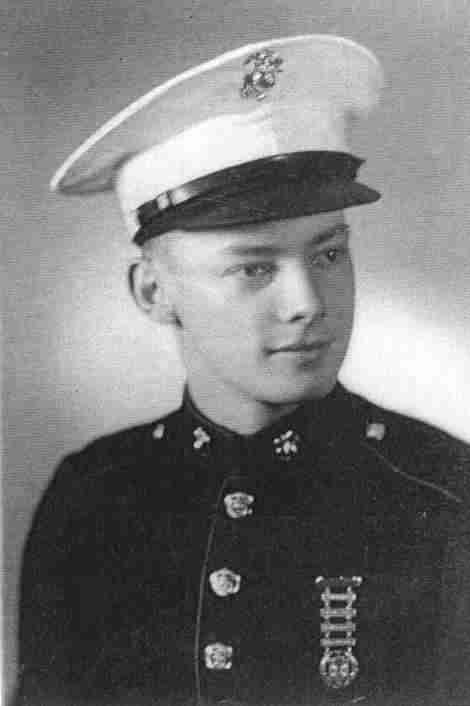

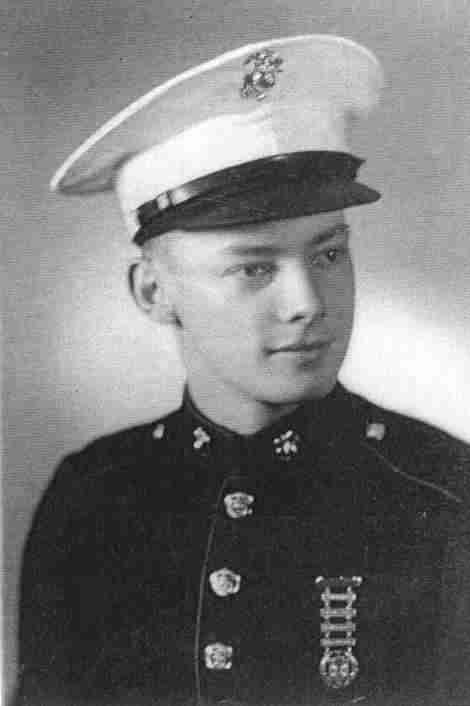

DONALD L. VERSAW, born June 23, 1921 in Bloomington Nebraska. Joined

the U.S. Marine Corps on Armistice Day, 1939 in Chicago. Following recruit

training and a short term with the Marine Corps Operating Base Band, San

Diego, CA he was sent to Shanghai, China for duty with the 4th Marines Band.

After the regiment was evacuated to the Philippines and at the outset of

World War II he became an infantryman in E Co. Second Battalion, Fourth Regiment.

When Corregidor was surrendered to the Japanese in May 1942, he spent the

next 40 months as a POW in the PI's and in Japan.

During captivity he was held on Luzon Island mostly at on work camp near

Clark Air Base for more than two years. In July 1944 he was moved to Japan

in one of the notorious "Hell Ships" - (unmarked freighter/troop ships) -

and put to forced labor in Nittetsu-Futase Tonko Kaisha (coal mine company)

on the Japanese island of Kyushu. This company paid enlisted men 5 sen per

day for their labor. [(A sen is one one hundredth of a yen)(One yen was then

equal to ten American cents)] Deductions were made at the rate of 50% deposited

in Japanese Postal Savings Plan.

Following repatriation, he remained in the Corps and married Amelda Gilmore,

a union that has lasted more than 52 years ending in her death in October

of 1999. They had two daughters, Judith and Denise. In 1950-51 he served

in Korea with the 1st Marine Division in a Photo unit. After retirement in

1959 he worked in the aerospace industry for 13 years on the Saturn and Apollo

programs. He completed 10 years of Civil service divided equally between

the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Air Force; he retired in 1984

with a total of 31 years federal service. He is a Life member of American

Ex-POWs and served two years as a Chapter Commander and it's Treasurer for

a number of years. He is a life member of the American Defenders Bataan and

Corregidor, the Disabled American Veterans, American Ex-Prisoners of War.

He is a member of the American Legion Post 142 Bloomington, Nebraska, the

China Marine Association and Marine Corps Musicians Association.

Website: THE

LAST CHINA BAND

For more information on Marine POWs, visit this very informatimve page:

Appendix A,

Marine POWs

Excerpts from

Mikado no Kyaku

by Donald Versaw

POW at Futase Camp #7

(formerly Camp #10-D)

Dedication

To the thousands of Allied soldiers, sailors and airmen who fought and

died that many millions of us would enjoy freedom again.

and

To all the Filipino people who put themselves in harms way to help the

plight of American prisoners of war in so many ways.

and

To the few Japanese soldiers who occasionally showed great compassion

to their captives along with the millions of civilians who had to suffer

and die needlessly for all the wrong reasons.

PREFACE

This book is the story of having been a prisoner of war of the Japanese during

most of World War II. A great many people -- thousands of them -- endured

an almost identical trial in their young lives as I did. A number of us have

written books about it and now, in the fading light of our lives, more are

doing so. Most have published their work at their own expense. This book

is another example.

Not unlike many other offerings, this one was originally titled "Guest of

the Emperor." It may have been one of the very first manuscripts to bear

that title, the first draft having been typed during the winter of 1945.

Some years later, a heavily edited version was hand-published on a Multilith

by Arlene Brown and Bill Holly, and a number of Accro fastened copies were

run off and given a limited distribution. The editor of that edition was

Ruth Reynolds, a professional writer of crime stories for the New York Sunday

News.

Early in 1990, Noel and Norma Roberts, both avid readers, became interested

in the Reynolds' edited manuscript. They felt the story really prompted more

questions than it answered and left them wanting to know more about my experience

and in greater detail. I set about doing this. They gave me great assistance

with editing and encouragement.

