a press conference to denounce a California justice of the peace who had suspended sentence upon a man convicted of shooting into the home of a returned evacuee. By these means, the public both on the West coast and throughout the Nation was made gradually aware of the insidious manifestations of racial prejudice in California and of the less violent forms of opposition both there and in the Northwestern States. Before the end of June scores of newspapers in all sections of the country had brought the issue of West coast terrorism sharply into focus and had aroused a widespread demand that the returning evacuees be accorded fair and decent treatment.

As the period ended, there were encouraging signs that this heightened public awareness of the issue was having a salutary effect. The tone adopted by many of the opposition groups was becoming progressively milder and more defensive, while several organizations of West coast citizens friendly to the evacuees were growing increasingly active and outspoken. Most significant of all perhaps, the incidents of terrorism dwindled sharply, both in frequency and viciousness, almost immediately after the Secretary's two public statements. In fact, there was no incident of major importance between the Secretary's second statement and the end of the fiscal year.

Financial Assistance for Resettlers

On the day after announcement of revocation the War Relocation Authority sent to all evacuees, both in and out of centers, a comprehensive statement on the types of assistance that would be available thereafter for relocating families and individuals. Travel grants and transportation of personal properties, which had previously been extended only on a showing of need, were made available generally to all persons leaving the centers for relocation. Such assistance was also extended to those who had previously relocated outside the West coast area and who now wished to go back to their States of former residence. Additional grants, to cover the cost of subsistence while traveling as well as expenses during the transition period immediately after arrival at destination, were continued for those resettlers in actual need of such supplemental help.

At each center, however, there was a group of people who needed assistance over and above these types of aid in order to become satisfactorily reestablished in private life. This group included those whose family resources had been seriously depleted as a result of evacuation, unattached individuals who were incapable of complete self-support, and families without any prospect of adequate and continuing income. Early in the relocation program, the War Relocation Authority completed an agreement with the Social Security Board for cooperation on a program of financial assistance specifically designed to meet the needs of such people as well as those resettlers who might be faced with a sudden, unpredictable, short-range need for help. This program, actually administered by State and local public welfare agencies, was financed by funds made available to the Social Security Board by the War Relocation Authority.

Before revocation of exclusion, there were comparatively few applicants for assistance under this program among the relocating groups. As the more able-bodied, primary wage-earners left the centers in increasing numbers during 1943 and 1944, however, the so-called "dependency" cases loomed steadily larger in the residual population. Accordingly, when the ban was lifted and plans for closing centers were announced, the War Relocation Authority began almost immediately to intensify and broaden the arrangements which had previously been made for handling dependency cases. Since most of the dependent evacuees could qualify for continuing public assistance only in their States of former residence, first attention was given to working out a satisfactory referral procedure with State and local welfare agencies of the former evacuated area. At the centers staffs of trained welfare workers were geared up to the job of interviewing all families and individuals who had special problems of support, analyzing their needs, and advising them of the types of assistance for which they might be eligible. Case summaries prepared at the centers were transmitted through the War Relocation Authority field offices to the State and ultimately the local welfare agencies.

Although the procedure for handling dependency cases was somewhat slow and cumbersome at first, it was streamlined and speeded up considerably throughout the spring. By the end of June, most of the delays had been eliminated, and the War Relocation Authority was able to plan for the final closing of the centers with full assurance that no genuinely needy person would be left without adequate means of support.

Employment and Housing

Because of the widespread need for workers of nearly all types, relocating evacuees experienced comparatively little difficulty during the year in finding job opportunities consistent with their individual qualifications. The problem lay, rather, in finding enough evacuees to fill the jobs which were available.

On the West coast, however, the resettlers enjoyed somewhat less freedom of job selection than in other sections of the country. Governmental regulations continued to debar the evacuees from employment in coastal fishing or waterfront work, while one of the more important labor organizations of the region -- the International Teamsters Union -- adopted a policy of categorically excluding from membership all persons of Japanese descent except honorably discharged veterans. In a few cases individual labor union members resisted working on the same jobs or in the same shops with the returnees and even threatened to strike if the Japanese Americans were hired.

The most noteworthy case of this kind occurred in May at Stockton, Calif., where some members of the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union attempted to foment a strike in protest against the employment of three returned evacuees. This action was promptly repudiated as contrary to the union's policy both by the international president and by the head of the San Francisco local which had jurisdiction over the Stockton unit. The protesting members were swiftly suspended from membership and were told that the union would tolerate no racial discrimination. A strike was effectively averted and the evacuees continued on the job.

