Legal and Constitutional Phases

of the WRA Program

United States Department of the Interior

J. A. KRUG, Secretary

War Relocation Authority

D. S. MYER, Director

PART I

THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF EVACUATION AND DETENTION

The evacuation of 112,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, their continued exclusion from the West Coast from the summer of 1942 until January of 1945, and their detention for varying periods of time in assembly centers and relocation centers, inevitably raised extremely grave questions as to the consistency of such a program with the requirements and the prohibitions of the Federal Constitution. The fact that two-thirds of the evacuees were citizens of the United States by birth sharpened these very grave issues.

Did the Federal Government have constitutional power to evacuate all these people from their homes and their jobs, and compel them to leave the West Coast? Even the women and children? Even those who were citizens? Could it do so without charging any of them with having committed any crime, and without any trial or hearing? Could the Government follow the order to vacate the the West Coast with enforced detention in an assembly center? Could the Government thereafter, without consulting the evacuees, transport these people from the assembly centers to relocation centers under military guard and thereafter incarcerate and forcibly detain the evacuees in the relocation centers? What about the constitutional rights, in particular, of those evacuees who were citizens of the United States and who insisted throughout these activities that they were patriotic, and loyal to the United States, and willing to fight in the armies of the United States to prove that loyalty?

Not all the officers and agents of the United States Government who played responsible parts in the evacuation and detention were seriously troubled by these questions of constitutional power and constitutional right. Many, however, were deeply concerned. It is the answers to these questions provided by those who were concerned -- and, later, by the Supreme Court of the United States -- that this report will discuss.

There were two important reasons why the administrators of the WRA program felt compelled to think through these searching questions of constitutional authority. In the first place, the evacuees were deeply shocked by the fact of evacuation, and unable to determine what implications the evacuation carried for their future residence in the United States as citizens or as lawfully resident aliens? WRA had to provide to the evacuees and to itself answers to these questions that would provide a rational and moral basis for its relocation program. In the second place, WRA had to be prepared to answer these same questions when propounded by Congressional investigating committees, by groups attacking the relocation program, by citizens whose support it sought to mobilize, and by litigants in the courts.

The many constitutional issues can be reduced to three basic questions:

1. Was the evacuation valid under the Constitution?

2. Was detention in assembly centers and relocation centers valid under the Constitution?

3. If it were to be assumed that the original evacuation was constitutional. because it was compelled by an overriding military necessity, how long did the military necessity continue to be sufficiently grave to justify continued exclusion; did such continued exclusion remain valid all the way through until December 1944 when the exclusion orders were finally revoked?

Was Evacuation Constitutional?

It is radically important to make a distinction at the outset between the question whether a given governmental action was valid under the Constitution and the question whether that action was wise or proper. A governmental action -- an increase in tariff schedules, the establishment of price control or consumer rationing, the prohibition of gambling, the evacuation of all persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast, or whatever -- may be both a wise policy and a constitutional policy, or it may be a wise policy but not one permitted under our Constitution, or it may be an unwise policy but one that is permitted under our Constitution, or it may be a policy that is both unwise and prohibited by our Constitution. This would seem to be an elementary idea, hardly worth emphasizing, but for the fact that, again and again, persons convinced that the mass evacuation was unwise, unsound, and unfair, leaped unthinkingly to the conclusion that a policy of which they so strongly disapproved as unwise must necessarily, therefore, be also unconstitutional.

The reasoning which led the Department of Justice and the Office of the Solicitor of WRA to the conclusion that the evacuation was within the constitutional power of the Federal Government -- and which was later adopted by a majority of the Supreme Court of the United States1 may be summarized in the following numbered propositions:2

1. The question to be answered is: Was the mass evacuation within the power of the Federal Government in the spring of 1942, when it was decided upon and put in effect? It is the situation in existence at that time that is controlling. (A later change in the situation might require some new governmental act, but would not affect the validity of the earlier evacuation.)

2. The Federal Constitution confers upon the Federal Government the power to wage war. This is an extremely broad power. It is "the power to wage war successfully." It includes the power to interfere very greatly with the lives and free movement of citizens and alien residents where the interference is a necessary step in waging war.

