This site is about the Prisoner of War camp that was in

Fukuoka during World War II. It was first located in Kumamoto from late

1942 and moved to three

other locations in Fukuoka City over a period of nearly two

years, from November 1943 until September 1945. Over 1000 American,

British, Dutch, Australian, Canadian and Norwegian POWs were interned

at Camp #1 during those years. Nearly 200 of those died here.

In the following pages you will read actual reports

from those who were at Camp #1, not only Allied affidavits used at the

International Military Tribunal for the Far East, but testimonies from

the Japanese as well, to help the reader assess both sides of the

story. I have neither deleted nor abbreviated any of the names or

facts. Declassified documents from the National Archives, Washington,

D.C., were scanned, run through OCR software, checked, and then retyped

where necessary. Typos are original, though some may be unintentionally

mine. Minor spelling changes have been made, though I did keep the

original spelling of the Japanese names with the proper spelling placed

between brackets [ ]. Notes that I've added here and there are also in

brackets.

For those of you who once lived in Fukuoka, after

reading these reports, testimonies, interrogations and affidavits, you

will no doubt get a different perspective on the city. I know every

time I passed by Fukuoka International Airport, I would think about

those who suffered building that airstrip, and those who rejoiced in

finding frogs, snails or grasshoppers in the rice fields, making for a

delicious roasted meal.

If you are a foreigner living in Japan, come August you

will be sure to notice the emphasis in the media regarding Hiroshima

and Nagasaki and the terrible A-bombs. Hopefully these pages I've put

together will add additional perspective.

I wanted to make this webpage in order to remember

those POWs who suffered here, in the city I have called home for the

past quarter century. Eventually I hope to place memorial plaques at

each of the former camp sites, cemeteries and crematoriums. It is

worthy that we remember those who unwillingly had to sacrifice so much

of their lives, both physical and mental suffering, much of which has

not healed even after all these years. We who never experienced war

will never really understand perhaps. But we can learn from what they

have written. Quite often while reading through and retyping these

affidavits I have been driven to tears, to the point of sobbing out

loud, and in a eerie way feeling as if I were there myself -- shivering

with the freezing, bleeding with the beaten, languishing with the sick,

enduring with the hopeful ones.

|

Prayer

for Prisoners of War

Look, O Lord God,

with the eyes of Thy mercy, upon all prisoners of war, especially those

known and loved by us. Preserve them in bodily health and in cheerful,

undaunted spirit.

Convey Thou to

them the support of our love on the wings of Thine own and hasten the

day of release; through Him who hath made us free eternally, Thy Son,

our Savior, Jesus Christ. Amen.

(This daily prayer for

prisoners of war was recently heard for the first time at St.

Margaret's, Westminster, in London, at a special service of

intercession. Written by the Dean of York, Rev. E. Milner-White, for

the Red Cross, it has now been adopted for general use in churches in

England. The prayer is based on the Second Epistle of St. Paul to the

Corinthians, chapter 3, verse 17: "Where the spirit of the Lord is,

there is liberty.") Source: American National Red Cross, Prisoners

of War Bulletin, Vol. 1 #2 July 1943

|

I do realize that the plight of the POWs in Japan is by

no means the worst of actions that man has leashed out on fellow man.

Were we to gather all the facts on the treatment of prisoners of

oppression throughout the centuries and milleniums, then we can make a

fair assessment of what was atrocious and what was justifiable, e.g.

guards beating POWs ferociously after an air raid. Worldwide, millions

have suffered and died at the hands of their captors. The POWs in Japan

were not unique. One only has to go back a few years, perhaps even only

a few months, or even weeks, to find similar atrocities that have

occurred around the world. Yuki Tanaka in his book Hidden

Horrors describes this well in his introduction, which you

can read below. If you were to mention the names of Auschwitz,

Buchenwald, Dachau to someone, they can probably associate these places

with atrocities. In contrast, mention Bataan, Sandakan, or

Kanchanaburi, and you will more than likely be greeted with blank

stares.

It must be stated emphatically that not all Japanese

commandants, guards and personnel were cruel towards their captives.

One former commandant,

now living in Fukuoka, treated POWs at the Nagasaki camp in a humane

manner. Cecil Parrott

tells of a number of Japanese who were kind to him. It's also worth

noting that not only were the Allies treated horribly as POWs, the

Japanese themselves were victims during the war -- some 600,000 being

imprisoned in Russian POW camps. Those who are loose with the epithet

"Japan-bashing" should read those accounts.