Housing was a problem for resettlers in practically all of the Nation's largest cities and was particularly acute in the metropolitan centers along the Pacific coast. Shortly after the opening of the West coast field offices, intensive efforts were made to encourage the establishment of evacuee hostels in that region similar to those which had previously been operating in other sections of the country. These hostels, usually operated by church groups or other organizations interested in assisting Japanese American relocation, were designed to provide temporary accommodations for resettlers until a more permanent type of housing could be located. Before the fiscal year ended, about a dozen had been set up in principal West coast cities. The War Relocation Authority actively assisted in their establishment by making surplus relocation center equipment -- such as bedding, cooking utensils, and the like -- available to the sponsors on a loan basis.

Both on the West coast and elsewhere the Authority assigned staff members at its principal field offices to work full time in helping resettlers to locate housing accommodations and marshaled every available resource to overcome this particular problem. By the end of June substantial progress had been made toward the ultimate goal of assuring at least temporary accommodations for every individual and every family group leaving the relocation centers.

CENTER MANAGEMENT

The job of operating emergency-built cities for displaced persons of Japanese descent has never been more than a temporary expedient in the War Relocation Authority program. From the time when the long-range policies of the agency were first formulated in the summer of 1942, the Authority has always looked forward to the day when the evacuation orders would be rescinded and the shelter of the centers would no longer be required. The War Department's announcement of December 17, restoring freedom of movement throughout the United States to the great majority of the evacuees, eliminated in one stroke the center's chief reason for continued existence.

The revocation order did not, however, automatically transport the thousands of center residents to their chosen destinations, and it did not solve overnight all the manifold problems involved in dissolving these complex wartime communities. In order to prevent a chaotic mass movement and allow for individualized relocation planning and assistance, a spaced-out program of center closing was obviously essential. After careful consideration of factors such as transportation, available housing, and employment opportunities, the Authority decided that no center could be closed on a sound basis in less than 6 months but that all (except Tule Lake) should be closed within a year.

Because of the greatly increased emphasis on relocation preparations and the need to keep center management problems at a minimum, a policy was adopted immediately after revocation governing visits that might be made back to the centers by previously relocated evacuees. At first, such visits were permitted only for purposes of completing family relocation plans or for emergency purposes and only with the advance approval of the appropriate War Relocation Authority field office. Later the advance approval requirement was eliminated, and each relocated evacuee was permitted a maximum of 30 days for visiting at the centers without regard to the purpose of the visit.

By the end of June all phases of center operations were well advanced toward final liquidation. Although there were still about 44,000 people to relocate and large amounts of Government property which eventually would have to be inventoried and processed through surplus property channels, the War Relocation Authority had every reason to believe that all centers could be closed by December and was contemplating the definite possibility of closing some at an even earlier date.

Construction and Maintenance

Revocation of the exclusion order brought immediate reduction of the construction and maintenance operations to a minimum, in all centers except Tule Lake, where it was necessary to complete a considerable program of buildings already under construction or planned. Likewise maintenance was pared down to the minimum consistent with efficient operation. By the use of lumber and other materials released through cancellation of many center construction projects, sufficient stock was available for all construction and maintenance, and the building of boxes and crates for the freight of relocating evacuees, without ordering new stocks. This was made more effective by the interchange of materials between the different centers.

Agriculture

During the first half of the fiscal year the agricultural program was in full operation, in accordance with the policy of producing as much of the food needed for the evacuees as possible. But with the announcement of the closing date for the eight relocation centers an almost complete reversal was made. No crops were planted in the spring of 1945 with the exception of Poston and Gila, where vegetables could mature and be harvested by June 30. No additional beef cattle or poultry were purchased and the hog breeding program was discontinued. A program for the orderly fattening and slaughtering of the livestock on hand was put into effect. By the close of the fiscal year most of the livestock at the centers had been consumed.

Community Government

Sponsored by the Community Councils of seven centers, an all-center evacuee conference was held in Salt Lake City in February. Approximately 30 delegates met for a week, discussing problems affecting the evacuee as a result of the opening of the West coast and announcement of center closure. The delegates prepared and approved a letter to the Director of the Authority requesting reconsideration of center closing and submitted a list of recommendations to facilitate resettlement and rehabilitation of those relocating. Although the Authority did not modify its policy on center closing, it gave careful consideration to the other recommendations of the conferees and instituted a number of procedural changes along the lines recommended.

