INVESTIGATION OF UN-AMERICAN PROPAGANDA ACTIVITIES IN THE UNITED STATES

HEARINGS BEFORE A

SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

SEVENTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS

FIRST SESSION ON

FIRST SESSION ON

H. Res. 282

TO

INVESTIGATE (1) THE EXTENT, CHARACTER, AND OBJECTS OF UN-AMERICAN

PROPAGANDA ACTIVITIES IN THE UNITED STATES, (2) THE DIFFUSION WITHIN

THE UNITED STATES OF SUBVERSIVE AND UN-AMERICAN PROPAGANDA THAT IS

INSTIGATED FROM FOREIGN COUNTRIES OR OF A DOMESTIC ORIGIN AND ATTACKS

THE PRINCIPLE OF THE FORM OF GOVERNMENT AS GUARANTEED BY OUR

CONSTITUTION, AND (3) ALL OTHER QUESTIONS IN RELATION THERETO THAT

WOULD AID CONGRESS IN ANY NECESSARY REMEDIAL LEGISLATION

APPENDIX VI

REPORT ON JAPANESE ACTIVITIES

REPORT ON JAPANESE ACTIVITIES

Printed for the use

of the Special Committee on Un-American Activities

UNITED STATES

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON : 1942

UNITED STATES

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON : 1942

SPECIAL COMMITTEE

ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES

Washington, D. C.

MARTIN DIES, Texas, Chairman

JOE STARNES, Alabama

HARRY P. BEAM, Illinois

JERRY VOORHIS, California

NOAH M. MASON, Illinois

JOSEPH E. CASEY, Massachusetts

J. PARNELL THOMAS, New Jersey

ROBERT E. STRIPLING, Chief Investigator

J. B. MATTHEWS, Director of Research

Washington, D. C.

MARTIN DIES, Texas, Chairman

JOE STARNES, Alabama

HARRY P. BEAM, Illinois

JERRY VOORHIS, California

NOAH M. MASON, Illinois

JOSEPH E. CASEY, Massachusetts

J. PARNELL THOMAS, New Jersey

ROBERT E. STRIPLING, Chief Investigator

J. B. MATTHEWS, Director of Research

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

SECTION I: JAPAN'S ADVANCE WARNINGS TO THE UNITED STATES

SECTION II: JAPANESE NAVAL MAP OF THE PACIFIC AREA

SECTION III: A JAPANESE HANDBOOK ON THE UNITED STATES NAVY

SECTION IV: TECHNIQUES FOR JAPANESE ESPIONAGE

SECTION V: JAPANESE FISHING BOATS

SECTION VI: JAPANESE TREATY MERCHANTS

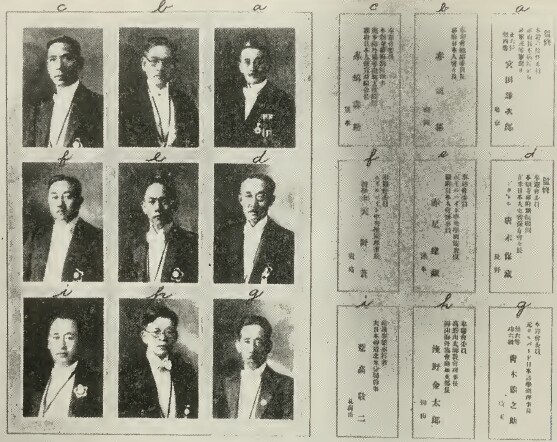

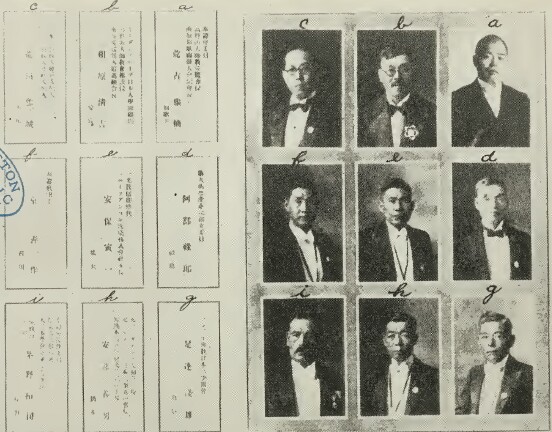

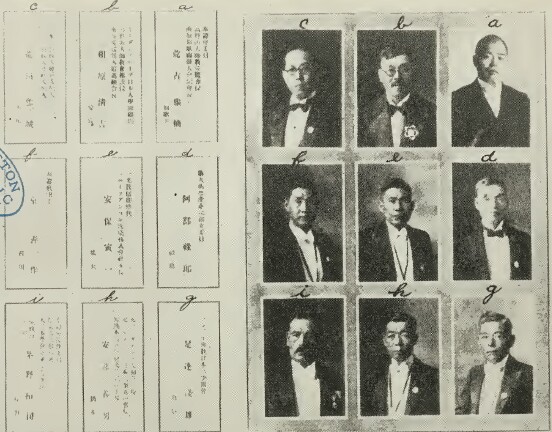

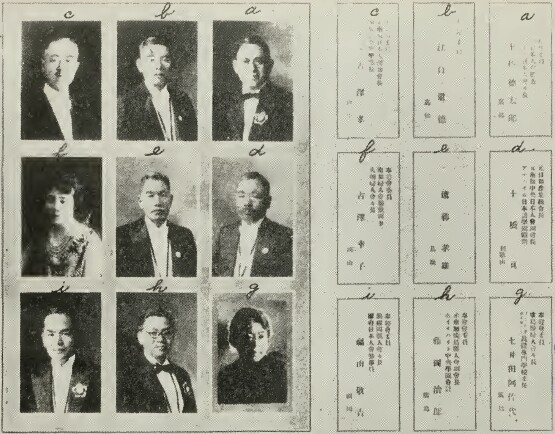

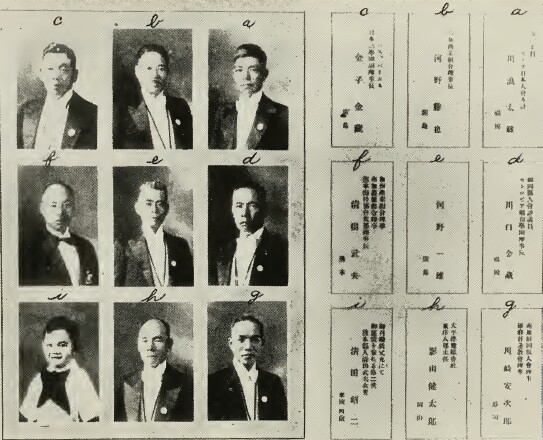

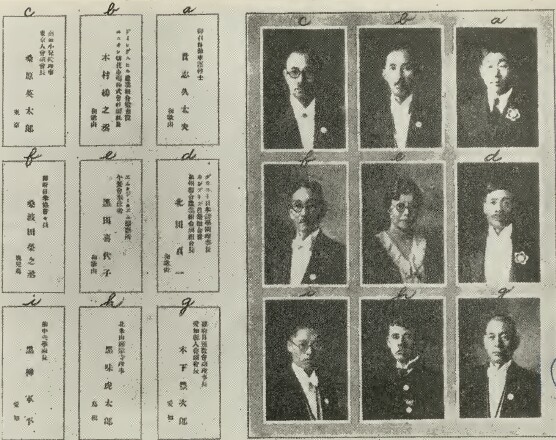

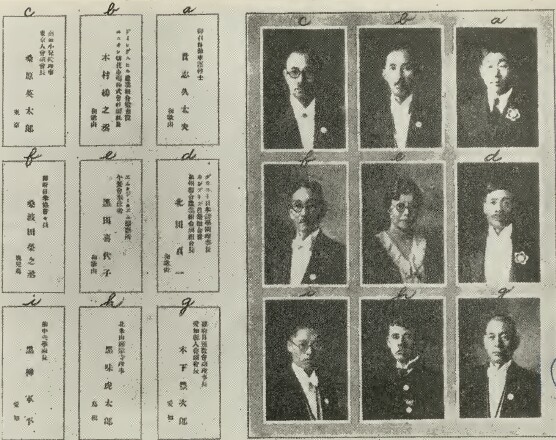

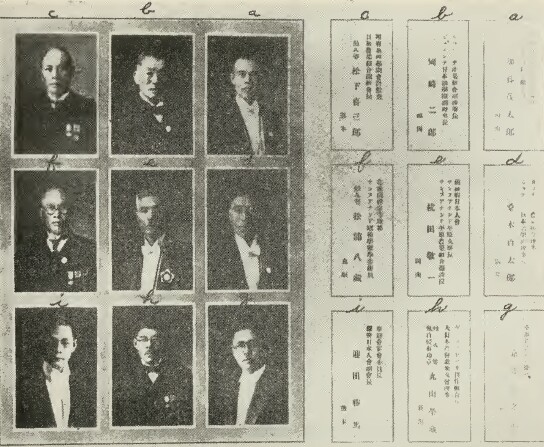

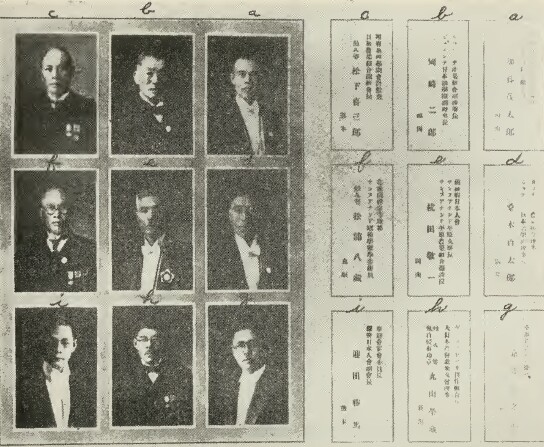

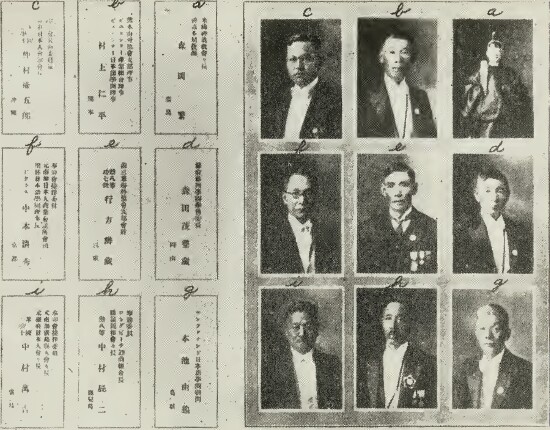

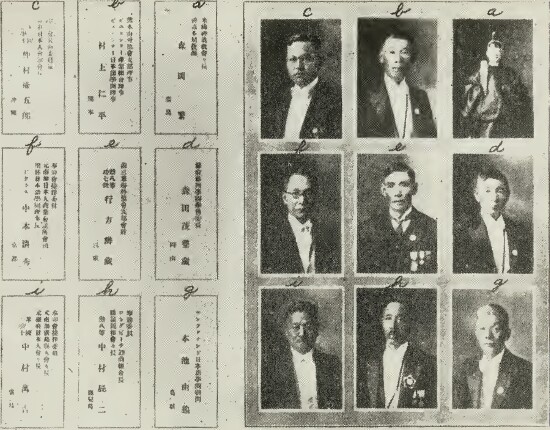

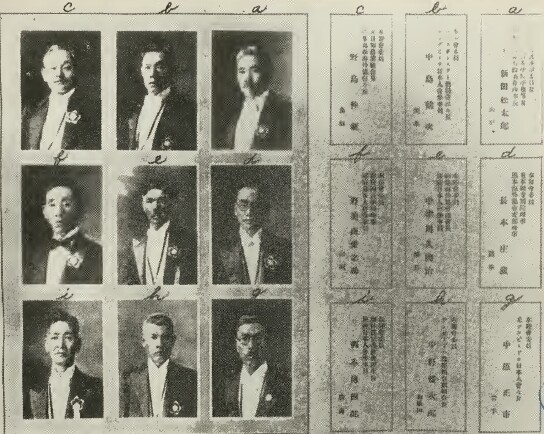

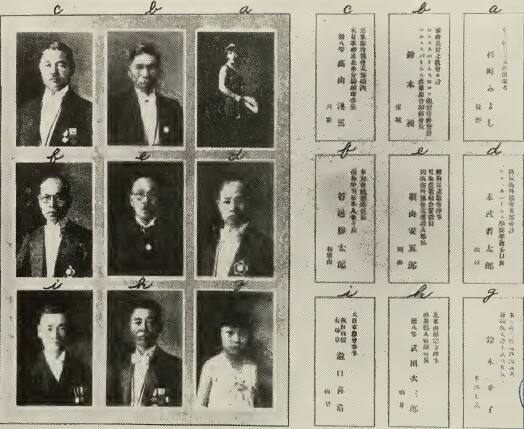

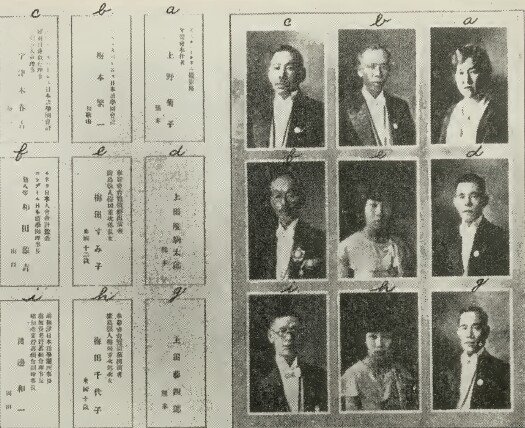

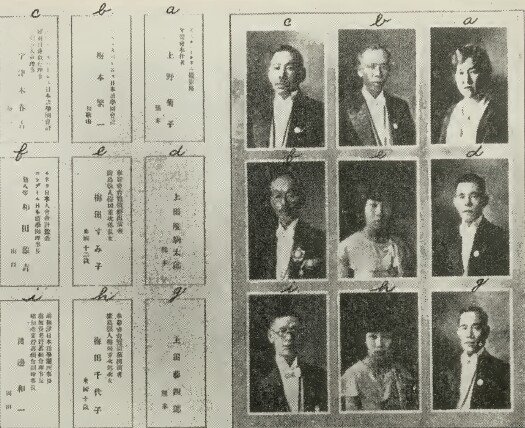

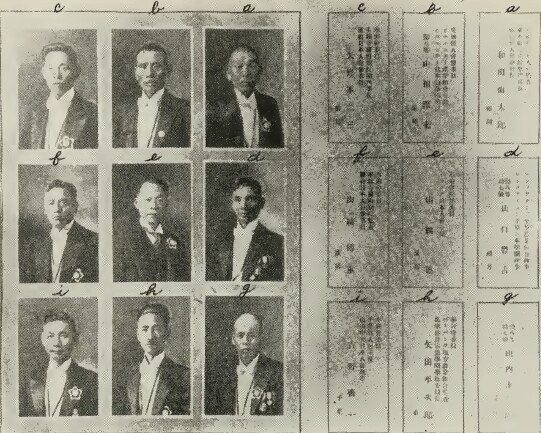

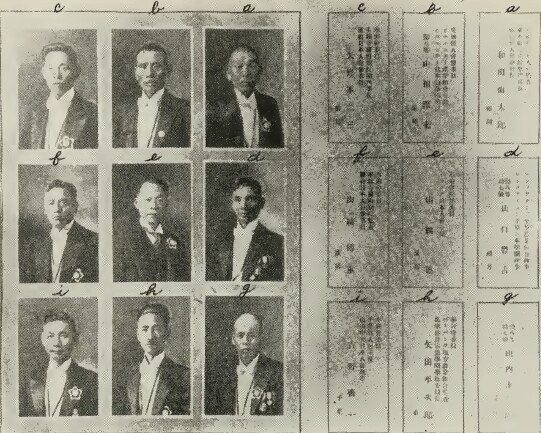

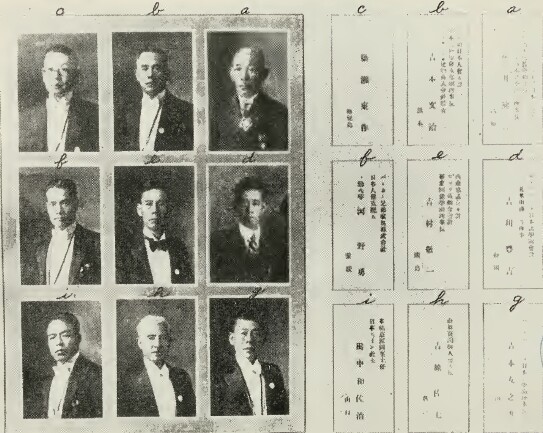

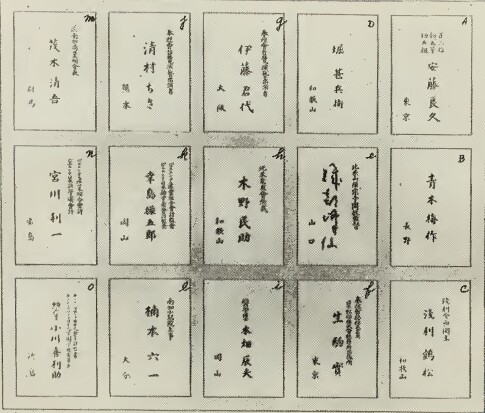

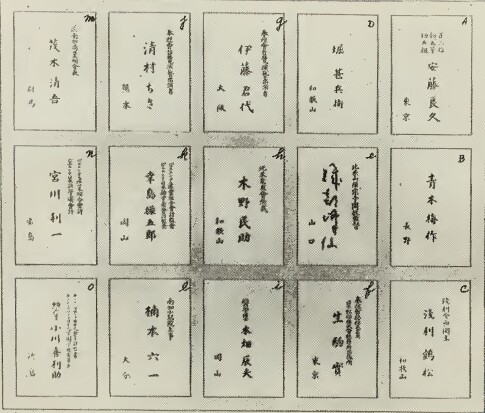

SECTION VII: EMPEROR-DECORATED JAPANESE IN THE UNITED STATES

SECTION VIII: CENSUS OF JAPANESE IN THE UNITED STATES

SECTION IX: JAPANESE LANGUAGE SCHOOLS

SECTION X: CENTRAL JAPANESE ASSOCIATIONS

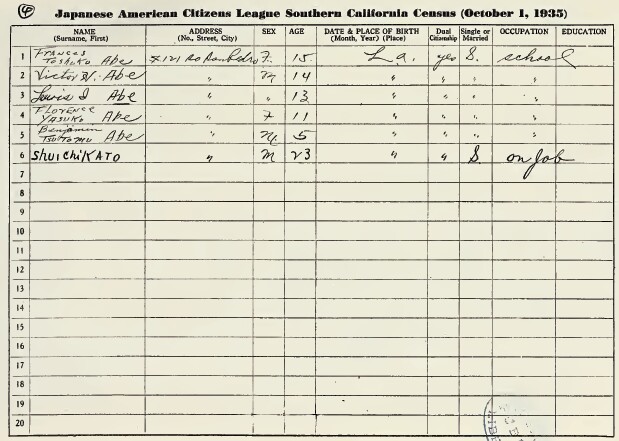

SECTION XI: JAPANESE AMERICAN CITIZENS' LEAGUE

SECTION XII: JAPANESE MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS IN THE UNITED STATES

SECTION XIII: KEN AND PREFECTURAL ORGANIZATIONS

SECTION XIV: PRO-AXIS PROPAGANDA IN JAPANESE PUBLICATIONS

SECTION XV: JAPANESE BUDDHISM

SECTION XVI: THE TANAKA MEMORIAL

SECTION XVII: MEMORANDUM CONCERNING EXCLUSION OF JAPANESE FROM THE UNITED STATES

SECTION XVIII: MEMORANDUM ON STATEHOOD FOR HAWAII

SECTION XIX: BACKGROUND OF THE JAPANESE PROBLEM IN CALIFORNIA AS OF SEPTEMBER 1941

SECTION I: JAPAN'S ADVANCE WARNINGS TO THE UNITED STATES

SECTION II: JAPANESE NAVAL MAP OF THE PACIFIC AREA

SECTION III: A JAPANESE HANDBOOK ON THE UNITED STATES NAVY

SECTION IV: TECHNIQUES FOR JAPANESE ESPIONAGE

SECTION V: JAPANESE FISHING BOATS

SECTION VI: JAPANESE TREATY MERCHANTS

SECTION VII: EMPEROR-DECORATED JAPANESE IN THE UNITED STATES

SECTION VIII: CENSUS OF JAPANESE IN THE UNITED STATES

SECTION IX: JAPANESE LANGUAGE SCHOOLS

SECTION X: CENTRAL JAPANESE ASSOCIATIONS

SECTION XI: JAPANESE AMERICAN CITIZENS' LEAGUE

SECTION XII: JAPANESE MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS IN THE UNITED STATES

SECTION XIII: KEN AND PREFECTURAL ORGANIZATIONS

SECTION XIV: PRO-AXIS PROPAGANDA IN JAPANESE PUBLICATIONS

SECTION XV: JAPANESE BUDDHISM

SECTION XVI: THE TANAKA MEMORIAL

SECTION XVII: MEMORANDUM CONCERNING EXCLUSION OF JAPANESE FROM THE UNITED STATES

SECTION XVIII: MEMORANDUM ON STATEHOOD FOR HAWAII

SECTION XIX: BACKGROUND OF THE JAPANESE PROBLEM IN CALIFORNIA AS OF SEPTEMBER 1941

REPORT ON JAPANESE ACTIVITIES

More than a year ago, the Special Committee on Un-American Activities began an intensive investigation of Japanese propaganda and espionage in the United States. In order to gain access to important material which was locked up in the Japanese language, the committee retained investigators and informers who were acquainted with the Nipponese tongue.

