Union Calendar No. 243

78TH CONGRESS 1st Session

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

REPORT No. 717

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

REPORT No. 717

REPORT AND MINORITY VIEWS OF

THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES ON JAPANESE WAR RELOCATION CENTERS

THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES ON JAPANESE WAR RELOCATION CENTERS

SEPTEMBER 30, 1943. -- Committed to the

Committee of the Whole House on the state of the Union and ordered to

be printed.

MR. COSTELLO, from the Special Committee on Un-American Activities, submitted the following

REPORT

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE WAR RELOCATION CENTERS

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, considerable fear was rife among the residents on the west coast of the United States, where approximately 120,000 citizens of Japanese ancestry and Japanese nationals had concentrated. Because of this situation and particularly for military reasons, General DeWitt, commanding general of the Western Defense Command, early in 1942 ordered the evacuation of persons of Japanese ancestry, United States citizens and aliens alike, from certain areas of the west coast.

The evacuation was first put on a voluntary basis and some 8,000 persons of Japanese ancestry removed themselves into the interior of the United States. However, this procedure proved to be ineffective and as a consequence on March 29, 1942, the voluntary evacuation was abandoned and a freezing order was issued by the commanding general of the Western Defense Command, which in effect held all persons of Japanese ancestry within the affected zones until some orderly procedure could be drawn up which would bring about the complete removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry from the military area of the west coast.

Meanwhile the War Relocation Authority was established on March 18, 1942, by Executive Order No. 9102, to carry out the evacuation and to care for the evacuees. This agency proceeded to construct 10 relocation centers in the following places: Colorado River relocation center, Poston, Ariz.; Gila River relocation center, Rivers, Ariz.; Manzanar relocation center, Manzanar, Calif.; Tule Lake relocation center, Newell, Calif.; Minidoka relocation center, Hunt, Idaho; Central Utah relocation center, Topaz, Utah; Heart Mountain relocation center, Heart Mountain, Wyo.; Granada relocation center, Amache, Colo.; Rohwer relocation center, Rohwer, Ark.; Jerome relocation center, Denson, Ark.

Following the issuance of the freezing order, all Japanese were removed to temporary assembly centers and from there were sent to the various relocation centers. The removal to the Relocation Centers began in May of 1942. Approximately 106,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were evacuated to the various centers.

THE COMMITTEE'S INVESTIGATION

From the second year of its work (1939) down to the present time, the Special Committee on Un-American Activities has carried on a continuous investigation of subversive and un-American activities among the Japanese who are resident in the United States.

Previous committee reports have dealt with many phases of the question of Japanese subversive activities. At the end of 1940 the committee issued a special report dealing with totalitarian propaganda in the United States which revealed that many tons of Axis propaganda were being unloaded from Japanese steamships docking at ports on the west coast of the United States. This report led to immediate action by the Post Office Department which ordered that all such propaganda material be seized on its arrival in this country. Early in 1942 the committee issued a special report [related ONI report here] which showed that numerous Japanese organizations operating in this country were fronts for the Japanese Government and that numerous members of these organizations were engaged in espionage for the Tokyo Government.

The present report reflects the current stage of the committee's continuing work on the question of the subversive and anti-American activities of Japanese who are resident in the United States. The report deals primarily with Japanese subversive activities within the war relocation centers and with the possible release of dangerous Japanese agents of espionage from these centers.

During the latter part of 1942 and the first half of the present year, the committee received numerous complaints from citizens and organizations on the west coast and in Western States concerning the handling and release of the Japanese by the War Relocation Authority. The committee also received requests from Members of Congress and from State authorities of the affected areas to make an investigation of the relocation centers.

Early in May 1943 a member of this committee, Hon. J. Parnell Thomas of New Jersey, went to Los Angeles, Calif., and conferred with State authorities, various citizens, and groups, and reported back to the committee that he felt the Japanese situation and the administration of the War Relocation Authority needed an immediate and thorough investigation. He called upon the President to halt the then existing policy of the War Relocation Authority which called for the release of approximately 1,000 evacuees per week for resettlement throughout the country.

Pursuant to the recommendation of Congressman Thomas and at the request of Congressman Costello, a member of this committee, and a Representative in the House from the Los Angeles district, which is vitally affected by the Japanese problem, the committee ordered an investigation of the various relocation centers and detailed investigators to go to the centers and conduct an investigation.

The charges which appeared in the numerous complaints received by the committee and which were reflected in the preliminary investigations of the committee's agents were as follows:

1. That Japanese were being released at the rate of 1,000 a week and that it was very possible that among those released were some whose allegiance had been pledged to the Japanese Government.

2. That there were thousands of Japanese in the relocation centers who had openly expressed their loyalty to Japan and had requested repatriation.

3. That 24 percent of the evacuees of draft age (17 to 38 years of age) had stated on the questionnaire circulated among them by the Army that they were not loyal to the United States but held their sole allegiance to the Emperor of Japan.

4. That the loyal and disloyal Japanese were intermingled without any semblance of segregation, and were receiving the same treatment in the way of accommodations, food, etc.

5. That the Japanese evacuees were being supplied food through the Quartermaster Corps of the Army in greater variety and quantity than was available to the average American consumer.

6. That the discipline in the various relocation centers was very lax, and that considerable Government property had been destroyed by some of the Japanese.

The foregoing charges, which were embodied in complaints received by the committee and which grew out of preliminary investigations, were made the basis for a more thorough and formal investigation. On June 3, 1943, the chairman of the Special Committee on Un-American Activities appointed a subcommittee to conduct an investigation into these charges and make a report of its findings. The subcommittee was composed of John M. Costello, of California, chairman, Herman P. Eberharter, of Pennsylvania, and Karl E. Mundt, of South Dakota.

The subcommittee left almost immediately for California. From June 8 to June 17 the subcommittee held hearings in Los Angeles where it took more than 1,000 pages of testimony, principally from men who were then or had been recently on the administrative staffs of the relocation centers. On June 18 the subcommittee held hearings in Parker, Ariz., near the Poston Relocation Center. From July 1 to July 9 the subcommittee held its hearings in Washington, D. C., at which the principal witness was Dillon S. Myer, Director of the War Relocation Authority. Also among the witnesses in Washington were former officials of the Japanese American Citizens League whose Washington files the committee had obtained by subpena on June 11, 1943. The committee also heard in executive session representatives of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Department of Justice, and the War Department.

ADMINISTRATIVE ASPECTS OF THE WAR

RELOCATION AUTHORITY

This committee does not consider it necessary to discuss in detail the administrative errors and deficiencies of the War Relocation Authority, which were indicated by voluminous evidence received in the course of the subcommittee's hearings. The Director of the War Relocation Authority, Dillon S. Myer, was frank in admitting that many mistakes had been made. Only those administrative errors which bear directly or indirectly upon the subject of subversive and un-American activities come within the special interest of this committee.

The fitness of much of the personnel of the War Relocation Authority for its highly specialized task has been opened to serious question by the evidence which the committee has received. The committee is convinced that this manifest unfitness may account in large part, or even entirely, for the errors of the administration which involve the subject of subversive and un-American activities.

