THE PETER HANSEN STORY

by Gerard Moran

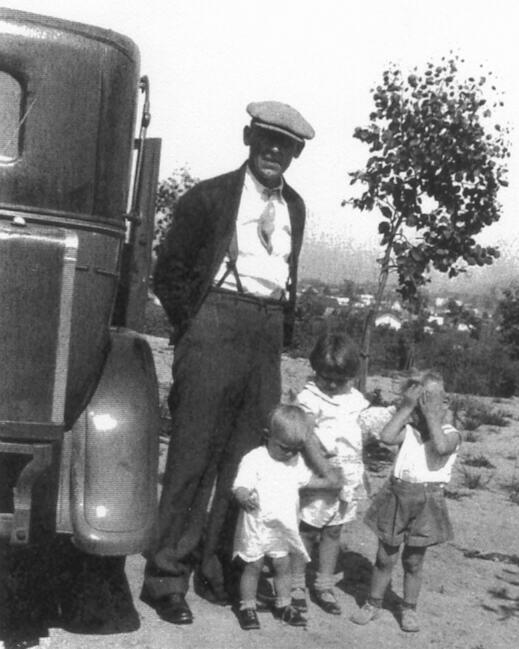

Peter W. Hansen, c. 1930

FINDING DAD

It was a tough decision but in the end it would help their situation considerably. Bernice Hansen would take care of the three kids, Harriet, Mary-Anne and John, while her husband, Peter Hansen, went to work overseas to make good money. When he got back they would have a nice bank account with much more money in it than if he had stayed in the States and worked.

His contract with the Morrison Knudsen Company was in days, two hundred and ninety two of them and the money had built up in savings, less what Bernice had been using to maintain things at home. The construction project he was assigned to had been underway since January and he joined it a little later in late March when it had been up-scaled from an eight-hour, five day per week project to one that was ongoing around the clock, seven days a week. He was making more money that he had imagined. The days, weeks and months passed quickly. Soon he was scheduled to fly home.

Bernice Hansen couldn't wait. In just under three weeks her husband would be home and their children would again see their Daddy. The family could get on with their lives together. Peter Hansen was counting down the days in the upper right hand corner of his letters. His last letter noted 273 days down just 19 to go before his December 23rd ticket home. The family would be able to spend Christmas together.

Hansen with children, Mary-Anne, Harriet and John

But that family Christmas never happened .......you see, Peter was a civilian contractor working for the United States Navy on Wake Island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and the year was 1941.

However difficult Bernice Hansen thought she had it, raising three kids alone for the past nine months was a walk in the park compared to what she was about to face.

Wake Island is way out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It's strategic importance became obvious after Pan American Airways began flying its famed Clipper service from San Francisco to the Philippines and China in November, 1936. Using stops in the Hawaiian Islands, Midway Island, Wake Island and Guam Island spread over six days the Pan American Clippers completed their journey after 60 flying hours. That was a marked improvement over the three week steamship trip that was standard until the Pan American Clippers had brought the Orient closer.

The U.S. Navy, which administered the Islands, saw the implications and began the construction project of which Peter Hansen was a part. It was a long budgetary process and then plans had to be drawn and contracts signed. Construction did not start until 1941. The initial plan called for facilities for PBY seaplanes and some submarines. There were also plans for the construction of an airfield. The Navy's strategy was to use Wake Island to secure Hawaii from intrusions and to protect the line of communications to the Philippines which at that time was under American control, a result of the Spanish American War.

Three days after Peter Hansen wrote his wife the letter telling her ..it won't be long now, ...good-bye to all, for this time, the construction crews, military and civilian, working on Wake Island facilities were given a rare day off as they had worked hard non-stop over several weeks. The day was a Sunday.

Peter, John, Harriet, Mary-Anne, George (Bernice's

brother), c. 1940.

In back of house Peter built near Miner's Field (now LAX).

Wake Island is on the west side of the International Date Line and thus it was one day ahead of the United States, that Sunday was December 7, 1941. The next morning word quickly spread of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The work crews were awakened with the news and quickly jumped to do what was needed. The battle stations on the island were still under construction as were the airbase facilities. Efforts were made to get them ready for what was surely coming. Civilian contractors with military experience reported to the U.S. Marine Corps commanders to offer assistance, other civilians were organized and redirected to finish defensive positions.

At noon the Japanese came to Wake Island. Twenty seven Japanese bombers shook the island and the Americans into the reality that war had come to their remote and isolated outpost. The Japanese bombers concentrated their efforts on the under-construction air field. Seven of the eight aircraft on the ground were destroyed, most when the main fuel dump exploded and spread 80,000 gallons of gasoline all over the runways. Some aircraft escaped damage since they were in the air at the time of the attack. It was just a matter of time before there was ground follow up. On December 11th, a Japanese naval task force was observed positioning itself to support a landing force invasion. USMC shore batteries with accurate fire sank one destroyer, damaged two cruisers, two destroyers and a transport ship. The three or four American aircraft that were in the air at the time of the Japanese bomber attack were able to sink another destroyer. The Japanese pulled back to soften up the island. For eleven days Wake Island was bombarded, destroying all above ground facilities. The remaining military aircraft that had been spared during the bomb attack were spared no longer - all were destroyed.

A U.S. Navy Task Force was enroute to Wake Island with re-enforcements. It was within 425 miles of the island when word came on December 23rd, the day Peter Hansen was to have left Wake Island, the Japanese had mounted a full scale invasion and had overrun and taken control of the island.

Two aircraft carriers, additional destroyers and cruisers a seaplane tender and other, smaller ships were in the Japanese Naval Task Force. One hundred and nine Americans died defending Wake Island, 47 of them civilian workers. Japanese losses were estimated at 700 men.

There were about 1,500 American men on Wake Island during the battle. Only 400 0f them were military. The civilian work force had done well in helping the mostly U.S. Marines hold off the invading force for sixteen days since Pearl Harbor had been attacked. Now they were all prisoners of war (POWs).