Felonies, misdemeanors, and violations of administrative regulations decreased in all centers, and the general crime rate was small, compared with national rates.

Business Enterprises

Evacuee-operated business enterprises in the centers generally were in excellent financial condition at the close of the fiscal year, with assets on May 31, listed at $1,237,369, or 16 percent lower than 1 year previously. Inventories were reduced during the fiscal year from $872,000 to $429,000 and the cash balance increased from $441,000 to $666,000.

Education

With the end of a vigorous 3-year school program in the centers set to coincide approximately with the close of the fiscal year considerable readjusting was necessary. School enrollment on the elementary, secondary

and nursery school levels showed a drop of 2,780 during the

year. The elementary and secondary enrollment at the beginning of the

year was 18,772, and at the end of the year 16,399. The nursery

school enrollment dropped from 1,928 to 1,521. A major part of

these declines was the result of relocation. The records of pupils were

checked to insure that all outstanding requirements would be met.

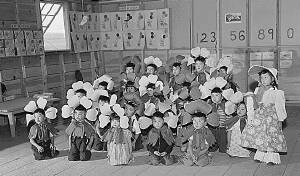

[PHOTO: "Clever costumes worn by the Nursery school children during the

labor day celebration." (Tule Lake, 09/07/1942)]

and nursery school levels showed a drop of 2,780 during the

year. The elementary and secondary enrollment at the beginning of the

year was 18,772, and at the end of the year 16,399. The nursery

school enrollment dropped from 1,928 to 1,521. A major part of

these declines was the result of relocation. The records of pupils were

checked to insure that all outstanding requirements would be met.

[PHOTO: "Clever costumes worn by the Nursery school children during the

labor day celebration." (Tule Lake, 09/07/1942)]Medical Care

During the year there was a marked decrease in the activities of the maternity service as compared with that of the previous year, accounted for largely by the departure of a great many young married people. Total births were 1,745; deaths 541.

When the exclusion order was lifted, there were 700 patients under War Relocation Authority's general custodianship in West coast hospitals, including approximately 250 tuberculosis patients hospitalized there prior to evacuation; 108 mental cases transferred to institutions in their States of legal residence, following commitments from centers, and the remainder, chiefly mental patients hospitalized over a long period. Arrangements were made as of June 30, 1945, for discontinuance of financial responsibility for hospitalization for 343 patients at approximately $900 per day.

A January survey showed there were 190 tuberculous patients in the various center hospitals who would need long-time sanitorium care, and a gradual transfer of these patients to the west coast was begun in the spring. At the same time individual interviews were held with over 200 tuberculous patients in west coast hospitals and reports of these interviews were sent to the appropriate centers in order to further relocation by correlating the plans of the patients with those of their immediate family members.

Fire Protection

With millions of dollars of value and thousands of buildings under their guardianship, fire protection crews at the centers established an enviable record of only 256 fires during the year, with a total loss in buildings and contents of $37,652, of which $25,310 was Government property and $12,342 private property. Granada center recorded only 10 fires; Poston with the greatest number had 48. Manzanar accounted for $19,264 of the total loss of which $19,051 resulted from the burning of three Governmental warehouses. The smallest loss at any center was $170 at Central Utah.

ADMINISTRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Administrative aspects of center closures involved huge physical assets which must be accounted for and disposed of in an orderly manner. Teams composed of accountants and property experts were sent into the centers where all property records were being put in order, as the fiscal year closed. Surplus properties were listed and a conservation program was adopted which entailed an exchange of materials and supplies between centers. Under this procedure things needed in each center were listed, and where these needs could be filled from the surpluses of other centers, transfers were effected.

Procedures for mess operations were overhauled and a policy adopted that would require the closing down of a block mess hall when the population in a block dropped to 125 residents. This resulted in a considerable saving of manpower and supplies, as many blocks throughout the various centers fell within the scope of the closing order. As a further conservation measure, food stocks which had been carried on the basis of a 60 to 90 day supply, were reduced so that quantities on hand were sufficient for only 20 to 30 days.

A procedure was also developed for the final disposition of all War Relocation Authority records, and the schedule which was recommended to the National Archives and the Congress was given the stamp of approval, and put into effect.