The following first-person accounts will certainly

reach deep, no matter what country you may be from. Naturally, as for

me, I think of those Americans who were here in Fukuoka. These were

some of my fellow countrymen, in a strange land with a strange

language, strange food and customs, away from everything they were used

to, being forced to live on the edge of what could barely be called

life, not knowing whether they would ever see their homeland again, nor

even when their last day would be. Just think of the daily routine

these men had to go through of not knowing what would happen to them --

day after day after day after day. The hope and fortitude of those who

survived, in the face of such depravity, is surely a quality we who are

more fortunate know very little of.

I am most aware and sensitive of the fact that there

are some ex-POWs that have no desire at all to remember those wretched

years of captivity, much less talk about their experiences. Past is

past -- they have gone on with their lives. It is not my desire to

bring up any painful memories, believe me.

Yet there are many former POWs who are now beginning to

write of their experiences and share their memories, and I am so glad

they have made that decision to share. The number is growing each year.

It could be that their children and grandchildren are encouraging them

to do so, or perhaps it is simply a final effort to deal with their

past, a form of ultimate therapy, so to speak. It's interesting that as

one gets older the desire to "leave a legacy" becomes stronger. We all

want others, especially our kids and grandkids, to know about what we

accomplished in life, the good we did, the sacrifices we made, so that

they can learn from our experiences and advice and hopefully avoid the

mistakes we made. It seems so many kids these days have made heroes out

of fantasy characters from the entertainment world. But here are some

real heroes for the youth of today.....

I think of George

Idlett..... Cecil

Parrott..... Lester

Tenney..... Frank

Lovato..... Don Versaw.....

Rodney Kephart.....

All these men, all ex-POWs, have recently written their

memoirs. I'm sure it was painful, yet they felt the need to tell others

about that pain. The remarkable thing I find in their recollections is

that they have no hate at all towards their former captors. In fact,

some of their closest friends now are Japanese.

They and so many thousands of other ex-POWs like them

know exactly what freedom is. Just ask them. Their love of that

cherished principle we take for granted can be seen so clearly as you

speak with them. August 1945 marked a special time in their lives.

Inwardly they surely must celebrate the day of their liberation with

more elation than any other day. Let us also, though, remember those

who have yet to experience their complete liberation from those

unspeakable memories.

"Finally,

finally,

finally,

someone has taken the time to pay attention."

--- Gavan Daws on main gist of letters from POWs,

in an article by James Dao

Here is an excellent tribute to all

former POWs from the July 2001 issue of The Quan. Their story must be told!

REMARKS

by Hon. Anthony J. Principi

Secretary of Veteran Affairs

American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor

Hampton, VA

May 19, 2001

The

great historian David McCullough has written: "History is a guide to

navigation in perilous times." It is easy for today's statesmen to

chart an incorrect course by confusing a cinematic version of the war

with the war's true history. Hollywood would have it that an aroused

nation, awakened to its peril, armed itself after Pearl Harbor and

achieved victory after glorious victory, culminating in the Japanese

surrender on the battleship Missouri.

It is easy to tell the

story of our involvement in World War II as a tale of inevitable

victory. But that would result in a false understanding of history,

because it would omit the contribution that men and women like you made

at a time when our victory was far from certain. And your contribution

is a story that needs to be told.

Your story includes the

heroism of the 31st infantry regiment, and the 4th Marines, and the

28th Bomb Group, and the sailors at Cavite, and the other brave

American men and women stationed throughout the Western Pacific on

December 7, 1941.

All of these men and women woke up on December

8 cut off from their country and the world -- without a realistic

chance to defeat the enemy if they were not reinforced; without a

realistic prospect of receiving that reinforcement; and even without a

realistic chance to be evacuated.

Every new generation needs to

be told that Americans lived and fought in 1941 and 1942 with no chance

of victory for themselves, but with only the hope of delaying the enemy

while our nation woke up to the consequences of war.

Every new

generation needs to be told that three days after Pearl Harbor, the

Japanese sent three cruisers, six destroyers, and four transport ships

to attack the four hundred and forty-nine Marines on Wake Island. And

that the attackers were driven off by those Marines, and only a second

attack group with heavy cruisers, more destroyers, two aircraft

carriers and thousands of Japanese Marines could defeat these men.