Material already in the possession of the committee revealed certain facts which constituted the basis of the committee's decision to make a more thorough investigation of Japanese activities than it had hitherto undertaken. These facts may be briefly summarized, as follows:

(1) When the committee seized the files of the Transocean News Service, it obtained correspondence between Nazi and Japanese agents which revealed the Axis strategy of Japan's engaging the United States in the Pacific area in order to divert from the Atlantic war zone the ever-increasing supplies which the United States was furnishing the British under the terms of lend-lease. This correspondence was published in the committee's report (issued in November 1940) on the activities of the Transocean News Service.

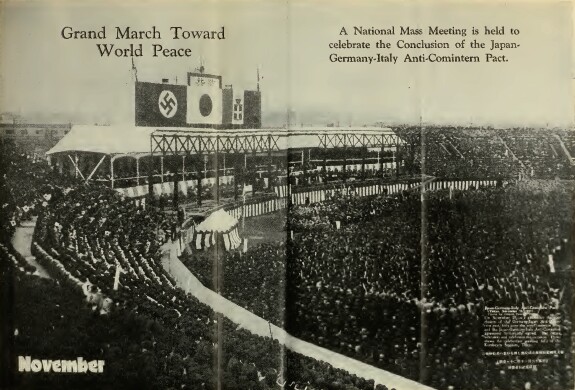

(2) Japan had become a full-fledged Axis partner in 1940. This was tantamount to an announcement that Japan would eventually, at whatever moment the Axis considered most strategic, enter the war as a full military partner of the Nazis.

(3) Japan had long ago announced her own imperialistic ambitions, with the frank recognition that these ambitions were absolutely incompatible with the interests of the United States in the Pacific area. In the well-publicized Tanaka Memorial, submitted to the Japanese Emperor in 1927, Japan had declared bluntly: ''We must first crush the United States."

(4) The foregoing facts added up to make the Japanese residents of California, Hawaii, the Philippine Islands, and the Panama Canal region a menacing fifth column in the Territories of the United States.

The committee proceeded with its wholly inadequate staff and limited funds to employ special investigators to probe as deeply as possible into the activities of the Japanese.

By August 1941 the committee had assembled a large amount of evidence which more than confirmed the suspicions which it had entertained on the basis of surface appearances. This evidence made it unmistakably clear that certain conclusions were unavoidable. These conclusions were as follows:

(1) The Japanese Government contemplated an early attack upon the United States, and specifically included Pearl Harbor as a major objective. The proof of this was generally available, as will appear in section I.

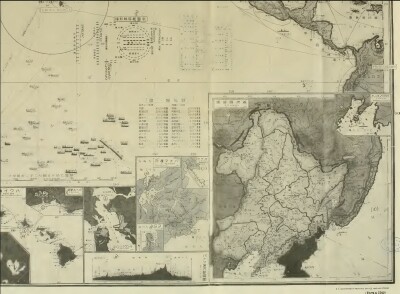

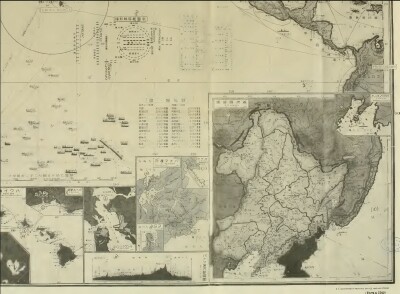

(2) The Japanese had a map showing in great detail fleet positions and battle formations of the United States Navy around Pearl Harbor. This map also included vital military information on the Panama Canal and the Philippine Islands. The map is reproduced between pages 1741 and 1742.

(3) The Japanese were in possession of the most detailed information concerning all the naval craft of the United States. The committee obtained a copy of the document establishing this fact.

(4) The Japanese Government was relying upon its expatriated citizens in California, Hawaii, the Philippines, and the Panama Canal region, as well as upon American-born Japanese, to serve as a fifth column.

(5) A former attaché of the Japanese Consulate in Honolulu was prepared to testify that an elaborately organized fifth column of Japanese was being drilled for collaboration with the armed forces of Japan when the latter should attack Pearl Harbor.

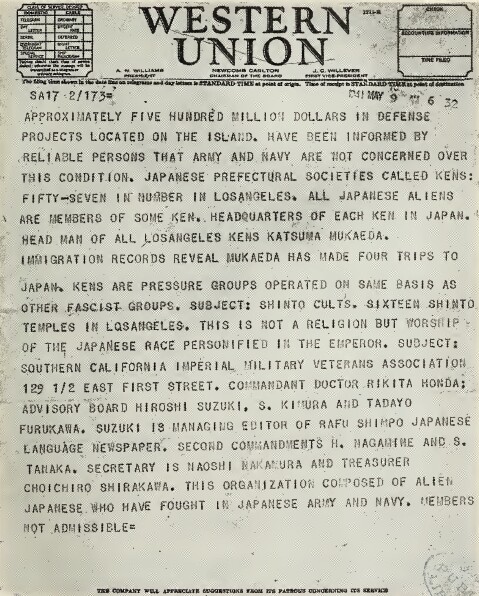

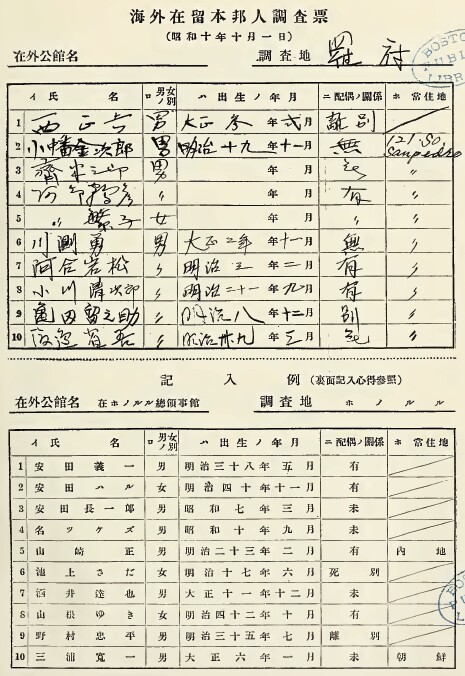

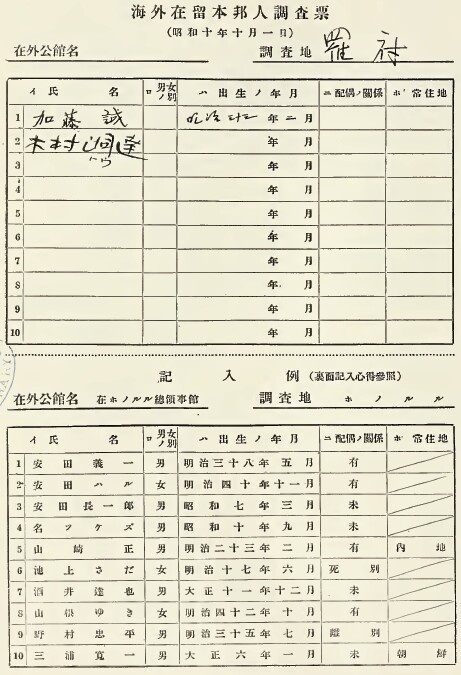

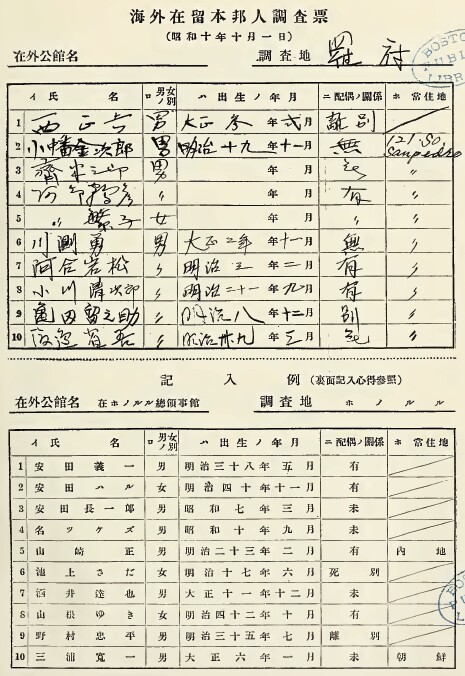

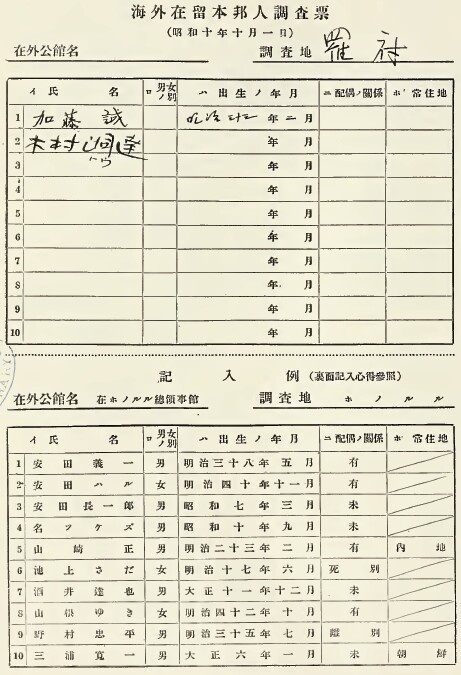

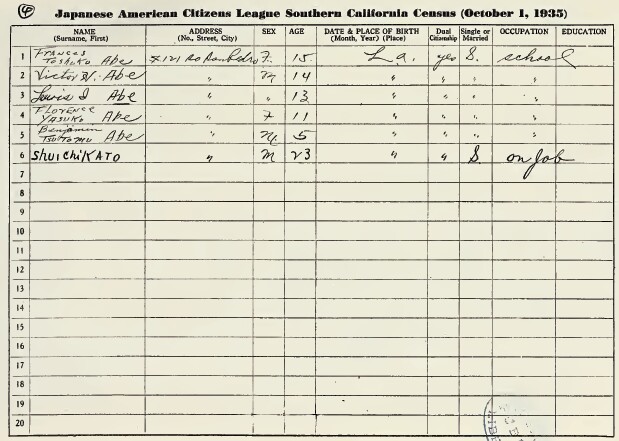

(6) The Japanese Government was using front organizations in this country for the compiling of an elaborate census of Japanese residing in the United States.

(7) Japanese espionage in the Territories of the United States was widespread and most alarming in character.

(8) The Japanese Government was hypocritically going through the motions of diplomatic negotiations with the United States Government, without entertaining the slightest thought that the problems of the Pacific were susceptible of amicable adjustment.

(9) The Japanese Government was irrevocably committed as a military ally of the Third Reich, and was awaiting only the orders of Hitler before striking. The two Governments were in closest collaboration.

(10) The Nazis were schooling the Japanese in all the elaborately developed techniques of espionage and fifth-column activity, employed so successfully by the Nazis themselves in France, Norway, Holland, and Belgium, in order that the Japanese might use these techniques in the Territories of the United States.

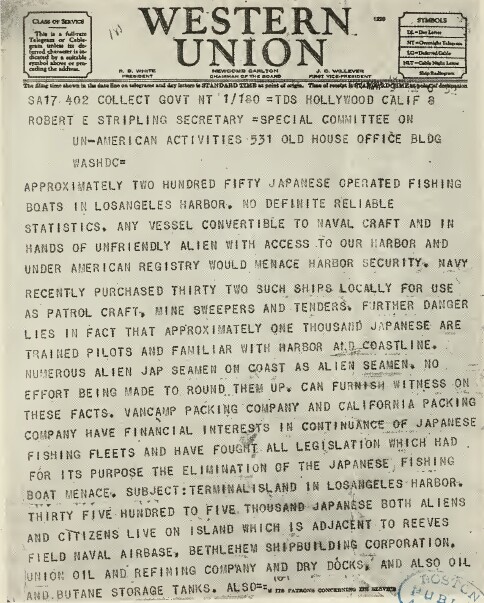

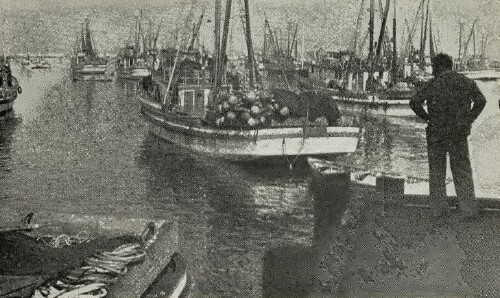

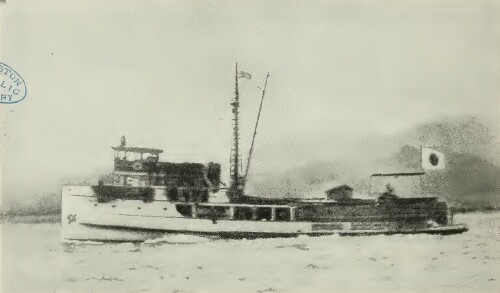

(11) Japanese fishing vessels on our west coast, as well as in Hawaii and the Philippine Islands, were an important arm of the espionage and fifth-column department of the Japanese Government.

(12) A police officer on Terminal Island was prepared to testify that numerous conferences had been held between officers of the Imperial Japanese Navy and Japanese residents on the island.

(13) Japanese-language schools in California and in Hawaii were inculcating traitorous attitudes toward the United States in the minds of American-born Japanese (citizens of the United States), and these language schools were becoming an ever more important arm of Japanese espionage for Japanese citizens residing in the Territories of the United States.

(14) Japanese civic organizations in the United States, such as the Central Japanese Association, were loudly pretending their loyalty toward the United States Government while surreptitiously serving the deified Emperor of Japan.

(15) Japanese residing in the United States were raising large sums of money which were being sent to Japan for the Empire's war chest to be used for purchasing bombers. Civic organizations such as the Central Japanese Association were used by the Japanese Government for collecting these funds.

(16) In California there were Japanese veterans' organizations composed of men with military training and experience who vowed allegiance only to the Japanese Emperor whether their members were American or Japanese born.

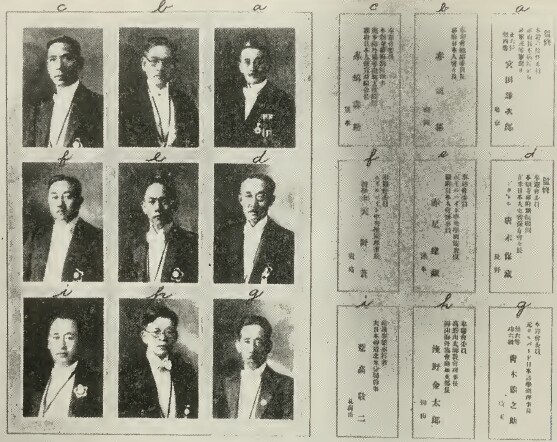

(17) Hundreds of Japanese residing in the United States, including those who are citizens of this country, had been decorated by the Japanese Emperor.

(18) Japanese treaty merchants, abusing the hospitality of the United States and using their merchant status as a subterfuge, were engaged in espionage activities for the Japanese Government.

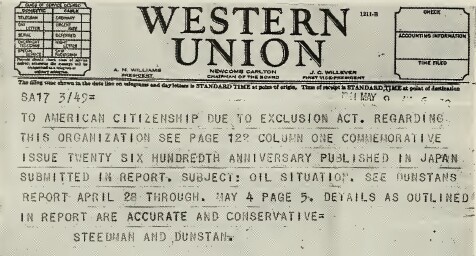

(19) The question of the dual citizenship of American-born Japanese had become increasingly grave as the Japanese Government was planning for the moment to strike against the Territories of the United States.

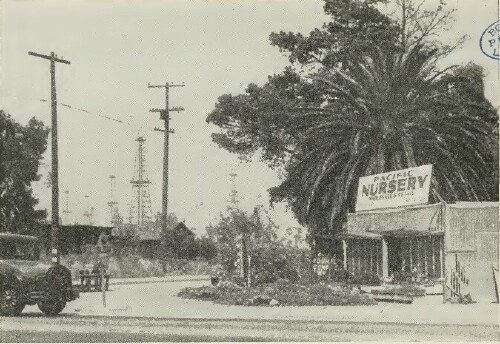

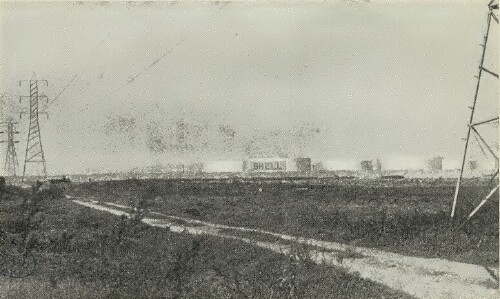

(20) Japanese in California were occupying tracts of land which were militarily but not agriculturally useful.

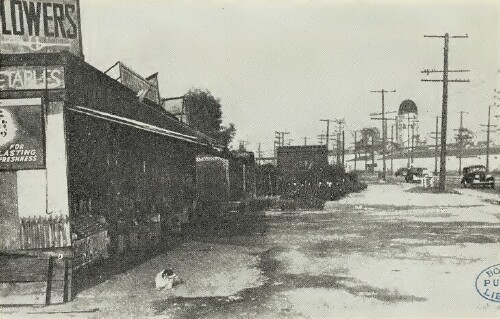

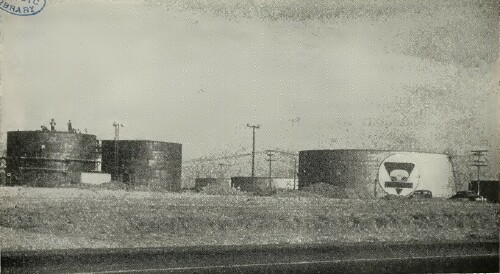

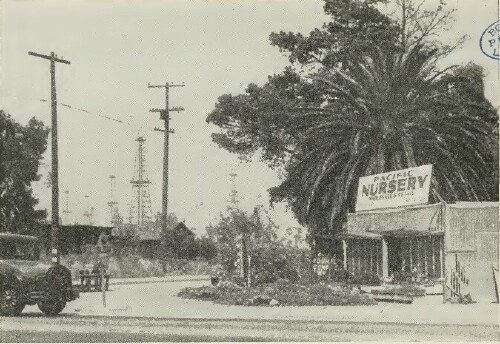

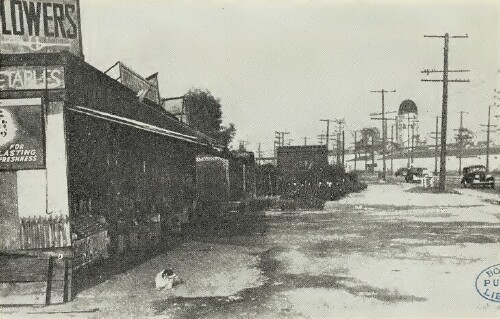

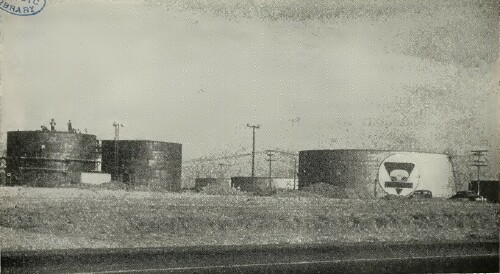

(21) Japanese had taken up residence adjacent to highly important defense plants, and were especially concentrated on Terminal Island in the harbor of Los Angeles.