Among other problems which the War Relocation Authority faced during its liquidation period was the question of what would happen to its hundreds of civil service employees. In an effort to find an answer, a personnel survey was conducted in the spring of 1945 to determine possible placement of staff members with other Government agencies. On July 1, 1944, there were 2,284 employees, 2,015 of whom were stationed in the field, while 269 staffed the Washington offices. On June 30, 1945, the total employment was 2,436, an increase of 152, as the relocation program was being developed into its final phases. Most of this increase was in the field, where the total reached 2,154, with 282 in the Washington office.

LEGAL DEVELOPMENTS

Litigation of vital concern to the evacuees, both in and out of the centers, was spread on the records during the year.

On December 18, the United States Supreme Court handed down decisions in the Fred Korematsu and Mitsuye Endo cases. In the former, the legality of the evacuation orders was sustained. In the latter the court held that the War Relocation Authority had no authority to detain and control the movements of citizens who were concededly loyal to the United States. Although the War Relocation Authority in anticipation of War and Justice Department assumption of responsibility for security measures had been shaping its policies toward elimination of its leave clearance requirements in any event, the Endo decision made it unmistakably clear that detention of citizens solely on the grounds of race or ancestry could not be sustained before the courts.

Land laws aimed at alien Japanese began to crop up in various States. The Oregon Legislature adopted a law making the possession or ownership of land by Japanese and other aliens ineligible for citizenship a criminal offense, and amending the rules of evidence for the trial cases arising under the State alien land law. A proposed Colorado constitutional amendment to authorize restrictions on ownership of land by aliens failed in a referendum in November. In California, a referendum petition for an amendment to the State alien land law to extend it to "dual" citizens as well as aliens ineligible for citizenship and to its ownership of watercraft as well as land failed for lack of a sufficient number of signatures. This same amendment was introduced in the State legislature at its session which closed in June, but failed to pass. Law enforcement officials in California instituted 28 civil suits to forfeit to the State land alleged to be held by Japanese aliens and the State of Washington instituted 13 similar civil suits.

SEGREGATION CENTER

As it became increasingly apparent that the West coast exclusion would eventually be rescinded and War Relocation Authority leave regulations simultaneously abolished, plans were developed for setting up relocation machinery at the Tule Lake Segregation Center. Under regulations of the Western Defense Command, it was anticipated that quite a large number of these evacuees would be eligible for resettlement on the west coast as well as elsewhere in the United States.

A policy was adopted for Tule Lake similar to that in effect for other centers and by the time the ban was lifted on January 2, the administration was ready. Prior to this time there had been only slight interest in relocation, but in January inquiries began to trickle into the newly established relocation office in the center. The first person to relocated from Tule Lake since it had been designated as a segregation center was a young man who departed for Minneapolis late in the month.

In the period between that time and the close of the fiscal year, 140 persons relocated directly from Tule Lake to outside communities. In addition, approximately 400 residents of Tule Lake who were out on seasonal leave effected permanent departures during this period, or were institutionalized outside, so that a total of more than 500 actually relocated between January 2 and June 30. The population remaining as the fiscal year closed was 17,454.

The fiscal year at Tule Lake got away to a rather turbulent start, with the murder on July 2 of the evacuee manager of the Business Enterprises. This was apparently the culmination of a feud between those evacuees who were willing to cooperate with the administration and those who were not. As a result of the stabbing, the board of directors and all key evacuee personnel of the cooperative resigned. Before the end of July the entire evacuee police force also had resigned, as the investigation into the murder became more intense. The murder was never solved, and the police department was reorganized as the Colonial Peace, to carry on. A reorganization of the Cooperative was also effected, and by the end of July the Business Enterprises were again functioning satisfactorily.

Twenty-seven Nisei were arrested in July, charged with failure to report for preinduction physical examinations, but at their trial at Eureka, Calif., the charges were dismissed when the court held that Selective Service did not apply to residents of Tule Lake, since it was a segregation center. Also in this month 16 men held in the Stockade, where the more belligerent were confined, went on a hunger strike which lasted 10 days.

There followed a period of agitation for "resegregation" by the pro-Japanese group, which began to promote Japanese culture through three societies, Sokuji Kikoku Hoshi Dan, for older men; Hokoku Seinen Dan, for younger men and Hokoku Joshi Dan for women. These societies sponsored early morning marching formations by their members and engaged in other pro-Japanese rituals intended to develop more strongly the Japanese pattern of living. These practices subsided, however, and much of the resegregation agitation also, with removal of 56 of the leaders to the internment camp at Crystal City, Tex.