LACK OF JAPANESE EXPERTS IN WAR RELOCATION

AUTHORITY

Out of an administrative personnel of the War Relocation Authority which numbers approximately 2,500 persons, an absolutely negligible percentage seems to have been qualified for their positions by any knowledge, even elementary, of the language, culture, and ways of the Japanese. The Director of the War Relocation Authority himself appears to be typical of this total neglect to enlist an administrative personnel which possessed any degree of expertness or experience which would qualify them to handle 100,000 persons of Japanese ancestry. Mr. Myer had a record of 28 years as an expert in agriculture when he was called upon to administer the delicate, admittedly onerous, and largest mass resettlement program ever carried out by any government. It is apparent from the testimony given before the subcommittee that few, if any, among the administrative personnel of the War Relocation Authority had ever so much as read a book on the Japanese before they undertook their heavy responsibilities for dealing with this racial group. Certainly there exists within the War Relocation Authority a complete lack of familiarity with the subversive Japanese organizations or even with the general techniques of subversion.

SEGREGATION

When Mr. Myer was before the subcommittee, he stated that a program of segregating the disloyal from the loyal Japanese was to be inaugurated at an early date. While the committee heartily approves the announcement and earnestly hopes that it will be given speedy effect, it is impossible for us to excuse the delay in adopting a policy of segregation. The committee further notes that the War Relocation Authority's announcement of a segregation policy came after the United States Senate adopted a resolution requiring such segregation, and after the subcommittee of this committee had held public hearings which revealed the urgent need for segregation.

The committee is forced to conclude, on the basis of all the evidence before it, that the War Relocation Authority has been extremely dilatory in the matter of segregating the disloyal elements in the centers from those who are loyal Nisei or law-abiding Issei.

MR. EMPIE ON SEGREGATION

On June 9, 1943, in Los Angeles, the subcommittee heard the testimony of Augustus W. Empie, chief administrative officer, Colorado River War relocation project (Poston), near Parker, Ariz. Mr. Empie is in charge of personnel, communications division, supply and transportation division, procurement division, fiscal division, mails and files divisions, and has general supervision over the chief steward's office.

Mr. Empie's testimony brought out the fact that is was his opinion that much of the trouble at Poston could be attributed to the failure to segregate the loyal from the disloyal Japanese, and he was questioned specifically in this regard.

MR. MUNDT. That was the next thing I was going to ask you about. I was going to ask you if you didn't feel that the fact you haven't segregated the bad fellows from the good ones has had a bad effect on the Japanese who might be inclined to work?

MR. EMPIE. Absolutely. I think that is the first and foremost problem the War Relocation Authority should have attacked and solved immediately -- they should have arranged immediately to get these people out.

GANGS AT MANZANAR

As an example, the need for segregation was long ago strikingly evident as a result of the operation of criminal and subversive gangs in the relocation center at Manzanar (Calif.).

Tokutaro Slocum, one of the few Japanese ever to be made a citizen of the United States by an act of Congress, was called as a witness before our subcommittee. Slocum was one of the evacuees who lived at Manzanar. When asked if he had gained any information concerning "organized groups of a secret character working in Camp Manzanar," Slocum replied:

Well, sir, I was a special investigator there, or inspector there, so it was my duty to obtain all this information and report that to the duly constituted authorities, so I happened to come across most of them, and many of them I would say were Blood Brothers, Black Dragon, the Dunbar Corps, or Dunbar Gang, and the San Pedro Yogores.Slocum then testified concerning the methods of intimidation and terrorization which were employed by these gangs at Manzanar.

Slocum's testimony was completely substantiated by confidential reports which the subcommittee obtained by subpena. The following are excerpts from those reports:

Now, with more leisure time, dormant forces are beginning to create disturbances. What has seemingly appeared to most Caucasian administrators as a placid community life in reality covered a cauldron in which differing ideologies, immiscible as oil and water, seethed and boiled. Surface indications of this internal strife have appeared from time to time. However, center officials have usually dismissed these symptoms with an academic leniency.

The real threat to peace and order within the centers will not come from individual lawlessness. The bombshell that will shatter these communities will be the blow-off of (1) accumulated resentments, (2) harbored injustices, (3) racial discriminations, (4) pro-Japan convictions, and (5) real and fancied grievances. As time goes on, rather than a settling process, mob outbreaks, mass demonstrations, gang atrocities, and acts of terrorism will recur frequently.

War Relocation Authority administrators must realize the dynamite they are dealing with; they must be realistic; they must not encourage the mushrooming of small incidents by condoning with official laxity; individuals advocating constructive attitudes and activities must be shielded from vengeful harm; deleterious elements in each camp must be recognized and intelligent yet stern methods must be instituted to curb them.

* * * * * * *

Numerically this pro-Japan element is small, but the damage their insidious propaganda can do to the peace and order of the community should not be too lightly regarded.

* * * * * * *

Internal security should be exactly what its title connotes. Reports issuing from some centers indicate that security of life and limb for those bespeaking constructive attitudes does not exist. On the other hand, malefactors have been so condoned that their nefarious beatings of decent citizens continues not only unabated but with increasing frequency.

* * * * * * *

Manzanar gangdom is usually identified by the people as one of three groups: (1) Terminal Islanders, known also as Yogores, or the San Pedro Gang, (2) the Dunbar Gang, (3) The Blood Brothers Corps, known also as Yuho Kesshidan.

* * * * * * *

THE BLOOD BROTHERS CORPS

This appears to be an underground movement political in nature. Unlike the San Pedro Gang or the Dunbar Gang, no member of this group has come out into the open and acknowledged himself as a Blood Brother.

* * * * * * *

On Friday and Saturday, November 6 and 7, the members of the Manzanar commission on self-government received letters via mail from the Blood Brothers. The following 17 persons, comprising the commission, were recipients: Frank Chuman, Dr. James M. Goto, Jack Iwata, Rev. J. A. Kashitani, Mrs. Niya Kikuchi, Choyoi Kondo, Joe Masaoka, Miss Chiye Mori, Rev. Shingo Nagatomi, Frederick Ogura, Togo Tanaka, Walter Watanabe, Frank Yasuda, Sho Onodera, Rev. Tashimi, Kiyoshi Higashi, Tom Imai.

There were two sets of letters, both in Japanese, apparently written by two different persons.

Following is a literal translation of the shorter of the two letters:

"Think of the shame the American Government has put us into. Think of the disruption of properties and the imprisonment of the Nisei.

"To start a self-government system now is nothing but a dirty selfish scheme. As the Army put us in here without regard to our own will, we should leave everything up to the Army, whether they want to kill us or eat us.

"Because this is the only way the American Government can think of as a means of absolving itself from the blame of mis-conducting its affairs, the Government thought of a bad scheme, that is, this formation of self-government system.

"The hairy beasts (white) are out to actually run the Government, while using you people who can be used. It is evident if you read article I of the charter, and can be proved by the facts of the past. You fellows who are acting blindly are big fools.

"If you do such things as those, which tighten the noose around the necks of your fellow people, some day you will receive punishment from Heaven so beware.

"BLOOD BROTHERS CORPS WHICH

WORRY FOR THEIR FELLOW PEOPLE."

* * * * * * *

Following is a translation of the longer of the two letters: (Both translations by Akira Dave Itami of the Information Office.)

"Calling you fools who are running around trying to set up a self-government system.

"Think back. The fact that the positions, the properties, and the honor which our fellow Japanese built up and won by blood and sweat during the past 50 years have all been stamped and sacrificed by the arrogant and insulting American Government after we have been put into this isolated spot.

"For what are you beating around? What use is there for establishing self-government? Especially with such a charter so full of contradictions? Although we are ignorant people, we can foresee the tragic results which will come out of this self-government.

"Remember that the majority of our people are absolutely against the self-government system. What do you think of the fact that 6 months ago, in Santa Anita, the same attempt which you are now trying, was made, to organize a self-government, but it broke down before it materialized.

"Leave everything completely as the Army pleases. If you nincompoops realize the fact that you are Japanese, why don't you assume the honorable attitude which is typical of Japanese? What a shameful sight you are about to present by being fooled by the sweet words of the Government. By so doing, you are inviting suffering to your fellow Japanese.