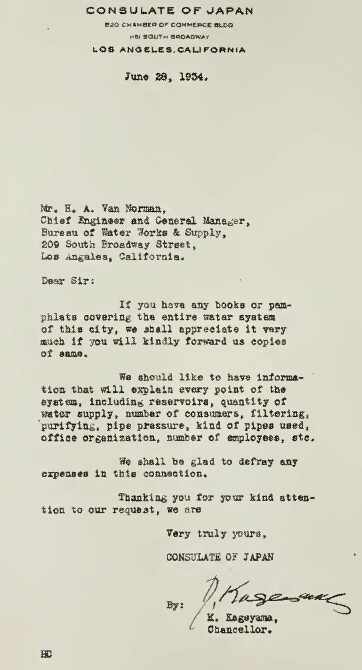

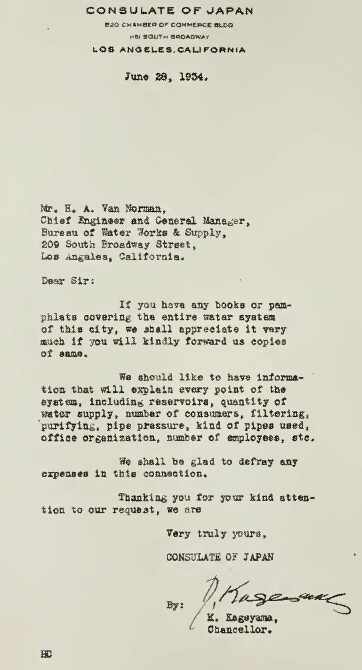

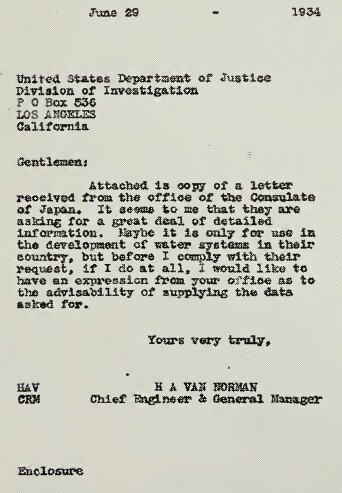

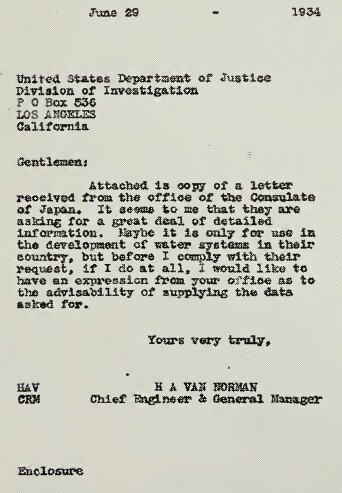

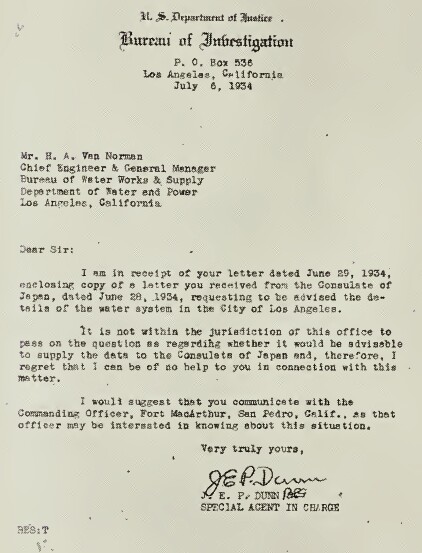

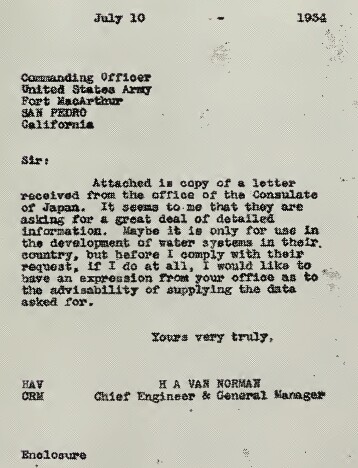

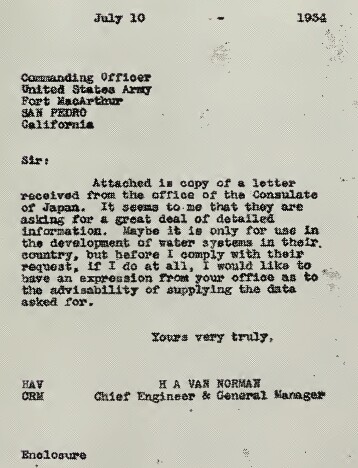

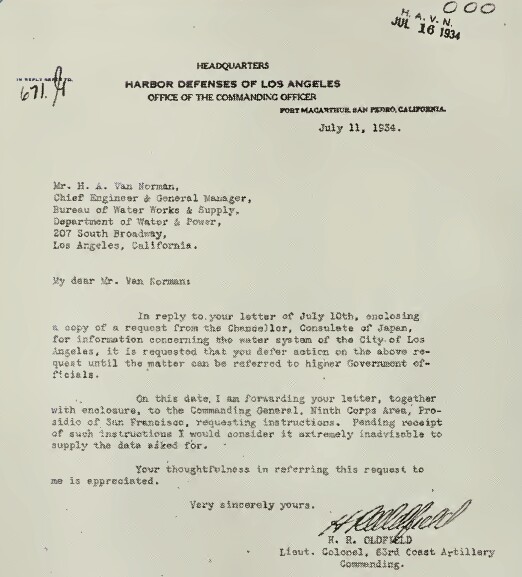

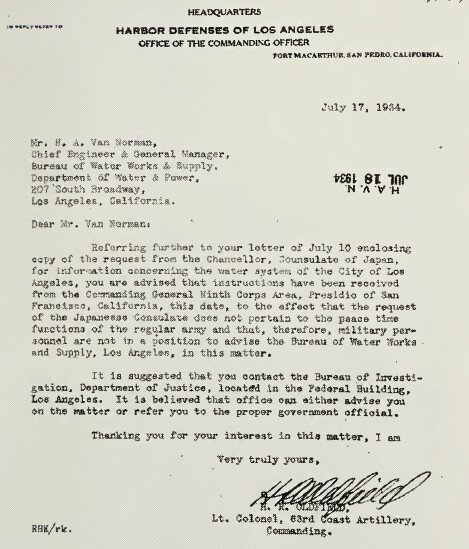

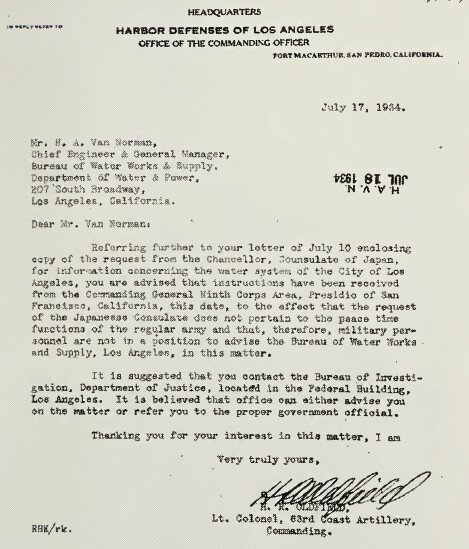

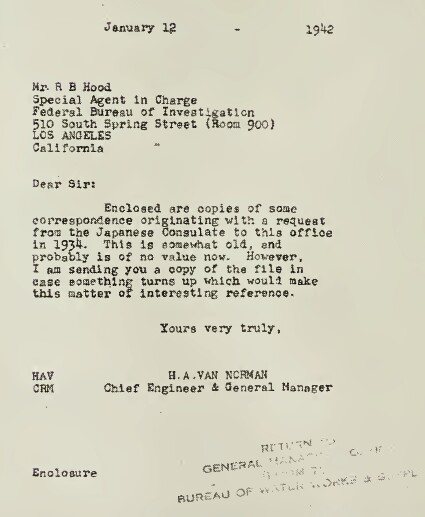

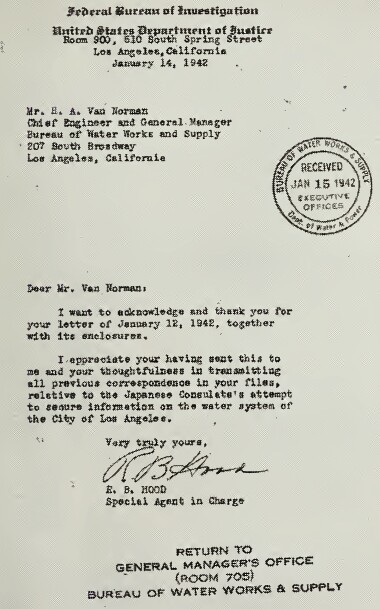

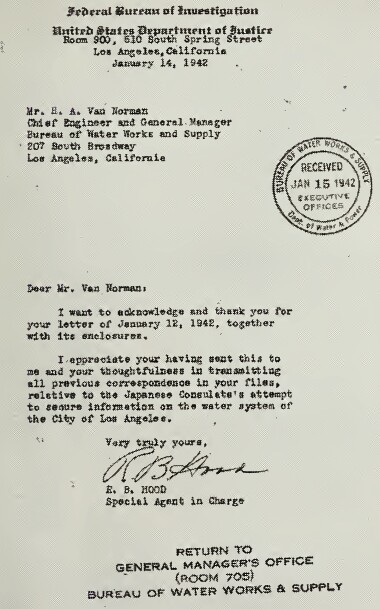

(22) Having failed through diplomatic channels to obtain important information concerning the water-supply system and other public utility services of Los Angeles, Japanese had obtained employment in these places where they were in a position to do incalculable fifth-column damage.

(23) The Japanese Government was engaged in flooding the United States with printed Axis propaganda for distribution among Japanese in this country.

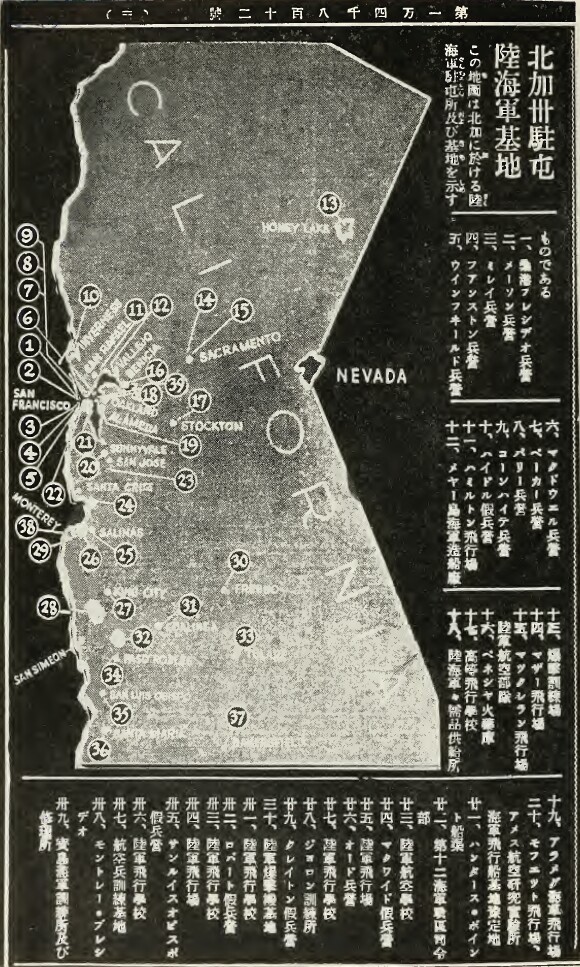

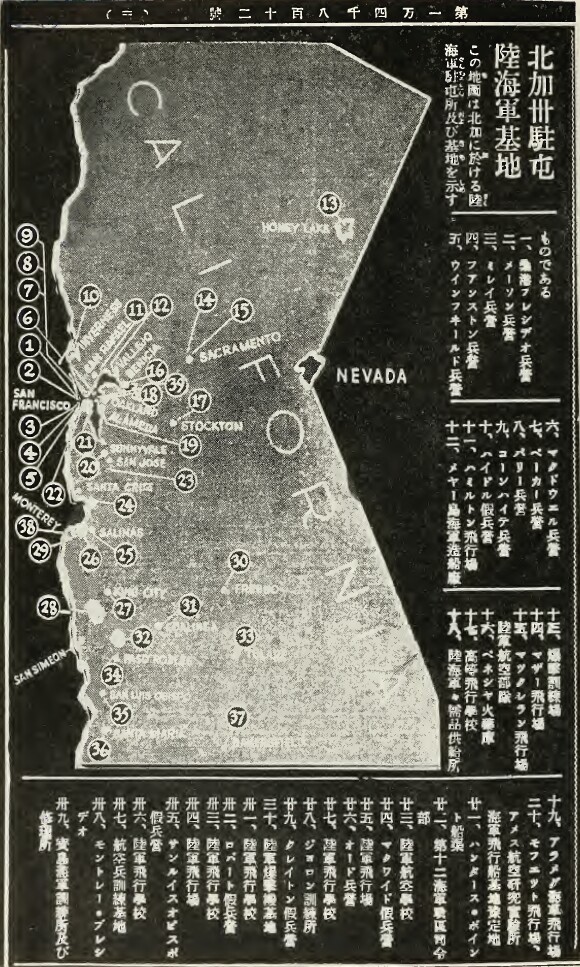

(24) Several maps containing highly important military information, such as the location of the airports of California, were obtained from Japanese sources.

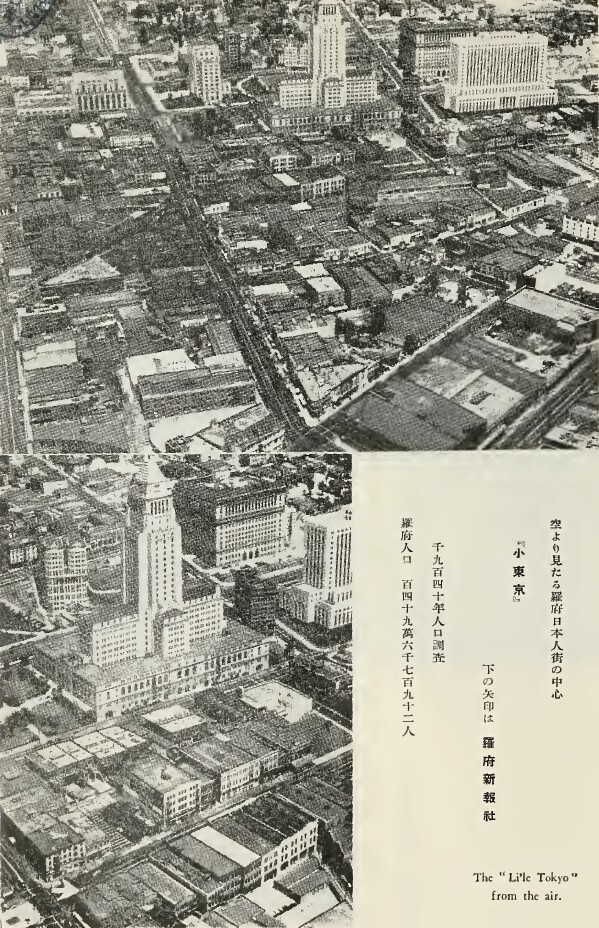

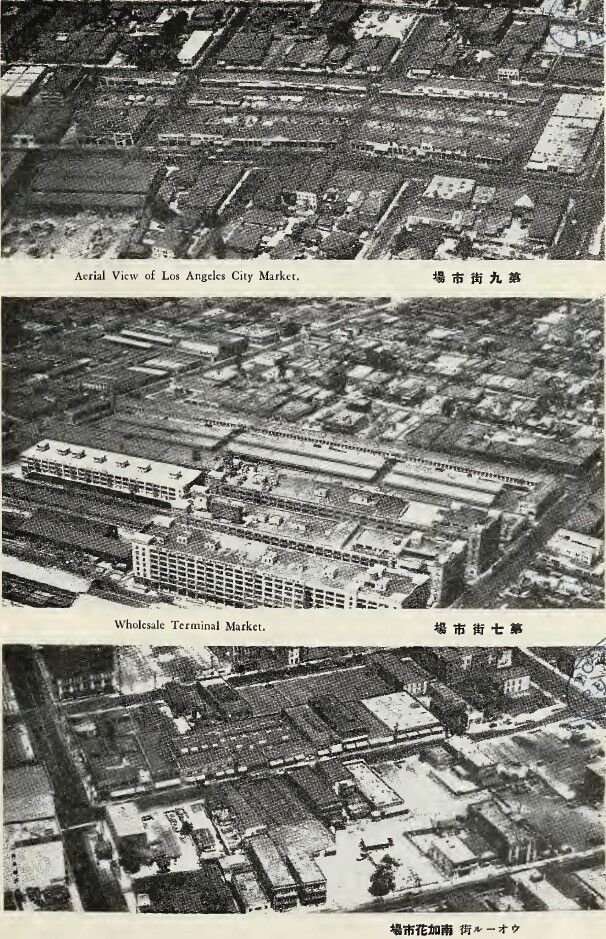

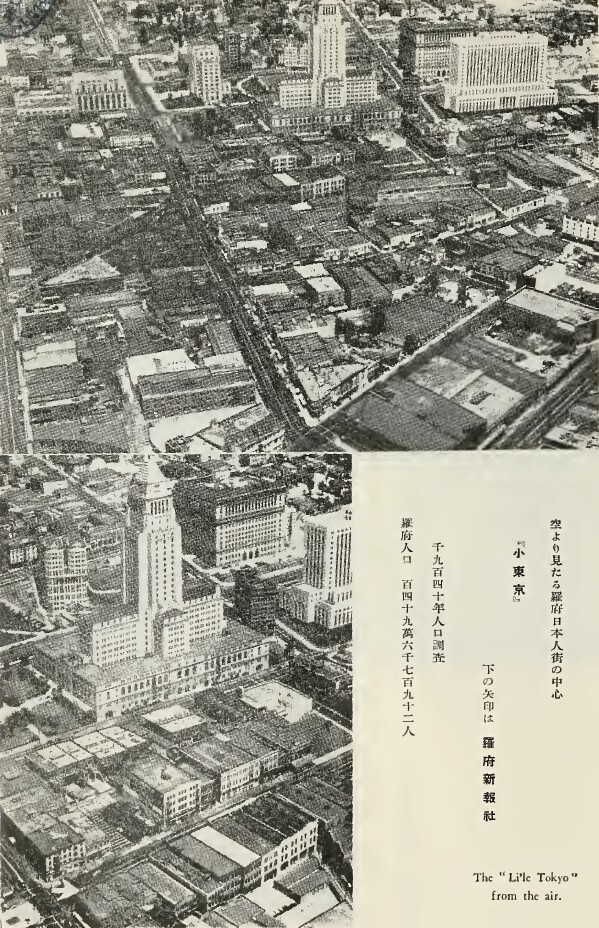

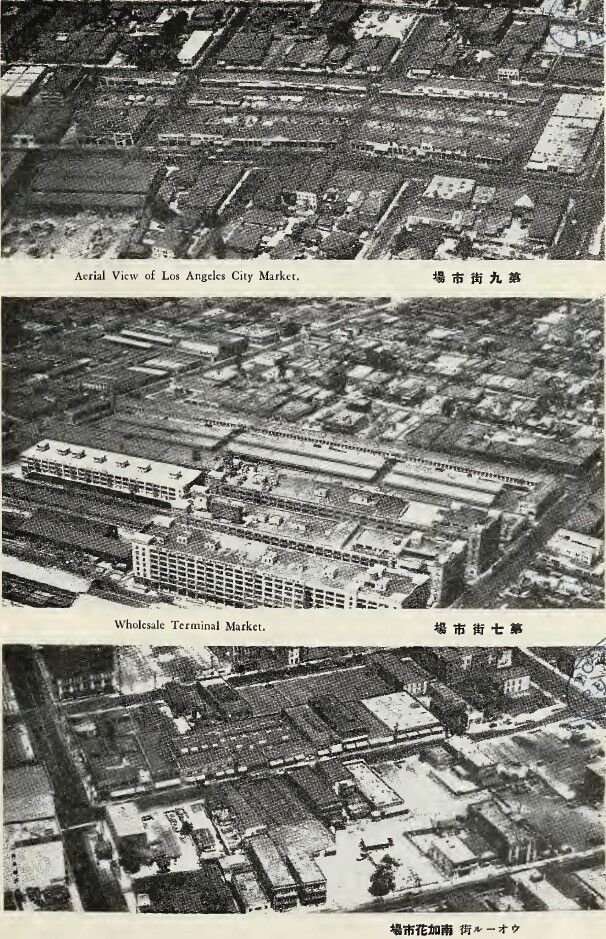

(25) Japanese were in possession of aerial photographs of every important city on the west coast, as well as of the vital Gatun locks in the Panama Canal.