At

the beginning of the war, only you and your comrades stood between the

enemy and victory. And you held the line, and did so magnificently,

even at a terrible cost. As General Mac Arthur said: "The Bataan

Garrison was destroyed due to its dreadful handicaps, but no Army in

history more thoroughly accomplished its mission."

Without you,

the sacrifices of the crew of the Arizona would have been in vain. The

Doolittle raid would have been an empty gesture. And the name of Dorie

Miller would have long been forgotten.

I am reminded of the

words of President John F. Kennedy. He said: "Without belittling the

courage with which men have died, we should not forget those acts of

courage with which men have lived. The courage of life is often a less

dramatic spectacle than the courage of a final moment, but it is no

less a magnificent mixture of triumph and tragedy."

Many men died at Pearl Harbor, at Wake Island, at Bataan and Corregidor, and throughout the Pacific theatre of war.

Many who were taken captive along with you died in the course of their captivity.

Next

weekend, on Memorial Day, we will once again honor those who died

alongside you, as we honor all our war dead. We honor them for their

faithfulness to our nation, for their service and sacrifice, and for

their unsurpassed courage.

But we must also honor you, who fought so valiantly and endured so much in the name of freedom.

Your story of steadfastness and loyalty again needs to be told.

We

must again tell the story of Bataan and Corregidor: of the 10,000

Americans of Bataan who surrendered and were led on the Bataan death

march, the thousand who died -- and the 9,000 who survived to face

years of brutal and deadly captivity.

We must again tell the

story of the men of Corregidor, kept prisoner for three and one half

years, and all who were held by the Japanese in conditions so horrible

that more than 87% of all those imprisoned died in captivity.

We

must remind a new generation of the slave labor you were forced to

endure, and the cruel and unusual punishments, and the medical

experiments.

Your story must be told because your courage -- and your heroism -- was what led us on to victory.

Most Americans have no idea what it is like to be in combat.

But you have all known combat -- both the physical kind, and the special kind that a prisoner of war faces.

In

combat, the enemy is largely unseen. He is somewhere out there, until

the moment the shooting begins, and even afterwards. And when the

shooting stops, the battle stops. There are opportunities for a hot

meal, for a furlough, even for reassignment once physical limits are

reached.

But to a prisoner of war, the enemy is everywhere. He

controls your fate, your future, even your bodily functions. You are at

war at every second. Your diet is always the same. You are never given

leave. You can never leave the combat zone. Even today, more than

fifty-five years after the end of your captivity, your lives are still

shaped by your experiences.

Your victory was measured in your

survival; and in maintaining your faith and your loyalty to your

country, when the reward for maintaining that loyalty was continued

starvation -- and death.

Your strong heart, great spirit, and

unyielding faith served as an inspiration to the rest of us. You placed

honor before everything, even before having a whole self.

You

absorbed with your own bodies the blows that were intended by our

enemies for our nation and its people, and you sacrificed your own

freedom for the freedom of the world.

And finally, you returned

from your service, regained your rightful place in our society, and

strengthened your families, your communities, and our nation through

your example of courage, and loyalty and continued good citizenship.

Your role in rebuilding America after the war is a story that also must be told.

We at the Department of Veterans Affairs honor your service, and are grateful for your sacrifices.

As

former Prisoners of War, you are entitled to special benefits from our

department. We recognize that the physical hardships and psychological

stress you endured in your captivity has had a life-long effect on the

health of many of you, and on your readjustment to society.

We

provide compensation for many disabilities that may have been brought

on by your captivity -- and are still looking for other linkages that

may become manifest as you age.

Our national outreach program

works to educate all former prisoners of wars about VA benefits and

services you may be entitled to.

And it is my highest priority

as Secretary to improve the timeliness and accuracy with which we

process benefits claims, both yours and those of every other veteran.

Some

of you may know that it now takes nearly nine months for us to process

the average claim for benefits. You have earned better service than

that. And you will get it.

Let me conclude with the words of television commentator Tom Brokaw. I'm sure most of you know his book, The Greatest Generation.

It is about the men and women who, like you, came of age in the 1940's.