"We fellow Japanese are all like fish laid on the cutting board, about to be sliced. To jump around at this stage is a cowardly thing to do. Better lay down and let the Government do as it pleases, either cook us or fry us.

"You should remain calm and conduct yourselves like nationals of a first-class power. Give more thoughts and deep reflections as to your attitude.

"BLOOD BROTHERS CORPS WHICH IS

CONCERNED OVER FELLOW NATIONALS"

* * * * * * *

The great need for a determined policy of segregation was amply indicated by the answers to the loyalty question contained in the Army questionnaire which was filled out by the Japanese in the relocation centers in February of the present year. An alarming proportion of Japanese American citizens of draft age (17 to 38), frankly refused to declare their loyalty to the United States.

The loyalty question read as follows:

Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic foes and forswear any form of allegiance to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?The following tabulation presents in the most simplified form possible the extent to which the Japanese-American citizens of draft age declared their loyalty to the United States:

| Relocation center |

Number registered |

Number answering "No" to

loyalty question |

Number volunteers |

| Central Utah |

2,420 |

805 |

116 |

| Colorado River |

3,358 |

671 |

238 |

| Gila River |

2,488 |

547 |

119 |

| Granada |

1,117 |

107 |

121 |

| Heart Mountain |

1,881 |

451 |

47 |

| Jerome |

1,341 |

116 |

33 |

| Manzanar |

1,826 |

913 |

101 |

| Minidoka |

1,607 |

32 |

310 |

| Rohwer |

1,585 |

306 |

37 |

| Tule Lake |

2,342 |

835 |

59 |

| Total |

19,963 |

4,763 |

1,181 |

| Average, percent |

----- |

24 |

6 |

The committee reiterates its conclusion that there was an alarming proportion of the Japanese-American citizens of draft age to avow their unqualified loyalty to this country. From the foregoing tabulation, it is apparent that avowed disloyalty reached the high percentage of 24.

A more complete break-down of the answers to the loyalty question is given in the following tabulation:

| Relocation center | Total eligible to reg- ister |

Total regis- tered |

Total ac- count- ed for |

Yes |

Non- affirm- ative an- swers |

No reply |

Yes (per- cent) |

Non-af- firm- ative an- wers (per- cent) |

No reply (per- cent) |

| Central Utah: |

|||||||||

| Hawaii |

163 | 163 | 163 | 25 |

133 |

0 |

15.3 |

84.7 |

0 |

| United States |

1,447 | 1,447 | 1,447 | 1,015 | 462 |

0 |

65.7 |

31.3 |

0 |

| Colorado River |

3,405 | 3,405 | 3,211 | 2,601 | 596 |

14 |

81.0 |

18.6 |

.4 |

| Gila River |

2,630 | 2,588 |

2,502 | 1,599 | 901 |

2 |

63.9 |

36.0 |

.1 |

| Granada |

1,342 | 1,342 | 1,254 | 1,222 | 27 |

5 |

97.4 |

2.2 |

.4 |

| Heart Mountain |

1,964 | 1,963 |

1,963 | 1,809 | 253 |

101 |

82.0 |

12.9 |

5.1 |

| Jerome |

1,592 | 1,591 | 1,385 | 895 |

417 |

73 |

64.6 |

30.1 |

5.3 |

| Manzanar |

1,989 | 1,989 | 1,885 | 921 |

950 |

4 |

48.9 |

50.9 |

.2 |

| Mindidoka |

1,629 | 1,603 | 1,680 | 1,497 | 61 |

22 |

94.7 |

3.9 |

1.4 |

| Rhower |

1,608 | 1,608 | 1,410 | 1,150 | 252 |

8 |

81.5 |

17.9 |

.6 |

| Tule Lake |

2,960 |

2,330 | 2,274 | 1,489 | 783 |

2 |

65.5 |

34.4 |

.1 |

| Total |

20,679 |

19,979 |

19,164 | 14,023 |

4,850 |

231 |

73.4 |

25.4 |

1.2 |

The foregoing tabulation indicates that disloyalty among those of draft age at the Manzanar center was in excess of 50 percent. The committee is of the opinion that such a result obtained from the questionnaire called for immediate separation of the disloyal from the loyal, and is at a loss to understand the reasoning of the War Relocation Authority which prompted its inaction in so important a matter.

PRESERVATION AND PROMOTION OF JAPANESE

CULTURAL TIES

Indicative of the same type of negligence which caused the War Relocation Authority to fail to adopt prompt and drastic measure of segregation in the centers, was the Authority's callous promotion of cultural ties with Japan.

Mr. Myer admitted in his testimony before the subcommittee that at one time the War Relocation Authority was paying at least 90 instructors in Judo at a single center. Judo is a distinctively Japanese cultural phenomenon. It is more than an athletic exercise. By the employment of 90 instructors at one center, the Authority was obviously promoting Judo among Japanese-Americans who did not already know it. Various other forms of so-called recreation which could only have the effect of a tie-back to Japan were likewise promoted in the centers and their promotion was paid for out of the War Relocation Authority's funds which come ultimately from the taxpayers of this country. The same is true of instruction in the Japanese language. It is one thing for the Government to give instruction in the Japanese language to those who the Government has reason to believe will shortly utilize that instruction in some intelligence agency. It is a totally different thing to post notices on the bulletin boards of the centers that one and all may enroll in courses in the Japanese language. American citizens are citizens regardless of their ancestry, and there is no possible justification whatever for a program which goes out of its way to stimulate the interest of an American citizen in the culture of a foreign country from which that citizen has presumably been completely separated by the very fact of his American citizenship.

Every fact adduced in evidence before the subcommittee indicated that the War Relocation Authority had before it an almost unparalleled opportunity to inaugurate a vigorous educational program for positive Americanism. At the same time, the committee is unable to arrive at any other conclusion than that the Authority treated this opportunity with the utmost reprehensible indifference. And not only that, but the Authority proceeded to make outlays of funds for the express purpose of forcibly reminding the residents of the centers that they stemmed from Japan, whereas the loyal at least should have been encouraged by every possible means to regard themselves as Americans and Americans only.

NORTH AMERICAN MILITARY VIRTUE SOCIETY

(BUTOKU-KAI)

This committee has made an exhaustive study of the Japanese organization known as the Butoku-kai. It must assume that the War Relocation Authority has done the same or has at least availed itself of the information on the Butoku-kai in the files of the intelligence agencies. Among other highly important items of evidence bearing upon the organization, the committee has obtained the names of several thousand members of the Butoku-kai from its own records.

There is no doubt whatever in the minds of any competent authorities, including all of the intelligence agencies of the United States Government, that the Butoku-kai is a subversive organization. The representative of the joint Japanese-American board who testified before the subcommittee stated that his board so regarded the Butoku-kai and that any Japanese evacuee in the relocation centers who was a member of the organization should be considered ineligible for release from the centers. This committee concurs completely in that view.

While it is overwhelmingly evident that the Butoku-kai is of a subversive character, it is extremely doubtful that the War Relocation Authority so considers it. This conclusion is borne out by the fact that the War Relocation Authority has approved the release of evacuees who have been members of the Butoku-kai.

The subcommittee submitted a list of the names of some of the members of the Butoku-kai to the Director of the War Relocation Authority with the request that he make a check to ascertain whether or not any of them had been released from the centers. Out of a possible 215 names which the War Relocation Authority was able to identify, 23 have been released by the Authority.