I

was not yet 21 years old when the island fortress of Corregidor was surrendered

to the Japanese. I spent my 21st, 22nd, 23rd and 24th birthdays in captivity,

but the only birthday I was ever allowed to celebrate was that of Emperor

Hirohito each 28th of April. The observance was marked by extra long hours

at hard labor. I

was not yet 21 years old when the island fortress of Corregidor was surrendered

to the Japanese. I spent my 21st, 22nd, 23rd and 24th birthdays in captivity,

but the only birthday I was ever allowed to celebrate was that of Emperor

Hirohito each 28th of April. The observance was marked by extra long hours

at hard labor.

If nothing else, this will serve as a historical record for my descendants,

family members and friends who may have an interest in knowing what happened

to me in the Philippines and in the land of the rising sun so many years

ago.

I have struggled a long time with a title for my work. It is still "Guest

of the Emperor" to me and will remain so, but in Japanese -- Mikado no Kyaku,

was a phrase used by Japanese officials in the prison camps, where we were

often cruelly reminded that was what we then were, "guests". They were hosts

of a kind so cruel as at times to be beyond definition. It is only in recent

years that citizens of Japan have learned how their wartime government grossly

abused thousands of their captives. This story is an account of a luckier

one than many.

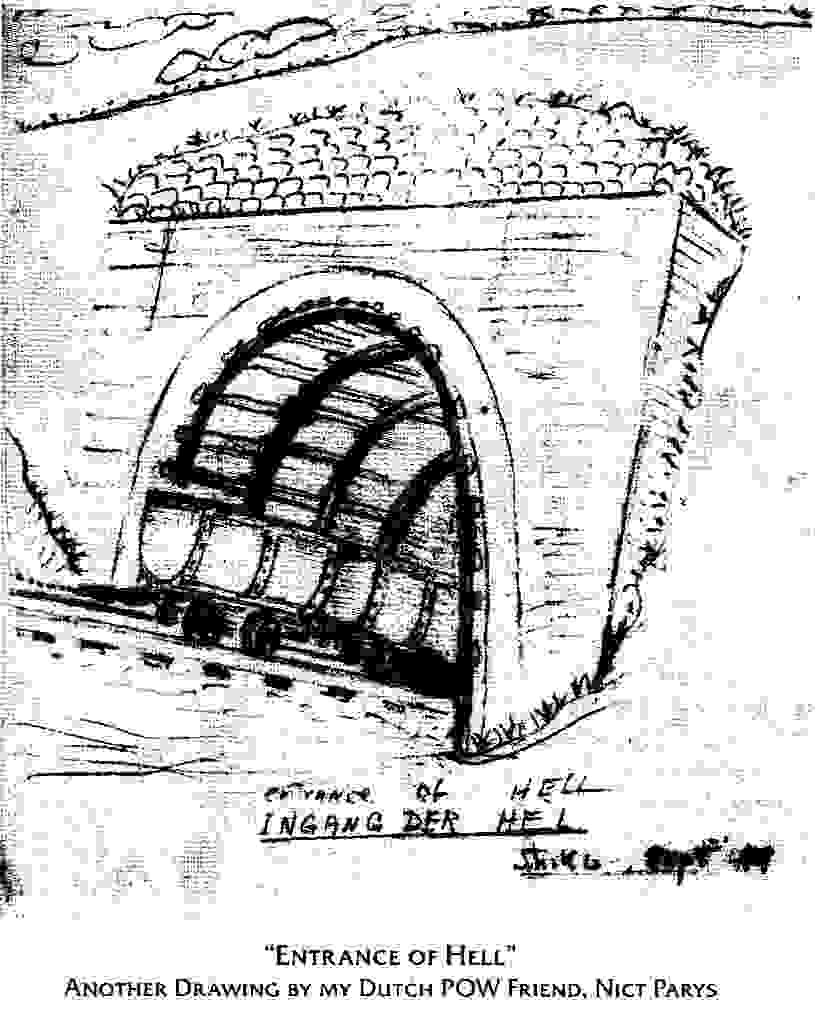

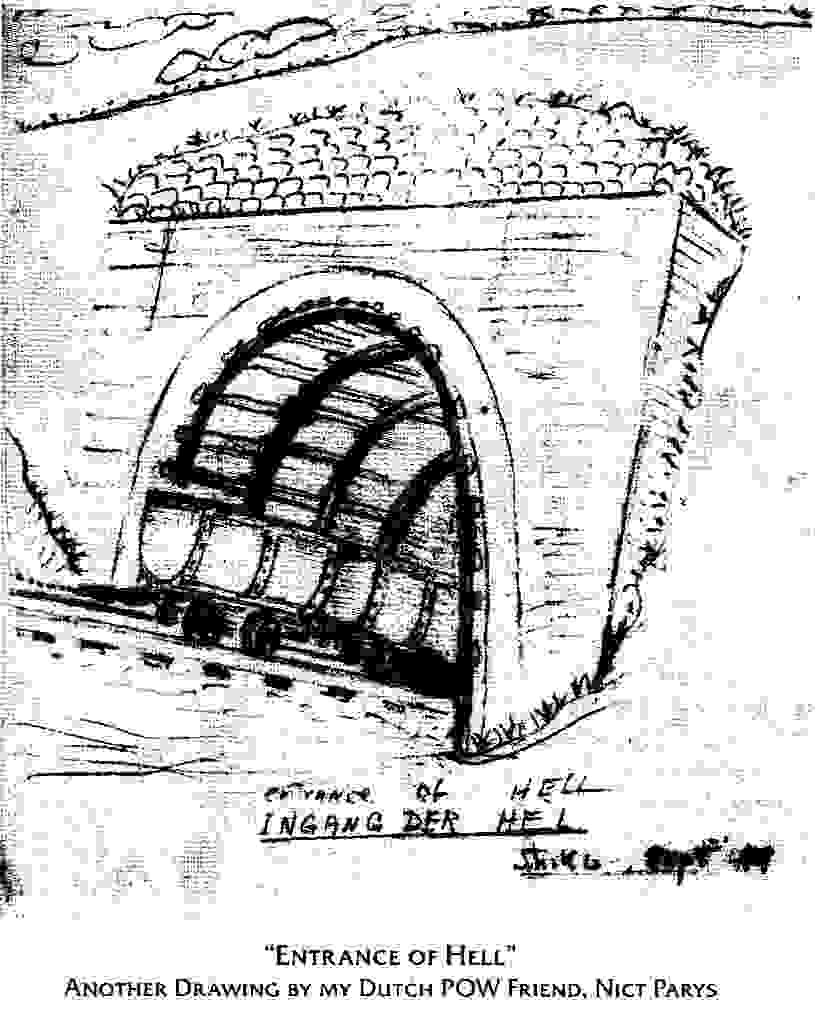

My saga begins where the experience ended. Enslaved at work in the Kyushu

mines, having survived more that two years of confinement in Luzon, Philippine

Island prison camps and following a terrifying and horrific voyage at sea

in a ship of Hell from Manila to Moji, Japan. I was made to work for food

in a coal mine. In Japan they are dark, dank and fearful places. The only

thing to help relieve the terror was to focus on the moment and try not to

worry about cave-ins, brutal beatings, the pangs of hunger or the hell of

tomorrow. This is the condition of the whole matter of being a prisoner of

war. You can't wonder if you will ever see the light of day again, if you

will ever taste the sweet joy of freedom. You must know that you will, simply

because there is a merciful God in heaven in whom you trust all things.

dlv / 1998

Chapter Six

The Nissyo Maru -- A True Trip of Terror

After a light breakfast, which was nothing more than a tiny ball of sticky

rice, the big gates of the old prison opened and we marched out into the

nearly deserted city street. I was surprised how near it seemed we were from

the Manila docks, for we were soon there, standing in ranks. In the distance,

we could see Corregidor -- that little black bump on the horizon to which

MacArthur had not yet returned. Another large group of prisoners from the

Port Area work party was waiting for us. Together in the two groups there

were about igloo of us ragged looking, strangely clad, bone thin, weary warriors

-- already survivors.

There were many among us that had no idea of what we faced in the mottled,

rusty-red transport that's moored to the dock in front of us: the Japanese

ship Nissyo Maru. It looked as though it could accommodate no more than half

of us. We stood most of the morning in the dock house. The Japanese guard

came to us one by one. They asked if we had any knives, matches or pencils;

then, made us open any packages, quan bags and the clothes we were wearing

to see if we had any of those items. Those prisoners who were found to be

carrying cigarette lighters, scissors or razors were beaten on the spot and

the stuff confiscated.

In a long single line we then marched over the gangplank, stretched up and