This generation heard first-hand of your ordeals; was inspired by your

example, and rejoiced at your freedom.

You are among the greatest of the greatest generation. This is what Brokaw wrote of you, and those who served with you: "At

a time in their lives when their days and nights should have been

filled with innocent adventure, love, and the lessons of the workday

world, (American soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines and Coastguardsmen)

answered the call to save the world from the two most powerful and

ruthless military machines ever assembled, instruments of conquest in

the hands of fascist maniacs. They faced great odds and a late start,

but they did not protest. They succeeded on every front. They won the

war; they saved the world."

So do not despair if you go to see

the movie about Pearl Harbor, and you do not recognize yourself and

your experiences in Hollywood's depiction of your war.

Remember

that others know of your loyalty to our country, your contribution to

our victory, and the many sacrifices you have offered for her freedom.

And of the strength you showed in resisting the enemy despite hopeless odds, and in continuing to resist despite your captivity.

When

they were asked what they needed, they asked only one thing. "Send us

more Japs," the commanding officer said. "Send us more Japs."

And

though these American troops knew that they faced certain captivity or

death, they fought as bravely and as well as any man in the United

States has ever sent into battle. Fifteen hundred Japanese were killed

in the assault on Wake Island. Only forty-nine Marines and three

sailors died.

And every new generation needs to be told that

fifteen days after Pearl Harbor, in Lingayen Bay, the Japanese

fourteenth army invaded Luzon. And though desperately short of food,

medicine and ammunition, the Battling Bastards of Bataan and the

defenders of the Rock fought ferociously until the following May.

Those

who fought on Bataan and Corregidor did more than resist the enemy to

the utmost of their ability. They stopped the Japanese in their tracks,

and gave our nation precious time to recruit and train the men and

women who would eventually win the war -- and build the ships, planes

and guns that were the tools we needed to win.

And they rallied

a nation made fearful by Pearl Harbor -- and reminded our citizens that

the American fighting man was the equal, or the superior, of any other

fighting man on the face of the earth.

The Japanese won great

tactical victories at the beginning of the war. We were not ready for

the preparations a totalitarian nation, shaped by leaders who glorified

war, had made for conquest.

Remember, too, that our ultimate

victory in World War II, and our continued prosperity today, rests in

no small measure on your accomplishments during that war.

And

that the tales of your great heroism will be told, again and again,

from generation to generation, for as long as our republic shall stand.

You

are but mortal men and women, but your steadfast courage and dedication

gave you the strength to achieve immortal acts. And those acts must be

acknowledged in perpetual stone.

Your story, your service, and

your sacrifice are irrefutable testimony that a memorial to the

veterans of World War II must be built on the National Mall in

Washington -- now!

May God bless all of you.

Be sure to visit the American Defenders of Bataan

& Corregidor site, and also the ADBC Descendants Group website.

|

A. Gibbs

Report

A. Gibbs

Report ![]() Standard report of July 31, 1946

Standard report of July 31, 1946  B. Summary of

Investigation of POW Camp 1

B. Summary of

Investigation of POW Camp 1 ![]() Ramey investigation report of January 8, 1946

Ramey investigation report of January 8, 1946  C. Progress

Report Re Investigation of Camp Number 1

C. Progress

Report Re Investigation of Camp Number 1 ![]() Ramey and Humphreys report of January 6, 1946

Ramey and Humphreys report of January 6, 1946  D. Metcalf

Affidavit

D. Metcalf

Affidavit ![]() British POW's description of Kumamoto, Kashii and

Mushiroda camps

British POW's description of Kumamoto, Kashii and

Mushiroda camps  E. Vesey

Affidavit

E. Vesey

Affidavit ![]() British POW's description of Kashii and Mushiroda

camps

British POW's description of Kashii and Mushiroda

camps  F. Saunders

Affidavit

F. Saunders

Affidavit ![]() British POW's (Chief Commanding Officer)

description of all four camps

British POW's (Chief Commanding Officer)

description of all four camps  G. Kostecki

Affidavit

G. Kostecki

Affidavit ![]() American POW's (Chief Medical Officer)

description of Kashii, Mushiroda and Hakozaki camps

American POW's (Chief Medical Officer)