3. In the present case the President authorized the evacuation by Executive order.3 Subsequently the Congress "ratified and confirmed" that Executive order by enacting a statute which provided criminal penalties for violation of military orders issued pursuant to the Executive order.4 The evacuation was authorized, therefore, by the President and the Congress acting together. It is not necessary for the Court to determine whether the evacuation would have been valid if ordered by the President, solely under his powers as President, without Congressional concurrence.

4. The crux of the issue is: Can the Government show that the mass evacuation was a military necessity -- that is, that the evacuation was a necessary step in the program of waging the war against the enemy? That the evacuation was such a military necessity will be demonstrated immediately below -- but first, we must introduce into the argument at this point an important consideration: in determining whether the evacuation was in fact a military necessity, the Court will not substitute its own final judgment on the facts for the judgment made by the responsible military commander who carried authority and responsibility for making the decision at the particular time and in the particular circumstances. The Court will decide, not whether the judges would have ordered the evacuation if they had been the responsible military commanders at that time and had had available to them the facts that were available to the actual military commander, but only whether the facts available to the military commander were such that he could, in an honest and reasonable exercise of judgment, conclude that the evacuation was a military necessity.

5. The facts available to the responsible military commander in the spring and summer of 1942, which were sufficient to enable him to conclude, reasonably and honestly, that mass evacuation was a military necessity were the following:

A. The military situation on the West Coast in the spring and summer of 1942 was grave. The Japanese had successfully attacked the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor and had very seriously damaged the United States Fleet. Rapidly thereafter the Japanese army invaded Thailand, sank the British battleships Wales and Repulse, captured Guam, Wake Island, Hong Kong, Manila, Singapore, the Netherlands East Indies, Rangoon, Burma, and then the whole of the Philippines.6. A responsible military commander must guard against probable dangers and possible dangers, and not alone against dangers certain to develop, to the extent that his available forces permit.

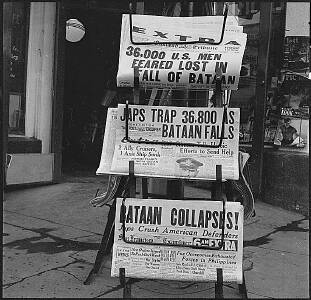

"As Bataan fell, as recorded in these newspapers of April 9, 1942, evacuation of residents of Japanese ancestry was already under way. Hayward, California."

On February 27 the Battle of the Java Sea resulted in a naval defeat to the United Nations. On June 3 Dutch Harbor, Alaska, was attacked by Japanese carrier-based aircraft, and on June 7 the Japanese gained a foothold on Attu and Kiska Islands. Once in February and once in June 1942 the coasts of California and Oregon, respectively, had been shelled. Following the Pearl Harbor attack the Japanese had a naval superiority of three or four to one in the Pacific Ocean. The Army and the Navy believed that it was of the utmost military importance to prepare against an invasion of the Pacific Coast by Japan.

B. The threat of invasion and attack of the Pacific Coast by Japan created fear that the enemy might use the so-called fifth column technique of warfare.

C. War facilities and installations were concentrated on the West Coast to such an extent as to make it an area of special military concern. Important Army and Navy bases and a large proportion of the Nation's vital war production facilities were located in that region.

D. Approximately 112,000 persons of Japanese descent resided in California, Washington, and Oregon at the time. There was considerable prejudice and hostility toward these resident persons of Japanese descent, both citizen and alien, on the part of the rest of the population, expressed in discriminatory State legislation, discrimination in employment, severely limited social intercourse, and considerable physical segregation.

E. About one-third of the persons of Japanese ancestry were aliens, because barred by the Federal naturalization laws from becoming citizens.

F. It was widely believed that the resident persons of Japanese ancestry felt close ties of kinship and sympathy with Japan. This belief was in part based upon the maintenance of Japanese language schools, the existence of many Japanese cultural societies, the practice of Japanese parents of sending their American-born children in their early years to Japan for some years of residence and education, so that approximately 10,000 Kibei were then living on the West Coast, the belief in and practice of Shintoism by an unknown number of the group, and the fact that many of the parents had taken affirmative steps to secure or protect dual nationality in both the United States and Japan for their children.

G. It was widely believed that there existed among the persons of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast an unknown number of potential saboteurs, who could not be identified, but would rise to aid an invading Japanese Army, if such an invasion took place.