over the brown oily waters in a hell ship. I could see some commotion on

the deck ahead. I came to a gamut of Japanese soldier guards and recognized

one of them as the notorious "Mickey Mouse" From Military Prison Camp 1.

He was given that name because of his huge ears and mousey-like personality.

He knew and could speak a little English and was curious why he was called

Mickey Mouse. When told that it was because he was a lot like a famous American

motion picture star, he accepted his "handle" gratefully. But, Mouse was

not grateful this day. Rather he was shouting like crazy, "Take off shoes!

Throw in hold! Hyyaku! (hurry) All bags too! Now! Go down ladder, speedo!

speedo!" He punctuated his urging with shoves and pushes with his rifle butt.

The men he struck pushed those ahead and terror struck others close by as

they hurried to get into the hold on to ladders as bags and boots bounced

off heads and backs of the hapless men trying to get out of the way. We moved

on as others poured onto the deck behind us to receive the same brutal welcome.

The orders were repeated in staccato. "Air Raid", another even more notorious

Camp 1 guard joined the Mouse at pushing, shoving, and hitting the men scrambling

to come on to the ship and into the hold.

Subhuman Cargo...

My shock had little to do with the roughness even though I had no idea this

was the standard method for loading a Japanese vessel with its "subhuman"

cargo. I was more concerned as I scrambled down the ladder to find the hold

was already crammed full, as far as I could see, with half naked, sweating

men in ragged, beige-colored tatters. The quan bags and footgear had already

become a pile twice the height of a man. Nearly 700 men had already entered

the hold before me. Behind was another 800 more to come. There couldn't be

room for their baggage, much less the men. But our captors kept shaking us

down, like one shakes down the garbage in a bag to make room for more. And

that's what we were to them -- garbage. I was pushed back away from the opening

of the hold. My eyes became accustomed to the half light; under the covered

part of the compartment, I could see wooden tiers for sleeping. They stood

one above the other, five or six feet high, with an 18 inch clearance for

each, like cages for animals in a pet shop. I wedged myself into one of the

slots. It was very close even for a little fellow of five feet and six inches,

like myself. I found I couldn't so much as raise my elbow and, with more

and more men crowding in, there was no escape, no way to back out. I was

trapped. It was apparent the guards intended each box in the array made for

one person to hold five or more prisoners. I could hear them counting.

Others squeezed in to escape the rain of shoes and stuff still coming down

like hail from above. The racket from the yelling and shouting was deafening

back in the slots. I tried to listen and make some sense of it over the racket.

"Oops...What's the matter...He's fainted..." That was just the beginning.

As the newcomers jammed into the hold, those who had been there 40 minutes,

30 minutes, 20 minutes began to drop. Well, rather they slumped in their

faint. There was no room to fall. Those who still had their wits about them

in all that bedlam, sought to push the weak back up to the deck; a thinner

outgoing stream of limp humanity met a forceful incoming flood of men leaping

downward away from the frantic gamut above. "Air Raid" frantically tried

to wear himself out beating at the flow of prisoners trying to move in both

directions. He seemed to be inexhaustible. Obviously, he thought, some of

the limp were pretending. Maybe some of them were faking unconsciousness;

most were not and none was not terrified.