The committee does not allege that all of these 23 members of the Butoku-kai will proceed to use their freedom to commit acts of sabotage or espionage. The committee does hold, however, that the release of these 23 Japanese is evidence of the incompetence of the War Relocation Authority to exercise proper safeguards both for the national security and for the thousands of loyal Japanese as well.

The committee offers a brief summary of the evidence of the subversive character of the Butoku-kai to substantiate its conclusion that the War Relocation Authority has been negligent or incompetent in the performance of its duties.

The Butoku-kai has approximately 60 branches in the United States prior to Pearl Harbor. About 50 of these were in the State of California. Approximately 10,000 Nisei (American citizens of Japanese ancestry) were members of the Butoku-kai in this country.

The investigations of the Special Committee on Un-American Activities have established the following additional facts concerning the Butoku-kai:

1. Butoku-kai was the youth section of the Black Dragon Society of Japan.

2. Mitsuru Toyama, head of the Black Dragon Society in Japan, was adviser to the Butoku-kai in the United States.

3. The declared purpose of the Butoku-kai in this country was "To enhance the spirit of Japanese military virtue, to guide the citizens of Japanese ancestry, and to encourage physical culture."

4. The instructors who were engaged to teach the military arts to the Nisei in the United States under the banner of the Butoku-kai came to this country from Japan, and were principally Japanese Army and Navy men. However, local priests of both the Shinto and the Buddhist cults acted as instructors.

5. Butoku-kai was imported into the United States by one Tekichi Nakamura, who arrived here from Hawaii on September 27, 1929. Nakamura came to the United States in the guise of a Korean, but later dropped that pretense. Nakamura began immediately to enroll Nisei in his organization and to give them instruction in swordsmanship.

6. In his youth, Nakamura operated as a bandit in Manchuria.

7. Immediately prior to his coming to the United States, Nakamura was received at the Yokosuka naval base by Kurozaki of the Japanese Navy who gave him the following commission:

Here comes the very messenger I desire. In the course of my military duties I have often been to America and have had familiar chats with our brethren on the coast there. Though they know something about the joys and sorrows of parents and guardians, I learned by discussion of all their joys and sorrows, the problem filling their hearts was about the rearing of second generation (Nisei) * * * So, if you are going to America, how are you going to instruct and nourish the young people of Japanese lineage there? Put your mind on this problem first of all -- and open out some good way for us.8. On a return visit to Japan in 1931, Nakamura gained as patrons for his work in the United States General Suzuki, General Araki, and Admiral Kato. He returned to the United States in July 1931.

9. Shortly afterward, Nakamura -- this teacher and leader of 10,000 Nisei in the United States -- went once more to Japan, taking with him a party of 14. He and his party were received by Government officials at Yokohama and then proceeded to Tokyo where they worshiped at the imperial palace.

10. In 1933 Nakamura again went to Japan, taking with him a party of 14 Nisei. They again worshiped at the imperial palace in Tokyo and were received by all the Cabinet Ministers and by Admiral Togo. One of the members of Nakamura's party made a speech at a great public reception in which she (a Nisei) declared:

We, in whose veins flows the blood of the valiant Japanese people, must throw off the American atmosphere and learn the spirit of Japan's way of the warrior.11. At Kyoto, ancient capital of Japan, Nakamura and his party of Nisei were received by Prince Nashimoto, himself a high official of the Butoku-kai in Japan, who declared to Nakamura: "Go on laboring still more for the sake of our country." The party returned to the United States in September.

12. In 1934, when the Butoku-kai held a national meeting at San Francisco, the Japanese consul general declined an invitation to address the meeting on the ground that he wished to "avoid rousing sleeping dogs."

13. In one of his latest reports, Nakamura boasted the following:

Thus the North American Butoku-kai has prepared firm fundamental organizations. By means of the discipline of swordsmanship, the Nisei have awakened to the Japan spirit.14. When Nakamura sought to reenter the United States after his fourth journey back to Japan, he was detained by the immigration authorities at Angel Island for a period of 4 months and was then admitted after intervention on his behalf by the Tokyo government, Ambassador Saito, and numerous followers in the Butoku-kai.

15. Nakamura raised funds in the United States for the establishment of the North American College of the Imperial Way at Tokyo. The primary purpose of the college was for the instruction of Nisei sent from the United States. The college was formally opened on July 10, 1938.

16. The list of sponsors of the North American College of the Imperial Way included Mitsuru Toyama, head of the Black Dragon Society of Japan, 10 admirals of the Japanese Navy, 21 generals of the Japanese Army, and 82 prominent figures of the Japanese political world. The Special Committee on Un-American Activities has the names of all these sponsors.

17. In 1935, Consul Tomokazu Hori became president of the Los Angeles Butoku-kai. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hori made daily broadcasts from Japan. On his short-wave broadcast of April 23, 1943, Hori gloated over the execution of the American flyers who were captured after the Doolittle raid.

18. The president of the Seattle branch of Butoku-kai wrote the following:

If anything were to bring about the paralysis of our national character which has come down to us from our ancestors, or if we were to lose our Japanese spirit and morale, not only would the state of our country become precarious but it would meet the fate of utter destruction. This is as clear as day. Therefore we Japanese, whether at home or beyond the seas, without distinction, must polish up our Bushido spirit which is our own traditional nature. We should foster this with enterprising energy. At present our Empire is facing a crisis against the proud and unruly sword of China -- for the purpose of creating a hundred years of peace in the Orient.19. At a meeting of the Oregon branch of Butoku-kai in 1937, there was, according to the organization's own report, "silent prayer for the success of the Imperial Army," and at its conclusion "three banzais for the fall of Shanghai."

20. The Butoku-kai's official history of the Seattle branch states that there was a special demonstration in the White River district where a Japanese flag autographed by Mitsuru Toyama was presented to the Sumner branch of Butoku-kai. Toyama, it will be remembered, is the head of the Black Dragon Society of Japan.

21. The leader of the Seattle branch of Butoku-kai wrote as follows:

Your problem, however, is much more intricate because you have as your parents subjects of our Japanese Empire which is struggling for the top rank amongst the great powers of the world. * * *

I pointed out that the causes of Japan's foreign wars were unavoidable on account of the foreign races, but America's wars were based on her own ambition -- so that there was a great deal of difference between them.

BRANCHES OF THE BUTOKU-KAI

The committee was able to locate the locations or names of the following branches of the Butoku-kai:

| Hawaii (Honolulu branch) |

Bakersfield |

Fresno |

| Ono |

Dominguez Hill |

Reedley |

| Watsonville |

Coast League |

Visalia |

| Campbell |

San Joaquin |

Delano |

| Sebastopol |

Northwest League |

Livingston |

| Baggerville |

Main office of Friends of Swordsmanship

Society, Sumner |

San Pedro |

| Loomis |

Concord |

Long Beach |

| Oban |

Monterey |

Norwalk |

| Florin |

Salinas |

Seattle |

| Lodi |

Suisun |

White River |

| Viola |

Sacramento |

Tacoma |

| Farrar |

Marysville |

Portland |

| Dinuba |

Taisho Division |

South Park |

| Hanford |

Stockton |

|

| Lindsay |

Madera |

RELEASE AND RESETTLEMENT PROGRAM OF THE

WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

The steady release since July 1942 of the Japanese from the relocation centers by the War Relocation Authority, to resettle and relocate in various sections of the United States, has given rise to considerable anxiety among the people of certain sections of the Nation. This anxiety has resulted from doubts as to the loyalty of the evacuees who are being released. It is this phase of the War Relocation Authority's program with which the committee is most concerned, for we feel that if this program of mass release is to continue it is imperative that the proper investigative machinery be set up to assure the citizens of this country that every person who is released from a relocation center has been thoroughly investigated and cleared as to loyalty by a competent and qualified board or agency charged directly with that responsibility. The release and resettlement program of the War Relocation Authority, in the opinion of this committee, has been very unsatisfactory, primarily for the reason that no thorough investigation by the proper authorities has been made of those evacuees who have been released, and, furthermore, if the present program of the War Relocation Authority is continued there is little hope that any such investigation will be made in the future.