H. It was generally feared on the West Coast that the latent hostility toward persons of Japanese ancestry might produce civil disorder and local violence.

7. Mass evacuation of all persons of Japanese ancestry would eliminate the danger of their engaging in sabotage and espionage in aid of invasion by the Japanese Army and Navy, at the price of compelling 112,000 people to remain away from their homes during the period of invasion, without seriously disrupting war production in the evacuated area.

Considering these propositions cumulatively the Government took the position that the responsible military commander could reasonably and honestly have decided, in the spring and summer of 1942, that such mass evacuation was a military necessity. A majority of the Supreme Court agreed with this view and sustained the constitutionality of the evacuation in its decision in the Korematsu case.5

A thoughtful person considering the argument thus far presented will still entertain some unanswered questions. In the first place, was this not an evacuation of an entire racial group because of their racial difference, and if so, how can it be constitutional for the Government to sanction race prejudice and race hate with a mass evacuation? The Government admitted in its briefs in the Supreme Court that unless the fact of racial difference can be shown to have a special effect on the military problem, the evacuation of a racial minority merely because of that racial difference would violate the constitutional rights of the evacuees. The argument summarized above, however, indicates that the persons of Japanese ancestry were involved in a total complex of circumstances that created a danger of sabotage and espionage in aid of an invading Japanese Army. It was, therefore, military necessity, and not the racial difference, that created the constitutional power to evacuate.

This leads to another question: Why was there no mass evacuation from Hawaii where persons of Japanese ancestry bulked so much larger in the total population, and does not the failure to evacuate from Hawaii cast doubt on the argument of military necessity? A sufficient answer may lie in the fact that the whole of Hawaii was placed under martial law. The Army had thus gone farther in Hawaii to guard against sabotage and espionage than it was prepared to go on the West Coast of the Mainland, and the declaration of martial law may well have made the expedient of evacuation of part of the population unnecessary. Further, a commanding general must consider the price he will have to pay for each protective measure he may wish to undertake. The price in reduced war production on the West Coast of the United States would be small; that price in Hawaii would be disproportionately large. The danger may therefore well have been considered sufficient to justify the decision to evacuate on the West Coast while relying on the defenses of martial law in Hawaii.

Why, then, were not Germans and Italians evacuated from the Pacific Coast -- or from the East Coast as well? Here, again, the commanding general needs always to consider the balance of forces and factors. It was the Japanese Army, and not the German or Italian, that threatened invasion of the West Coast. No army was considered at any time during the war seriously to threaten an invasion of the East Coast. The size of the population to be evacuated, if Germans and Italians were to be evacuated would, also, make the protective measure more costly and hazardous than the anticipated danger.

These are the considerations which the Government and the Court needed to weigh when considering the constitutionality of evacuation. Every citizen must likewise weigh them. Where unwise governmental action is advocated, it is important that it be challenged and defeated, or repudiated if already performed, on the ground that it is unwise, and through regular democratic processes. To condemn an unwise action by denying its constitutionality is to run the risk of weakening the National Government so that it may become incapable of taking similar action under circumstances where everyone may agree it has become wise.

This, of course, is not to say that all those who advocated the mass evacuation were animated by considerations of military necessity. Many advocated it because they were blinded by race hate and many for petty, selfish reasons. Also, many were easier to convince of the military necessity because racial prejudice had prepared their minds to believe the worst. Part of the price of prejudice which a democracy must always pay is the power of prejudice to blind the democracy to what the facts of necessity may be and to the courses of action that may be open to it.

These, at any rate, were the arguments that led WRA, and the Federal Government as a whole, to assert the constitutionality of evacuation. This position makes irrelevant the fact that none of the evacuees were charged with crime or were given trials or hearings. The ground of evacuation was not individual guilt but the necessity for mass evacuation to guard against potential danger from a possible minority, the members of which could not be readily identified.

Was Detention Constitutional?