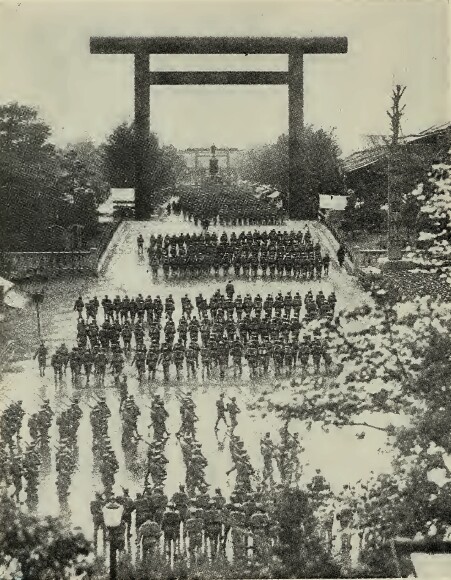

(26) Japanese religious institutions, Shintoism, Buddhism, and Bushido were being used in the Territories of the United States as fifth-column instruments for the coming attack on the United States.

(27) Finally, it was apparent from all the evidence in hand that the hour was rapidly approaching when the next step in the timetable of the Tanaka Memorial was about to be taken, namely the effort of the Japanese Government to "crush the United States."

Having assembled a vast quantity of documentary evidence to establish the foregoing facts, and having found witnesses who would testify in support of these conclusions, the committee was of the belief that the time had arrived to arouse the whole American people into a sense of the impending crisis. The committee accordingly made arrangements for 52 witnesses to proceed to Washington for public hearings early in September 1941.

Among these 52 witnesses called by the committee, were the following: A number of fishermen who had fished up and down the Pacific coast from Alaska to Panama ; Terminal Island police officers; Japanese leaders and a number of Nisei (American-born Japanese), a group which would have been compelled to testify in the utmost secrecy, but whose testimony was to have been made public; a Federal judge who had made a complete study of Japanese evasions of American laws; and a former attaché of the Japanese consulate in Honolulu.

Before proceeding to actual hearings, the chairman of the Special Committee on Un-American Activities addressed a communication to the Attorney General for the purpose of ascertaining whether or not such hearings would be satisfactory from the standpoint of the administration's plans as they related to the Japanese.

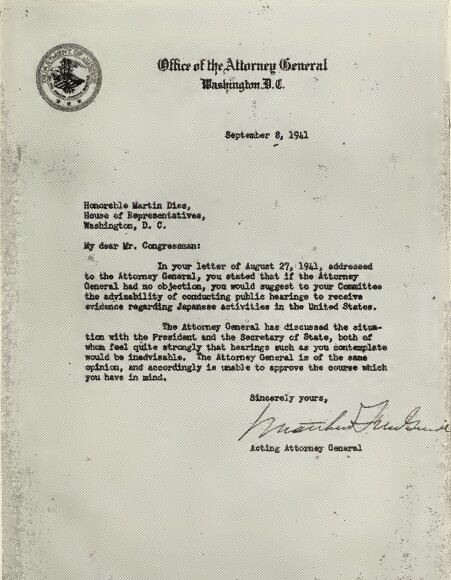

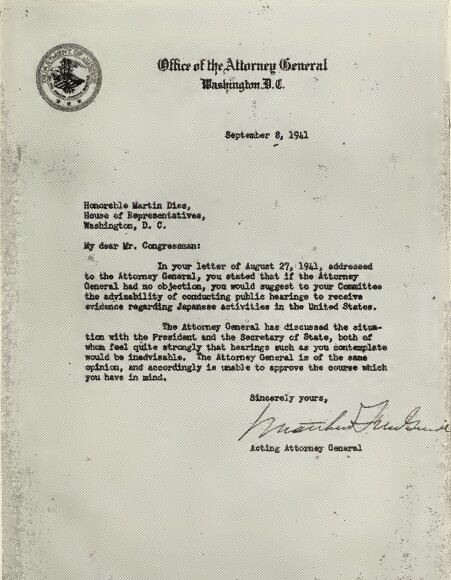

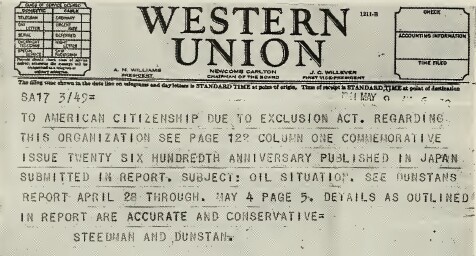

In response to the chairman's inquiry, the Acting Attorney General sent the following reply, a photographic reproduction of which appears on the opposite page:

Office

of the Attorney General,

Washington, D. C, September 8, 1941.

Washington, D. C, September 8, 1941.

Hon. Martin Dies,

House of Representatives, Washington, D. C.

My dear Mr. Congressman: In your letter of August 27, 1941, addressed to the Attorney General, you stated that if the Attorney General had no objection, you would suggest to your committee the advisability of conducting public hearings to receive evidence regarding Japanese activities in the United States.

The Attorney General has discussed the situation with the President and the Secretary of State, both of whom feel quite strongly that hearings such as you contemplate would be inadvisable. The Attorney General is of the same opinion, and accordingly, is unable to approve the course which you have in mind.

Sincerely yours,

Matthew F. McGuire,

Acting Attorney General.

Acting Attorney General.

EXHIBIT NO. 1

In deference to the opinions of these high Government personages, who were primarily responsible for the conduct of our foreign relations, the committee abandoned its plans for the public hearings.

However, the committee's evidence was made available to the appropriate agencies of our Government. The Military Intelligence has gone over all of it.

With the firm conviction that much of its evidence may yet be used to important educational advantage since the people of this country have yet much to learn on the operations of the fifth column in the United States, and with undisguised fear that our west coast and the Panama Canal are still in the gravest peril from Japanese, espionage and Japanese attack, the committee now presents a part of the evidence which it had compiled prior to December 7, 1941.

II

Throughout the summer of 1941, when the committee's findings were taking shape, the chairman of the Special Committee on Un-American Activities made available to the press of the country certain portions of the committee's evidence in the hope that this evidence would serve as a warning to the country at large even before the committee would be able to hold extensive hearings on Japanese espionage.

On July 5, 1941, the following story appeared in the Los Angeles Evening Herald and Express:

DIES GROUP TO PROBE

ESPIONAGE ON COAST

Washington, July 5. -- The Dies committee will launch a series of public hearings in the near future which will include a searching inquiry into activity of alleged Japanese espionage organizations on the Pacific coast, it was disclosed today.

Committee plans also call for issuance of a Fascist book, describing activity of Fascist organizations in the United States, and hearings upon Communist and Nazi penetration of labor unions.

An important public hearing, the nature of which is being kept secret, is planned in New York. Another hearing is scheduled to be held in Philadelphia. The proposed public inquiry into Japanese activities on the Pacific coast will follow a long secret investigation by a corps of committee investigators. They have submitted reports, it was learned, asserting that many Japanese societies are under control of Japanese propaganda agencies and are actively engaged in promoting interests of the foreign power.

The inquiry, it is understood, will deal with activities of Japanese fishing fleets on the Pacific coast, long a bone of contention, with California congressional representatives openly asserting that agents on the boat are engaged in spying activities.

On July 6, 1941, the following story appeared in the Los Angeles Examiner:

JAPANESE SPYING

FACES DIES QUIZ -- COAST FISHING FLEET CALLED COVER FOR

NAVY PLOT

Washington, July 5. -- (I. N. S.). -- Amid signs of gathering war clouds in the far Pacific, the Dies committee tonight announced a searching inquiry would be opened shortly into alleged espionage activities of Japanese agents on the west coast of the United States.

While secretive about the two public hearings scheduled for New York and Philadelphia, the Dies committee readily admitted today that emphasis will be placed at the Washington hearing on Japanese activities on the Pacific coast.

LINKED TO NAVY

According to investigators who have been rounding up the evidence for many weeks, Japanese fishing fleets, long a bone of contention on the west coast, are cover-ups for espionage work and manned by Reserve officers of the Imperial Navy.

Several California Congressmen will take the stand at the hearing, said committee members, and will testify that the fishing fleets are engaged in spying activities.

The committee investigators said they will also reveal at the hearing that the thousands of Japanese on the west coast are under the direct domination of Japan and cooperating fully with their mother country in fifth column spy and traitor activities.

The Nipponese, said the Dies agents, do not stir up internal trouble like the Nazis and Communists, but operate entirely as spies, and send important military and State information to Japan.

1,000 BOATS IN FLEET

The innocuous Japanese fishing fleet of some 1,000 boats, the Committee on Un-American Activities stated, has been locating certain strategic naval operations and could cause serious trouble if Japan and the United States severed relations.

The committee asserts this fleet is ready to dynamite and bomb when and if the order comes from the Imperial Navy.

Asserting that Communist activity in this country has speeded up its tempo and redoubled its efforts since outbreak of the Soviet-Nazi war, the committee will also continue hearings on allegedly Red organizations. Future hearings, the committee said, will inquire further into the American Peace Mobilization, which picketed the White House up until the outbreak of the Russian war and then dropped quickly from sight.

BORING FROM WITHIN

Sensational new testimony at the Philadelphia hearing, said the investigators, will reveal deeper penetration of Nazis and Communists into the ranks of American labor unions and defense industries.

In the giant Washington round-up of un-American activities the Dies hearing plans also call for the issuance of a "Fascist book" which will list all Fascist organizations, members, and their positions.

According to the specially picked corps of Dies agents, who have just completed a lengthy tour of secret investigations, the United States is literally pockmarked with foreign agents promoting the Axis and Communist interests. Japanese companies and societies, they claim, are working actively for foreign powers under the commands of the Japanese Government, and Nazis, Communists, and Fascists have increased their membership and their espionage to a highly dangerous degree.

On July 22, 1941, the following story appeared in the Los Angeles Evening Herald and Express:

JAPAN AIDES FACE

PROBE BY DIES

[By International News Service]

[By International News Service]

Washington, July 22. -- Dies committee investigators today declared that they have gathered "sensational evidence" regarding asserted propaganda and other un-American activities of Japanese consular agencies in this country.

This evidence, they said, will be made public soon when general hearings on alleged Japanese espionage are started.

Although it was previously announced that evidence is in hand regarding Japanese activities on the west coast, this was the first intimation that consular agencies were involved.

It was recalled that the committee previously uncovered similar evidence about German and Italian consular agencies in this country. This was withheld from the public for many months pending a State Department check. It ultimately resulted in the German and Italian consuls being ordered out of the country.

Although he declined to disclose the nature of the evidence, Representative Dies, Democrat of Texas, chairman of the committee said that "German, Italian and Japanese consulates have been a focal point of subversive activities in America."

"These people, under the cloak of diplomatic immunity, have been carrying on work inimical to the welfare of the United States," Dies added. "It is time we had a showdown on all phases of the question."

On July 23, 1941, the following story appeared in the Los Angeles Examiner:

DIES CHARGES TOKYO

AIDES WITH SABOTAGE -- PROBER SAYS EVIDENCE WILL BE

PRESENTED SOON; SENATE VOTES CIVILIAN NAVY BASE GUARDS

(By Lee Rashall, staff correspondent, International News Service)

(By Lee Rashall, staff correspondent, International News Service)

Washington, July 22. -- Chairman Dies (Democrat), Texas, of the Special Committee on Un-American Activities, declared tonight he will soon call for expulsion from the United States of all Japanese consuls.

The Dies bombshell coincided with revelation in the Senate by Senator Walsh (Democrat), Massachusetts, chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee, that there are evidences of "widespread sabotage" throughout the Nation's naval shore establishments.

GUARDS VOTED

Over sharp objections that it would mean an "OGPU" for America, the Senate heeded warnings by Walsh, drawn from his confidential files, and passed, 41 to 14, a bill providing $1,000,000 to establish a large civilian police guard for all naval shore establishments.

Dies plans early presentation of evidence to prove that the Japanese consular agencies are guilty of anti-American espionage. He said the data would "leave no other course open to this Government" than to give the consuls their walking papers.

WILL PUBLISH DATA

The chairman said his committee will make public, through open hearings, 'spectacular evidence" regarding consuls of the Far Eastern Axis partner, and, indicating their activities have centered on the Pacific coast, announced 20 witnesses will be subpoenaed from California.

"It is now time for a showdown on Japanese spy activities in this country," Dies said. "This Government has recently expelled the consular agents of Germany and Italy. After the Government learns what we anticipate will be shown, I cannot see how it can elect any other course than to expel the consuls of Japan also."

Expulsion of German and Italian consuls, now en route to their homelands across the Atlantic, was based upon evidence they were engaged in subversive activities inimical to this country.

Although Dies had earlier revealed he had evidence concerning Japanese espionage, he had not previously disclosed that the consuls themselves were involved in it.

Any expulsion of these agents would have to be ordered by the State Department, which presumably will not be consulted by the committee until following the hearings.

Dies would not detail his data, but he said the committee has long been "reasonably sure" that the consulates of Germany, Italy, and Japan were working jointly in propagandistic and spying activities in this country.

On July 31, 1941, the following story appeared in the Los Angeles Daily News:

(NOTE. -- This article is reproduced to show the skepticism voiced by certain publications concerning the Japanese prior to Pearl Harbor.)

DIES RAISES A JAP

BOGEY OFF COAST

Hair-raising tales of how Japanese naval reservists hold torpedo drills, complete with Rising Sun flags just outside the 3-mile limit off San Pedro, were told today by guess who?

Yep, Congressman Martin Dies, (Democrat), who hasn't been much in the public prints since he ran fourth in the recent Texas Senatorial election.

Dies said he has a witness, formerly attached to the Japanese consulate at Hawaii who sat in on secret meetings at Terminal Island, where elaborate sabotage operations were planned.

The chairman of the House Committee Investigating Un-American Activities said today he had temporarily postponed public hearings on this matter to give the Department of Justice a chance to act.

But if the Federal Bureau of Investigation doesn't swoop swift and soon, said Dies, "the American people will get the facts."

These include the often-published reports that fishing boats manned by Japanese are convertible into torpedo boats. Dies said. Such boats, he added, are the ones his man saw at drill practice.

Informed of the Congressman's press release, local Federal Bureau of Investigation officials had no comment.

A spokesman for the naval intelligence office here said the harbor was all secure with everything under control.

He added that the Navy and Coast Guard were maintaining a stringent patrol at least 60 miles out, and that the navy's neutrality patrol was effective considerably beyond the Hawaiian islands.

On August 1, 1941, the following story appeared in the Los Angeles Examiner:

DIES BARES JAPAN

PLOT -- NIPPON FISHING BOATS INVOLVED IN WAR PLOT --

DIES CHARGES SCHEME TO BLOW UP LOS ANGELES HARBOR DEFENSES -- PROBE

LAUNCHED BY G-MEN

Washington, July 31. -- (INS) -- Chairman Dies (Democrat, Texas) of the House Un-American Activities Committee, announced today that his agents have uncovered "a gigantic sabotage plot by the Japanese in California."

Dies said he had evidence that Japanese officers and operators of fishing boats had entered into the plot, which he said had been discussed by them at Terminal Island, Los Angeles Harbor, Calif.

"We have witnesses who actually participated in discussions of proposals to convert Japanese fishing boats into torpedo ships and to get ready to blow up defense installations on the west coast," Dies declared.

AWAITS F. B. I.

PROBE

The Texan said, however, that his committee would hold off in making details public "until the Federal Bureau of Investigation has a chance to clean up the matter."

Dies said that his principal witness is a former attaché of the Japanese consulate in Hawaii. He refused to name this individual, however, who, he said, "says he is acting now through his loyalty to the United States."

Japanese fishing boats operate from Terminal Island and a series of conferences have taken place between Japanese officials and the boat operators, Dies declared.

DEMANDS DEPORTATIONS

"We have many witnesses who have actually seen the things, ready to swear that there have been regular communications between Japanese officials and the boatmen, that these boats are designed so that they are readily convertible into torpedo ships, and that when they got out to sea they often hoist the Japanese flag and hold military drills aboard," he said.

Dies also demanded that steps be taken by this county to deport between 3,000 and 4,000 Japanese commercial agents and some 1,800 students which he says are in this country.

He also asked that Japanese seamen be rounded up in the same way as German and Italian seamen.

On August 1, 1941, the following story appeared in the Los Angeles Times:

DIES DISCLOSES

SABOTAGE PLOT -- TERMINAL ISLE CENTER OF JAPANESE RING

HEADED BY NAVY OFFICERS, F. B. I. TOLD

Washington, July 31 (U. P.) -- Chairman Martin Dies (Democrat), Texas,, of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, said today his investigators have uncovered sensational evidence of an elaborate sabotage plot by Japanese agents on the west coast.

He said the evidence was obtained from a former attaché of the Japanese consulate in Hawaii who has attended secret meetings of the sabotage ring at Terminal Island, off Los Angeles, home of some 5,000 Japanese and site of a vast United States gasoline depot.

The evidence has been turned over to the Justice Department for prosecution of the ring's members. Dies said, but unless the Department acts promptly, he will order public hearings "so the American people can get the facts."

He said committee investigators were told that Japanese naval officers at Terminal Island are cooperating with Japanese fishermen in the area "whose craft are built for easy conversion into torpedo boats." Many of these craft, he added, frequently sail out beyond the 3-mile limit, hoist the Japanese flag "and hold naval drill practice."

Dies said he favored a round-up of all Japanese seamen in this country in order to restrict their activities.

FEDERAL BUREAU OF

INVESTIGATION AGENTS HERE SILENT ON DIES REPORT

Agents at the Federal Bureau of Investigation field office in Los Angeles had "no comment" on the statement from Washington yesterday by Representative Martin Dies that his committee had uncovered evidence of an elaborate Japanese sabotage plot on Terminal Island and along the Pacific coast.

One of the agents asked that the dispatch be read to him over the telephone. "We have no comment to make," he said.

On December 8, 1941, the following story appeared in the Los Angeles Examiner:

DIES URGES SPEEDY

ACTION AGAINST JAPANESE, NAZIS

"We are going to face serious trouble," Dies said, "unless we clean up this whole situation at once. The Japanese and Nazis in this country have been working in very close collaboration. We should proceed immediately not only to round up the Japanese aliens known to be potential saboteurs, but also should clean out the Nazis from our defense industries.