description of Kashii, Mushiroda and Hakozaki camps  H. Cooper

Report

H. Cooper

Report ![]() Excerpts from an American surgeon's report on

medical activities at Camp #1

Excerpts from an American surgeon's report on

medical activities at Camp #1  I. Lee

Affidavit

I. Lee

Affidavit ![]() British POW's description of Kumamoto, Kashii and

Mushiroda camps

British POW's description of Kumamoto, Kashii and

Mushiroda camps  J. Goodpasture

Check List

J. Goodpasture

Check List ![]() American POW's description of Hakozaki camp

American POW's description of Hakozaki camp  K. Memorandum

re Photos of Hakozaki Camp

K. Memorandum

re Photos of Hakozaki Camp  A. POW

A. POW

B. Japanese

B. Japanese

C. POW

Statistics

C. POW

Statistics  A. Vivisections

at Kyushu Imperial University

A. Vivisections

at Kyushu Imperial University

1. Articles on the crash, the vivisection

experiments, and the memorial

1. Articles on the crash, the vivisection

experiments, and the memorial

2. Statement by pilot, Marvin Watkins

2. Statement by pilot, Marvin Watkins

3. Interrogation

of Marvin Watkins

3. Interrogation

of Marvin Watkins

4. Watkins Statement of December 10, 1948

4. Watkins Statement of December 10, 1948

5. Letter from Marvin Watkins to Mrs. Dale

Plambeck

5. Letter from Marvin Watkins to Mrs. Dale

Plambeck

6. Message from Marvin Watkins to Taketa City

6. Message from Marvin Watkins to Taketa City  B. Beheading

of airmen

B. Beheading

of airmen

1. At Fukuoka Municipal Girls' High School

1. At Fukuoka Municipal Girls' High School

2. At Aburayama

2. At Aburayama

a. Interrogation

of Itaru Bajiri re August 10, 1945 incident

a. Interrogation

of Itaru Bajiri re August 10, 1945 incident

Summary of Japanese War Crime Tribunal

sentencing of Japanese personnel for Vivisection

and Aburayama incidents

Summary of Japanese War Crime Tribunal

sentencing of Japanese personnel for Vivisection

and Aburayama incidents  C. B-29

crashes & airmen killed

C. B-29

crashes & airmen killed

1. Interrogation

of Gunji Haraguchi re B-29 crash in Yokoyama, Yame-gun

1. Interrogation

of Gunji Haraguchi re B-29 crash in Yokoyama, Yame-gun

2. Air

Strikes against Fukuoka & Kyushu (TARGET: FUKUOKA)

2. Air

Strikes against Fukuoka & Kyushu (TARGET: FUKUOKA)  D. Bataan

Death March

D. Bataan

Death March

1. Death March Tales by Ray

Thompson

1. Death March Tales by Ray

Thompson

2. Bataan by George Idlett

2. Bataan by George Idlett

3. My Hitch in Hell by Lester

Tenney

3. My Hitch in Hell by Lester

Tenney  A. American

A. American  Affidavits A

- C

Affidavits A

- C  Affidavits D

- H

Affidavits D

- H  Affidavits J

- P

Affidavits J

- P  Affidavits R

- W

Affidavits R

- W  The Hansen Story

The Hansen Story

The

Shreve Diary

The

Shreve Diary  Lt.

Col. Jack Schwartz, Medical Officer

Lt.

Col. Jack Schwartz, Medical Officer  B. British

B. British  Affidavits A

- D

Affidavits A

- D  Affidavits E

- L

Affidavits E

- L  Affidavits L

- W

Affidavits L

- W  Capt.

William P. Wallace, Royal Army Medical Corps

Capt.

William P. Wallace, Royal Army Medical Corps  Reuben

Eastham, Bombardier

Reuben

Eastham, Bombardier  C. Dutch

C. Dutch  Medical

Officer Jan Frederik de Wijn

Medical

Officer Jan Frederik de Wijn  Gerry

Nolthenius

Gerry

Nolthenius  D. Australian

D. Australian  Pte.

Jack Dilger

Pte.

Jack Dilger  Sgt.

Peter French

Sgt.

Peter French  Gnr.

Geoffrey Underwood

Gnr.