The War Relocation Authority issues three types of leave:

1. Indefinite leave, which permits evacuees to leave the relocation centers after they have made arrangements for employment outside. There are no limitations placed upon them except to abide by the law and to remain outside of military areas from which they are excluded by military orders.

2. Short-term leave, which permits an evacuee to leave the relocation area for a limited period of time, not to exceed 30 days, to attend to affairs which require his presence or to interview a prospective employer, etc.

3. Seasonal work leave, which permits an evacuee to go to a particular locality to accept seasonal employment, such as work in beet fields, etc.

On July 6, 1943, Mr. Dillon Myer, Director of the War Relocation Authority, testified that as of July 3, 1943, there were 15,305 evacuees on seasonal and indefinite leave, 9,359 of which were out on indefinite leave and the remainder on seasonal leave, working largely in the agriculture fields and irrigated areas of the Midmountain and Western States. Mr. Myer told the committee that the War Relocation Authority was now in the midst of an intensive program of resettlement, and that they had been releasing approximately 500 evacuees a week on seasonal leave and 500 a week on indefinite leave, or a total of approximately 1,000 per week. He testified further that included in the group being released on indefinite leave were Kibei (born in the United States and educated in Japan), Issei (Japanese nationals) and Nisei (American citizens of Japanese ancestry). He stated that 15 percent of those being released for indefinite leave were Issei.

The leave and resettlement program of War Relocation Authority was first inaugurated July 20, 1942, by the issuance of administrative instruction No. 22 which permitted indefinite leave to citizens only. This program remained in effect until October 6, 1942, when the leave regulations were changed to permit citizens and aliens alike to apply for indefinite leave.

During this period, applicants for indefinite leave were subject to only two loyalty checks of investigations: (1) Home check; (2) name check against the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other intelligence agencies' records. In addition, their applications had to be approved by the Washington office of the War Relocation Authority. The home check was conducted by the War Relocation Authority and consisted of communicating with former employers, neighbors, and friends of the subject. In the case of the Federal Bureau of Investigation name check, the name of the subject was submitted to the Bureau which in turn ran the name against its records. This did not include a fingerprint check and the subject was not investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. If this check revealed any information it was transmitted to the War Relocation Authority for its information and guidance and without recommendation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

NO F. B. I. INVESTIGATION

The committee at this point would like to emphasize that at no time has the Federal Bureau of Investigation investigated the evacuees who were released for indefinite leave although this is the general impression throughout the country. This false impression in some measure was brought about by an erroneous statement made by an official of the War Relocation Authority to the effect that all evacuees who were released for indefinite leave had been investigated and cleared by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. This was later denied by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the War Relocation Authority.

On April 2, the War Relocation Authority further liberalized its release program by eliminating the Federal Bureau of Investigation name check and the home check. Under the present program established by supplement 9 of Administrative Instruction No. 22, the project directors of the various relocation centers themselves can make their own determination (with certain limitations) as to the release for indefinite leave of an evacuee. In other words, the only check now in effect by the War Relocation Authority is the investigation made by the project director himself which is largely a questionnaire investigation and it is entirely within his discretion as to who will be released.

When Mr. Myer was before the subcommittee, he stated that all Nisei evacuees who were released would eventually be checked by the Japanese American Joint Board, which is composed of representatives of the Army, Navy, War Relocation Authority, and for a time, a liaison representative from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The subcommittee heard in executive session the officials of this Board and it was determined that the Japanese American Joint Board exercises no jurisdiction or authority over the War Relocation Authority except in the case where an evacuee is released for employment in a vital war plant or where the evacuee is to go into the eastern military area or southern military areas. The Federal Bureau of Investigation withdrew its liaison representative from the Board for the reason that the Board had no authority over the release program of the War Relocation Authority and could not enforce its decisions as to the loyalty or disloyalty of an evacuee upon the War Relocation Authority.

The Japanese American Joint Board was established by the War Department primarily to determine how many of the 38,000 citizen evacuees (Nisei) between the ages of 17 and 38 could be utilized in the Army or in vital war plants or in other employment in which they could assist the general war effort. In conjunction with this program, the Army set up a Japanese combat unit located at Camp Shelby, Miss., which now has an enlistment of approximately 7,000 Japanese American citizen soldiers. This Joint Board set out to determine the loyalty and qualifications of the 38,000 registrants. As previously stated, the committee heard in executive session the officials of this Board and we were very favorably impressed with the thorough job of investigation and classification which they are doing. However, the Board's authority does not extend far enough to permit it to exercise its authority over the entire release program of the War Relocation Authority. Within the next several months, according to the officials of the Board, it will have completed its investigation or screening process of the entire 38,000 evacuees. But during this period, under the present policy of the War Relocation Authority, it is possible that thousands of evacuees will be released without having been screened or investigated by the Joint Board. For this reason it is necessary that a new board with complete authority over the War Relocation Authority's release program be set up immediately or such authority be delegated to the Japanese American Joint Board.

SEASONAL LEAVE

During 1942 there was no check made against evacuees who were released for seasonal leave. However, this was changed late in 1942, and at the present time evacuees released for seasonal leave receive the same check as those who apply for indefinite leave. Mr. Myer told the subcommittee that many of the evacuees who left on seasonal leave found homes and steady employment and, therefore, applied for and obtained indefinite leave without having to return to the relocation center.

The committee is definitely of the opinion that the present release procedures of the War Relocation Authority are entirely too loose and it cannot be too emphatic in its recommendation for the immediate establishment of a competent and qualified board of agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Naval Intelligence, Military Intelligence, War Relocation Authority, and other pertinent agencies which would pass on every application for leave and with full authority to enforce its decisions. By such a procedure the people and the country generally and the communities where the evacuees are relocating would be assured that there was no question concerning the loyalty of these people. It would, therefore, relieve the released evacuees of any stigma of disloyalty and would at the same time bring about a more compatible degree of community acceptance for the evacuees.

AN INDEFENSIBLE RELEASE PROCEDURE

The War Relocation Authority, through its employment and resettlement division, has recently set up a plan to place hundreds of Nisei in civil-service employment of the Federal Government. During the past few weeks hundreds of applications from Nisei evacuees have been submitted to the Civil Service Commission by the War Relocation Authority. As is well known, the Civil Service Commission has always conducted a very thorough investigation of all applicants for Government positions with particular emphasis on the subject's loyalty. Such an investigation requires time and personnel.

Due to the peculiar nature of the Nisei cases which are now being submitted to the Civil Service by the War Relocation Authority, the committee believes that an even more thorough investigation should be conducted of these applicants. Yet War Relocation Authority officials, in their enthusiasm to relocate these people, are themselves now apparently seeking to have the Civil Service accept the War Relocation Authority's own assurances as sufficient to establish a subject's loyalty. To substantiate this, the committee includes in this report at this point a letter dated May 26, 1943, addressed to the Director of the Seventh Region of the United States Civil Service Commission, Chicago, Ill., from Elmer L. Shirrell, Relocation Supervisor of the War Relocation Authority.