"The Nazis have followed a policy of placing German nationals or Nazi sympathizers in defense industries, particularly technical experts and mechanics. There are a great many members of the German-American Bund and other Nazi organizations scattered through the aircraft and other defense plants."

Dies pointed out that there are 155,000 Japanese residents in the United States of whom 105,000 are in the Pacific coast area. Also, there are about 1,800 Japanese students, whom he said, he was convinced had been sent to the United States to obtain secret information for the Japanese Government. These students, he said, are working through Japanese consular agents. The consular agents, he declared, have been very active in espionage work, as disclosed by evidence gathered by Dies committee investigators.

On July 25, 1927, Gen. Baron Giichi Tanaka, Premier of Japan, submitted to the Emperor a plan for Japanese world conquest. The memorandum has come to be known as the Tanaka Memorial. Its authenticity is beyond dispute.

"We must first crush the United States," wrote Tanaka in his memorandum. According to the timetable which the Japanese Premier laid down in his plan of conquest, Manchuria was to be seized, China was to be invaded, and then in order to consolidate the Japanese victories in these Asiatic countries the United States was to be crushed.

The Tanaka Memorial has been aptly described as the Japanese "Mein Kampf." It must be admitted that, to date, the Nipponese have carried out the plans of the Tanaka Memorial with as much success as Hitler has had in following the outlines of his more famous book.

For 15 years since the writing of the Tanaka Memorial, the Japanese have geared their entire economy to the objectives which it announced. The memorial left no reasonable doubt about the Japanese intentions to strike at the Pacific possessions of the United States. It likewise leaves no doubt about the intentions of the Japanese to attack yet other Territories of the United States. The complete text of the Tanaka Memorial will be found on pages 1859-1977 of this volume.

| {NOTE: The

authenticity of the Tanaka Memorial has been questioned, some claiming

it to

be a forgery. Nevertheless, it's historical importance is not

questionable, nor the corroborative documentation. During the Tokyo War

Crimes Trials, a number of mentions were made of the Tanaka Memorial by

Gen. Ching Teh-Chun (former mayor of Peiping, China); see this excerpt

from the IMTFE Summary of Trial Proceedings, Gen. Ching Teh-Chun re Tanaka Memorial, war preparations, Nanking: "I saw the Chinese translation of the Tanaka Memorial. It does not matter very much whether Tanaka Memorial ever existed or not.

Even it may have been destroyed or it was not existed at all. But the

fact that Japan occupied Manchuria and then North China and then

greater part of China and then Pearl Harbor Incident still remain... I

cannot prove that it is a true [document], but at the same time I also

have no means to disprove it... If Tanaka Memorial was untrue, was cooked up, everything predicted in it has been carried out."}

|

II

Many Japanese leaders have spoken and written in support of the plans of conquest set forth in the Tanaka Memorial since it was first submitted to the Emperor in 1927.

For example, Lt. Gen. Kiyokatsu Sato wrote a book entitled "Japanese-United States War Imminent" (Japanese title: "Nichi-Bei Sen Chikashi"), in which he discussed in particular the importance of a Japanese attack on Hawaii. This book has been in print for several years. {NOTE: See this PDF file for an article from the Sunday Morning Star (April 7, 1940 issue). Read also this LIFE magazine article from Dec. 22, 1941, entitled "The Great Pacific War" (PDF file).}

The Special Committee on Un-American Activities obtained a translation of excerpts of the lieutenant general's book which read as follows:

The American people

have brought disgrace upon us Japanese who, with a

history of some 3,000 years, have never been subjected to any insult

from a foreign country.

No nation in the world respects honor to a higher degree than the Japanese. Small wonder, then, that the Japanese treat the Americans as their enemy. The two nations have not gone to war with each other, but the Japanese cannot possibly bring themselves to regard the Americans as their friends.

Some Japanese are inclined to think that Commodore Perry was a benefactor to Japan on the ground that he opened the country to foreign intercourse toward the end of the Tokugawa shogunate. This is an utter mistake.

Perry did not come to these shores to form a friendship with this country. According to the various documents he dispatched to his Government, he had visited Japan with intent to occupy it.

It was the Americans who manifested considerable displeasure at Japan's advance to East Asia. They have subjected us to manifold indignities.

When and where a Japanese-American war will be fought we cannot say. If the United States of America carries out her traditional China policy to a full extent, then she is bound to clash with Japan sooner or later on the China question which is vital to the existence of this country.

We shall have to settle the question by force of arms, if diplomatic negotiations fail.

This brings us to a consideration of a possible war with America. No matter from what motives hostilities may come to be opened, or whether we assume the offensive or the defensive, there can be no doubt that Hawaii will be the most important strategic point in a war between America and Japan.

Success or failure in the struggle for this strategic point will prove a decisive factor in the war. With the Hawaiian Islands as her base of operations, America could bomb Tokyo or Osaka without much difficulty, provided she uses airplanes and airships of superior quality.

While Hawaii is an American possession, Japan would have to remain on the defensive. But if, on the contrary, Japan occupies the islands, her fleet would find itself in a position not only to assume the offensive, but also to bomb the cities on the west coast of America.

In a war with America, therefore, we must at all costs, even with a sacrifice of a few vessels, take possession of Hawaii. The distance between Hawaii and the American continent is a little smaller than that between the islands and Japan. This would mean that at the outbreak of hostilities the American fleet or fleets of warships would be able to get to the islands before the Japanese, insofar as both fleets have the same speed. For this reason our navy must needs possess ships far speedier than America.

If the main squadron of America were in the Hawaiian waters at the outbreak of war, then a clash between the American and Japanese main fleets would have to take place somewhere between the islands and Yokohama. Should our navy emerge victorious from this battle, it would be able to occupy Hawaii, and its subsequent operations would be facilitated.

The opposite result of this battle would compel the Japanese Navy to remain on the defensive and would render its operations extremely difficult. The great thing is, therefore, for Japan to see that hostilities are opened before the main strength of the American Fleet is brought to Hawaii and that her naval operations take place with lightning speed.

The struggle for Hawaii thus constitutes the first stage of a Japanese-American war. On the assumption that Hawaii was captured by our navy, the Japanese forces would undertake, as the next step, the task of destroying the Panama Canal and the main squadron of America.

If the Japanese Navy succeeded in crushing the American Fleet in the Pacific, landing on the Pacific coast of America would become easy.

At the same time the Panama Canal must be destroyed, as the maintenance of traffic through it would facilitate replenishment of the American Navy.

Attacks should be made on the Canal by an effective air fleet. The destruction of the Canal and the American Fleet would literally be half the battle. Thus would end the second period of the war.

The third period would begin with a landing of Japanese forces on the western coast of the American continent and the work of destroying the cities and naval ports on the west coast.

The next course would be to form the main line of defense along the Rocky Mountains, so that our military troops might be massed in the occupied areas along the coast.

Preparations made west of the Rockies, our army would now take the offensive and advance toward the east coast. This would usher in the fourth and the last period of the war.

Each period would probably last several years; the third and the fourth periods would last the longest. Thus the war would last at least 4 or 5 years; it might even drag out to last several score years. If and when Japan, forestalled by America, finds it impossible to occupy Hawaii, her navy would see the wisdom of deferring a decisive battle with the American ships till full preparations are completed.

Meanwhile, our coast might be subjected to bombardment and the main cities to attacks from the air. Our army would have to defend the coast facing the Pacific and stave off the enemy's landing, while our flotillas of destroyers and submarines would watch for an opportunity of attacking the enemy's capital ships.

When thoroughly ready, our main squadron would go forth and battle decisively with the enemy's. A victory for the Japanese Navy would naturally be followed by the capture of Hawaii and other operations, as described before.

Whether Japan acts on the offensive or on the defensive, a war with America would certainly be a protracted one involving much sacrifice and demanding the united efforts and indomitable perseverance of the nation as a whole.

During the Meiji era Japan fought China on the Korean question and Russia on the Manchurian question. And now it looks as though she were going to fight America on the China question. Such seems to be the fate to which this country is predestinated.

The China question is, as already said, a question of life and death to us. Japan can no longer remain "cabined, cribbed, and confined," as of yore, within her island empire. She needs expansion to the Asiatic continent, which is her "life line."

It is a luxury for America to exercise capitalistic imperialism in China and to attempt to bring that vast territory under her economic domination.

America still has vast areas in her own territory that have to be brought under cultivation. She has considerable quantities of natural resources still to be developed.

She has Canada to her north and Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina to her south, where she can find markets for her goods.

Why should America, then, attempt to practice imperialism on a continent some 5,000 miles distant, across the Pacific, from her own?

No nation in the world respects honor to a higher degree than the Japanese. Small wonder, then, that the Japanese treat the Americans as their enemy. The two nations have not gone to war with each other, but the Japanese cannot possibly bring themselves to regard the Americans as their friends.

Some Japanese are inclined to think that Commodore Perry was a benefactor to Japan on the ground that he opened the country to foreign intercourse toward the end of the Tokugawa shogunate. This is an utter mistake.

Perry did not come to these shores to form a friendship with this country. According to the various documents he dispatched to his Government, he had visited Japan with intent to occupy it.

It was the Americans who manifested considerable displeasure at Japan's advance to East Asia. They have subjected us to manifold indignities.

When and where a Japanese-American war will be fought we cannot say. If the United States of America carries out her traditional China policy to a full extent, then she is bound to clash with Japan sooner or later on the China question which is vital to the existence of this country.

We shall have to settle the question by force of arms, if diplomatic negotiations fail.

This brings us to a consideration of a possible war with America. No matter from what motives hostilities may come to be opened, or whether we assume the offensive or the defensive, there can be no doubt that Hawaii will be the most important strategic point in a war between America and Japan.

Success or failure in the struggle for this strategic point will prove a decisive factor in the war. With the Hawaiian Islands as her base of operations, America could bomb Tokyo or Osaka without much difficulty, provided she uses airplanes and airships of superior quality.

While Hawaii is an American possession, Japan would have to remain on the defensive. But if, on the contrary, Japan occupies the islands, her fleet would find itself in a position not only to assume the offensive, but also to bomb the cities on the west coast of America.

In a war with America, therefore, we must at all costs, even with a sacrifice of a few vessels, take possession of Hawaii. The distance between Hawaii and the American continent is a little smaller than that between the islands and Japan. This would mean that at the outbreak of hostilities the American fleet or fleets of warships would be able to get to the islands before the Japanese, insofar as both fleets have the same speed. For this reason our navy must needs possess ships far speedier than America.

If the main squadron of America were in the Hawaiian waters at the outbreak of war, then a clash between the American and Japanese main fleets would have to take place somewhere between the islands and Yokohama. Should our navy emerge victorious from this battle, it would be able to occupy Hawaii, and its subsequent operations would be facilitated.

The opposite result of this battle would compel the Japanese Navy to remain on the defensive and would render its operations extremely difficult. The great thing is, therefore, for Japan to see that hostilities are opened before the main strength of the American Fleet is brought to Hawaii and that her naval operations take place with lightning speed.

The struggle for Hawaii thus constitutes the first stage of a Japanese-American war. On the assumption that Hawaii was captured by our navy, the Japanese forces would undertake, as the next step, the task of destroying the Panama Canal and the main squadron of America.

If the Japanese Navy succeeded in crushing the American Fleet in the Pacific, landing on the Pacific coast of America would become easy.

At the same time the Panama Canal must be destroyed, as the maintenance of traffic through it would facilitate replenishment of the American Navy.

Attacks should be made on the Canal by an effective air fleet. The destruction of the Canal and the American Fleet would literally be half the battle. Thus would end the second period of the war.

The third period would begin with a landing of Japanese forces on the western coast of the American continent and the work of destroying the cities and naval ports on the west coast.

The next course would be to form the main line of defense along the Rocky Mountains, so that our military troops might be massed in the occupied areas along the coast.

Preparations made west of the Rockies, our army would now take the offensive and advance toward the east coast. This would usher in the fourth and the last period of the war.

Each period would probably last several years; the third and the fourth periods would last the longest. Thus the war would last at least 4 or 5 years; it might even drag out to last several score years. If and when Japan, forestalled by America, finds it impossible to occupy Hawaii, her navy would see the wisdom of deferring a decisive battle with the American ships till full preparations are completed.

Meanwhile, our coast might be subjected to bombardment and the main cities to attacks from the air. Our army would have to defend the coast facing the Pacific and stave off the enemy's landing, while our flotillas of destroyers and submarines would watch for an opportunity of attacking the enemy's capital ships.

When thoroughly ready, our main squadron would go forth and battle decisively with the enemy's. A victory for the Japanese Navy would naturally be followed by the capture of Hawaii and other operations, as described before.

Whether Japan acts on the offensive or on the defensive, a war with America would certainly be a protracted one involving much sacrifice and demanding the united efforts and indomitable perseverance of the nation as a whole.

During the Meiji era Japan fought China on the Korean question and Russia on the Manchurian question. And now it looks as though she were going to fight America on the China question. Such seems to be the fate to which this country is predestinated.

The China question is, as already said, a question of life and death to us. Japan can no longer remain "cabined, cribbed, and confined," as of yore, within her island empire. She needs expansion to the Asiatic continent, which is her "life line."

It is a luxury for America to exercise capitalistic imperialism in China and to attempt to bring that vast territory under her economic domination.

America still has vast areas in her own territory that have to be brought under cultivation. She has considerable quantities of natural resources still to be developed.

She has Canada to her north and Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina to her south, where she can find markets for her goods.

Why should America, then, attempt to practice imperialism on a continent some 5,000 miles distant, across the Pacific, from her own?

III

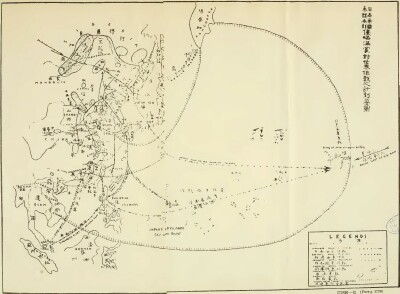

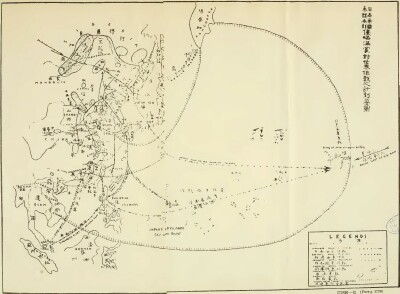

Early in 1941, the committee came into possession of a so-called strategic map which gave clear proof of the intentions of the Japanese to make an assault on Pearl Harbor.

(The following double page insert -- Exhibit No. 2 -- is a reproduction of the strategic map.)

EXHIBIT NO. 2

{NOTE: Click on image to enlarge. Resolution is limited due to quality

of the original document. Literal

translation of this map: "Japan Imperial General Staff Headquarters:

Map of World Operations Plan for the Invasion of

Manchuria

and

Mongolia." The "LEGENDS" box reads as follows:

Japanese Naval

Movement -- Enemies Naval Movement -- Japanese Army Movement -- Enemies

Army Movement -- Japanese Army -- Enemies Army -- Japan's Naval Sphere

of Influence.}

The strategic map was prepared by the Japanese Imperial Military Intelligence Department with a detailed plan of Japan's proposed conquest of the Far East and Hawaiian Islands.

This map is but another evidence of Japan's aggressiveness and her desire for world conquest. In the late Tanaka Memorial of July 25, 1927, to the Emperor of Japan, Premier Tanaka said, under the item of "General Policy":

* * * Japan cannot

remove the difficulties in Eastern Asia unless she

adopts a policy of blood and iron. But in carrying out this policy we

have to face the United States. * * * In the future if we want to

control China, we must first crush the United States just as in the

past we had to fight the Russo-Japanese War.

Again he said in the same Memorial, under the item ''The Necessity of Changing the Organization of South Manchuria Railway":

with such large

amounts of iron and coal at our disposal we ought to be

self-sufficient for at least 70 years. We shall have to acquire the

secret for becoming the leading nation in the world. Thus strengthened,

we can conquer both the East and West.

Japanese have been wont to say that Japan planned to conquer the world within 10 years after the Mukden Incident of September 18, 1931. The occupation of Manchuria and Mongolia is a necessary step for conquest of the Pacific. After North China has been acquired, the whole Pacific area can be absolutely under her control. The next step is to take over Guam, the Philippine and Hawaiian Islands, and even Hong Kong and India are included in this scheme.

According to the strategic map, Japan has almost accomplished the first part of her military conquest.

The strategic map shows that the line of the first conquest extends from Karafuto to Shantung Province, including Manchuria and Mongolia. It also shows that after she has accomplished the first step of this military occupation in Korea, Manchuria, Mongolia, and Shantung Province, she will have acquired a sufficient supply of material to enable her to mobilize forces and extend her power to Chekiang and Fukien Provinces, thus securing naval bases for future world conquest. Once well settled in Manchuria and Mongolia, she has iron deposits, estimated by Japanese experts at 1,200,000,000 tons; coal deposits, 2,500,000,000 tons; timber, 200,000,000 tons, which will last Japan 200 years, and many other resources, more than enough to enable Japan to wage war with England and the United States. According to Japan's military program, she will fight England in the north of the Philippine Islands and drive the British out of Asia, thus securing Hong Kong for the Japanese. A proposed naval battle between the United States and Japan is to give the latter Hawaiian Islands, then the Philippines and Guam must be under the control of Japan according to this military program. This will enable, as Tanaka has said, the enlarged Japan to become the leading nation of the world.

IV

Recently, the Japanese War Minister Araki published a signed article in the Records of the Marchers Club, an influential monthly among the Japanese reservists, under the title "Japan's Mission Under the Reign of Showa" (present Emperor of Japan). This essay was divided into 10 chapters. The most outspoken words in it are:

The imperialism * *

* a product of the fusion of the spirit in which

our Nation was founded and the great vision of our people, stands in

urgent need of being proclaimed to the corners of the "four seas" and

established in this world.

Japan means to carry out such "imperialism," for according to General Araki, "we must take decisive action to get rid of any obstacle in the way, even resorting to force." Chapter VII reveals --

* * * This

great vision was defined when Emperor Jimmu * * * issued

the imperial proclamation of his ascension to the throne in Kashibara,

Yamato * * * after his conquest of the eastern barbarians. The

proclamation read: "To accept with regard to the past, the mission of

our ancestors to give life to the state and greatly to nourish and

increase with regard to the future. In accordance with our imperial

ancestors' ambitions, I now establish my capital to conquer the whole

world and embrace the whole universe as our state." Now to fulfill the

vision "to conquer the world and embrace the universe as our state" so

as to pacify the Emperor Jimmu's desire "greatly to nourish and

increase" has been our traditional policy * * * The Manchurian

incident, viewed in this light, has very great significance. Under the

direction of Heaven, Japan has put forward the first step.