The Japanese and American cultures had different views about being a POW. Most of the Americans thought it was just bad luck that they had been captured, reinforcements would soon be along to right the problem. They had done a good job under the circumstances and were following orders when they surrendered. They felt no dishonor in being prisoners. Their attitude puzzled the Japanese as the Americans were actually able to make jokes about their situation and that of the Japanese. The Americans told the Japanese, who understood English, that they had better not stick around, that some American hospitality was on its way.

When the Japanese informed the Americans that Pearl Harbor and the American Navy docked there was in shambles and that Kwajalein, Guam and now Wake were occupied by the Japanese, the smiles gave way to looks of determination.

The Japanese on the other hand had been raised and trained that it was shameful to be made a prisoner. If you were taken a prisoner it suggested you had not done all you could in defending your post including giving one's life. Thus they could not understand the behavior of the captured Americans who were often smiling and telling jokes. This made the Japanese think even less of the Americans in their charge, had they no shame?

The next month, January, 1942, all the military prisoners and about 750 of the civilian were transported by ship to POW camps in China (occupied territory of the Japanese) and Japan. The civilian prisoners remaining on Wake Island were used to rebuild fortifications until September when all but 98 of them were taken to POW camps in China. The 98 were heavy equipment operators who were used to finish defense preparations. They were all executed by the Japanese in October, 1943.

Back in the States, Bernice Hansen of course knew of the events in the Pacific and she was desperate to know what had happened to her husband. A few days after Christmas she got that last letter that her husband, Peter, had written. It was dated December 4th and had the days Peter Hansen had remaining in the upper right of the page. He wrote I LOVE ALL OF YOU MORE THAN YOU COULD POSSIBLY IMAGINE (his capitalization). A line of Xs and Os were at the bottom of the letter. How Bernice Hansen must have felt, getting the letter, noting its date and contents while knowing Wake Island had fallen to the Japanese! It must have been a roller coaster of emotions. How to tell the children what had happened to their father?

It wasn't until three years later in January, 1944 that Bernice Hansen learned her husband had been captured and imprisoned at a POW camp in Fukuoka, Japan. She wrote him a brief post card thinking he might never see it. In April, 1944 Bernice got a post card back from Peter saying: Happy to have an opportunity to let you know I'm alive..... The post card showed her he was in Fukuoka Camp #1. She received another post card dated October, 1944 that had the closing statement Our happiness will be heavenly. Bernice received that letter on May 29th, 1945. Five months later she was notified by the U.S. Navy that her husband had died at the POW camp and that his body was cremated and placed in a memorial.

FAST FORWARD FIFTY FIVE YEARS TO JULY, 2000

A Mrs. Mary-Anne Stickney calls the Japanese Consulate in Houston, Texas and asks for their assistance. She explains that her mother, Bernice Hansen, is in her nineties and is dying. Before she goes, Mrs. Hansen wants to visit the gravesite of her husband, Peter Wales Hansen, who died at the POW camp in Fukuoka, Japan. Could the consulate assist in determining the location of the memorial mentioned in the Department of Navy notification of death.

The request is a first of a kind for the current staff at the consulate. Mrs. Chisato Tasai, to whom the call is routed, who is from Fukuoka, would normally have redirected Mrs. Stickney's call to U. S. government sources as all immediate post war activities and even later were controlled by the occupying United States Army under General Douglas McArthur. Instead she decides to ask Major Moran the consulate security officer if he will try to help the woman. Major Gerard P. Moran works for BP Security & Investigations, the some company that provides security at a number of other places in the Houston area. You will find BP Security & Investigation officers at City Hall, Jones Hall, the Wortham Center, the Houston Center for the Arts, Bayou Place, the George R. Brown Convention Center, some exclusive residential areas and Prairie View University to name a few of their locations. They have had a contract with the Japanese Consulate for more than a year. Major Moran had lived in Fukuoka, had served as an officer in the U. S. Army and had been a long time employee of a defense contractor to the U.S. Navy. To provide the best answer possible will probably require the assistance of someone familiar with the bureaucracy of the United States Department of Defense, the U.S. Army and Fukuoka. Major Moran could do this. He had also already demonstrated to the Japanese that he was a tenacious researcher and could probably field this question from the American caller.

Major Moran took all the information and promised Mr. Stickney he would do what he could to get her an answer. He cautioned her to not get her or her mother's hopes up as there were many factors that might make locating the memorial an impossible task

Immediately after the war, both sides worked hard to remove visible signs of the war from the sight of the population to effect a spirit of cooperation in the rebuilding of Japan. This and the fact that Mr. Hansen was a civilian and therefore probably not as well documented in official records as military prisoners may prove to be a problem.

Major Moran took to the internet to determine all he could about the POW camp in Fukuoka and to look for the U.S. government agencies that might be able to help him track information about civilian prisoners of WWII. The consulate assigned Mr. Ogawa to contact the Japan side of the equation to see if there would be anything in government archives about the location of the cemetery or a memorial for American prisoners of war in the Fukuoka POW camp.

Almost immediately, Major Moran was able to determine the task was going to be even more difficult than he had imagined. Fukuoka had multiple POW camps. Mrs. Hansen had been able to determine from her father's communications from Japan that he was held in Fukuoka POW Camp #1. Unfortunately, Major Moran learned that that camp had been moved three times in a ten month period from March of 1944 to January of 1945. He learned that last piece of information from Vincent Cooper, Head Teacher of an English language school in Kagoshima, Japan. This was confirmed with information from Marsha Coke of POW MedSearch. She offered descriptions of the POW camps in Japan for sale but said there were no rosters of POWs in the camps.

Mr. Cooper had logged a message on the internet stating who he was and that he was researching the experiences of POWs in wartime Japan and that he would focus on the camps in Fukuoka. Mr. Cooper had lived in Fukuoka before his move to Kagoshima. Major Moran asked for his help and asked for anything Mr. Cooper may already have found in his research that might help find the memorial.

Mr. Cooper's response to Major Moran's request was positive, but offered some details the family might never want to know. Besides informing Major Moran about the camp being moved three times, Mr. Cooper mentioned conditions appeared to have been brutal. There were unpunished public stoning of the prisoners and ghastly medical experiments carried out on some of them. Vincent Cooper concluded his message with the following:

I will be moving to this city (Fukuoka) at the beginning of next year and will of course try to locate the former camps. I do not currently know therefore if there is any memorial to the former POWs, though information I have received in regard to other camps both in and out of Japan would suggest that isn't likely. Former camps have been difficult to locate even by former occupants. The problem is compounded on the Japanese mainland by widespread lack of recognition of the war in most forms except the dropping of the atomic bombs.