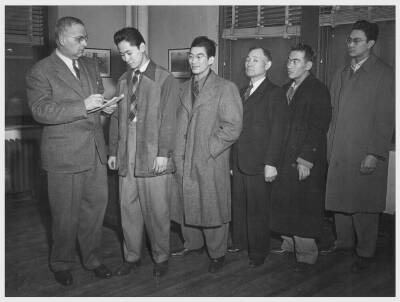

Chicago WRA supervisor, Elmer L. Shirrell, welcomes

five resettlers who have come to the Midwest. Chicago, Illinois. 1/6/44

Particular reference is directed to the following language contained in this letter:WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

Chicago, Ill., May 26, 1943.

DIRECTOR, SEVENTH REGION,

United States Civil Service Commission,

Chicago, Ill.

(Attention: Mrs. Klieger.)

DEAR SIRS: * * *, now residing at * * *, Chicago, Ill., and whose application for Federal civil-service employment is attached, has been given indefinite leave from the Granada relocation center. The fact that she has been given this leave is evidence that she has been thoroughly investigated and has been found loyal to the United States. The War Relocation Authority approves her placement in any city in Illinois or Wisconsin as these two States have been determined to be safe places for private and public employment for Americans of Japanese ancestry.

We will appreciate whatever assistance you can give in placing * * *.

Very truly yours,

ELMER L. SHIRRELL,

Relocation Supervisor.

The fact that she has been given this leave is evidence that she has been thoroughly investigated and has been found loyal to the United States. The War Relocation Authority approves her placement in any city in Illinois or Wisconsin * * *According to the present procedure of the War Relocation Authority, the only investigation which was made to determine this party's loyalty was the so-called questionnaire investigation made by the project director of the Granada relocation center.

The committee would like to emphasize that no Federal Bureau of Investigation "name check" or War Relocation Authority "home check" was made of this applicant. Nevertheless, an official of the War Relocation Authority certified to the Civil Service Commission that a thorough investigation had been made and the applicant was found to be loyal to the United States.

It is to just this type of loose and dangerous procedure on the part of the War Relocation Authority officials that this committee takes exception. The civil-service agents who are checking these applicants against the files of this committee have already determined that some of these applicants were members of and affiliated with organizations which were completely under the domination of the Japanese Government and so considered by every other investigative agency of this Government.

RECOMMENDATIONS

This committee recommends the following:

1. That the War Relocation Authority's belated announcement of its intention of segregating the disloyal from the loyal Japanese in the relocation centers be put into effect at the earliest possible moment.

2. That a board composed of representatives of the War Relocation Authority and the various intelligence agencies of the Federal Government be constituted with full powers to investigate evacuees who apply for release from the centers and to pass finally upon their applications.

3. That the War Relocation Authority inaugurate a thorough-going program of Americanization for those Japanese who remain in the centers.

MARTIN DIES, Chairman,

JOE STARNES,

JOHN M. COSTELLO,

NOAH M. MASON,

J. PARNELL THOMAS,

KARL E. MUNDT.

JOE STARNES,

JOHN M. COSTELLO,

NOAH M. MASON,

J. PARNELL THOMAS,

KARL E. MUNDT.

MINORITY VIEWS OF THE HONORABLE HERMAN P.

EBERHARTER

It is not possible for me to agree with the findings and conclusions of the other two members of our subcommittee, who constitute the majority.

After careful consideration, I cannot avoid the conclusion that the report of the majority is prejudiced, and that most of its statements are not proven.

The majority report has stressed a few shortcomings that they have found in the work of the War Relocation Authority without mentioning the many good points that our investigation has disclosed or the magnitude of the job with which the Authority is dealing.

Since the close of our hearings I have made some inquiries in order to clear up some points about which I was in doubt and on which the testimony did not seem to be sufficiently clear, the results of which inquiries have not been communicated to the other members of the subcommittee, because the subcommittee has never met to discuss the contents of a report.

There are a few basic matters that ought to be kept clearly in mind, which I wish to summarize here at the beginning before dealing with the body of the majority report of the subcommittee. It should be remembered that the relocation centers administered by the War Relocation Authority have been intended from the very beginning to be only temporary expedients. These relocation centers are not supposed to be internment camps. Dangerous aliens are placed in internment camps, but those camps are administered by the Department of Justice and should not be confused with the relocation centers. When the Japanese population was removed from the west coast they were at first free to go anywhere they wanted within the United States so long as they stayed out of the evacuated area. The first plan contemplated merely free movement and did not provide for any kind of relocation centers. For about a month thousands of evacuees were permitted to leave the west coast voluntarily for other parts of the country. Most of them have since continued to live anywhere they wanted to.

It was soon found not feasible to permit such voluntary movement to continue because trouble began to develop in places where people were not ready to receive these Japanese who had been ordered to move. It was then that the plan was changed to establish relocation centers in which the Japanese could live until it was feasible for them to get reestablished in normal life.

The dangerous aliens among the Japanese population on the west coast were picked up by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other agencies in the first few days after Pearl Harbor. Practically all the rest were presumed to be loyal and safe. It was necessary to evacuate the whole group, even after the dangerous aliens had been picked up and interned, because there was danger that the west coast would be invaded by the Japanese Army. But once removed from the west coast it was believed these people presented no further danger.

Dillon S. Myer, Director of the Authority, has told this subcommittee that about two-thirds of the people removed from the west coast are American citizens. Such a proposition as this, of moving approximately 70,000 American citizens away from their homes, has never been attempted before. Our Constitution does not distinguish between citizens of Japanese ancestry, or of German or Italian ancestry and citizens of English, Scotch, Russian, or Norwegian ancestry. Loyal American citizens of Japanese ancestry have the same rights as any other loyal American citizens. I believe the Government was entirely right, therefore, in permitting free movement from the west coast so long as that was possible, and then in providing relocation centers when that proved necessary. The whole point of the program is to help the loyal American citizens of Japanese ancestry, and the law-abiding aliens, to leave the relocation centers after investigation, and become established in normal life.

The rights of citizens to live as free men are part of the "four freedoms" for which we are fighting this war.

The testimony produced before this subcommittee shows that large numbers of the Japanese-American evacuees are working in war plants and in agriculture, and doing a good job. The Army has found that many of them are so trustworthy that they are being used in Military Intelligence and other secret work of high military importance. The evidence shows there were something like 5,000 loyal American citizens of Japanese ancestry in the Army before the evacuation. Early this year the Army organized a special combat team of Japanese-Americans which is now in training at Camp Shelby, and which is made up entirely of volunteers.

Life in the relocation centers is not a bed of roses. The houses are of plain barrack style. The food is adequate but plain. The great majority of the relocation center residents are working at necessary jobs in connection with running the camps. They are raising much of their own food. For this work they get paid, in addition to their keep, only $12, $16, or $19 a month. Even loyal American citizens in the relocation centers are working for these low wages.

Because of these facts I am disturbed about some of the ridiculous charges that were made early in our investigation. Stories about the Japanese people hiding food in the desert and storing contraband in holes under their houses, were shown to be ridiculous when a project was visited. However, the majority's report fails to withdraw these charges.

The report of the majority makes a big point about 23 persons who were released from the camps and who are found to be members of Butoku-kai, a Japanese fencing organization. This is 23 people out of 16,000 released. Even in the case of these 23 neither the majority report nor the hearings offer any evidence that any of the 23 were subversive.

I, for one, want to emphasize that just because a person is a member of an organization alleged to be subversive, I do not ipso facto conclude that the particular person is subversive. Certainly, mere proof of membership in an organization alleged to be subversive does not provide legal grounds for arresting or detaining such a person. Proper investigation may determine such a person to be intensely loyal to the United States.

After all the wind and the fury of a long report that creates the impression that the War Relocation Authority is doing a very bad job, the comments of the majority members are climaxed by three feeble, meaningless recommendations.