Concluding Chapter VI, Araki remarks:

When we observe

carefully, no other country has a culture with the

spirit of our imperialism. Countries in eastern Asia are objects of the

white man's oppression. Awakened Japan, however, cannot allow this. If

actions of any of the powers are not conducive to our imperialism, our

blows shall

descend on that power. This is the mission of our imperialism * * *

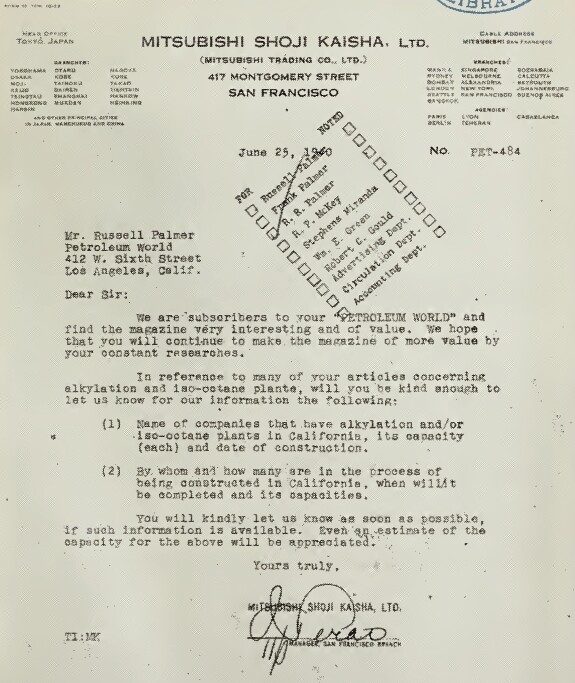

"Once hostilities begin, our first move will be an attack upon the Panama Canal. * * * We have submarines capable of traveling 10,000 miles without refueling. * * * The Midway Islands can be taken within 1 day; then we must attack Hawaii. * * *" These statements and many others of the same tenor appear in a book published in Tokyo in October 1940 entitled "The Triple Alliance and the Japanese-American War" by Kinoaki Matsuo. {NOTE: This book was translated by Kilsoo Haan and published in April 1942 under the title "How Japan Plans to Win." See this excerpt of Chapters 11 and 12, and also the article from the Milwaukee Journal (Dec. 28, 1941 issue). For more on Haan's efforts, see this compilation of letters. It should be noted that the primary source on this information here and elsewhere in this report can be found in this News Research Service Newsletter of July 16, 1941.}

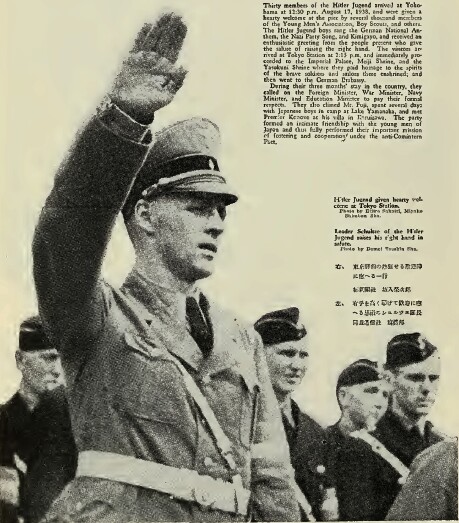

In December 1940, a retired Japanese naval captain, Otojiro Endo, and a retired Japanese Army major, Masichi Sugihara, visited Pacific Coast States in America and held secret meetings with leaders of Japanese-American citizens. Purpose of the tour was to inspire courage among sabotage and espionage agents, and to recruit new men for the Japanese-American Trojan horse brigade. In their discussions, frequent use was made of the book, The Triple Alliance and the Japanese-American War. A few copies of this volume were given out, only to the most trusted leaders. The committee succeeded in obtaining one of these; a translation was made, and even the most casual perusal suggests immediately that this is a textbook for Japanese espionage.

The table of contents in itself is most revealing. Following are the translated chapter headings and subtitles, as they appear in the table of contents:

I. Crucial moment

for Japan and America:

(1) The China

incident and the United States.

(2) Pacific War -- A hard struggle.

(3) The Second World War and the United States.

(4) The United States and Canada.

II. Expansion of the American Fleet:(2) Pacific War -- A hard struggle.

(3) The Second World War and the United States.

(4) The United States and Canada.

(1) Illusioned

America.

(2) Battleships in construction.

III. History of the Japanese-American struggle:(2) Battleships in construction.

(1) The first

anti-Japanese question.

(2) United States, Japanese, and Manchurian conflict.

(3) Imperialistic foreign diplomacy of United States.

(4) Long-delayed destruction of London Conference.

IV. United States-Japan War inevitable:(2) United States, Japanese, and Manchurian conflict.

(3) Imperialistic foreign diplomacy of United States.

(4) Long-delayed destruction of London Conference.

(1) United

States-Japan friendship a delusion.

(2) Pacifists and the fear of the American question.

(3) United States-Japan War costs.

V. United States naval strength:(2) Pacifists and the fear of the American question.

(3) United States-Japan War costs.

(1) United States

capital ships.

(2) United States cruisers.

(3) United States destroyers.

(4) United States aircraft carriers.

(5) United States submarines.

(6) United States naval bases.

(7) United States present military strength.

(8) United States naval developments.

VI. New United States weapons and mechanized units:(2) United States cruisers.

(3) United States destroyers.

(4) United States aircraft carriers.

(5) United States submarines.

(6) United States naval bases.

(7) United States present military strength.

(8) United States naval developments.

(1) New United

States weapons.

(2) Fear of chemical warfare.

VII. The great air force of the United States:(2) Fear of chemical warfare.

(1) Brief sketch of

United States Air Force.

(2) Present United States Air Force.

VIII. War plans of the United States:(2) Present United States Air Force.

(1) United States

plans for attack.

(2) United States plans attack on western Pacific.

IX. Immediate war versus prolonged war:(2) United States plans attack on western Pacific.

(1) Immediate

American war decision.

(2) Immediate Japanese war decision.

X. Time of conflict:(2) Immediate Japanese war decision.

(1) Lightning

military movements.

XI. Japan's attack on the Philippine Islands:(1) The Philippine

and Asiatic Fleet.

(2) Occupation of Guam by the Japanese Fleet.

XII. The fall of Manila:(2) Occupation of Guam by the Japanese Fleet.

(1) Japan's flag

hoisted in the Philippine Islands.

XIII. Fear of destruction of foreign trade:(1) Japan plans

foreign trade destruction.

XIV. Singapore and Hong Kong:(1) Problem of

Singapore Army base.

(2) What becomes of Hong Kong?

XV. The United States Fleet in Hawaii:(2) What becomes of Hong Kong?

(1) Pacific battle

force and military strength.

(2) Entire fleet concentrates at Pearl Harbor.

XVI. Japan's surprise fleet:(2) Entire fleet concentrates at Pearl Harbor.

(1) United States

plans for crossing the ocean.

(2) Activities of the surprise fleet.

XVII. American naval expedition to Japan.(2) Activities of the surprise fleet.

(1) Japanese

expedition.

(2) Destruction of United States Fleet.

(3) Movement of Japan's fleet.

XVIII. United States Air Force attacks Japan:(2) Destruction of United States Fleet.

(3) Movement of Japan's fleet.

(1) United States

bombing of Japanese cities.

(2) Defense against air attack.

XIX. United States-Japanese great battle in the Pacific:(2) Defense against air attack.

(1) Attacks of

United States capital ships.

(2) Withdrawal of United States Fleet.

XX. Occupation of Hawaii and closing of Panama Canal:(2) Withdrawal of United States Fleet.

(1) Japanese

occupation of Hawaii.

(2) Japanese closing of Panama Canal.

XXI. Japan-Germany-Italy alliance and the United States:(2) Japanese closing of Panama Canal.

(1) Establishment of

the triple alliance.

(2) The meaning of the alliance.

(2) The meaning of the alliance.

THE JAPANESE

SURPRISE FLEET

Under that subtitle, the author of the book revealed Japan's plans to employ long-range submarines on the American side of the Pacific, and to take and use the Midway Islands as a submarine base:

Chapter 17, page 279.

-- In the future, our submarines must be able to

operate alone in the west Pacific; their ability to attack, and to make

long journeys, is vitally important. Submarines which can travel 10,000

miles could easily cross the Pacific. There are very small type subs

which could accomplish a lot on the American side of the Pacific.

Our navy will quickly occupy the Midway Islands, and a submarine base will be established at once. It is only 1,160 miles to Hawaii, a very convenient distance for our surprise fleet. To this surprise fleet belong * * * mine layers of type * * * model 21. This type is capable of carrying a heavy load of mines for distribution in American sea routes of merchantmen and battleships. We can then strike the enemy fleet at a most opportune time, and cut off communication lines as well as merchantmen. [Editor's note: The number and type of mine layers are not given in the original text.]

Our navy will quickly occupy the Midway Islands, and a submarine base will be established at once. It is only 1,160 miles to Hawaii, a very convenient distance for our surprise fleet. To this surprise fleet belong * * * mine layers of type * * * model 21. This type is capable of carrying a heavy load of mines for distribution in American sea routes of merchantmen and battleships. We can then strike the enemy fleet at a most opportune time, and cut off communication lines as well as merchantmen. [Editor's note: The number and type of mine layers are not given in the original text.]

In discussing "Japanese Occupation of Hawaii," the book predicted that a Japanese naval victory would be sufficient incentive for the Japanese in Hawaii to immediately organize a volunteer army:

Chapter 21, pages 322-324.

-- In the Japanese occupation of Hawaii,

cooperation between army and navy is most important. The Midway Islands

must be taken before we attack Hawaii, for they would give us a good

foothold. It will be very easy to take Midway Islands, which

are

practically defenseless; in fact, it would require only about 1 day's

bombardment to take them.

In Hawaii, there are about 150,000 Japanese, one-half of whom are Nisei (Japanese descendants of foreign citizenship). Once the news of Japanese naval victories reaches Hawaii, the Japanese there will quickly organize a volunteer army. There is no doubt but that Hawaii will come into our hands.

In Hawaii, there are about 150,000 Japanese, one-half of whom are Nisei (Japanese descendants of foreign citizenship). Once the news of Japanese naval victories reaches Hawaii, the Japanese there will quickly organize a volunteer army. There is no doubt but that Hawaii will come into our hands.

Of course, the Japanese strategists devoted much thought to the Panama Canal. Under the subtitle, "Closing the Panama Canal," they said:

Chapter 21, pages 330-332.

-- The remaining question is: What will

become of the Panama Canal? Panama is a little over 4,600 knots from

Hawaii and about 8,000 knots from Japan, so an attack is not an easy

matter, and will require a considerable navy force. If, at the outbreak

of war, we proceed immediately to attack and close the Canal, we could

cut off the Atlantic from the Pacific. It would prove an invaluable

asset to our war strategy.

If the Panama Canal falls into Japanese possession and there is another Japan-America war, the United States will certainly strike at Panama; however, while Japan controls this area, the American Fleet will be divided -- one part in the Pacific, the other in the Atlantic -- and the two fleets cannot combine. American imperialism depends upon the strength of her navy, for without it her imperialistic ambitions cannot be realized. Once we control the Canal, we can enforce peace. Besides this, it will bring to an end American threats against Mexico and all other small nations in Central and South America.

Japanese possession of the Panama Canal has a direct bearing upon future peace; therefore, by all means, Japan must take the Canal and keep it even after the war. However, inasmuch as Panama is fortified, it will not be easy to take.

If the Panama Canal falls into Japanese possession and there is another Japan-America war, the United States will certainly strike at Panama; however, while Japan controls this area, the American Fleet will be divided -- one part in the Pacific, the other in the Atlantic -- and the two fleets cannot combine. American imperialism depends upon the strength of her navy, for without it her imperialistic ambitions cannot be realized. Once we control the Canal, we can enforce peace. Besides this, it will bring to an end American threats against Mexico and all other small nations in Central and South America.

Japanese possession of the Panama Canal has a direct bearing upon future peace; therefore, by all means, Japan must take the Canal and keep it even after the war. However, inasmuch as Panama is fortified, it will not be easy to take.

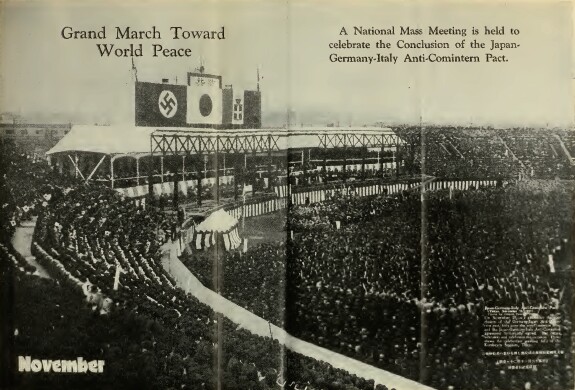

The "Meaning of Triple Alliance" carried a threat as to what America might expect as the result of a united attack from Japan, Germany, and Italy:

Chapter 22, pages 350-351.

-- The purpose of the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo

alliance is to secure the best possible cooperation in dealing with all

kinds of military, political, and economic problems, and to assist one

another in the strongest sense of the word. Should America become

involved in the war, she would be subjected to a gigantic united attack

by Japan, Germany, and Italy.

Only the flag of the sun, which symbolizes our nation, would fly over the Pacific. On the Atlantic, the swastika, which also symbolizes the sun and life, will be active with might. In addition, the meaningful flag of Italy would flash. In the face of all this, if America comes against Japan and tries to block her, it would be no more than a pin prick.

Only the flag of the sun, which symbolizes our nation, would fly over the Pacific. On the Atlantic, the swastika, which also symbolizes the sun and life, will be active with might. In addition, the meaningful flag of Italy would flash. In the face of all this, if America comes against Japan and tries to block her, it would be no more than a pin prick.

V

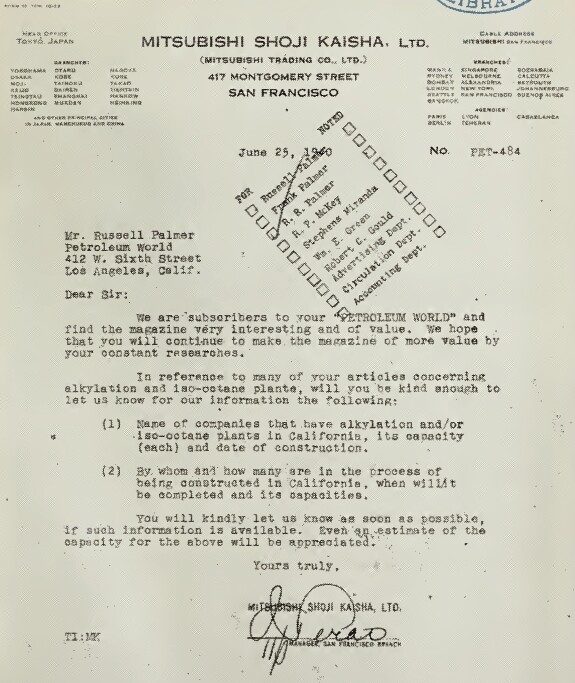

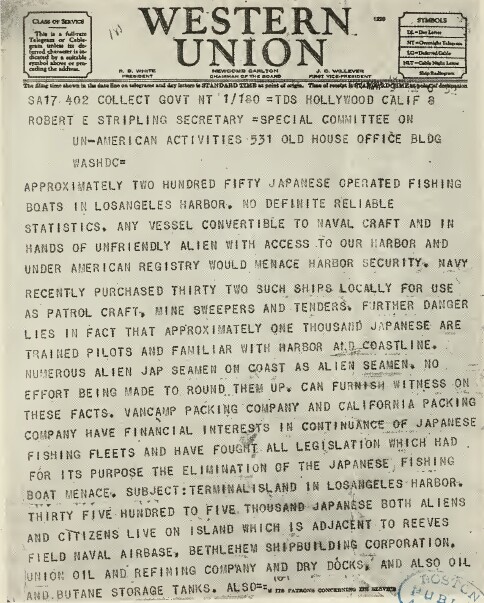

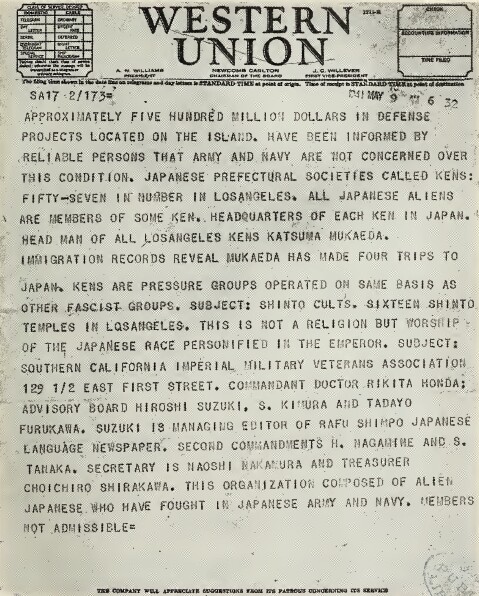

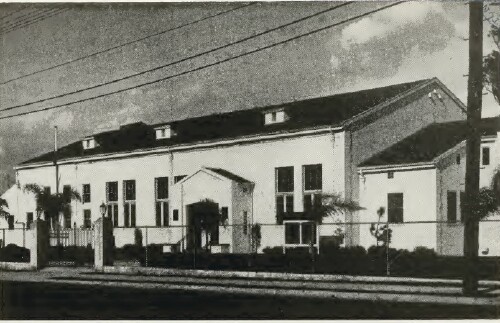

On October 26, 27, and 28, 1941, committee investigators and informers learned some interesting facts during their rounds of Little Tokyo in Los Angeles. Among other things, they obtained information which they embodied in the following telegram which they sent to the committee in Washington on October 30:

Have reliable

information that files of Board of Tourist Industries,

Japanese Government Railways, and Japan Tourist Bureau, Japanese

Government, and Domei News Service are being transferred to Japan on

Tatuta Maru

{Tatsuta Maru} scheduled to depart from San Francisco Sunday November

2.

Files are being handled in part by American Express Co. and will be

stored on San Francisco docks until departure of Tatuta Maru. Please

advise whether or not you desire us to subpoena the aforementioned

files.

The committee's investigators also learned that some 300 members of the Japanese community, including such persons as the officials of the Japan Tourist Bureau and the Domei News Service (both Japanese Government agencies), were holding farewell parties preparatory to their departure for Japan. They were scheduled to sail from San Francisco on the liner Tatuta Maru, on the November 30 sailing of that Japanese vessel, and the committee's investigators so informed the committee in Washington.

The taking of these extraordinary measures seemed to indicate that some decisive step in Japanese-American relations was about to be taken by the Japanese Government. It was on the basis of this assumption that the committee's investigators sent their information to Washington. Agencies of the executive branch of the United States Government were in possession of the same information.

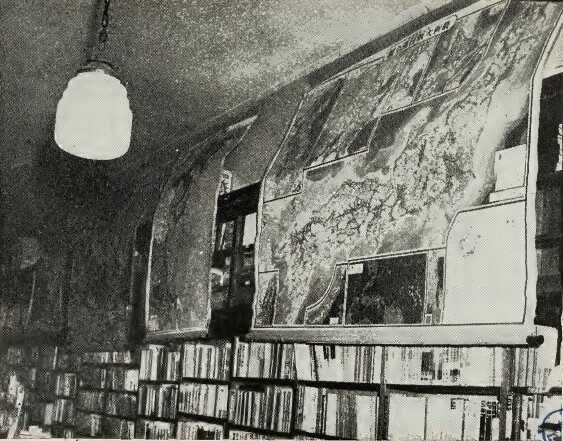

Long before Pearl Harbor, the Japanese had obtained possession of the most detailed and secret information concerning American bases, the American fleet, and other matters of the greatest strategic importance. Thousands of Japanese citizens, as well as thousands of American-born Japanese (Nisei), had traveled for years throughout the Pacific area gathering bits of information here and bits of information there. These agents of espionage forwarded this information through consulates and by means of couriers to the headquarters of the Imperial Navy in Tokyo. There it was assembled, analyzed, and given final comprehensive interpretation for use in the coming attack upon the United States.