The leave regulations and the relocation program of WRA have been described in detail in other final reports of the Authority and need not be restated here.6

In baldest outline, this was the procedure: All the evacuees were detained, first in assembly centers and then in relocation centers, until certain basic information could be secured concerning them, and checked against the files of the intelligence agencies of the Government, so that a judgment could be made as to each adult evacuee that he was or was not potentially dangerous to the internal security of the country if released during the war. (In practice, however, many were released for seasonal agricultural labor even before checking of their records was completed.) Those evacuees who were found, on the basis of this screening, to be "nondangerous" were then eligible to leave the centers as soon as WRA was satisfied that they had a job or other means of support, and that the community into which they wished to go could receive them without danger of violence. (In fact, WRA also required each departing evacuee to agree to keep it notified of each change of address, but no evacuee was ever detained for refusal to make this agreement and no action was ever taken against the many who ignored the agreement. This was understood tacitly to be a requirement born of administrative convenience and not of internal security, and was never intended to qualify the right to leave a center.) Those denied leave clearance were to remain in detention.

Whether this kind of detention is valid in the case of the alien evacuees is a question that can be answered easily and may therefore be disposed of first. It is quite clear that Congress has conferred upon the President7 the power to restrain and detain alien enemies in time of war in such manner as he may think necessary. The constitutionality of that authorization is universally conceded.

In the case of the citizens, however, this detention program raises three distinct questions:

1. Did the Government have constitutional power to detain all the evacuees while they were being sorted to determine which might be dangerous to internal security if released?

2. Did the Government have constitutional power to detain admittedly nondangerous evacuees until the Authority was satisfied that they had a means of support and that the community into which they wished to go could receive them without danger of violence?

3. Could the Government constitutionally detain those evacuees deemed potentially dangerous, and for how long?

Detention Pending the Sorting

If the evacuation were to be considered to be unconstitutional then, of course, any variety of postevacuation detention also falls as without constitutional support. Assume, however, that the evacuation itself be deemed constitutional, could not the Government have said to the evacuees as they stood on the eastern border of the evacuated area, "Go wherever you wish in the United States, but you may not return to the excluded area until further word"?

It is difficult, in the calm aftermath of a securely-won war, to recall the worried concern, the heightened sense of danger, the volatile emotional atmosphere that were the inescapable facts of life during the months when the enemy was in the ascendancy and the Nation was grimly getting ready to launch a hoped-for offensive. Detention was a policy which the responsible officers of WRA decided upon reluctantly, out of a conviction that no other course was administratively feasible or genuinely open to them. The agitation for mass evacuation had repeatedly asserted that West Coast residents of Japanese ancestry were of uncertain loyalty. The Government's later decision to evacuate was widely interpreted as proof of the truth of that assertion. Hence, a widespread demand sprang up immediately after the evacuation that the evacuees be kept under guard, or at the very least, that they be sorted and that the dangerous ones among them be watched and kept from doing harm. In these circumstances it was almost inescapable that the program administrators should come to the conclusion that if the right of free movement throughout the United States was to be purchased for any substantial number of the evacuees, the price for such purchase would have to be the detention of all the evacuees while they were sorted and classified, and then the continued detention of those found potentially dangerous to internal security. The detention policy of WRA was born out of a decision that this price would have to be paid, that it was better to pay this price than to keep all the evacuees in indefinite detention, and that to refuse to pay this price would almost certainly mean that the prevailing popular fear and distrust could not be reasoned with and could not be allayed.

The Supreme Court was never presented with an opportunity to pass upon the validity of the mass detention pending sorting. Had the question ever been presented to it for decision, the Court would undoubtedly have been disturbed by the length of time it took to complete the sorting. A detention of a few weeks, perhaps a detention of 4 or 5 months considering the size of the total group, it should not have been too difficult to sustain under the circumstances. Although the sorting, in fact, took the better part of 2 years, it is true that any evacuee who for any reason was particularly anxious to leave early, could arrange to secure priority consideration of his request and only a very few cases were detained for more than 8 to 10 weeks because of the processing of security clearance.

Before we state more fully the legal argument in defense of such detention, let us consider the next type of detention involved since many of the same considerations apply to both.

Detention for Employment and Community Acceptance

Before they could receive permission to leave the center, those who received leave clearance needed also a job or means of support, and needed to be headed for a community which WRA believed willing and capable of accepting evacuees without danger of violence. Was such detention valid?

These conditions to departure -- that the evacuee shall have been found to be nondangerous to internal security, that there shall be "community acceptance" at his point of destination, and that he shall keep the Authority notified of his changes of address -- represented, in fact, the heart of the relocation program. They were designed to make planned and orderly what must otherwise have been helter-skelter and spasmodic.

