米国日系人―疎開と移転

byWes Injerd

Table of Contents --- MULTI_SITE SEARCH

ホームページ日本語訳

DeepL Translator E>J>E 翻訳

| About half-way between the extreme pro

and con charges... is the true story of the Japanese evacuation and the

relocation centers in California. When the full story is told it will be filled with drama; with comedy and tragedy, with suffering and self-sacrifice, with villainy and heroism, with deep shadows and bright sunlight -- a story bewildering in its complexity of delicate problems. |

The Preservation of a People:

A Look at the Evacuation and Relocation

of the People of Japanese Ancestry

in the United States during World War II,

with extensive original source material,

transcribed in entirety,

from the papers of Dillon S. Myer,

Director of the War Relocation Authority,

and assorted documents from various

Intelligence and other Government Agencies.

transcribed in entirety,

from the papers of Dillon S. Myer,

Director of the War Relocation Authority,

and assorted documents from various

Intelligence and other Government Agencies.

This website is dedicated to a friend of mine, representative of the thousands of remarkable men who were like him. He was one of the brave soldiers of the renowned 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a Sergeant in the first division of the 100th Infantry Battalion, Company "D." He took part in the battles in the Vosges Mountains in northeastern France, at Bruyeres, in the Po Valley, and in the Rhineland, for which he and his comrades were given numerous medals.

One will immediately be struck by his quiet and unassuming personality, especially his spirit, undaunted after 90 years of life, and very well complimented by his lovely wife. It is an honor and privilege to be able to meet and talk with one of these amazing men in person, otherwise known only through books or films.

His father, an Issei, came to the US in 1899 and lived in a number of locations, working at various jobs, including as a hotel manager in Tacoma, Washington. He brought over his lovely bride from Japan and settled in Oregon. There they raised their family of eight children. He started a dairy farm and then a plant nursery -- a business that would last three generations to this very day, making it one of the oldest single-family agricultural businesses on the West Coast.

Through those pre-war years they had relatively no problems with the anti-Japanese sentiments that were prevalent in California. At the start of WWII, they voluntarily evacuated to a town in eastern Oregon. There they worked on a farm during the entire war.

My good friend, however, had joined the Army in January 1942. Due to the fact he was of Japanese ancestry, he was kept in office work with the Army until his status changed and he was sent to training camps. He and other fellow soldiers shipped out of Ft. McClellan, Tennessee, on August 24, 1944, as replacements for those special Nisei soldiers of the 442nd, arriving in the Mediterranean theater of operations on September 7.

Joining the nearly 3,000 other Nisei of the 442nd in Italy, he soon became a part of some of the fiercest fighting in Europe, including the renowned break-through to reach the trapped and isolated "Lost Battalion" in the Vosges Mountains in northeastern France. That heroic battle earned the 442nd five Presidential Unit Citations.

Though neither he himself, nor anyone in his family, for that matter, was ever in a relocation center, he still had to deal with the prejudice against Japanese-Americans. Yet he never complained nor did he lash out against those who despised and looked down at him.

After being honorably discharged from the US Army with several medals and citations to his name, he went back home to help out in his father's nursery business. In latter years, he would enjoy taking his daily walks through the greenhouses to check up on "his plants."

Ike passed away on Jan. 18, 2013. A quiet man with an amazing history... he will certainly be missed by many.

As President Truman remarked in July of 1946, these men not only fought the enemy, but they fought against prejudice... and they won.

For comments within the following documents regarding the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, see TL32, TL34, TL42 (very good), TL43, TL46, TL48, and TL63. For a better understanding of the number of medals and awards received by the 100th and 442nd, see Allen's very well researched critique of the Smithsonian Institution's exhibit, "A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans and the U.S. Constitution." See also Hopwood's critique on Medal of Honor awards.

| For the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the

war had been doubly hard. Its men had not only fought the Germans at

their defensive best up the spine of Italy and in the Vosges; they had

also fought prejudice at home. Yet the Niseis' record was unexcelled. In 240 combat days, the original 3,000 men and 6,000 replacements collected eight unit citations, one Medal of Honor, 3.600 Purple Hearts and a thousand other decorations. They lived up to their motto, "Go for Broke": no less than 650 of the Purple Hearts had to be sent to next of kin (many of them in relocation centers) because the soldiers were dead. The 442nd also set an unbeatable mark for soldierly behavior; no man in the outfit had ever deserted. -- TIME, July 22, 1946

|

It has been said that the most-written-about subject of World War II is the evacuation and relocation of the ethnic Japanese (Nikkei) in the United States. There are thousands of books, articles, films, assorted papers, and webpages on the subject, with many more coming out yearly. It is often popularly, though incorrectly, termed as "Japanese-American internment" or the "forcible internment" of "resident Japanese aliens and their children" who were shipped off to "concentration camps."