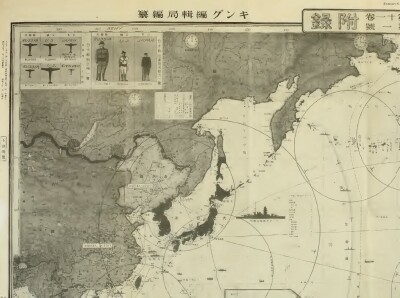

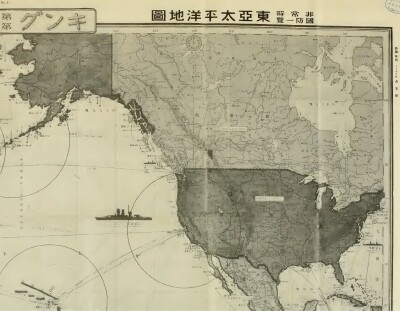

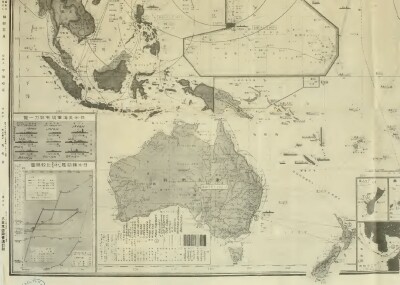

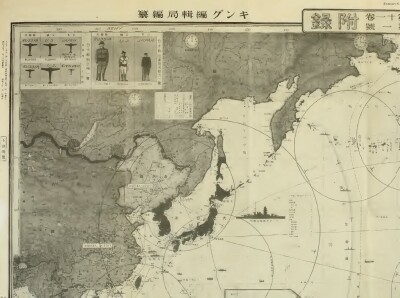

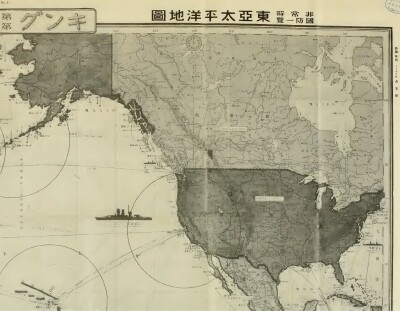

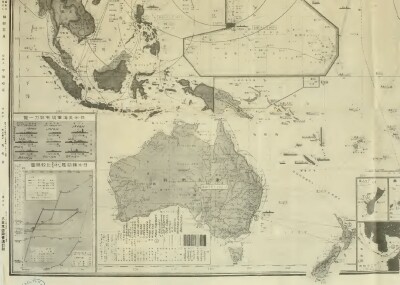

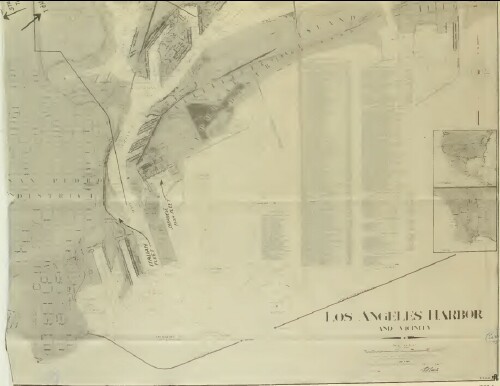

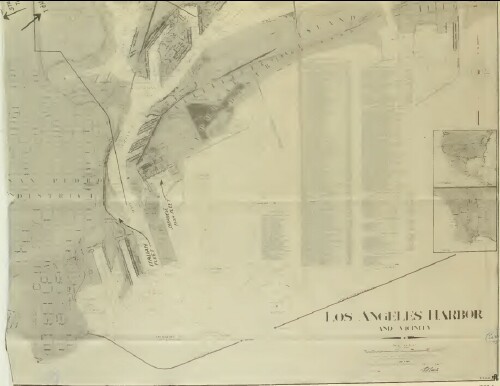

One highly significant compilation of such information was prepared in the form of a map of the entire Pacific area. (A reproduction of this map slightly reduced in size is inserted and folded opposite this page, as exhibit No. 3.) This map in turn was placed in the hands of all those who were to play a part in the coming war. Agents of the committee obtained a copy of this map under extraordinarily difficult circumstances. The committee's study of the map furnished convincing proof of Japan's belligerent intentions. That study also provided a clue to the Japanese strategy as it affected the places marked for assault.

EXHIBIT NO. 3

{NOTE: This map, entitled "Map of East Asia Pacific: Emergency National

Defense Summary," was published in Japan in 1935. See also this Sept. 7, 1940 Daily News article on military strengths and US strategy in the Pacific region. View this 1942 map of Japan's colonial expansion, naval battles, and sinkings on the West Coast.}

The large circle around the Hawaiian Islands indicates the radius of the patrol of the United States Navy. The small insert maps at the bottom of the large map are numbered. The numbers indicate the following: (1) Guam, (2) Pearl Harbor, (3) Manila, (4) Hawaiian Islands, (5) San Francisco Bay, (6) Panama in detail, (7) Panama City, (8) Colon, and (9) the Panama Canal.

It will be observed that the first four of the foregoing places have already been subjected to Japanese attack.

The map indicates the locations of United States air bases, mines, Army and Navy bases, ocean cables, canals, railroads, and radio stations. It also indicates the fleet positions and formations of the United States naval vessels.

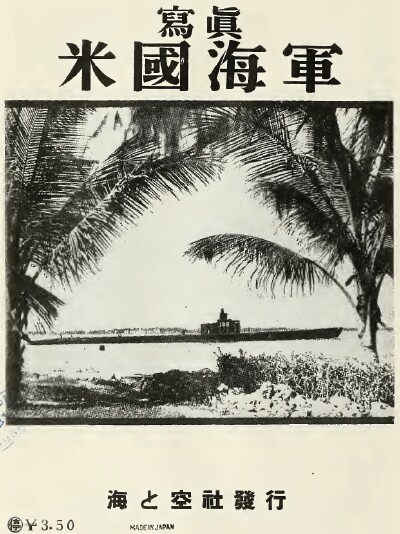

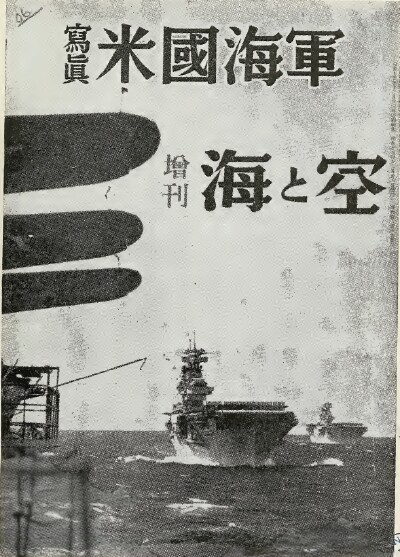

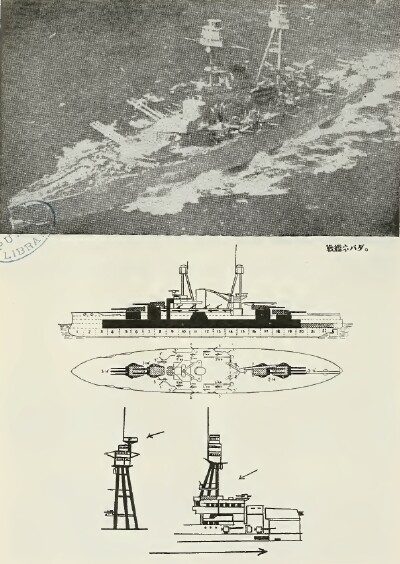

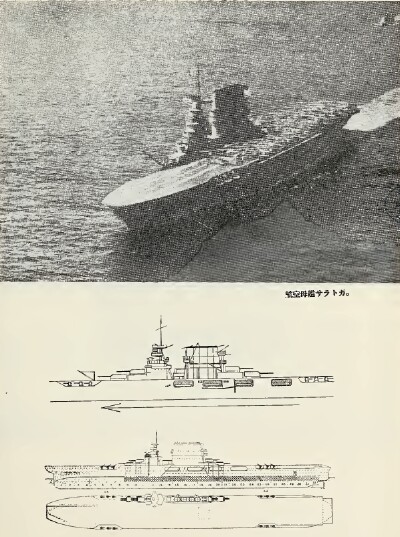

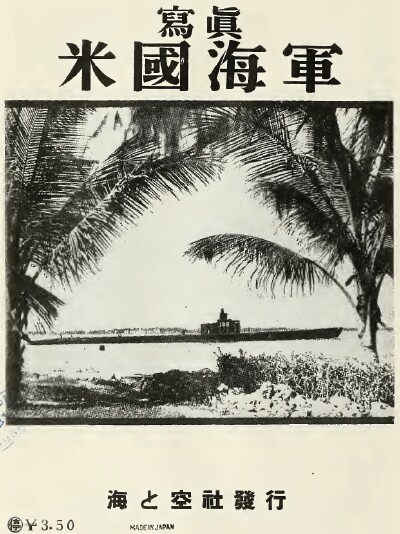

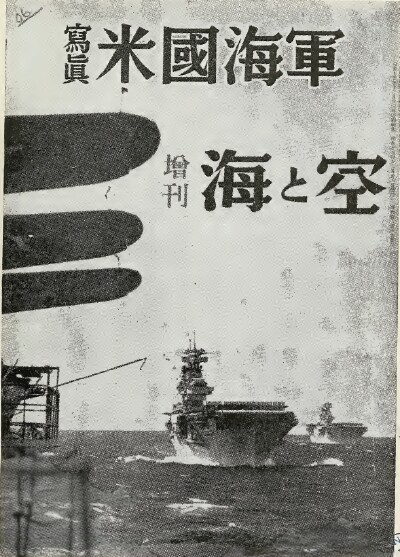

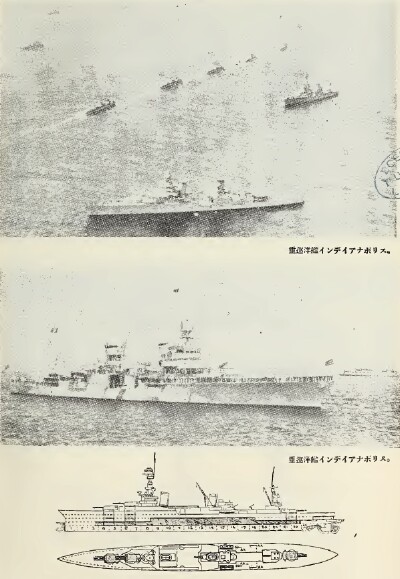

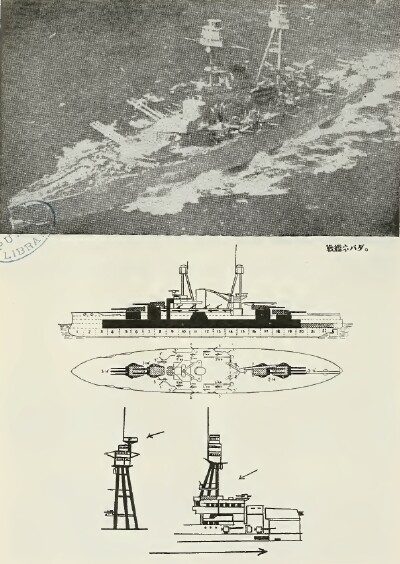

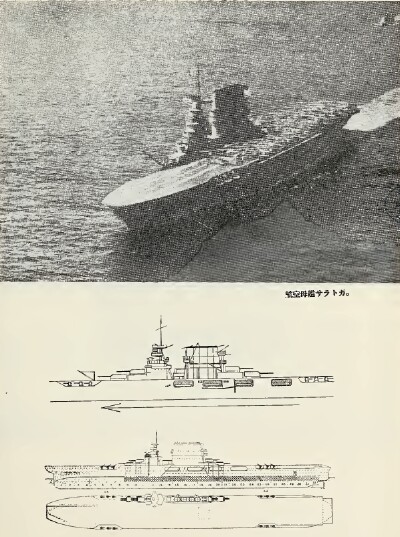

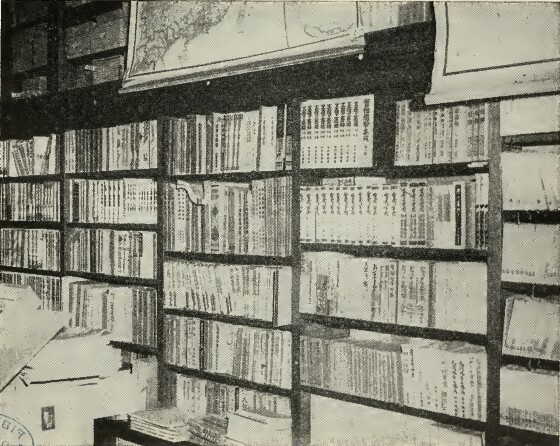

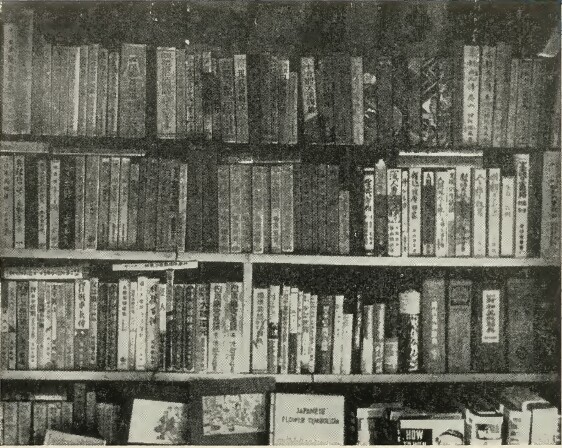

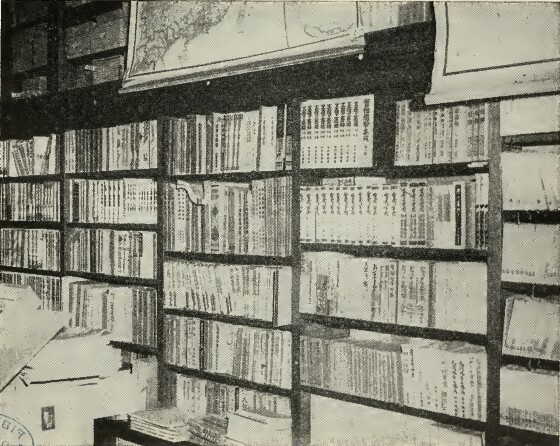

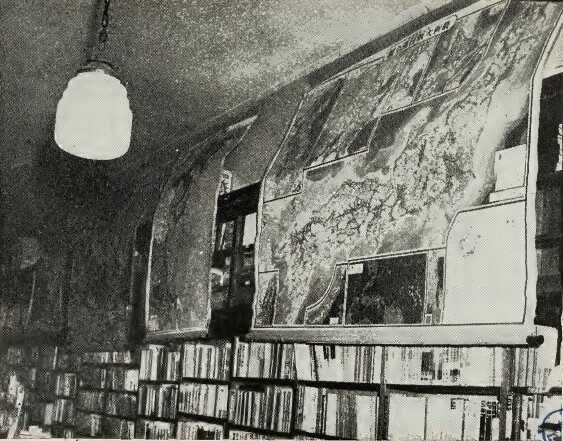

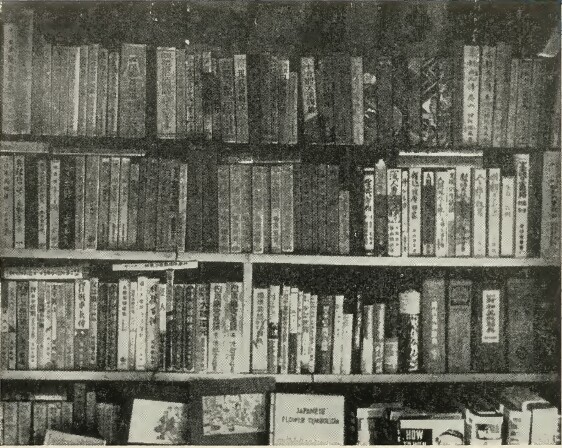

It is impossible to exaggerate the thoroughness with which the Japanese had studied the detailed construction of every vessel in the United States Navy. During the year before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Government had printed and circulated a handbook devoted exclusively to the naval vessels of the United States. The circulation of this 200-page book was naturally limited to those Japanese who were in a position to serve Japan by the possession of this highly important information. It was with great difficulty that the agents of the committee were able to obtain a copy of the volume.

The covers and four pages from the book are reproduced in the exhibits which follow.

Exhibit No. 4 is the front cover of this handbook.

Exhibit No. 5 is the back cover of the volume.

Exhibit No. 6 is a picture of the airplane carrier Saratoga.

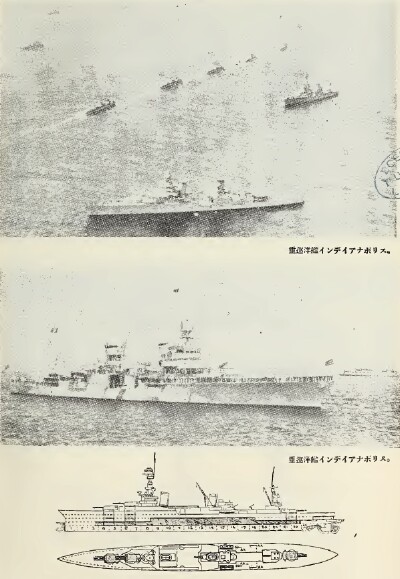

Exhibit No. 7 is a picture of the cruiser Indianapolis together with sketches of its construction.

Exhibit No. 8 is a picture of the Nevada together with sketches of its construction.

Exhibit No. 9 is a picture of the airplane carrier Saratoga together with sketches of its construction.

EXHIBIT NO. 4

EXHIBIT NO. 5

EXHIBIT NO. 6

EXHIBIT NO. 7

EXHIBIT NO. 8

EXHIBIT NO. 9

EXHIBIT NO. 5

EXHIBIT NO. 6

EXHIBIT NO. 7

EXHIBIT NO. 8

EXHIBIT NO. 9

It was the committee's purpose to show in the proposed September hearings something of the pains to which the Japanese Government had gone to familiarize the members of the Imperial Japanese Navy, and others who were to participate directly in the attack on the United States, with the entire fleet of the United States Navy. Through witnesses who were competent to testify on the subject, the committee intended to reveal the extent and efficiency of the vast Japanese espionage system which had been able to gather such strategic information concerning the United States Navy and other matters vital to the defense of this country.

The case of Commander Itaru Tatibana {Tachibana} and Torzichi {Toraichi} Kono, Japanese espionage agents, illustrates one of the Nipponese Government's methods of obtaining important United States naval data. {NOTE: For more information on Tachibana, see IA153, IA021, IA120 and IA060.}

Tatibana was registered at the University of Southern California as a student. Kono was for 18 years secretary and valet to Charlie Chaplin.

Working through an ex-yeoman of the United States Navy, Tatibana and Kono obtained highly important and secret data on naval matters. During the first half of 1941, this ex-yeoman of our Navy was financed by the two Japanese espionage agents in making two trips to Pearl Harbor where, by reason of his former connection with our Navy, he was able to make contacts with men who were carrying out secretarial duties aboard the U. S. S. Pennsylvania, flagship of the United States Fleet. In this way, the Nipponese spies were able to obtain and to communicate important data to Tokyo.

In this Japanese handbook on the United States Navy, the photographs of the various naval vessels of this country are usually accompanied by detailed sketches representing both the horizontal and the perpendicular view of the ship. Likewise in most cases the vessels were actually photographed in such a way as to give both aerial and horizontal views.

Proof that this handbook was an up-to-date publication is seen in the fact that it contains detailed drawings of the battleships North Carolina and Washington. The book also contains a map of the United States which marks the various Atlantic bases which this country recently acquired from Great Britain in connection with the lend-lease arrangements.

The sketches indicate the location of guns and the subsurface compartments.

One of the most important uses to which this handbook was put was the placing of it in the hands of Japanese fishermen up and down our Pacific coast. By thoroughly familiarizing themselves with the appearance and construction of every craft in the United States Navy, these fishermen were able to communicate important information concerning the movement of our warships to their superiors in the Japanese espionage department.