As others reached the fresh air above and were revived, they were redriven

back down into an already fully packed mass of flesh and piles of stuff below.

The once cool morning had now become a blazing midday inferno as the tropical

sun in a cloudless, July sky bore down on the steaming scene of misery in

Manila. The old, rusty, converted collier absorbed the scorching heat; it

was like being on the inside of a giant steam iron. We cooked and I felt

myself being pushed deeper into the sleeping slot, farther and farther away

from the air and the light of the opening. The bedlam subsided to a hum in

my ears: the hold turned gray. Without orders from the captors, a few brave

and desperate men snatched up the hatch covers from beneath them and began

tumbling the baggage into the hold below. Doing so made a little more room

for those still stumbling down the ladders, but offered little relief for

those already crammed into the space not larger than half a tennis court.

Even the most ignorant Japanese guard must have known it would be an

impossibility to stuff all igloo of us into such a small hold. They tried

their damnedest, nonetheless. Outside my crevice-like slot, men were still

slumping. We who were motionless and not struggling were still soaked with

sweat -- our own and that of our fellows. Water dripped on me from the slots

above. I thought at first some poor duffer's kidneys had failed him or that

a canteen had broken open. Perhaps so, but most of it was sweat. I sweat!

And the stench! God! The stench! "We must have more space! More space! It

would be better that we be shot now! We must have more space."

It could have been hours -- maybe it was only a few minutes -- for the American

interpreter to convince the Japanese that 1,500 men couldn't be jammed in

such a small, hot space and expect them to live very long. But it took long,

tortuous hours for our hosts to do something about it. After sundown, the

guards yelled down for all men whose numbers were below 700 to climb out

and go to the forward hold of the ship. Such a scrambling over each other,

and under each other! Finally those left behind found themselves with a little

more space; it was precious little. It did make breathing a little easier.

Those that went forward tried to scoop up lungs full of cooler evening air

before going down the ladders into the slightly larger hold. Again, the guards

urged every one along with little less frantic intensity even though they

had been at it for hours and hours.

I was among those moved forward. There were no sleeping bays, just solid

iron decks surrounding another hatch, covered with huge planks fitted with

metal bands and hand-holds, directly beneath the opening overhead. It seemed

larger on that account and probably was; there still was not room for all

to sit at one time upon the hard decking still warm from the blistering heat

of the day. To have enough space to lie down and stretch out was out of the

question.

Out of Control...

The noise from all of us yelling and screaming just never stopped. Everything

was out of control. Officers and others who tried to get the group to quiet

down and organize things were shouted down. Men who tried to claim a bit

of space to stand or sit were shoved about in all directions. "This is my

spot!" one would proclaim of a square not much larger than his two feet.

"The hell it is!" an offended neighbor would yell back as loud as he could.

But the sound of his voice could not be heard five feet away as it would

be drowned out by the yelling there. Men in one quadrant of the hold would

find themselves in the one opposite without having made any effort to move

at all. The mass of flesh just seethed around like so many beans in a boiling

pot. It was sheer bedlam and pandemonium all through the night. Little by

little a tiny bit of order emerged. The few older officers, some of them

doctors and chaplains, managed a little control. It was very difficult for

them. Chaplain Stanley Reilley's effort is memorable and heroic. He

made himself heard and it helped, but there were others who tried.

The following day, enough water was lowered down to us by selected prisoner

helpers up on deck so that each man got about a half pint on two occasions.

A bigger problem was what to do once it ran through one's system. There were

no convenient latrines at all, not until a large wooden tub was lowered on

ropes to become our night chamber. It was quickly filled and sometimes overflowed

before being drawn above and disposed of over the side of the ship as a growing

long line formed around the perimeter of the hold to wait its return. It

made a mess around the tub that is beyond description. Those unfortunate

souls near it pressed hard against their neighbors to get away from it. The

line never ended and stood for the entire seventeen days we spent aboard

the Nissyo. The tub was hauled up, emptied and lowered down again, each half

hour, 1000 times or more. Some Medical corpsman were detailed to handle the

nasty chore in round the clock shifts. There was no shortage of volunteers

for the job however, because of the opportunity to be on deck in the fresh

air, and out of the teeming, hot mass of sweating bodies below. It was a

necessary but filthy mess, particularly for those in the vicinity of the

operation. Because of the motion of the ship these prisoners were subject

to many unfortunate accidents. A few latrines were available up on deck built

out beyond the gunnels, but only a lucky few were able to ever use them once

they managed to get topside.

It was a great relief to the men huddled so tightly together in the ship

when, after another long, hot day, the ship moved away from the dock. The

throb of the engine could be felt as the decks and bulkheads creaked and

vibrated. But all shuddered with it. The sooner things happened, the sooner

we could get off this terrible vessel. Then, after a short time, we shivered

with despair for we heard the anchor chain rattle out of its locker as it

was dropped. We soon knew we were standing just a few miles from Corregidor.

There the ship sat and sat -- and sat -- for four, whole. hot, sizzling days

while we stood and slumped against each other watching the yellow bucket

running up and down regularly to and from topside. Our beards growing bristly

for lack of razors and water to cut them. The rumor was that our ship was

waiting for the formation of a convoy. Men began to work out ways for some

to sit a while. In my turns I, fitfully, slept a little. This was complicated

by some space ruled off for a "sick bay". In this space, those who were

determined to be sick were allowed to stretch out and lie down. This made

it ever more crowded for the others. There was some compassion for those

still worse off than others -- it was not a lot. Small quantities of steamed

barley were lowered to us twice each day along with the little bit of drinking

water -- a half pint for each and it was not enough. Men became desperate

for water and attempted to trade their little ration of food for water. Those

who were too dry to eat soon found someone too hungry to eat. A strange thing

occurred. The "dog eat dog" attitude so prevalent within the camps seemed

to disappear in this awful, seething mass of men. "Here, Joe, you need it

worse that I need it..." was sometimes heard. I saw trembling hands of one

shove canteens into another's ghost-white lips.