The older generation simply don't pass information on and the younger generation are still taught history somewhat selectively.

Please feel free to keep in touch and I will let you know what I find in and around Fukuoka city.

In other searches on the internet, Major Moran came across different organizations with different pieces of the puzzle. He came across the American Consulate in Fukuoka web page during his research and requested their assistance in locating the memorial. Over the next several weeks he continued to garner information on Japan's treatment of American POWs, the siege of Wake Island, the construction projects on the island and information on Fukuoka POW camps.

He wasn't sure he wanted to share what he found with the Hansen family. American POWs in Germany suffered a death rate of approximately 4 percent, Americans POWs in the care of the Japanese had an astonishing 34 percent death rate! The medical experiments were done in Fukuoka and included dissecting U. S. prisoners while they were alive and without anesthetic.

U. S. government agencies which concerned POW affairs effectively told Major Moran that because of budgetary restrictions they were focusing their efforts on the Viet Nam years and to a slight degree on Korea that WWII issues were considered finished.

The U.S. and allied governments have not been particularly helpful to POW survivors or their families either in seeking compensation for the years lost. During the war, the Japanese held more than 140,000 Allied prisoners. Many of these Allied prisoners were forced to work long and hard under dangerous, unsafe conditions for Japanese companies. There has been little support over the years for the survivors in winning compensation from those companies from their governments.

The United States government right up to the Clinton Administration believe there are no reparations due from Japan over treatment of Americans they imprisoned during the war. They cite the San Francisco Treaty of 1951 which waived all reparations. In reality the government has not supported the claims of its people because, as was stated earlier, we were attempting to rebuild Japan in a spirit of cooperation. During the Cold War the U. S. government needed Japan in the fight against the spread of Communism most notably during the Korean War and then there were the ongoing negotiations for the keeping of U.S. bases in Japan

The POW survivors and their families are now turning to the court system for relief. In 1999 a class action suit was brought against the Japanese companies Mitsui, Mitsubishi and the Nippon Steel Company. In February, 2000 it was announced that Australian survivors of Japan's POW camps were suing Japanese mining, construction and manufacturing companies and in March, 2000 survivors of the infamous Bataan Death March filed a joint suit against five Japanese companies for slave labor.

A breakthrough in what was seen as the Allied governments intransigent behavior brought about by these lawsuits was seen by Major Moran when he noted an article reprinted from a May, 2000 Japanese newspaper (Asahi) stating that Prime Minister Obuchi had apologized to the Netherlands for the Government's "heartfelt remorse for the pain and hardship caused by Japan to many war victims, including Dutch people." Mr. Obuchi's remarks were an out growth of a lawsuit brought by Dutch survivors against Japan. The resulting thaw resulted in a monument being built in Fukuoka honoring the lives of the 869 Dutch POWs who died in Japanese hands.

Here was hope, maybe the line was now open to get more cooperation from the Japanese or American governments on where the Fukuoka POW Camp #1 memorial was located.

Almost a month passed before Mrs. Stickney called to ask Major Moran if he were able to find anything. Not wanting to share the gory details of what he had found and not wanting to admit he had nothing yet from either government side, the Major told Mrs, Stickney that these things take time to wind through the bureaucracy of two governments. He told her he did have some information but that it wasn't much and that he preferred to follow out some leads he had and to wait until he could give her what he had plus whatever Japan might deliver to Mr. Ogawa. "Please be patient" he said, these things take time. Mr. Ogawa confirmed that there was nothing from the Japan side yet.

An American professor of English at a Japanese university in Kyoto, Dr. Jason Goode, came through the Japanese Consulate in Houston for a visa to return to Japan for the next term. While he was in the consulate he and Major Moran got to talking. Major Moran told him of the Hansen's family plight and the difficulty he was having of getting pertinent information from Japan. It seems Dr. Goode used to work at the American Consulate in Fukuoka and he felt he still had some good contacts there. He volunteered to work on the project after he got back to Japan in about a week.

Mrs. Stickney called the consulate again in September. Major Moran told her of Professor Goode willingness to help and of Vincent Cooper's e-mail. He offered to share with her what else he had but that maybe she would rather wait on the response from Japan and get it all at once. She said no, she would like what he had now and would take what came later...later.

That night Major Moran did one more search over the internet. In one of his searches and knowing that Dutch and British POWs were at Fukuoka Camp #1, he decided to see what those queries would bring up. One of the things he found was that there was in the United Kingdom section of the Commonwealth war cemetery constructed in 1945 near Yokohama by the Australian War Graves Group an urn that was "recovered from two of the camps in the prisoner of war center at Fukuoka". It contained the ashes of 200 British POWs, 50 Americans and 20 Netherlanders. The names of those whose ashes were known to be contained in the urn are inscribed on the wall in a shrine in the British section. Another urn containing mostly American ashes recovered from Fukuoka was reported to have been sent to the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri.

The next day Major Moran duplicated all the information he had, composed a cover letter to Mrs. Stickney and sent it all to her. She was thrilled when she got the package. She read for the first time of the valiant resistance of the civilian contractors at Wake Island. She saw some of the details of where the Fukuoka Camp #1 was located at different times and read where people in Japan ( Vincent Cooper and Jason Goode) were going to help find her father's final resting place.

Mrs. Stickney took it from there and began following up on some of the leads in the material Major Moran had provided. She bought the description of Fukuoka Camp #1 from Mrs. Coke. Mrs. Coke told her of an organization, The Association of the Workers of Wake, Guam and Cavitie and gave her the name of the President of the organization. She sent off letters and e-mail to him and others.