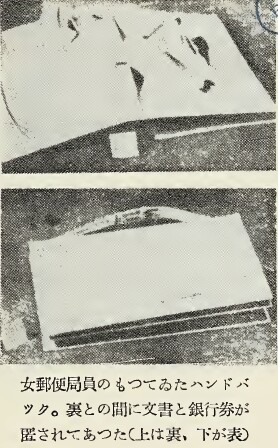

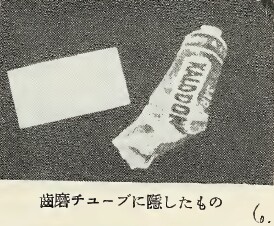

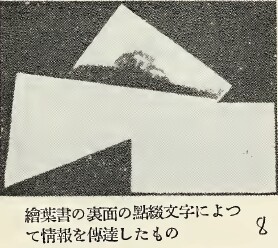

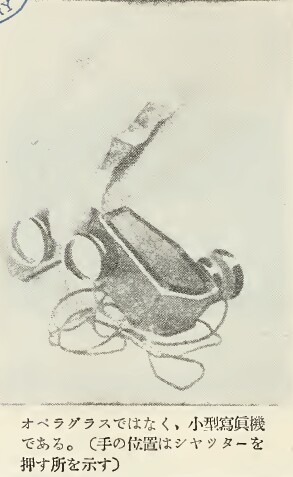

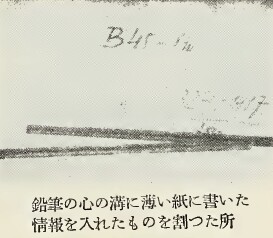

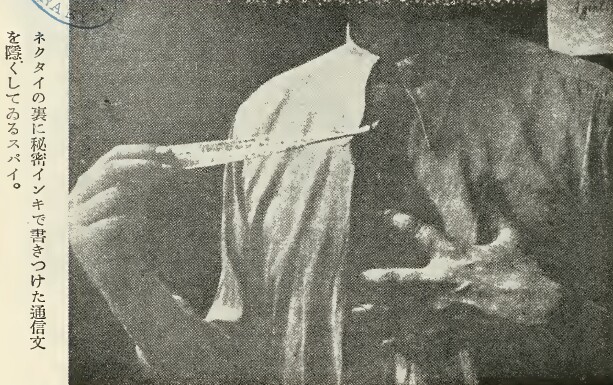

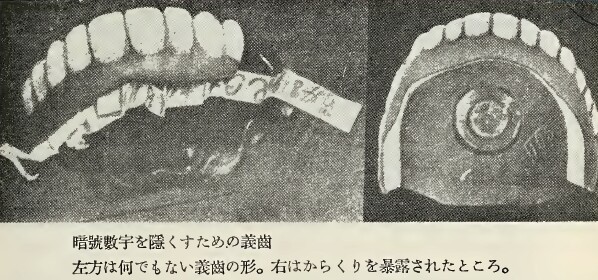

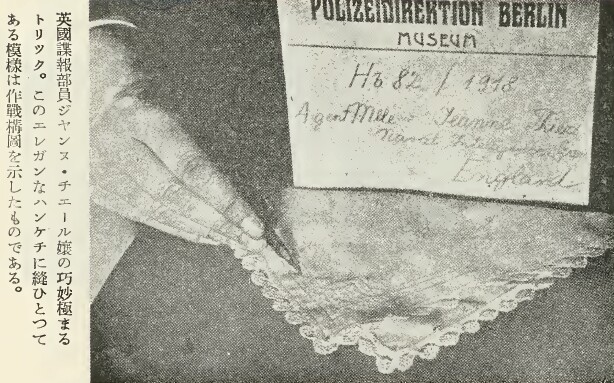

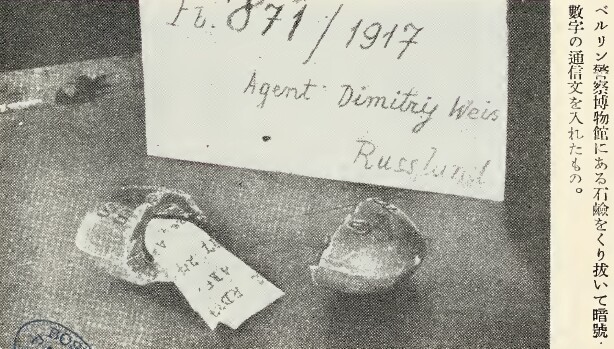

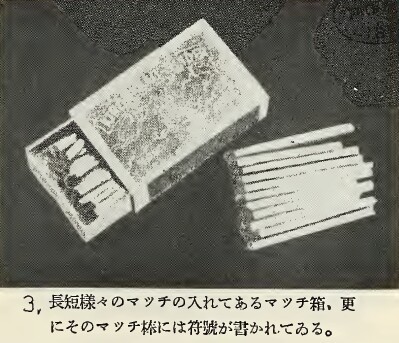

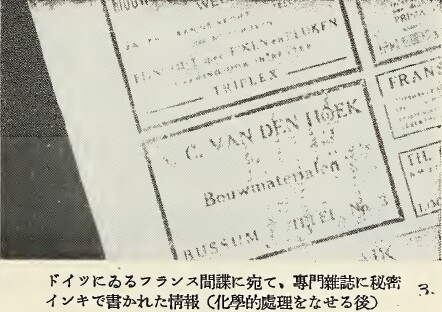

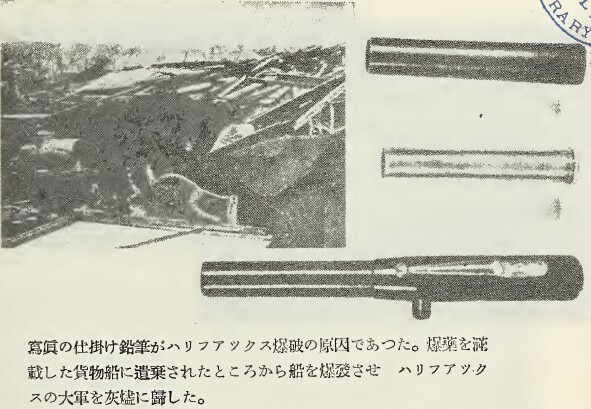

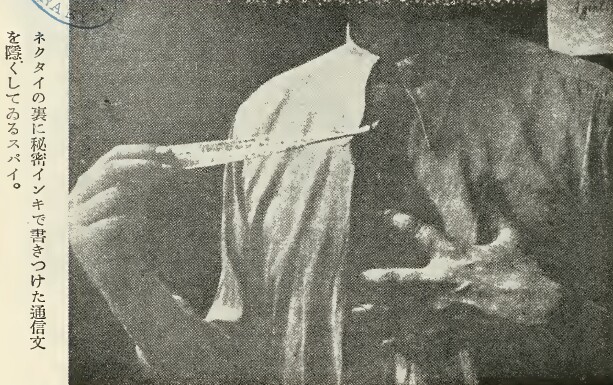

In February 1941, the Japanese Government made available to its agents in the United States a collection of illustrations of spy techniques. These were especially designed for the use of those who were engaged in any kind of courier service for the Japanese military intelligence.

The Japanese espionage system has been far flung. Due to the special psychology developed among the nationals of the totalitarian states, hundreds or thousands of these nationals (as well as their sympathizers of other nationality or citizenship) engage in the work of espionage, especially in some of the less hazardous work of supplying information to espionage headquarters. Japanese treaty merchants, Japanese fisherman, Japanese tourists, Japanese students, and in fact members of all categories of Japanese residing in the United States were commandeered -- often on a non-remunerative basis -- into the work of espionage.

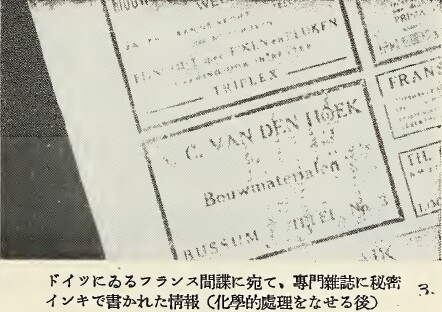

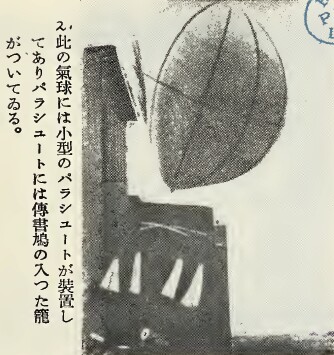

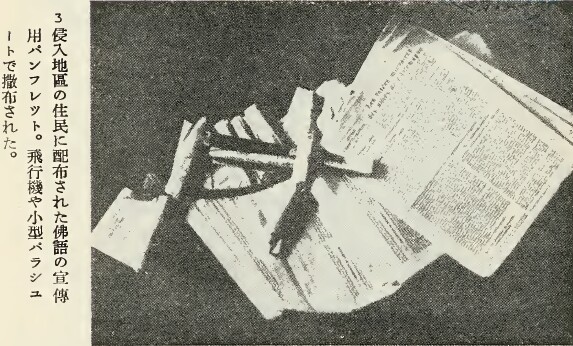

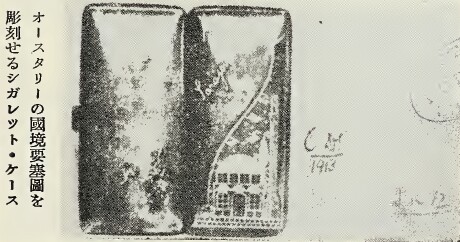

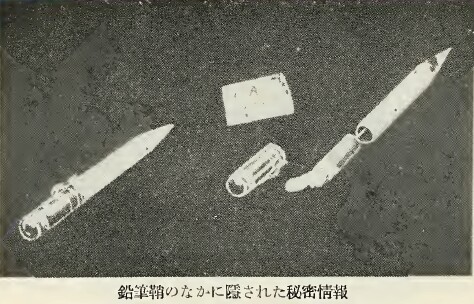

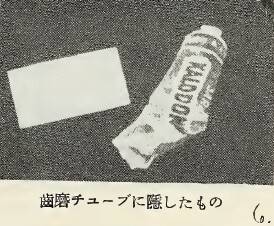

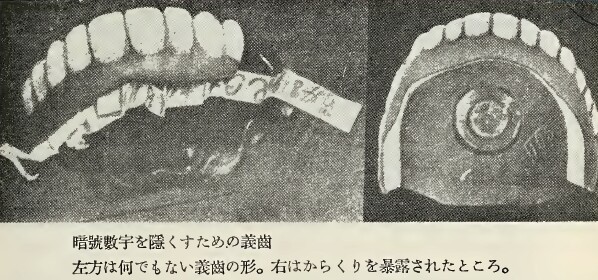

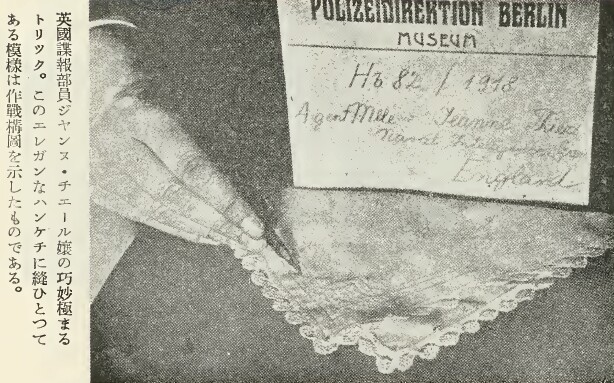

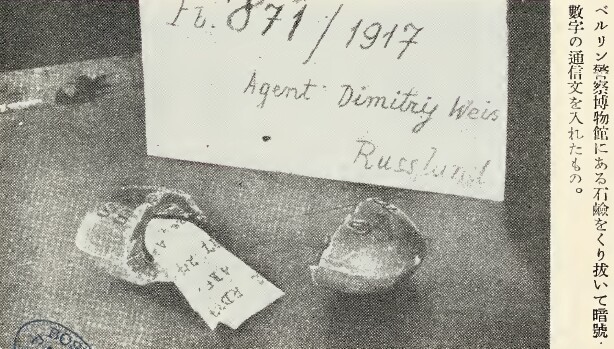

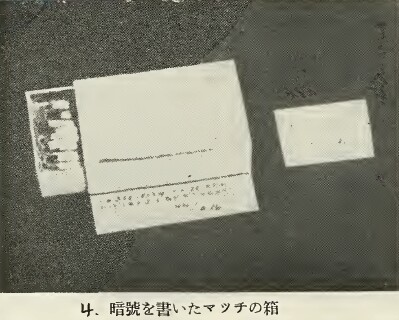

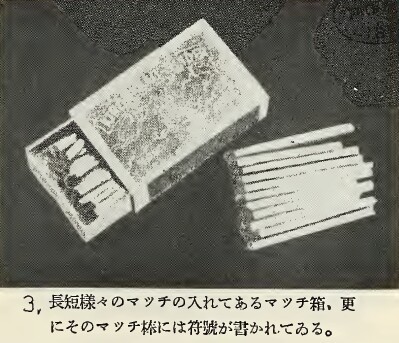

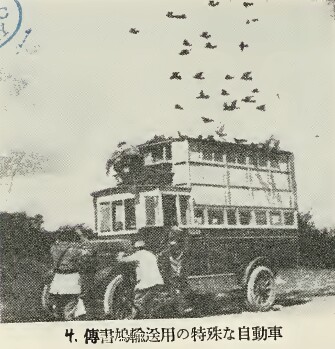

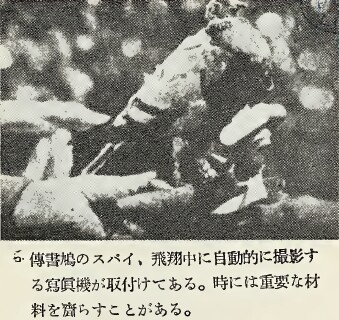

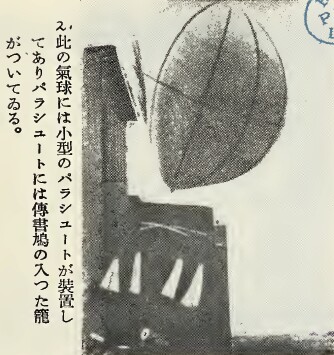

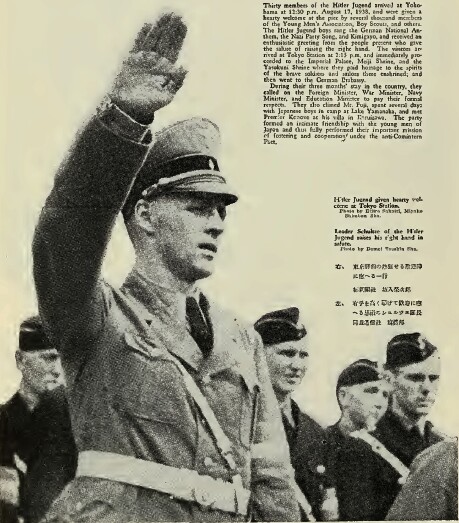

It will be noted from the exhibits which follow (exhibits 10 to 39, inclusive) that the Nazi espionage service was the probable origin of these illustrations of spy techniques. While the accompanying inscriptions are all in the Japanese language, the illustrations themselves are in many cases easily identified as of Nazi origin.

This collection of illustrations for spy techniques, obtained by the committee last year, is reproduced in the pages that follow in order that some light may be thrown on the way in which a vast amount of information has been transmitted by Japanese spies to their home government.

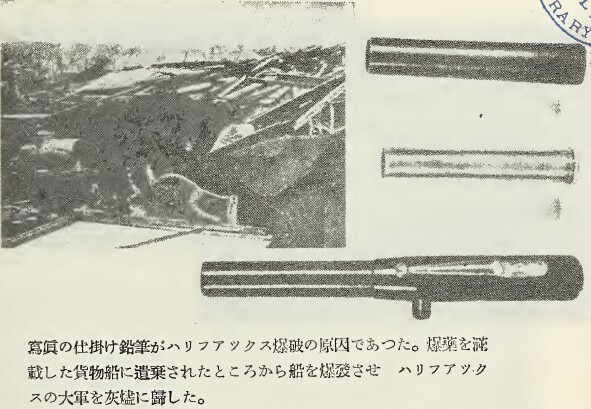

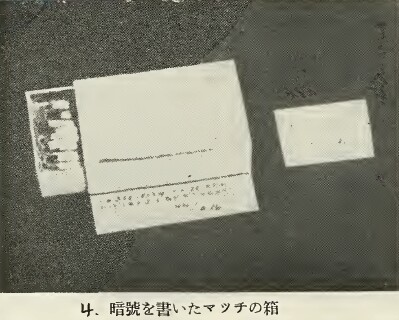

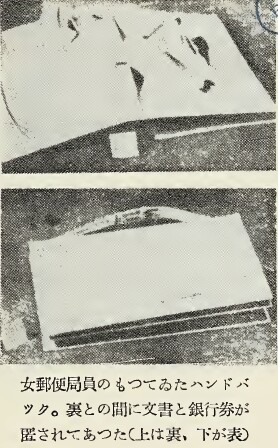

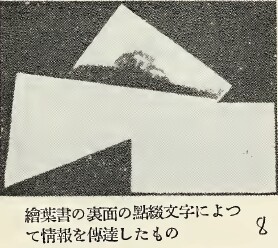

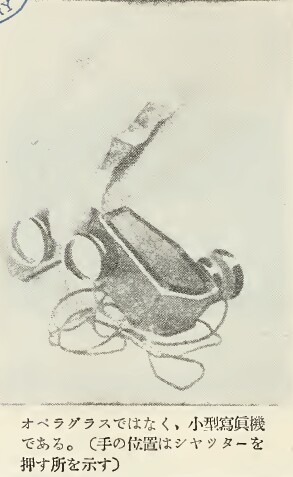

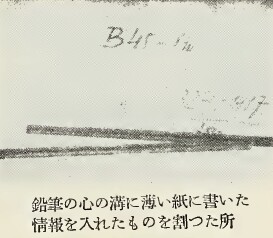

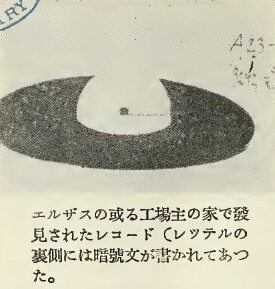

EXHIBIT NO. 10

This is a woman's handbag with a secret compartment for concealing documents. According to the Japanese inscription at the bottom, the handbag is for the special use of women post-office workers. The photograph above is of the interior of the handbag, and that below is of the exterior.

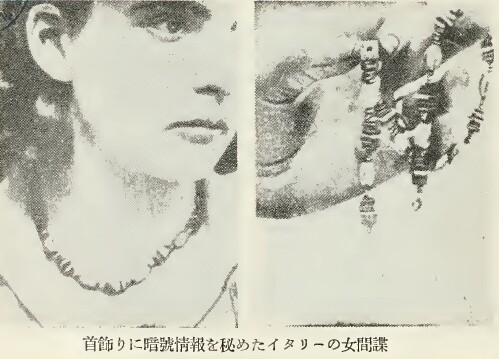

EXHIBIT NO. 11

This is a photograph of a woman who has a code message concealed in a necklace. In the picture at the right the bead which contains the code message is held between the thumb and the forefinger.

EXHIBIT NO. 12

Here are photographed a woman spy and her daughter who carry on their spy activities disguised as peasants.

EXHIBIT NO. 13

This is a photograph of Bernard Shaw's Devil's Disciple. Certain words in the volume are underlined in invisible ink. According to the Japanese inscription at the left, the spy must read page 45 of the book in order to decipher the code message.

EXHIBIT NO. 14

This is a secret letter cover and a tobacco catalog used in transmitting a code message.

EXHIBIT NO. 15

These are various views of a bar of chocolate which contains a secret code message.

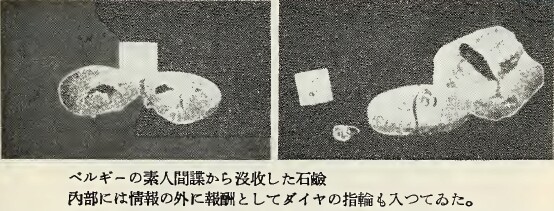

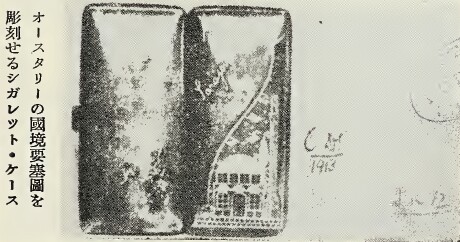

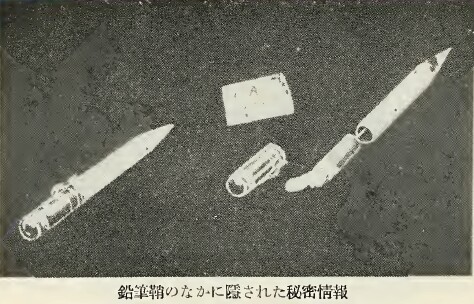

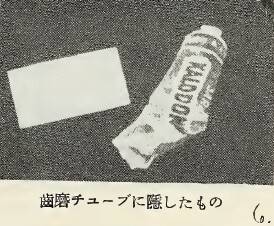

EXHIBIT NO. 16