These recommendations hardly support the prejudiced tone of the report. I shall discuss them later. At this point I want to take up some of the specific matters discussed in the majority's report.

THE REPORT OF THE MAJORITY

Administration of relocation centers.

In the majority's report the following language appears:

This committee does not consider it necessary to discuss in detail the administrative errors and deficiencies of the War Relocation Authority, which were indicated by voluminous evidence received in the course of the subcommittee's hearings. The Director of the War Relocation Authority, Dillon S. Myer, was frank in admitting that many mistakes had been made. Only those administrative errors which bear directly or indirectly upon the subject of subversive and un-American activities come within the special interest of this committee.The implication of this paragraph is that the administration of the War Relocation Authority program has been lacking in competency and efficiency, that many mistakes have been made, and that Director Myer acknowledged that this was true.

Actually, Director Myer expressed the judgment before the subcommittee that a good job is being done in administration of the relocation centers and of the program as a whole and that such mistakes as were made, particularly in the early months of operation, were largely such as would inevitably occur in the development of a new and unprecedented program. There was nothing in the evidence heard by the subcommittee that would bear out the implication that the program was being incompetently or inefficiently administered. All things considered the preponderance of evidence indicates that the War Relocation Authority is doing a good job in handling an extremely difficult problem.

Fitness of War Relocation Authority personnel.

The majority's report states that much of the personnel in the War Relocation Authority is manifestly unfit for the job. The only specific evidence which is referred to in the report or which was presented before the subcommittee to substantiate this conclusion was the assertion that few of the administrative personnel had a prior knowledge of Japanese culture, language, and habits. Director Myer, in his testimony, states that the War Relocation Authority staff included some persons who were specially chosen because of their acquaintance with Japanese culture and language and that these persons had served as advisers to other members of the staff. A considerable number of the staff were formerly residents of California and other Western States who in the past had a great deal of contact with persons of Japanese ancestry living in this country.

The fact that apart from these two groups most of the War Relocation Authority staff had no previous close contact with Japanese or Japanese-Americans seems not particularly significant. For one thing, there are comparatively few people in the United States who understand the Japanese language or are well acquainted with Japanese culture. Apart from that, it would have been unfortunate had the War Relocation Authority sought to employ a large number of such persons when actually they would have been and are more usefully employed by other agencies of the Government engaged directly in the war against Japan. Furthermore, the War Relocation Authority would be subject to severe criticism were it dominated by people who have previously been intimate with the Japanese or Japanese-Americans and therefore subject to the accusation of being unduly sympathetic toward them.

Americanization.

Anyone genuinely interested in the problem of continuing the Americanization of the Japanese-American population of this country must acknowledge that the greatest force for Americanization is free, friendly, and continuous contact with non-Japanese-Americans in normal communities. The evacuation and isolation of the Japanese population in relocation centers away from normal contacts is an almost overwhelming obstacle to the assimilation of the Japanese-Americans, as it would be to any immigrant population. To say, as the majority's report does, that---

the War Relocation Authority had before it an almost unparalleled opportunity to inaugurate a vigorous program for positive Americanism---is an almost complete inversion of the true situation. Americanization is best accomplished not by formal programs of education, but by the continuous day-to-day mingling of the immigrant group among the general American population. By way of illustration, the story is told of an educated, loyal Nisei during the very early days of evacuation when his family was still in an assembly center, who protested bitterly that his children, who had always spoken good English, were learning broken English from their less well Americanized companions.

Far from having an unparalleled opportunity in the relocation centers to affect Americanization, the War Relocation Authority is confronted with the very difficult problem, under such artificial circumstances, of preventing the development of a distinct relocation center culture which is mostly American but partly Japanese. Anyone sincerely interested in the Americanization of the loyal Japanese must see that the best Americanization program is found in the relocation of evacuees in normal American communities.

The majority's report bases a strong criticism of the Authority on the fact that the Authority has carried on the evacuee pay roll at each center certain recreational supervisors who were especially concerned with sports and recreational activities of Japanese origin. Particularly, criticism has been directed against the teaching of Judo. Reference is made to the employment of 90 Judo instructors at one center. Director Myer explained that this overemphasis on Judo at that particular center had long since been corrected by the Authority. He also explained that such instruction in Judo as still continues at the centers is carried on under a program formulated after consultation with competent intelligence officers of the military service. It is a matter of common knowledge that Judo is taught to soldiers in the United States Army and that Japanese-Americans from the relocation centers are often used as instructors in Judo classes outside the centers.

It was also brought out in Director Myer's testimony that the teaching of Japanese language in the centers, originally prohibited, is now conducted largely for the benefit of persons who will become Japanese language teachers for the United States military and naval services.

As to the Americanized recreational activities, the evidence indicates that baseball is the most popular sport among the evacuees at the relocation centers. Basketball and football are also very popular. Boy Scout work, Girl scout work, and the like have a following multiplied many times over that accorded to similar activities of Japanese cultural origin. Among the evacuees there are many thousands of members of such organizations as the Young Men's Christian Association, Young Women's Christian Association, Girl Reserves, Hi-Y, Camp Fire Girls, and Future Farmers of America. A large proportion of the adult population belongs to parent-teacher associations, the American Red Cross, and similar organizations.

Evacuee food.

Among the complaints listed as reasons for this subcommittee's investigation is the charge that---

the Japanese evacuees were being supplied food through the Quartermaster Corps of the Army in greater variety and quantity than was available to the average American consumer.This charge is repeated in the report of the majority members but it is not brought out that the evidence received before the subcommittee completely rebutted the charge. The facts which the subcommittee's investigators established and which were borne out by other testimony received by the subcommittee are these:

1. All rationing restrictions applicable to the general public are strictly applied in relocation centers.

2. Food costs have averaged 40 cents per day per person and are subject to a top limit of 45 cents per day per person on an annual basis.

3. Director Myer testified, without contradiction, to the effect that the centers are instructed to refrain from purchasing commodities of which there are general or local shortages.

4. Within the limitations set by rationing and the 45-cent daily cash allowance, the Authority has provided an adequate diet meeting reasonable wartime standards.

Discipline in relocation centers.

Another of the complaints listed as reasons for the subcommittee's investigation was the charge that---

the discipline in the various relocation centers was very lax, and that considerable Government property had been destroyed by some of the Japanese.No specific comment is made concerning this complaint in the majority's report.

Actually, the evidence produced before the subcommittee indicated that there was much less crime of any kind in the relocation centers than in the average American community of the same size. By and large the evacuees have cooperated with the administration of the centers in maintaining order and discipline. Considering the emotional and social demoralization involved in evacuation, the conduct of the evacuees has been exemplary. The evidence indicates that ordinary crime at the centers has been negligible.

Manzanar gangs.

In the majority's report considerable space is given to certain activities attributed to the Blood Brothers Corps at Manzanar. Two statements are necessary in reference to this discussion. In the first place, it should be pointed out that the War Relocation Authority did, according to the evidence presented to the subcommittee, take rather effective action in handling these gangs. An isolation center was established and the gang leaders were transferred to that place. At present it appears that activities such as those of the Manzanar gangs have been eliminated. Secondly, the evidence concerning existence of the Blood Brothers Corps is very indefinite. No one has been discovered who belonged tot he supposed organization and the only evidence of its existence consists of certain apparently anonymous letters purporting to be written by a member of the corps. The point is that very little worth-while evidence is actually available on the existence of a Blood Brothers Corps. The evidence indicates that Manzanar probably had more troubles than any of the other relocation centers but the evidence also indicates that the sources of trouble there have now been eliminated.