The very fact that 112,000 people had been evacuated -- and evacuated under a cloud -- created for the Government a special resettlement problem. Had the evacuees been merely innocent victims of a major flood, routed from their homes by sheriffs and deputies and brought out of the danger zone, the Government would inevitably have been compelled to take appropriate action to reestablish the flood evacuees without serious disruption of the social fabric. It might well have had to detain all the flood evacuees until they were inoculated against disease and until they were provided with the basic essentials, and until they satisfied the authorities that they had some place to go for immediate shelter. The Government might well have had to provide temporary shelter for thousands of such evacuees and, if so, would have had to regulate the entries and departures from such temporary refuge. The problem was much more acute in degree in the case of these wartime evacuees. If the constitutionality of the evacuation itself be assumed, the situation that was inevitably created by the evacuation does of itself give rise to new problems which Government must undertake to solve by appropriate means.

Thus, the conditions attached to departure from the centers enabled a sifting of a possibly questionable minority from the wholesome majority whose relocation it became the principal object of WRA to achieve. These restrictions enabled WRA to prepare public opinion in the communities to which the evacuees wished to go for settlement, so as to avoid violent incidents, public furor, possible retaliation against Americans in Japanese hands, and other evil consequences. The leave regulations "stemmed the flow"; they converted what might otherwise be a dangerously disordered flood of unwanted people into unprepared communities into a steady, orderly, planned migration into communities that gave every promise of being able to amalgamate the newcomers without incidents, and to their mutual advantage. The detention, in other words, was regarded as a necessary incident to this vital social planning.

During the whole of 1943, WRA fought for the leave clearance and relocation program, not against those who charged that this was an unconstitutional interference with the rights of the evacuees, but against those who argued that only wartime internment of all the evacuees could adequately safeguard the national security. During 1944 the resettled evacuees were increasingly winning acceptance, and the military situation was steadily improving for the United Nations, and public fears were slowly being quieted, and the Nisei military exploits were gradually becoming known, and the voice of conscience was slowly growing louder in the land, and criticism then began to direct itself against the continuation of the detention of those found eligible to leave. During this period, also, detention of those eligible to leave became more and more a matter of form rather than of substance. WRA had by now succeeded in laying the groundwork for relocation throughout all parts of the country other than the evacuated area, so that the requirement of community acceptance was satisfied in advance for all evacuees. Similarly, WRA was equipped to find a job for any evacuee who needed help in securing one, so that the requirement of employment or other means of support was satisfied in advance for practically all evacuees. It is literally true that for the large majority of the evacuees there was no detention of evacuees in relocation centers during most of 1944 and subsequently, except in form and in theory. Any one whose record was satisfactory not only could leave on request but was assisted, urged and persuaded to depart. Relocation of those eligible to leave had by then become the objective to which much of WRA's appropriation and most of WRA's energies were directed. The assistance consisted of transportation to the place of destination with a small resettlement grant to tide the evacuee over the adjustment period. Special dependency cases received special assistance.

It was not until 1944 that the Supreme Court had an opportunity to pass on the question of the constitutional validity of detention of those evacuees who had received leave clearance until the requirements of job and community acceptance were satisfied. [penciled in: "of citizens who had received leave clearance this came about in the case of Ex parte"] In December the Supreme Court delivered its opinion in the case of Ex Parte Mitsuye Endo,8 a petition for the writ of habeas corpus filed on behalf of a young woman who had received leave clearance but who refused to indicate a destination other than Sacramento, California, from where she had been evacuated. No community in the evacuated area could satisfy WRA's requirement of community acceptance since the Army continued to exclude evacuees from returning to that area. Mr. Justice Black, speaking for the majority of the Court, decided that it was not necessary for the Supreme Court to determine whether such detention was constitutional because, said Mr. Justice Black, such detention was not authorized by Executive Order No. 9102 or any other Executive order or any act of Congress. Since Miss Endo, said the Court, was admittedly loyal to the United States and not endangering its internal security, her detention could not be said to be authorized by Executive orders which sought to guard the West Coast against sabotage and espionage. Mr. Justice Roberts dissented on the ground that the Congress and the President had specifically been informed of the kind of detention that WRA was enforcing, and had ratified and confirmed WRA's interpretation of Executive Order No. 9102 -- the President in a message to the Congress, and the Congress in appropriations made to WRA with knowledge of the details of the program to be financed with those appropriations. And, said Mr. Justice Roberts, as thus ratified and confirmed by the Congress, the detention of nondangerous persons is unconstitutional. All the members of the Court thus found themselves in agreement, although for different reasons, that Miss Endo must be ordered at once released. WRA immediately lifted its requirements of means of support and community acceptance.