We heard the anchor being pulled up and the ship moved again. I wish we could

say we felt a little breeze coming through from above. The men all joined

in a great deafening cheer which grew louder, ultimately growing into a roar

-- like a capacity crowd at a championship football game as the favorites

come trotting onto the field. There was no place for the sound to go so it

came right back at us. God knows why we were cheering, just the encouraging

thought and hope that our terror and desolation would end soon. Any change

seemed welcome. Had we known what was to happen to the Oroyoku Maru, the

Brazil Maru and the other hell ships that tried to come after us, and were

even more terrifying and sunk with great loss of life, we would not likely

have done so. Again, going on to anywhere was preferred to just laying-to,

broiling in the sun. Whatever it was we talked, we shouted, and our ears

rang with the sound of our own voices; the confusion went on all night. The

Japanese guards wearied of it and told us to shut up or they would shoot,

but we didn't and they didn't. You could tell by the roll of the ship that

we were out of the bay; out of sight of the black rock of Corregidor that

had once been our sanctuary and lost hope of victory. Out into the great,

blue, South China Sea. We could only imagine what it looked like and where

we were headed -- God only knew where.

Now, as men seem always to do, we tried to build ourselves communities. A

few of the inventive made hammocks in the overhead. Others staked out imaginary

claims on sitting space. Since there wasn't nearly enough to go around, there

were always arguments as to whose posterior was covering whose spot. The

men with the larger behinds caught the most hell. There were even some fights.

Not because anybody was really angry but, just because emotions had bulged

up like balloons, too full of air. They had to burst. After a fight, everybody

would sit quietly for a while and then "Hey, you, son of a bitch, who the

hell..." "Who's calling me a..." And another fight would begin. The ship

plowed on and on through smooth seas, rough seas, choppy seas. The sun rose

and the light came through the hatchway and zigzagged wildly around our pen

as the ship followed a defensive course to avoid our American submarines.

The sun set.

The noise, the din and stench went on all night. We watched the heavens through

the hatchway and tried to make them out. But, they skewed across the deep

blue-black field like shooting stars, first in one direction and then, as

the ship turned, scooted back again. Watching them kept your mind off the

possibility of a raging torpedo smashing into the thin hull of the old ship

and blowing us into kingdom come. The sun rose and there was light again.

I thought of the times that tourists had paid hundreds of dollars to take

this very trip from Manila to Japan in luxury and comfort. The food situation

was not ideal, but we had all been in worse situations. Cooked barley, sometimes

with a little rice, was lowered on ropes in the same kind of buckets used

to lift out the waste. We hoped they were different ones. Each bucket was

intended to feed 150 men, according to numbers. Control was just impossible

and some men got more than others. The weaker and sicker ones got the least

as the stronger ones crawled over them to get a second helping. Some men

died, their already weakened bodies unable to bear the stress and conditions

on the Nissyo. During the day, their bodies were taken up on deck and slipped

into the sea with Chaplain Reilley committing their souls to the Almighty.

Several prisoners went berserk and had to be held down until they became

too weak to resist.

The first leg of our miserable journey took us north along the west coast

of Luzon and then across to the Formosan Strait to the west of what is now

Taiwan. Conditions did not improve greatly enroute. The noise, the filth,

the smell and the tension went on 24 hours a day in my hold. I expect it

did in the aft hold also. After a day or so, a few men were allowed on top

deck for a short time. A gulp or two of fresh sea air can be refreshing on

any cruise, but on one such as ours it was as precious as food and water.

I made it to the top deck several times on this part of the trip and was

rewarded with a salt water bath from a pressure hose played on us by some

of the ship's crew of Japanese civilian sailors. The only bad part of that

was then having to go back down in that stinking hold again.

I spent some of my time weaving my way around my half-naked

comrades trying to find and visit with friends. That is when I was not waiting

in line for my bit of rice and water or the other line to get rid of it later

in the old scum bucket. I found only a few: There was Technical Sergeant

Jack Rauhof, the drum major of my outfit, the 4th Marines Band (more

lately known as the 3rd Platoon, E Company, 2nd Battalion), Privates First

Class Monford P. Charleton, S. W. Stephens, and John P.

Latham. All former bandsmen. Another, Leland H. Montgomery,

was also aboard but I didn't know it at the time. He was one of the Manila

Port Area work detail that had been waiting on the dock the day we boarded

the ship. I spent some of my time weaving my way around my half-naked

comrades trying to find and visit with friends. That is when I was not waiting

in line for my bit of rice and water or the other line to get rid of it later

in the old scum bucket. I found only a few: There was Technical Sergeant

Jack Rauhof, the drum major of my outfit, the 4th Marines Band (more

lately known as the 3rd Platoon, E Company, 2nd Battalion), Privates First

Class Monford P. Charleton, S. W. Stephens, and John P.

Latham. All former bandsmen. Another, Leland H. Montgomery,

was also aboard but I didn't know it at the time. He was one of the Manila

Port Area work detail that had been waiting on the dock the day we boarded

the ship.

It was Montgomery who helped me considerably with information about the Nissyo

voyage. He remembers details about the ship and the trip, often in a different

way than I do. But as he explains it, "Everyone saw his situation from their

own point of view...". We do agree that it was a very miserable ordeal from

the first hour in Manila to the last moment in Moji, Japan.