Mrs. Stickney wrote a letter of thanks to Major Moran for his efforts and of the Japanese Consulate and sent along, as he had requested, copies of the letters and post cards sent from Japan by her Dad as well as the notification from the Navy of his death, a copy of the Description of Fukuoka Camp #1 she had gotten via e-mail from Mrs. Coke and a copy of a review of a book she had found on the internet by Gregory Urwin, Facing Fearful Odds: The Siege of Wake Island. She also sent along information about The Association of the Workers of Wake, Guam and Cavite as well as telling him about a "blue book" issued by Morrison Knudsen (the construction company doing the project on Wake Island and the other islands) with a listing of most of the people who worked on the projects and a picture of each.

A week and a half later on October 5th, Mrs. Stickney called Major Moran with the most amazing news. The letter she had shotgunned out to a number of people asking for help in locating her father's grave had gotten a more than hoped for response. A Mr. Randall Watkins with the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery e-mailed her to tell her that her father's ashes were among those received at the cemetery at the end of WWII. His e-mail read in part - "our records reflect that your father, Peter W. Hansen, is interred in Section 82, Grave 1B-1D...attached you will find two pictures of his headstone...." How Mary-Anne must have felt the moment she read that - happiness, sadness, relief and excitement knowing what she had to tell her mother. Mary-Anne had found her Dad and her mother's husband and he wasn't in a foreign country after all. He was right here in the United States. Mr. Watkins explained in his e-mail that Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis was selected as it was in the central United States and because the remains in the urn could not be identified and returned to individual families.

After fifty five years of not knowing for sure, Mary-Anne finally knew where her Dad was. The family made plans right away to visit the grave in St. Louis. Because there may be others out there who have suffered similarly, she wanted her story to be told and the names of the others known to be in that urn to be published in the hopes that someone reading this story will find the name of a lost Dad, husband, uncle, brother or friend that was so unexpectedly, so unfairly taken from their lives so long ago.

Here then are the names of the

others who died at Fukuoka Camp#1 and possibly other Fukuoka POW sites

were cremated and their remains placed in an urn that was sent to

Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri.

| Last Name | First Name | Date of Death | Service | Rank |

| Atkinson | John J | 2/24/1945 | US Army | LTC |

| Beall | John F. | 2/8/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Bell | William A. | 4/13/1945 | British Army | BDR |

| Bibee | Raymond E. | 2/19/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Bigot | Arthur | 11/26/1944 | Dutch Army | SLD |

| Black | Harry B. | 2/11/1945 | US Army | 2LT |

| Boers | Willem | 12/11/1944 | Dutch Army | SLD |

| Bonnett | Stuart B. | 3/11/1945 | British Army | BDR |

| Bovee | Frank W. | 2/18/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Brewer | Norman A. | 3/17/1945 | US Navy | ENS |

| Brooke | George M. | 2/28/1945 | US Navy | CDR |

| Brown | Paul A | 2/11/1945 | US Marine Corps | CAPT |

| Byers | Paul | 12/13/1944 | US Army | PFC |

| Callaway | Robert W. | 3/11/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Cogswell | Harold L. | 3/11/1945 | US Army | MAJ |

| Cross | I. J. | 2/24/1944 | British Army | GNR |

| Degooyer | Willem J. | 4/3/1945 | Dutch Army | SGT |

| Dickens | J. | 2/9/1945 | British Army | LBDR |

| Dillon | George O. | 12/23/1944 | Contractor | CIV |

| Duncan | Patrick H. | 2/25/1945 | US Army | 2LT |

| Dykes | Jack | 2/3/1945 | US Army | PFC |

| Espy | Cecil J. | 2/17/1945 | US Navy | LT |

| Evans | Martin M. | 3/28/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| French | H. G. | 12/18/1944 | British Army | LCPL |

| Gamble | John D. | 2/18/1945 | US Army | 2LT |

| Garama | Pieter A. | 9/27/1949 | Dutch Army | SGT |

| Gawler | A. W. | 12/25/1944 | British Army | GNR |

| Genung | Russell W. | 2/4/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Gibson | George H. | 3/31/1945 | British Army | SGT |

| Giesecke | Adolph H. | 2/6/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Gipson | Ernest P. | 1/16/1945 | US Army | CPL |

| Goldsmith | A. J. | 1/28/1945 | British Army | GNR |

| Goodpasture | Dexter D. | 12/11/1944 | Contractor | CIV |

| Goodwin | Ralph H. | 12/26/1944 | Contractor | CIV |

| Gottlieb | Henry | 1/13/1945 | Contractor | CIV |

| Hamilton | Donald W. | 2/3/1945 | US Navy | LTJG |

| Hamilton | George D. | 2/12/1945 | US Marine Corps | LTC |

| Hanenrat | Arda M. | 2/5/1945 | US Army | SGT |

| Hanes | Donald | 2/18/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Hansen | Peter W. | 3/21/1945 | Contractor | CIV |

| Hatch | Graham M. | 2/9/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Hawk | Floyd A. | 2/8/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Heath | A. | 1/1/1945 | British Army | GNR |

| Holloway-Cook | William T. | 2/25/1945 | US Army | LTC |

| Holm | Frits E. | 12/13/1944 | Dutch Army | SLD |

| Hormyak | John M. | 3/16/1945 | Contractor | CIV |

| Houseknecht | James E. | 3/29/1945 | US Army | PFC |

| Hurt | Marshall H. | 4/3/1945 | US Army | MAJ |

| Iacobucci | Joseph V. | 3/14/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Iversen | William C. | 3/31/1945 | US Marine Corp | PFC |

| Kellogg | Mont C. | 2/11/1945 | US Army | 1LT |

| Kelly | Sidney D. | 2/12/1945 | Contractor | CIV |

| Kennady | Marshall H. | 2/19/1945 | US Army | 2LT |

| Leitner | Henry D. | 2/17/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Lendewing | Lloyd T. | 3/3/1945 | Contractor | CIV |

| Leonard | William T. | 12/23/1944 | Australian Army | PTE |

| Lohman | Gordan W. | 1/24/1945 | US Navy | MM2 |

| Lyalle | Thomas A. | 1/22/1945 | British Army | GNR |

| Lyda | Fred G. | 2/16/1945 | US Army | 2LT |

| Lynch | James D. | 2/5/1945 | US Army | 2LT |

| Mareshal | Theodores J. | 1/12/1945 | Dutch Army | SGT |

| McKinzie | William J. | 3/16/1945 | US Army | 1LT |

| Mickelsen | Clayton H. | 2/4/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Mullaney | John D. | 2/3/1945 | US Army | 1LT |