The decision of the Court in the Endo case came 48 hours subsequent to the announcement by the Army that the exclusion orders were being revoked. The revocation of the exclusion orders was coupled with the termination of the leave regulations. Thereafter, with the exception of those detained by the War Department or the Department of Justice, nearly all of whom had by then been transferred to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, the evacuees were free to leave the centers at will. A short time later the military guards were removed and the Authority's program intensified its efforts to persuade the remaining evacuees to relocate.

Detention of Those Deemed Ineligible to Leave

The only aspect of the detention program which the Supreme Court was asked to pass upon was detention of those who, like Miss Endo, had received leave clearance. The Court never ruled on the validity of detaining all evacuees while they were being sorted nor on the validity of detention of those deemed ineligible to leave.

WRA took the position that it sought to detain those deemed ineligible to leave until after all those deemed eligible had been relocated. Such detention, it maintained, was necessary to build public acceptance of those found eligible to relocate. The detention was thus regarded as an essential step in the accomplishment of the relocation objective. Since the war ended before relocation of the eligibles had been completed, the Government never had to face the question of whether it could or would attempt to detain those deemed ineligible after the relocation objective had been fully achieved. In the period from December 1944 to February 1945 many of the detainees renounced their citizenship. After revocation of the exclusion orders, and on termination of WRA's sorting processes, the War Department and the Department of Justice assumed responsibility for determining who should remain in detention. Those Departments detained for a time most of the renunciants but released from detention all citizens formerly detained who had not renounced their citizenship. The revocation of the exclusion orders was thus followed before very long by the termination of the detention of citizens.

How Long was Continued Exclusion Constitutional?

The argument for the constitutionality of evacuation summarized above laid great emphasis upon the military situation that obtained in the winter, spring, and early summer of 1942. Clearly, as the military situation improved, as the danger of military invasion of the West Coast by the Japanese Army receded, and as the processes of sorting the evacuees into eligible and ineligible categories were completed, the arguments for the military necessity for the evacuation program became deeply affected. The exclusion orders were not revoked until December 1944. It seems clear to the point of certainty that the military situation had so far improved as to make continued exclusion no longer valid many months, and perhaps more than a year, before the exclusion orders themselves were finally revoked. It remains true, nevertheless, that the assignment of the precise hour when the military balance so far shifted that evacuation ceased to be a military necessity is a difficult task. The courts would understandably hesitate to substitute their judgment on such an issue for the judgment of the responsible military commanders. If the delay in revocation was longer than it need have been, it was not so much longer as it well might have been. The orders were revoked more than 6 months before the end of the war with Japan.

During the months prior to revocation of the exclusion orders, any relocated evacuee might have sought to return to the excluded area, and if physically interfered with by the Army might have sought to restrain such interferences in the courts on the ground that continued exclusion had ceased to be a military necessity and hence had ceased to be valid. It is a striking fact that not one such suit was filed although such return was a few times attempted and prevented.9

The Strategy for Litigation

In 1942 and early in 1943, while public feeling still ran strong and the military situation still looked dark, the Authority's lawyers believed that it was undesirable for cases testing the constitutionality of evacuation and of detention to be hurried to the Supreme Court. Decision on such complicated questions can be more soundly conceived when the atmosphere has been freed of the surcharged emotions generated by the dangers and tensions of war. The Authority, of course, could not and did not seek in any way to interfere with the freedom of evacuees to have recourse to the courts for redress of their grievances. But those evacuees or friends of the evacuees who sought the advice of the Authority were advised that the niceties of individual liberties would receive correspondingly fuller attention and protection as the Nation's crisis was passed, as the military situation improved, and as people generally were able to breathe more easily and think more soberly. This remained the advice of the Authority throughout the early period.