The whole program was a first for our nation -- how to deal with a large number of people living in the land who had suddenly become "alien enemies." This included not only the Japanese Issei (1st generation), but Germans, Italians, Hungarians, Romanians and other Europeans. They had to be dealt with according to war policy, by apprehension, by deportation, or by placement in internment camps. The problem for the Issei was they had children... and those children were American citizens.

During my initial research into this immense subject, I was bothered by something I had come across before -- the fact that there was a paucity of discussion by the Japanese-Americans about declassified government documents dealing with the reality of what occurred during the war years. I found this same sort of historical blank in Japan while I was searching for anything dealing with the POW camps that were in Fukuoka. (NOTE: The Densho website has an immense collection of primary sources, testimonials and photographs, with more being added weekly.)

A great number of books and websites on this topic portray the United States Government, especially the military leaders, as racist masterminds behind the evacuation to relocation centers, or as some have put it, incarceration in concentration camps. The U.S. has been accused of being white-supremacist, discriminatory, and prejudiced against the Issei and Nisei (2nd generation) who lived in the United States during WWII.

Though my objective is neither to prove nor disprove the legitimacy of the evacuation of the Japanese to relocation centers, I do hope to show a glimpse into the immense preparation and actual undertaking of the task of the program in its several stages, the many organizations involved, and the great care shown to over 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry -- a people who were housed, fed and cared for through the efforts and funds provided by the United States Government, making not simply relocation centers, but entire cities in the wilderness -- a preserved people.

As with any event in the past, unless we were there to experience it ourselves, we must rely on those who experienced and wrote about that event. Even then, we are at the mercy of their powers of recollection and interpretation of what took place. Ultimately this is all we have to go on -- their view of what happened based on their knowledge and interpretation of events at the time. The enormity of this subject, however, is overwhelming. One could never read all there is on the subject nor interview all who were involved.

I would like, however, in order to get as close to the root of these events, to offer a small number of primary source materials that may not readily be available in text format on the Internet, and hence, easily accessible by its search engines. Much of this material has been on the Internet in image format for some time, and therefore I present nothing essentially never-before-seen. As was my method with my website on POW camps in Japan in presenting primary source material, I have transcribed documents from the National Archives for this website in order that viewers may read for themselves verbatim the originals, grasp the full context, and thereby make their own conclusions. This will, I hope, help clear some of the misinformation resulting in shallow assumptions and conjecture on this grand and multi-faceted subject.

Additionally, and related to my initial niche in historical research, I would like the reader to better understand the differences between how Japan treated American prisoners of war and civilian internees in Japan, and how the United States treated civilians of Japanese ancestry during WWII. My first website deals with the former; this site here, with the latter.

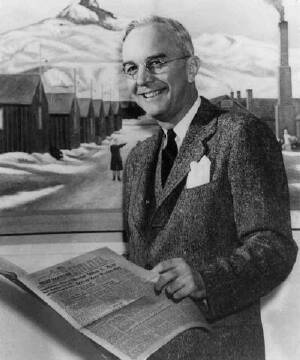

I have predominantly centered on the writings of Dillon S. Myer, who served as National Director of the War Relocation Authority, and hence most knowledgeable, being WRA's Director for almost the entire period this civilian organization was in existence. (Read Facts About the War Relocation Authority for some quick basic information on the WRA.) Due to his position, Myer was able to view a greater spectrum of the many issues facing his staff and the evacuees, and deal as fairly as he could with the US as well as Japanese governments, military as well as civilian personnel. He could also effectively gauge how the public was viewing and reacting to the whole program. His writings show a man of discernment, of concern for human feelings, giving both praise and rebuke where it was due. He was not afraid to stand up for what he believed in, enduring intense pressures and worries from within and without. Please take special note of his speeches, particularly the last of which is included on this website (TL63; TL48 is also very good).

It was one of Myer's unique strengths to be able to succinctly state the marrow of issues, and how to step-by-step solve the problems the Authority faced in a most practical manner. His experience at WRA gave him unparalleled insight into the lives of the Issei, Nisei, and Kibei (Nisei educated in Japan), and his writings reveal the deep understanding, respect and compassion he had for those he was in charge of at the ten relocation centers. (PHOTO: "Dillon S. Myer, Director of the War Relocation Authority, at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center. Center buildings and Heart Mountain in the background." From "An Autobiography of Dillon S. Myer," 1970. Courtesy of the University of California, Bancroft Library at Berkeley, Regional Oral History Office.)

Myer often remarked that the whole topic was extremely complex -- "It is one of the most complex situations that has ever been dealt with." Indeed it was, and indeed it still is, as anyone who has read the numerous varied accounts, first-person and otherwise. One can read an account and come away feeling very anti-American; read another and you feel very anti-Japanese. There is no simple cut-and-dry conclusion that would explain this period of American history.