| Murphy | Louis F. | 2/3/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Nicoll | J. S. | 1/26/1945 | Australian Army | PTE |

| Osborne | Lawrence E. | 12/19/1944 | British Army | SGT |

| Petty | John E. | 12/21/1944 | British Army | PTE |

| Peyton | Chester A. | 2/17/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Poirier | Dominique | 3/4/1945 | US Army | PFC |

| Preston | Everett R. | 4/21/1945 | US Army | 2LT |

| Schlingloff | Howard I. | 12/15/1944 | US Army | S/SGT |

| Scholes | Robert D. | 2/11/1945 | US Army | MAJ |

| Schrock | Murl R. | 2/4/1945 | US Army | 1LT |

| Search | Byron T. | 2/11/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Shiley | Earle M. | 2/2/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Smith | Phares P. | 12/27/1944 | US Army | PFC |

| Smyth | Thaddeus E. | 3/5/1945 | US Army | LTC |

| Solomons | Claas | 4/3/1945 | Dutch Army | SLD |

| Spickard | Thomas W. | 2/20/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Stalker | Leo H. | 1/21/1946 | US Marine Corp | PVT |

| Stookey | Wesley D. | 2/9/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Strong | Walter S. | 2/2/1945 | US Army | 1LT |

| Sult | Michael C. | 2/21/1945 | US Army | MAJ |

| Tacy | Lester J. | 2/9/1945 | US Army | LTC |

| Thomas | Frank C. | 3/19/1945 | US Army | 2LT |

| Thomas | William R. | 2/13/1945 | US Army | MAJ |

| Van De Water | Frans | 1/28/1944 | Dutch Army | SGT |

| Van Delden | Emile | 1/26/1945 | Dutch Army | SGT |

| Van Nouhuijs | Hermanus | 12/16/1944 | Dutch Army | SGT |

| Vedmore | Albert J. | 12/13/1944 | British Army | SPR |

| Ward | C. F. | 1/1/1945 | Australian Army | PTE |

| Warfel | Emmett A. | 2/16/1945 | US Army | CPL |

| Wiggins | George S. | 2/9/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

| Williams | Albert S. | 12/19/1944 | US Army | PVT |

| Wilson | Arthur H. | 2/27/1945 | British Army | GNR |

| Winall | Allan C. | 2/27/1945 | British Army | GNR |

| Worley | William J. | 2/27/1945 | Contractor | CIV |

| Wright | Harold B. | 2/8/1945 | US Army | CAPT |

September 20, 2000

Notes regarding efforts to obtaining information relative to final resting place of American POW Peter Hansen who died in Fukuoka Camp #1 during WWII -

Called Mrs. Stickney today, she had called the Consulate two days ago. I gave Jennifer the information to have Mr. Ogawa (who has queried the Japan side) return her call with an official response from the consulate relating to her original request in July. I called her today to see if she had gotten any response from the consulate. She said she has not heard a word. Mr. Ogawa is awaiting input from Japan.

I went ahead and shared with her what I had found and told her I would send it to her now or we could wait and see what the Japan side does as well as await some personal inquiries I had made from people in Japan. I read to her the e-mail from Vincent Cooper an English teacher in Kagoshima who was interested in the subject and offered to help. I told her that the camp had moved three times and that immediately after the war during the American Occupation that reminders of the war were quietly removed as a spirit of cooperation was emphasized. To this day there is a distinct reluctance for the Japanese to address these matters. All this combines to say there is not much chance in finding the memorial the family is looking for, or if it does exist much help in finding it.

On the other hand I told her of the Dutch memorial in Fukuoka which indicated the Japanese would respond to orchestrated efforts for assistance. I also informed her of my attempts to contact the assistance of the American Consulate in Fukuoka. I told her of Professor Jason Good who teaches English at Kyoto Gakuen University and his willingness to try to get some information for us when he returns to Kyoto next week. Professor Good used to work in the American Consulate in Fukuoka and feels he still has some contacts there that might prove useful. At the very least he can find out why we have not had a response from them. I also told her the U.S government is recalcitrant in responding to requests for information regarding WWII POWs. The agencies charged with POW questions is focused almost entirely on Vietnam and to a slight degree on Korea. WWII is considered a finished project.

Among the items I sent to Mrs. Stickney:

1. My memo to Jennifer (liaison to Mr. Ogawa) summarizing the request and what I had found.

2. A translation by Daniel King of two personal recollections of former Sub-Lieutenant Shigeyoshi Ozeki's who was among the Japanese who invaded Wake Island.

3. A review by Bill Stone of a book, Facing Fearful Odds: The Siege of Wake Island written by Gregory Urwin.

4. An Article entitled WAKE ISLAND DURING WWII from a war history website (http://www.goldtel.net/ddxa/war.html)

5. A book review by John M. Jennings of the Department of History, US Air Force Academy of a book written by an American POW in WWII, Andrew D. Carson, entitled Memoirs of an American Soldier Imprisoned by the Japanese in World War II. Mr. Carson was in a Fukuoka camp.

6. An article from the Tokyo Weekender entitled POW Plight, Allied WWII Prisoners of Japan Still Suffer by Milton Combs found on the website of the Center for Internee Rights (expows@ix.netcom) that refers to conditions at the Fukuoka camps.

7. An article from the Japanese newspaper ASAHI dated May 11, 2000 about the Dutch Memorial at Fukuoka.

8. A message posted on the internet by Vincent Cooper of vincepc@po2.synapse.ne.jp stating he is researching the experiences of POWs in wartime Japan.

9. Vincent's response to an e-mail from me asking if he could help locate the memorial in Fukuoka.

10. A picture of a Fukuoka Labor Camp from http://www.sfps.k12.nm.us/academy/bataan/laborm.html.

11. A page from the book, Courage Remembered, by Kinglsey Ward and Major Edwin Gibson found at http://collections.ic.gc.ca/courage/japanesecemeteries.html which notes that POW graves (actually ashes in urns) at Fukuoka POW camps were moved to two locations after the war - 1. Yuenchi Park in Hodogaya just north of Yokohama containing the ashes of 200 British, 50 Americans and 20 Netherlander POWS and 2. Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery St. Louis, Missouri which received the ashes of mostly American POWs (there were others from other countries mixed in).