The ship had been made in Europe and sold to the Japanese sometime well before

the war. Montgomery remembers seeing a bronze plaque labeling the vessel's

origin, size, and other details. He thought it was a rather modern ship designed

originally for carrying cargo. It was fitted with booms and winches to lower

and remove stuff in nets. For sure it was not well designed to carry large

numbers of troops at all.

New Friends...

I also made a new friend or two on this not-so-pleasurable cruise as well.

Strangely they were staff noncommissioned officers and older than myself

but the condition of being a POW had a leveling effect on men, who in normal

circumstances, would not become close friends. Staff Sergeant Michael

Oss and I shared the same two or three square feet of iron deck for

almost the whole trip. He saved my spot for me and I saved his for him when

we had to leave it. We slept leaning against one another when we could both

get room to sit, otherwise one would sit while the other stood and tried

to keep the pack from trampling upon us.

I met Staff Sergeant E. D. Smith who was old enough to be my dad already

and reminded me of him sometimes. He was quiet, stiff and had a hard as nails

personality. He demanded respect with a bearing that he carried with him

despite his terrible degradation. Why we hit it off, I have no idea. We became

warm friends until his last days soon after the war. He helped bolster my

courage and strength to endure not only the hell ship experience but the

remaining year of our captivity.

Our first port of call was Takao, Taiwan. We were surprised and exhilarated

by the complete opening of the hatch over our heads and being allowed to

climb out and scatter ourselves around the Forward well deck. It was refreshing

to see the green hills that formed a colorful background to the port area

docks where we were tied up. I tried to imagine what might be going on out

there in what appeared to be a very beautiful place. Of course, most any

place looked mighty nice when compared to the inside of the ship's hold.

The hatch was opened on the deck of our iron stateroom in order that the

crew and some native stevedores could lower many 56-kilo bags of brown sugar

into the hold underneath. We spent the loading time watching the boom, winch

and net operators hoist the bags up from the dock to which the ship was tied

and lower the sweet stuff into the ship. We hungry men wrung our hands waiting

for the time when, after we had gotten underway again, that we might get

our hands on some of it.

Looking around on dockside, there were warehouses as far as we could see

with huge Japanese character writing on the walls -- writing in blue and

green that we couldn't understand. There were stevedores in blue denims with

little, white towels wrapped around their heads, women in pantaloons and

men in shorts, and Japanese sailors and soldiers eating bananas and carrying

little boxes on and off our ship -- goodies we supposed, the things soldiers

and sailors crave at sea and go wild for when they first get ashore. There

was none of it for us. We'd be lucky if we could just get to some of the

sugar.

I was fortunate to spend a little extra time up on the deck while the hatches

were open and the ship was being loaded. I even had my little ration of rice

up there in the clean air -- strange smelling because it was fresh. It was

hot -- but it was clean, like Nebraska in summer. Thirst was a problem. No

one came around and issued me any water in a canteen cup I had somehow acquired.

I crawled beneath the workings of a steam winch that was not being used at

the time, more to hide than anything else, so I wouldn't have to return to

the ship's hold. I found a valve leaking live steam against the heavy metal

and water was condensing off of it. Holding my cup under the drip, I eventually

collected about a half cup of water. Except for a bit of oil, it was pure,

warm and refreshing. I stayed as long as I dared. As I returned to my place

in the hold, I caught a blast of the foul air and of the yellow bucket. It

shook me to my bones.

"To the rail, you fool! into the water!" something said inside of me. I shook

my head and drowned the temptation.

Considering where I was I didn't have a chance in a million for escape.

Furthermore, my effort would have been worse for the 1490 or so others in

the crawling mass of humanity that lay below. The shooting rule of 10 for

one still held. Maybe this time it would be upped to a 100 to 1.I couldn't

be responsible for any life but my own.

"You're insane not to do it." I was saying to me as my feet went step by

step down the ladder. "You're not in your right mind to go back."

Then, I was down, with my tortured fellow beings, still talking to myself.

Most of us, realizing the futility of battles, had stopped fighting with

one another. We tried to play cards. But there wasn't really room for that.

And anyway, have you ever tried to hear a bid, or a bet, or a call over the

roar of 750 men?

"Anyone with leadership could take over this ship. ANYONE with leadership.

You don't have the guts. We outnumber them seven or eight to one. YOU don't

have the guts!"

But my sane self answered.

"There's nobody among us that knows how to run this ship!"

Then I felt better.

Some of the men couldn't wait to get into the sugar and went to help themselves.

That was a foolish thing to do. Too much sugar dries a person out and there

was not enough water to go with it. I had a sweet tooth and the temptation

was great to eat all that was offered me; it was all I could do to keep my

self control. I didn't want to develop a case of diarrhea either what with

the sanitation facilities being what they were. Our hosts had warned against

thievery of the sugar and threatened severe punishment.

Fortunately, nobody was caught.

Those of us who could see the midnight blue sky through the open hatch of

our hold knew that dawn had not yet come when we were pulled away from the

dock and left Takao harbor and chugged northward.

We rolled, we pitched, we moved along in a not so gentle sea, up and down,

up and down, back and forth...proceeding.

As our beards grew, we could see the blue sky above the open hatch, then

the midnight sky.

It was my turn to sit close under the hatch and look at the deep purple above

like a giant television screen filled with the light of a million stars.

The date was July 26th, 1944. I had no watch but I learned years later it

was nearly 2:11AM. I leaned back against the legs of my new found shipmate,

Michael "Mike" Oss.

Suddenly, the "screen" turned red, blotting out the stars and melting the

deep purple. Almost immediately we heard it --

"Boom!"

The ship shuddered as it veered sharply in another direction. When the stars

appeared again they skewed across my view indicating that the ship was taking

another heading. Obviously it was being put in a sharply, zigzag motion.

Under Attack...

Another big explosive flash shot across the sky. This time large shadowy

chunks of what had once been part of a ship sailed across the field of view.