It is sad, nevertheless, to see attacks on Myer by those who really had no way of knowing Myer's heart and mind, having never met and personally talked with the man nor even read all his writings. It's difficult to determine exactly the agenda of those who smear or attempt to detract from what Myer, or the WRA, for that matter, has done. One clue, however, may be found in remarks on Myer's faith -- that he came from a "puritannical" background, being raised in a strict Methodist family, and holding to the religious tenets he was taught as a youth. It is also very conceivable that the "race-baiters" Myer spoke of so often were not at all pleased with his strong stand against them, Myer having exposed them by name in numerous public speeches. He was not afraid of mentioning just who the "enemies" of the Nikkei were (TL48).

One of the most important of addresses given by Myer was entitled "Problems of Evacuee Resettlement in California." Herein you will see the real heart of Myer towards the people over which he was given directorship, the insight he had regarding these people, and a vision of what would occur if racial prejudice, discrimination and hatred were to break out against other sects or ethnic groups. Of special note are his many comments regarding the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (see above), the formation of which could have very well been due to Myer's efforts; the selective service being reinstated; the whole leave program for work, schooling, etc.; all of which could very well be attributed to his urging. (Be sure to read this Oral History Interview with Dillon S. Myer at the Truman Library website.)

It is important to keep in mind the whole purpose of the relocation program -- to provide temporary housing to evacuees, or as Myer stated succinctly, "the relocation centers were simply temporary homes for people to live in until an orderly process of relocation could be developed." And that orderly process was indeed developed and carried out to completion. It is my hope the following selections from the writings of Dillon Myer will help to settle once and for all the myths, mysteries and misinformed conclusions about most every facet of the evacuation and relocation program.

Another objective I would like to obtain through these pages is to show how life for the evacuees did not consist entirely of suffering, deprivation and disillusionment that is so often the underlying theme in material on this topic. I trust the reader may see in another light the many things that are taken for granted, that the themes of "incarceration" and "racism" will unfold more fully, and that the entire period of the Nikkei in the United States be seen with less ambiguity and assumption.

The record of the past is an ongoing process in the present -- history is being re-interpreted and rewritten as more information is revealed. I have, therefore, attempted to steer clear of speculation and center on the very data that was issued during those war years. To reiterate, what I present here is simply a textualization of already-available archival images in order to make this history more accessible over the Internet as textual media, or more specifically, search-engine friendly. It is my desire that these efforts will be of help to many students of American and Japanese history by providing them a much clearer view of the intricacies of those times, those few seconds on the clock of history.

| I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of War... to prescribe military areas... from which any or all persons may be excluded... [and] to provide for residents of any such area who are excluded therefrom, such transportation, food, shelter, and other accommodations as may be necessary... including the furnishing of medical aid, hospitalization, food, clothing, transportation, use of land, shelter, and other supplies, equipment, utilities, facilities, and services. |

SOURCES

The majority of the documents I have transcribed on the War Relocation Authority and Dillon Myer are found at the Truman Presidential Museum and Library. These filenames are prefixed with "TL."

The majority of documents produced by intelligence agencies are from the Internment Archives (filenames prefixed with "IA"). The photographs are predominantly from University of Nebraska Press. The WRA publications (PDF files) are from the Ohio GODORT Digital Collections and have been collected here for the purpose of future transcription. I welcome any and all volunteer help in transcribing these and other documents.

The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley has a huge image and text database, with excellent search capability, via the Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives, a great site for a quick look at thousands of very interesting photos from the Univ. of California's calisphere. I am most grateful to all of these websites for making these archival images available for perusal via the World Wide Web.

The following are Record Groups at the National Archives which contain much material on this entire subject:

- RG 210 - Records of the War Relocation Authority (includes searchable records on 109,384 individuals)

- RG 60 - WWII Alien Enemy Detention and Internment Case Files; Compensation and Redress Case Files (26,550 claims for compensation and 82,219 restitution payment claims)

- RG 220 - Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) Records (20 days of hearings and testimonies from more than 750 witnesses between July and December, 1981)

- RG 389 - Office of the Provost Marshal General (OPMG) Records (individuals' release from relocation centers, information about Japanese-American men eligible for military service, personal data cards, etc.)

- RG 499 - Western Defense Command (WDC) Records (assembly center records, with folders on individual families).

TRANSCRIPTION NOTES

In order to enable the reader to grasp the main points of the following documents which may otherwise be overlooked, I have taken the liberty to put in bold type sentences and phrases which help the reader catch the main points in the pages.

Any additions I have made to the text are enclosed in [brackets]. Spelling errors may have been either inadvertently overlooked or left on purpose.

The Chronology of Events used in the Table of Contents is from Dillon Myer's Uprooted Americans.

All photos within the various documents have been added to complement the text and are not a part of the originals. Readers may save the images and later view the embedded source notes for each image with an image utility (e.g. VuePrint, "N" function).

In some of the intelligence documents, portions have been blacked out through redaction in the originals by the various intelligence agencies. These portions are marked by XXXXX.

Continue to Table of Contents >

| While some of the evacuees will never

recover from the bitter experiences of the evacuation, the Authority is

convinced that because of the industry and integrity of the Japanese

Americans, they will quickly build for themselves a better social and

economic pattern than they had before the war. -- from The Relocation Program, 1946

|