During what might be called the "middle period" the Authority advised that the time had come for free testing of these issues in the courts. It indicated its willingness to cooperate in the submission to the courts of well chosen "test cases" that would fairly and adequately present the issues for decision. It quickly became clear that the evacuees generally shunned legal conflict with the Government. Most of the evacuees apparently took the position that their future in the United States might be imperiled by large-scale litigation challenging the evacuation and challenging the detention that was a part of the relocation program. It is this fact that accounts for the failure to bring to the Supreme Court cases that would adequately have tested the validity of the various kinds and classes of detention discussed in this report.

Also during this middle period the Authority faced the question of revising its leave regulations to eliminate the requirement that an evacuee who had received leave clearance be possessed of a job or other means of support and be headed for a community willing to receive him. Opponents of the relocation program were still continuing a heated attack on the Authority, charging that the leave regulations were too lax and permitted too many people to leave the centers. The Authority would have welcomed a Court decision testing the validity of continuing to impose these requirements. The Endo case, referred to above, fortunately met part of this need. When the Department of Justice considered rendering the case moot, the Authority protested. The pendency of this case in the Supreme Court thus postponed for several months the necessity for deciding whether to eliminate these requirements from the leave regulations. In December of 1944 the decision in the Endo case eliminated these requirements, and the revocation of the rest of the leave regulations soon followed.

In the final year of the operation of relocation centers detention by WRA was no longer the issue to be tested. Now the issue became whether the Department of Justice had the legal authority to detain and deport evacuees who had renounced their American citizenship and who now sought to remain in the United States. A large number of suits to test this question were filed during 1945 in the Federal district courts, were consolidated for purposes of trial, and as this is written still await trial.

The convictions of the Authority on these legal issues may be here briefly summarized. It believed, as indicated above, that the evacuation, however unwise in fact, however unnecessary subsequent events proved it to be, was within the constitutional power of the Federal Government when undertaken and executed. It doubted from the beginning and never ceased to doubt the validity of the detention procedures. The detention procedures were adopted out of a conviction that no other course was administratively open or feasible, and that the administration must follow its only available course when the unconstitutionality of that course is no more than a matter of speculation and uncertainty. The detention of all the evacuees for a preliminary period pending their sorting and classification did not seem either too great a hardship for the evacuees to be subjected to or a course too difficult to defend in the courts. The detention of those deemed eligible to leave until they found jobs and until communities were prepared to receive them was deemed much more doubtful as to the constitutional validity but was also recognized to be a course pursued in the interest of the evacuees themselves and to be a course of action for which there was much to be said even on the issue of constitutional validity. The detention of those deemed ineligible to leave, the Authority felt, was an activity practically forced upon it and which it had no alternative but to pursue until the courts could pass on the issue.

1 Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944). See also Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943).

2 The argument is elaborated in the "Brief for the United States" filed by the Government in the Supreme Court of the United States in Korematsu v. United States, October Term 1944, No. 22. See also the "Brief for the United States" filed by the Government in the Supreme Court of the United States in Hirabayashi v. United States, October Term 1942, No. 870.

3 Executive Order No. 9102, March 18, 1942.

4 56 Stat. 173, 18 U.S.C.A. 97b.

5 Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944). See also the unanimous opinion of the Supreme Court in the case sustaining the constitutionality of the curfew regulations applicable to persons of Japanese ancestry, Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943). Mr. Justice Roberts dissented from the Court's decision in the Korematsu case on the ground that the detention in assembly centers and relocation centers, which is discussed below, was an inseparable part of the total evacuation program, that such detention was unconstitutional, and that therefore the evacuation itself was unconstitutional, the program as a whole being tainted with the invalidity of detention. Mr. Justice Murphy dissented on the ground that his independent re-examination of the facts satisfied him that there was no military necessity for the evacuation.

6 See "WRA -- A Story of Human Conservation", "The Relocation Program", and "Wartime Exile".

7 50 U.S.C. 21 - 24.

8 323 U.S. 283 (1944).

9 There was one attempt in late 1944 to test the validity of continued exclusion by an action to restrain interference with anticipated return. The War Department exempted the petitioners from the mass exclusion orders, thus precluding a decision on those orders, and issued individual exclusion orders which the Court refused to invalidate. Ochikubo v. Bonesteel, District Court of the United States, Southern District of California, Central Division, No. 3834-PH (1945).

-- Table of

Contents --