In December the Department of Justice completed hearings on another 56 men who had asked expatriation, and these, together with 14 aliens, were transferred to the internment camp at Santa Fe, N. Mex. They left Tule Lake on December 28, 10 days after announcement of the lifting of the West coast ban. This announcement and the accompanying announcement of the liquidation of the other centers had a dampening effect on any demonstration by the population. In all, 1,416 persons were removed by the Justice Department from the Tule Lake center to internment camps during the fiscal year.

EMERGENCY REFUGEE SHELTER

On June 30 the Emergency Refugee Shelter at Fort Ontario, Oswego, N.Y., completed its first fiscal year under the administration of the War Relocation Authority, which was first designated for this responsibility on June 9, 1944. While plans were being made to receive the European refugees as the 1944 fiscal year closed, the War Relocation Authority did not actually assume custody of the Fort Ontario grounds until July 30. Six days later, on August 5, the refugees arrived at the Shelter where housing had been prepared for them on the old fort grounds.

In the group were 982 persons ranging in age from infants to octogenarians, representing 18 nationalities. The largest national groups were 367 from Yugoslavia; 244 from Austria; 149 from Poland; 94 from Germany and 41 from Czechoslovakia. Others were from Belgium, Bulgaria, Danzig, France, Greece, Holland, Hungary, Libya, Rumania, Russia, Spain, and Turkey.

With so many nationalities represented the Administration was faced with complex problems caused by language, geographic and cultural differences. However, a plan of community organization was set up similar to that which had been operating in the relocation centers, with the exception of schools. Arrangements were completed on September 1, with school authorities in the adjacent town of Oswego, whereby the children of the refugees would be accepted on the same basis as American children. With the opening of classes, 189 of these children were enrolled.

Although the refugees were brought into the United States outside immigration quotas and were required to sign an agreement which stated that they understood they were to return to their homes after the war, it soon became apparent that the majority had no desire to return, that many had close relatives in the United States, and that most sections of liberated Europe were in no position to receive them. The most feasible alternative was to develop procedures under which those who desired to remain in America could be admitted under quotas which had not been filled since the start of the war. Early in the spring the War Relocation Authority began exploring the possibility of such a program, with the Departments of State and Justice, but no definite conclusions were reached by the end of the fiscal year. Meanwhile, members of the subcommittee of the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization conducted hearings at the Shelter on June 25-27, inclusive, to determine the possibility and advisability of extending immigration status to the Shelter residents. As the year closed, this subcommittee had not yet announced its findings.

During the year there were 14 permanent departures from the Shelter. One person left on February 28 for the Union of South Africa, and 13 others returned to Europe on the Gripsholm on May 30. There were 10 deaths and 11 births during the year, leaving a net population of 969 as of June 30.

On June 6, the over-all responsibility for the Shelter program was transferred by order of the President from the War Refugee Board to the Department of the Interior.

CONCLUSION

As the War Relocation Authority approached the end of its unique experience in caring for a displaced racial segment of the American population, it becomes somewhat easier to evaluate that experience in proper perspective and to derive from it certain basic recommendations for the future.

First, the War Relocation Authority earnestly hopes that the United States will never again be faced with a similar problem.

Second, the Authority recommends strongly against putting displaced people in camps except for limited periods and under emergency conditions, such as natural catastrophe, where there is no feasible alternative.

Third, this agency has learned the grave dangers that lie in generalizing about a whole group of people and restricting their movements on the basis of such generalization. It believes deeply that no resident of this country should be detained or moved against his will merely because he is a member of some group. All actions of this kind should be based on painstaking examination of the person's individual record.

Fourth, the War Relocation Authority is under no illusions that it has completely solved all problems of the evacuated people of Japanese descent. After the last War Relocation Authority field office is closed, there will still be a tremendous job for American democracy in helping these people to become satisfactorily readjusted and in safeguarding their rights against the poison of racial discrimination. But this is a job which can be done most effectively by private organizations and individuals working close to the problem in the scores of communities where the resettling evacuees have made their homes. For more than 2 years the Authority has been encouraging such groups to assume an increasing measure of responsibility for evacuee adjustment and for protection of evacuee rights. It now looks forward to the termination of its own official life with full confidence that the work of fitting the evacuated people back into the main stream of our natural life will be carried forward with energy and zeal.

-- Table of

Contents --