Already our ship's siren had sounded, and guards were rushing about the deck

above us, hurrying to cover the hatch in case we all tried to evacuate the

hold. Escorting destroyers in our convoy began to discharge depth bombs,

some close, some far.

What had happened? Well, obviously, the convoy was under attack by submarines.

A nearby ship us had been struck and, my first thought was that it was an

oil tanker. Nothing else could have made such a blast. It was many years

later that I learned more of the story. In the book, "Silent Victory", by

Blair, I found the account of this strike. It had been made by the USS Crevale

commanded by Frank Walker; the USS Flasher commanded by Ruben Whitaker; and

USS Angler commanded by Franklin Hess. The Flasher fired all six of its remaining

torpedoes. One ran through the convoy formation, probably narrowly missing

our fragile Nissyo Maru and had sunk the Otoriyama Maru, a 5280 ton oiler.

Not all the booming sounds of explosions that continued during the night

were made by depth charging escorts. The pack took another freighter, the

Tosan Maru down later in the morning in what must have been a far larger

convoy than we had imagined it ever to be. It was an exciting night and one

that proved that a super, divine, guiding hand must surely have watched over

us.

A few more of our comrades died in the remaining days at sea enroute to Japan.

Dysentery, malaria, and dehydration plagued us the rest of the way in our

iron dungeon with red-lead walls. Large water blisters broke out on the bodies

of nearly everyone, attributed by the knowledgeable, to the closeness and

lack of any means to keep clean. Those who had contact with our guards complained

and so instructions were passed to count off groups of 20 men.

"Come topside."

It was one of the few orders given by the Japanese that I ever heard cheered.

Up the ladder we scrambled, those of us who still had the strength to climb

the red iron rungs. Some did not.

A hose played on us. We shivered with pleasure from a forceful stream of

water pumped out of the azure blue sea. I washed my only T-shirt in the salty

stuff but, instead of trying to dry it, I rolled it up around my neck to

keep cooler when I had to return to the fetid hold. It would dry soon enough.

So would our skinny bodies which were then left sticky with moist salt but

nevertheless, refreshed.

Probably none was happier about our topside baths than the men on latrine

detail. There were toilets on deck, wooden affairs built on platforms

cantilevered off the deck over the sea. During the time we were allowed up

there -- 20 allotted minutes and if you were smart, an hour and a half --

you could use them. That eased the work of the latrine detail.

Now the air was different. It was hot because it was summer, but it had less

of the heaviness of tropical air and more the pungency of the Temperate Zone.

Islands on the Horizon...

When we were topside, we could see a lot of little islands. Little, green

punctuation marks in a blue, sea-story book. Those in the distance looked

like little greenish dots peeking over the horizon. Some looked too small

to have inhabitants, but the larger of them had buck-skin tan, shore lines

with slivers of fishing boats beached upon them.

Later, the land fall was continuous and the shoreline longer with occasional

interruptions that erased the sands now and then. We knew that we had reached

a larger land. Our joy was not unlike that which gladdens the heart of any

sailor who has been at sea for a long time and anxious to set foot on God's

great, green earth. What we could see of it now surely looked inviting. Imagine

our disappointment when, after we had drawn so close, that the ship dropped

its anchor. Most of us would have gladly tried to wade or swim ashore, so

anxious we were to disembark the terrible Nissyo Maru.

Some in our hold knew that we had reached the port of Moji, Kyushu

Japan, the southernmost of Japan's three big islands. The ship was later

joined by a pilot and a small, harbor vessel, and pulled into and tied up

to the docks. We had to wait all night while a Japanese longshoremen crew

came aboard, opened the hatches and unloaded the sugar in the ship brought

from Formosa (Taiwan ). The noises of the winches and the yelling of the

crew made too much racket to allow sleeping; we waited awake all night to

disembark the ship.

Vague thoughts of escaping now came to mind. It might have been easy to slip

away in the confusion. One was not likely to be missed and the surrounding

area looked inviting, but a Caucasian prisoner of war would have been as

conspicuous as a cherry in a bowl of rice. One could not expect to be hidden

and protected in the enemy's homeland which had been common for the brave

escapees in the Philippines. Recapture would likely be swift and brutally

final.

Anyway, were we not guests of the Emperor? Guests in a land famous for gracious

hospitality. Pitifully, they tried to make it appear so. Each debarking man

was given back some of the clothing worn and carried aboard and dropped so

unceremoniously into the hold some 17 long, hot days before. But no one got

his own or, necessarily, a good fit. Some of us were handed smashed, gray

and blue sun helmets of the old Filipino Army. As part of my "uniform," I

received a pair of yellow-green Japanese army trousers, worn, soiled and

threadbare, an oversized pair of army shoes and a ragged, dirty shirt that

I thought would be better than nothing.

One by one we were marched, or carried, over the gangway. It was not the

brutal disembarkation we experienced when we first came aboard. As we reached

the dock, a weak solution of some chemical was sprayed on and over each of

us so that whatever vile disease we were bringing to the land of the Rising

Sun would not infect them. The old technician who sprayed me did not seem

very serious about it -- just the normal operating procedure, I guessed.

What most of us were suffering was the lack of good ripe apples, hard boiled

eggs and fried chicken -- to name a few of the medicines that would have

restored and preserved what health we still had.

Other writers such as Manny Lawton, Colonel E. B. Miller and Preston Hubbard

have stated that the suffering of prisoners on hell ships was among the worst

atrocities of the war in the Pacific. Hubbard writes, "...Hell Ships do not

lend themselves to varied viewpoints or contrasting scenes. The damned, dark

world of Hell Ships lies buried beyond the reach of memory or imagination."

He feels that is the reason there has been no motion picture made of such

an experience. There is nothing to compare it to and good art must have contrast.