Geoffrey Underwood  A. Commandant:

Yuhichi Sakamoto

A. Commandant:

Yuhichi Sakamoto ![]() Summary of Information, Oct. 22, 1945;

Interrogation of Oct. 29, 1945

Summary of Information, Oct. 22, 1945;

Interrogation of Oct. 29, 1945  B. Medical

Officer: Masato Hada

B. Medical

Officer: Masato Hada ![]() Affidavit of Jan. 2, 1946; Review of the Trial of

Masato Hada

Affidavit of Jan. 2, 1946; Review of the Trial of

Masato Hada  C. Interpreter:

Takeo Katsura

C. Interpreter:

Takeo Katsura ![]() Lengthy handwritten affidavit of January 20, 1946

Lengthy handwritten affidavit of January 20, 1946

D. Guard:

Hajime Honda

D. Guard:

Hajime Honda ![]() Interrogation of May 28, 1946

Interrogation of May 28, 1946  Summary of Japanese War Crime Tribunal

sentencing of Japanese personnel in Fukuoka

Camp Group

Summary of Japanese War Crime Tribunal

sentencing of Japanese personnel in Fukuoka

Camp Group ![]() A. Prisoner of War Supply Missions

to Japan

A. Prisoner of War Supply Missions

to Japan ![]() B. Prisoner of War Encampments

B. Prisoner of War Encampments

![]() C. Recovery

and Rescue of Prisoners of War

C. Recovery

and Rescue of Prisoners of War ![]() D. John

Bankston Collection -- Photos from Nagasaki, Sept. 1945

D. John

Bankston Collection -- Photos from Nagasaki, Sept. 1945

![]() E. Arrowhead

Pictorial -- Occupation of Japan by 2nd Marine Division

E. Arrowhead

Pictorial -- Occupation of Japan by 2nd Marine Division

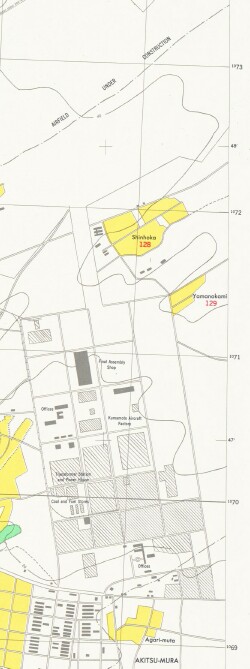

![]() F. Fukuoka Targets

- Japanese Air Target Analyses

F. Fukuoka Targets

- Japanese Air Target Analyses ![]() G. Kyushu Airplane

Company Report

G. Kyushu Airplane

Company Report ![]() H. Civilian Internment Camps in

Japan

H. Civilian Internment Camps in

Japan ![]() I. Chronology Chart of

Civilian Internment Camps: Internee Strength & Movement

I. Chronology Chart of

Civilian Internment Camps: Internee Strength & Movement

![]() J. Foreign Resident Population

in Japan: Nationality and District of Residence

J. Foreign Resident Population

in Japan: Nationality and District of Residence  A. Lawsuits

A. Lawsuits

B. Memorials

B. Memorials

1. Mizumaki Cross Memorial

1. Mizumaki Cross Memorial

2. Soto Dam

2. Soto Dam

3. Taketa "Sky Martyrs" Monument

3. Taketa "Sky Martyrs" Monument

4. Sanko Peace Park

4. Sanko Peace Park

5. Takachiho "Prayer for Peace" Monument

5. Takachiho "Prayer for Peace" Monument

6. Kihoku Crash Site Monument

6. Kihoku Crash Site Monument

7. Naoetsu Peace Memorial Park

7. Naoetsu Peace Memorial Park

8. Japan-U.K. Friendship Monument, Mukaishima

8. Japan-U.K. Friendship Monument, Mukaishima ![]()

![]() 9. Emukae Memorial, Fukuoka Camp #24

9. Emukae Memorial, Fukuoka Camp #24

![]()

![]() 10. Nagasaki Memorial, Fukuoka Camp #14

10. Nagasaki Memorial, Fukuoka Camp #14

Other

Memorial Sites in Japan

Other

Memorial Sites in Japan

B-29

Memorial Sites elsewhere in Japan

B-29

Memorial Sites elsewhere in Japan  C. Assorted

Articles and Pages

C. Assorted

Articles and Pages  Cecil

Parrott

Cecil

Parrott  Neil

MacPherson

Neil

MacPherson  Gerry

Nolthenius

Gerry

Nolthenius