12. A response from Marsha Coke, Chair Person of POW MedSearch (http://www.ax-pow.com/med_srch.htm) when I asked her in an e-mail if the descriptions of POW camps she was offering for sale would answer Mrs. Stickney's questions.

Mrs. Stickney also gave me a few items of interest: She told me that she had also done some searching on the internet and had bought the Description of Fukuoka Camp #1 from Marsha Coke, Chair Person of the POW MedSearch at http://www.ax-pow.com. She said she would make me a copy and send it to me. She also agreed to send copies of the v-mail the family got from Mr. Hansen. I asked her to send them to my home address (quicker).

There is a POW survivor of Camp #1 a Mr. Ben Comstock of Nebraska. He is represented as an expert on the subject of Camp #1. She has his cell phone number and planned to call him today. She got his name from Marsha Coke. Her father was 40 when he was captured. He died on March 21, 1945.

I sent an e-mail to Vincent Cooper telling him all the facts in hopes he will make a visit to Fukuoka and telling him if he finds anything relevant to contact Mrs. Stickney directly. I provided him her address.

September 26, 2000

Mrs. Stickney called today to say she had sent me the materials promised and had received the ones I sent her and was grateful. She also said that she had found an organization called the Association of Civilian Internees of Wake, Guam and Cavite Island. She said they had 130 members and that she was going to pay the $10.00 annual fee to see if any of the members knows anything of her father or Fukuoka Camp #1. She provided the name and address of the President:

Mr. Chalas Loveland

9517 Caraway Drive

Boise, Idaho 83704

I briefed Jennifer and told her Mrs. Stickney seemed pleased with what we had provided her and was now set to go off on her own investigation following up on leads gleamed from the materials I had provided and the internet.

Received the package from Mrs. Stickney. In it was a letter from Mrs. Stickney listing the contents:

more details on Workers of Wake, Guam and Cavite

info on a "blue book" given to all returning ex-POWs employed by Morrison Knudsen of Boise, Idaho which lists most of its employees plus a picture.

Mrs. Stickney mentions a Lee W. Wilcox who was not listed but was with her father.

Letter from P.W. Hansen from Fukuoka

Post card from P.W. Hansen from Fukuoka

Copy of a post card to P.W. Hansen from Beatrice Hansen

Letter from P.W. Hansen on Wake

Letter from U.S. Navy notifying Mrs. Hansen of death of P.W. Hansen in Feb., 1945.

Letter to U.S. Navy from Mrs. Hansen asking them to change date of death to reflect information from returnees.

Letter from U.S. Navy agreeing to the change

Description of Fukuoka Camp #1

Item from web page at http://vikingphoenix.com/public/ronstadt/military/pow/pwcmps-2.htm about Japanese POW war camps

October 4, 2000

I am pleased to report a happy ending to the effort to assist Mrs. Hansen and Mrs. Stickney in locating the final resting place of their husband/father, Peter Wales Hansen.

Mrs. Stickney called me at the consulate this morning to say she had sent a letter to the cemetery at Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis, Missouri and that they had sent an e-mail back saying that, indeed!, her father was buried at their cemetery and even included a picture of the grave. Mrs. Stickney cried while she told me how she called to share the news with her mother, brother and sister and that after 55 years their family finally has some sort of closure over the loss of their father/husband. The family is making plans to visit the grave in the near future.

She asked me to thank Vincent Cooper for his help and to provide him with Mr. Loveland's address and her own E-mail address, edmastic@flash.net and to thank Professor Goode for his efforts on her behalf.

She profusely thanked me for my help asking at the end of the conversation why I had included the cemetery data in the packet I sent her. I told her I had guessed the Japanese had cleared out all the POW graves in the Fukuoka area and moved them to either or both locations specified in the article and that it was a possible lead that could be followed up on.

I told Mr. Ogawa the news and he told me that he had gotten word back from Japan that there was no available information from Japanese records of the location of American POW remains in Fukuoka. There were records of what Japanese were assigned to the camps and of the camp daily operations. There were no references to individual Americans. He was glad Mrs. Hansen and her family were able to find a resolution to their search.

Knowing that there were others out there whose father/brother/husband died in Japanese POW camps and were never told of their loved one's final resting place, I decided to place a call to Houston Chronicle writer Bob Tutt, who I remembered did historical feature stories, and ask him to call Mrs. Stickney and get the skinny on a great story. He wasn't there when I called, so I just left Mrs. Stickney's name and number for him to call for a good story.

Just in case, started writing the story myself which I may submit around here and there if the Chronicle does not pick it up.