Segregation.

In the majority's report the War Relocation Authority is severely criticized for not having entered upon a program of segregating disloyal evacuees from the great majority who are loyal before public hearings before this subcommittee had revealed the urgent need for segregation. Actually the facts are that on May 4, 1943, at a press conference in Washington, Director Myer announced the program of segregation and the announcement was given newspaper publicity. This was before the hearings of this subcommittee were begun and long before the United States Senate adopted the resolution referred to in the majority's report. Furthermore, Director Myer had in April written a letter to Senator A. B. Chandler, chairman of the Subcommittee on Japanese War Relocation Centers of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs, in which letter he stated that a program for such segregation was being worked out. Senator Chandler gave this letter to the press shortly afterward.

Had it been physically possible to make a fair determination immediately at the outset of the establishment of the relocation centers as to the loyalty or disloyalty of each evacuee, many of the difficulties of the War Relocation Authority would have been eliminated.

Nevertheless, I believe that the War Relocation Authority could and should have speeded up the plan for segregation more than it did. I feel that the actual movement of segregants should have been initiated more quickly. It is true that intelligent determinations on the loyalty of more than 100,000 people cannot be made in a week or a month and the War Relocation Authority's efforts to be fairly certain in its determinations are commendable. However, many of the evacuees who were known to be disloyal could have been moved out of the regular relocation centers sooner than was done. A certain amount of criticism on this point is therefore justified.

The legal aspects of the relocation program.

The constitutional difficulty of confining citizens not charged with any crime is not discussed in the majority's report. Legality of such detention becomes increasingly difficult to sustain when it involves citizens of the United States against whom no charges of disloyalty or subversiveness have been made, particularly, if the detention continues for a period longer than the minimum time necessary for ascertainment of the facts. The principal justification for detaining citizen evacuees in relocation centers is that such detention is merely a temporary and qualified detention. They are detained until they can be sifted with regard to their sympathies in the war and until jobs can be found for them in communities where they will be accepted.

Such action may be sustained as an incident to an orderly relocation program, but any unqualified detention for the duration of the war of loyal citizens would be so vulnerable to attack in court as to imperil the entire relocation and detention program. That the leave regulations are legally necessary is emphasized by a recent decision of the Federal court for the northern district of California which dismissed a petition for writ of habeas corpus brought by an evacuee, on the ground that petitioner had not exhausted her administrative remedies by applying to the War Relocation Authority for leave (In re Endo).

In Hirabayashi v. United States, decided on June 21, 1943, the United States Supreme Court heard an appeal by a citizen of Japanese descent who had been sentenced concurrently on two counts: First, for violation of curfew regulations, and secondly, for failure to report for evacuation. The Court sustained the conviction solely upon the basis of the curfew count and avoided consideration of the conviction on the evacuation count. The natural inference that the Court found it comparatively easy to uphold the curfew, while encountering comparative difficulty in determining the legality of the evacuation, is reinforced by passages in concurring opinions by Mr. Justice Murphy and Mr. Justice Douglas. Mr. Justice Murphy, in his concurring opinion, said of the curfew orders:

In my opinion this goes to the very brink of constitutional power.Since the detention accompanying the evacuation is a more drastic restriction of liberty than the mere evacuation itself, there is even more reason for the opinion that such detention is to be justified under the Constitution only if it is carefully limited with all possible respect to the rights of citizens in the current emergency. The legal problems of detaining citizens cannot be disregarded by the governmental agency responsible for administering the leave program.

It is apparent that the leave program of the War Relocation Authority has been formulated with a thoughtful view toward assuring the legality of the Authority's program as a whole, and it is probable that without the leave program the whole detention plan might well be subjected to successful legal attack. That this protection against such attack has been set up and put into effective operation, thus giving greater assurance of the continued detention of those who under the program are not entitled to leave, is a fact for which the Authority is definitely to be commended.

Leave program for the War Relocation Authority.

A principal object of the War Relocation Authority's leave program, it seems, is the separation of evacuees believed to be loyal to Japan from those loyal to the United States. This is the same thing substantially as the segregation program. The best way to segregate the disloyal from the loyal is to relocate the loyal in normal life. That is what the leave program is designed to achieve. This takes time, however. It seems unfair to the loyal, in the meantime, to allow them to be confused in the public mind with the disloyal, therefore, segregation should be and is being undertaken as a separate program. As soon as segregation is completed it seems that the leave program itself for the loyal evacuees should be substantially speeded up.

Administration of leave program.

On October 1, 1942, the present basic leave regulations of the War Relocation Authority became effective, on publication in the Federal Register. They provide that any evacuee citizen or alien may request indefinite leave from a relocation center. To support the request, the evacuee must show that he has a job or can take care of himself, must agree to report changes of address to the War Relocation Authority, and must have a record indicating that he will not endanger the national security. In addition, the War Relocation Authority must satisfy itself that the community in which the evacuee proposes to relocate will accept him without difficulty.

Much of the substance of the majority's report is concerned with the problems of releasing evacuees from relocation centers. The essential question raised by the report is whether or not the War Relocation Authority has exercised reasonable precautions and careful judgment in determining which evacuees shall be granted leave. The majority's report concludes that it has not. As evidence for its conclusion, it relies chiefly upon two arguments: (1) 23 evacuees who have been given leave from the centers may be dangerous because they had some connection with an allegedly subversive organization known as Butoku-kai; (2) the present procedures of the Authority do not provide sufficient checks on the record of individuals released.

As to the first of these arguments, the majority's report does not allege that these 23 members of the Butoku-kai are subversive or dangerous, but does state that---

The release of these 23 Japanese is evidence of the incompetence of the War Relocation Authority to exercise proper safeguards both for the national security and for the thousands of loyal Japanese as well.In a letter dated July 16, 1943, to this subcommittee, Director Myer gave specific information concerning the circumstances under which leave was granted to these 23 persons. It was brought out that, as to 16 of the 23, the Federal Bureau of Investigation had records which disclosed no report or derogatory information. As to 5 of them, the Federal Bureau of Investigation had no records whatever. One was released for school work under an agreement with military intelligence. One, an alien, was paroled, under the regular sponsor parolee agreement prescribed by the Immigration and Naturalization Service of the Department of Justice. That accounts for all 23 of them. Director Myer states that no evidence was given to the Authority either from the Federal Bureau of Investigation or any other agency that any one of these 23 persons was dangerous or subversive.

Leave clearance procedure.

The second major argument advanced in the majority's report in support of its strong condemnation of the leave clearance procedures followed by the War Relocation Authority is that procedures have recently been so liberalized as to remove certain essential safeguards. It is stated that while originally the Authority made what is called a home check and a name check and all leave clearance was granted by the Director in Washington, since April 1943 project directors have been authorized to "make their own determination (with certain limitations)" as to the release for indefinite leave of an evacuee and that the home check and the name check have been eliminated. ("Name check" is the term used by the subcommittee to describe the process of securing such information as is available in the records of the Federal Bureau of Investigation before granting leave to an individual.)

This statement is misleading in three respects. In the first place, "the certain limitations" are extremely important in that they withhold the right of the project director to grant leave to the following categories of people:

1. Evacuees who answered no or gave a qualified answer to the loyalty question during the Army registration.

2. Repatriates and expatriates.

3. Paroled aliens.

4. Shinto priests.

5. Those whose leave clearance has been suspended by the Director.

These categories include all evacuees about whom there is generally reason to have doubt. That these "certain limitations" are in force is established by the provisions of the Administrative Instruction (No. 22) given in evidence, and by the direct testimony of Director Myer before the subcommittee.