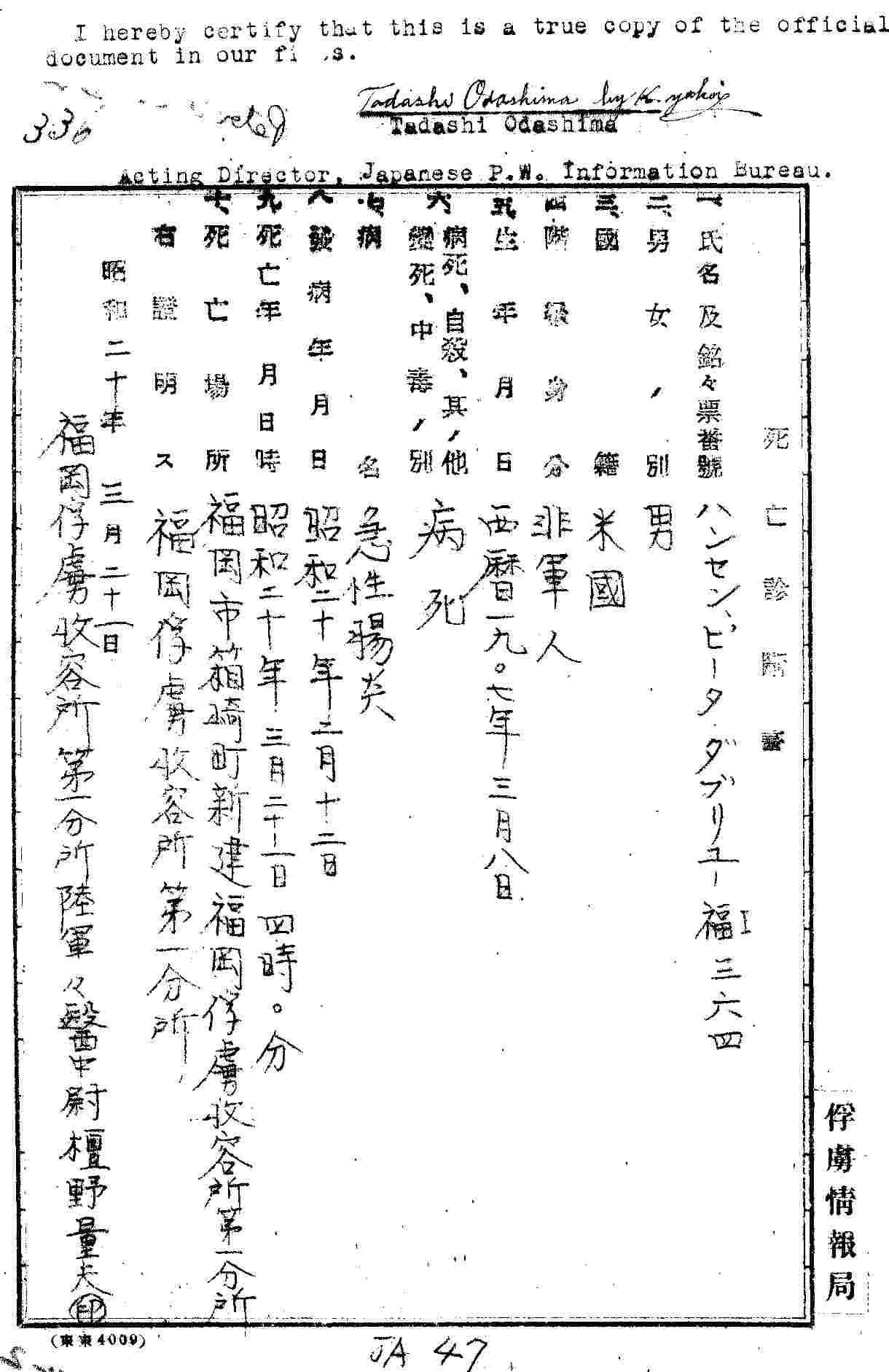

Death Certificate for Peter W. Hansen

|

INDIVIDUAL RECORD CARD 1. CAMP: FUKUOKA, 13 October 1942 10 Oct 1943 - Transferred jurisdiction from

Sasebo Naval Station and interned I hereby certify that this is a true translation of the official record in our files. (signed)

DEATH CERTIFICATE 1. Name and Individual Record Card No.: HANSEN,

Peter W., FUKUOKA 1B - No.364 Aforementioned is certified: 21 March 1945 Volume No. JA 47 - 336 I hereby certify that this is a true translation of the official document in our files. (signed) |

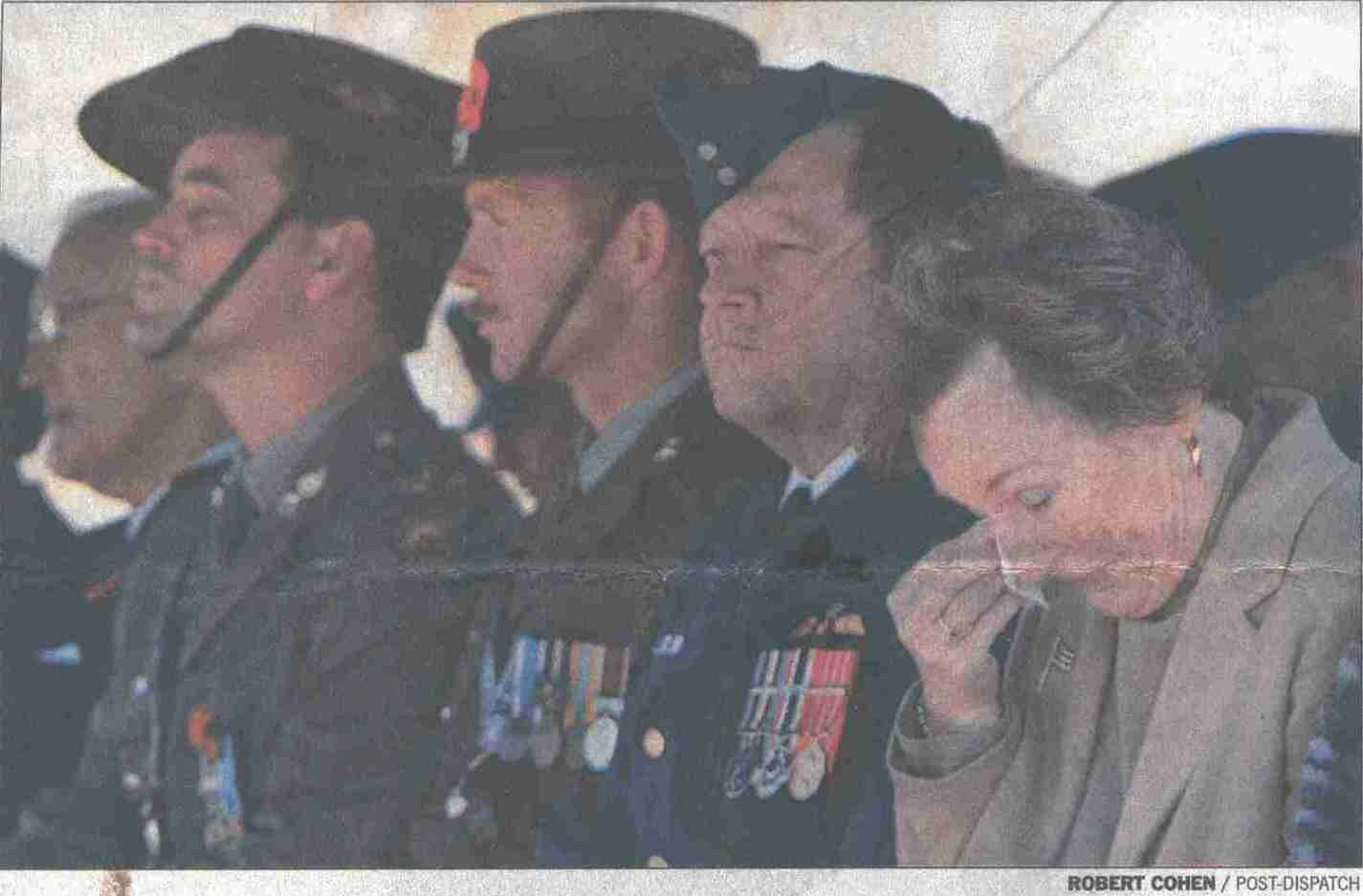

ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH

METRO ST. LOUIS

Tuesday, November 12, 2002

REMEMBERING

Mary-Anne Stickney grieves

at Monday's Veterans Day ceremony at Jefferson Barracks National

Cemetery. Stickney, of Houston, attended the ceremony honoring 100

soldiers and civilians who died in a Japanese prison camp in World War

II. Her father, Peter Hansen, who had been a civilian contractor, was

among them. With her are members of allied military staff stationed

here.

Mary-Anne Stickney grieves

at Monday's Veterans Day ceremony at Jefferson Barracks National

Cemetery. Stickney, of Houston, attended the ceremony honoring 100

soldiers and civilians who died in a Japanese prison camp in World War

II. Her father, Peter Hansen, who had been a civilian contractor, was

among them. With her are members of allied military staff stationed

here.

Texas woman attends

service here to gain closure over loss of father

He died in a Japanese prison camp in WWII

BY MICHELE MUNZ

Of the Post-Dispatch

Mary-Anne Stickney, 68, has been seeking closure since she was 10 and learned that her father was dead.

The woman from Houston was hoping she would finally find it on Veterans Day at a ceremony at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery that honored 100 soldiers and civilians who died in a Japanese prison camp during World War IL

"We never had a memorial service for my father," she said Monday, as veterans were being honored across the country. "We just got a telegram saying he died. That was it. There was no closure."

Stickney was 6 when her father, Peter Hansen, went to Wake Island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean -- about halfway between Japan and Hawaii -- to work on a construction project for the Navy. He went there in March of 1941 and had a ticket home for Dec. 23. But on Dec. 7, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Soon after, they attacked Wake, too.

On the day Hansen was supposed to fly home, he was taken into captivity along with about 1,500 other Americans, most of them civilians like him.

Hansen was taken to a prison camp in Fukuoka, Japan, and was able to send his family a few postcards. But in October 1945, the Hansen family was notified that he had died, and that his body had been cremated and placed in a memorial in Japan.

Two years ago, Stickney tried to find this memorial. She wanted to visit it with her mother, Bernice Hansen, who is 92. She contacted the Japanese Consulate in Houston and asked for help in locating it.

Her request was forwarded to Maj. Gerard Moran, who after an exhaustive search, learned of two urns containing the ashes of prisoners held in Fukuoka camps. One urn had been sent to a war cemetery near Yokohama, and another containing mostly remains of Americans had been sent to Jefferson Barracks because of its central location.

Stickney contacted Jefferson Barracks to see if her father could be there. An employee, Randy Watkins, found Hansen's name on the tombstone marking the mass grave site. Watkins took two pictures -- one of the stone and one of just the name -- and e-mailed them to Stickney.

Seeing her father's name brought Stickney to tears. "That proved to me that he was really a person that walked on this earth, that he isn't just a memory," she said. "We know where he is now, and that means a lot to me."

Stickney visited the cemetery in November 2000. She said she felt as if she was 10 again and had just learned of her father's death. But this time, she cried -- a lot, she said.

She still didn't have closure, though. She thought it would come Monday when she attended a Remembrance Day ceremony at the mass grave site with her sister, Luci Hansen, 71, of Vista, Calif., and her brother, John Hansen, 69, of Tucson, Ariz.

In recent years, members of military staff from allied countries who are stationed at Fort Leonard Wood and Scott Air Force Base have joined the Australian, British and Netherlands consuls in St. Louis in holding an annual ceremony at the grave site. The common grave includes the remains of 71 American servicemen and civilians and 29 Dutch, Australian and British soldiers. A representative from each country places a wreath on the tombstone as part of the ceremony. This year, Stickney and her family placed a wreath as well.

"I thought maybe this would be closure, to have a real ceremony, especially with my brother and sister here," she said. "But I don't think I'll ever have closure. There's just an empty hole in my life."

The ceremony's speaker, British Col. William Bailey, told the crowd of about 50 that not one prisoner of war who suffered in captivity would question whether the sacrifice was worth it if it preserved the freedom and lives of loved ones.

In Veterans Day ceremonies across

the area, others spoke of the importance of honoring those who gave

their lives:

-

In St. Peters, Missouri Sen.-elect Jim Talent spoke at the Veterans Memorial, where 37 veterans of D-Day were honored with commemorative medals from the state.

-

In Hillsboro, Navy Lt. Terri Schrader told a group of Jefferson County veterans: "All Americans need to have an understanding of the sacrifices of the past to give you and I the freedom to make the choices that we have today."

Reporter Michele Munz:

E-mail: mmunz@post-dispatch.com

Phone: 314-340-8263

Medals Posthumously Awarded to Peter Hansen

On July 30, 2010, Peter Hansen was posthumously awarded the following medals:- Purple Heart

- Marine Corps Expeditionary Medal with Silver "W" for service on Wake Island

- Prisoner of War Medal

- World War II Victory Medal

- American Campaign Medal - WW II

- Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal - WWII

For information on how to obtain medals for ex-POWs and civilian internees, see Search Helps.

|

Excellent site on the

Marines defense of Wake, with photos of some of the men Hansen knew:

A

Magnificent Fight: Marines in the Battle for Wake Island For a very good background on the Marines and contractors on Wake Island (with many pages about Hansen), read Building for War - The Epic Saga of the Civilian Contractors and Marines of Wake Island in WWII by Bonita Gilbert (2012). |