No doubt true in part but, nowadays, with the motion picture industry dominated

by the Japanese, it is most unlikely any recollection of this phase of World

War II infamy will be so recorded. As Dr. Hubbard so aptly writes,

"Unfortunately, they (remembrances of Hell Ships) will probably vanish from

the thoughts of mankind when the last survivor has gone to his grave."

As I rewrite the lines of an original draft of this account, written almost

50 years ago, I can hardly believe how we suffered. I am repelled by the

memory of the hideous voyage of the Nissyo Maru. I can scarcely believe it

really happened anymore. It is not much consolation to consider that at least

the torpedoes missed the ship we were in and no bombs from friendly war planes

struck us as they did the Arisan, Orokyo, Enoura Marus and a number of others.

Many prisoners were killed, drowned and died in these infamous ships. It

is almost impossible to recall that among us were those who hoped our misery

would end quickly by a torpedo that might mercifully explode into us with

a flood of cooling, cleansing water, washing away the terror and the incredible

filth and the noise of our teeming mass. It was, chilling as it may seem

now, true and I can hardly expect anyone who was not there to understand

or really believe it.

The Lord was merciful to our group, most of us, anyway, and we survived.

It was not the end of our suffering; we had another year of captivity still

ahead. We knew that eventually the real horrors of war would reach Japan's

precious homeland. We did not know that it had drawn as close as it had.

Neither did we know very much about how terrible the reckoning would be for

them.

Now, in the Land of the Rising Sun, captivity as we knew it was a new dawning.

Gone were the days where the fence was such a distance from where we slept

that days might go by out of sight of even a single, enemy guard. This was

true only in the large camps but even at Clark Field, the interface with

our captors was often not long or frequent for some of us. It would be different

here. From the moment we left the Nissyo Maru, the Japanese would be in "our

face" constantly.

We survivors of the voyage of the Nissyo Maru were lined up in units of a

100 each. What a crusty, filthy-looking bearded bunch we were. Any patriotic

Japanese civilian thereabouts must have wondered what was taking his army

more than three years to beat down such a motley enemy. Getting off that

terrible ship was immense relief. A detachment of horse cavalry stood by,

apparently waiting to board the vessel after it had been unloaded. They were

welcome to it, I'm sure, but I know they would not like it, especially the

horses. I could not believe that any amount of cleaning, decontaminating

or fumigating would make it fit for any purpose after we left it. I was amazed

to learn afterwards that the Nissyo survived the war and plied the shipping

lanes for some time after the war -- the only "hell ship" to escape being

sunk. Except for those who died during the trip and as a result of the stress

later, it was a lucky ship and we survivors were fortunate to be in her and

not one of the others.

We were marched to an auditorium, a single story, wooden building badly in

need of repair. We were assigned to sections and given a meal consisting

of a rice ball mixed with a few, cooked soya beans and some kind of

unidentifiable leafy vegetable that may have once been green but now was

a deep, vile viridian after having been cooked in soy sauce. No matter, it

was welcome and delicious but, we wanted water as much as food.

"Don't drink the water in the washroom. It is polluted," we were warned.

Nearly dehydrated now, we ignored the message. Our bodies must now be immune

to Japan's friendly microbes. After those in the tropics, whatever we might

encounter at this time could not hurt us much. Most would take the chance.

I did and drank as much cool water as I wanted. It was almost too much to

believe. The faucets were left running as men held whatever cup, can or bottle

they could locate to catch a drink. Hardly a drop ever hit the floor.

Chapter Seven

Where the Birds don't sing and the Flowers don't smell...

All afternoon we sat, we lay around, in the auditorium trying to talk to

Japanese guards, those who could and would speak a little English. One was

a rather gnarled, swarthy, older man that we quickly named "Hawaiian Joe."

His English was amazingly fluent with hardly an accent. He claimed to have

lived many years in Hawaii but had returned to his homeland for retirement.

At his government's insistence, he had to work, so he had taken on a job

of guarding POWs. He wore the uniform of the Nittetsu-Futase Tanko

Kaisha coal mining company and carried a wooden replica of an issue rifle

tipped with a sharpened metal bayonet.

"Joe" informed us that our group was going to a nice place where there was

plenty of good food and many cigarettes. He was right about the nouns but,

as we were to discover, wrong about his adjectives.

There was plenty of room in the large auditorium not like the cramped space

in the ship. We spread out so we could sit or lie without touching anyone

near. After being pressed against someone else's body for 17days it was just

sheer joy to have a little room. Some guys joked about it now, "Hey move

a little closer, you seem so far away." Comic relief often follows great

stress and pressure.

The great relief of being off the ship began to wear off; apprehensions of

what lie ahead for us invaded our thoughts. Of course, it could hardly be

worse than the Hell Ship Nissyo but, if the place we were going to really

was really worse, then surviving longer would be unlikely. A few men in our

group were finding it difficult just to walk and one or two could not at

all. We thought it was the dehydration.

In the dead of the night, we half-dead, sleepy, groggy POWs were hustled

off to a nearby railway and loaded onto a passenger train. The car I went

in was smaller than an American railway car. The seats were smaller and the

windows were smaller. Cuspidors were countersunk flush with the floor.

Most of us quickly dozed off or went soundly to sleep not even noticing when

the car lurched and the train moved. Those who were still awake got no look

at our surroundings or the countryside. "Do not raise blinds!" was the order.

I hope it stemmed from a Japanese desire not to have seen their homeland

wrecked by our Yank planes.

When we reached the train's destination we debarked onto the platform of

a fairly large city. Later, we were to learn this was Shin Iizuka in Fukuoka

province. It was early morning and all the shops and places of business were

still closed and shuttered. Many appeared to be boarded up permanently. Most

of the people in the streets were either older males wearing the peaked caps

like the military or school children carrying backpacks. The young boys were

all dressed in little uniforms with military-style caps, too. The few women

who were about were dressed in light pantaloons and wrapped with a light

kimono tied with a sash. Not much attractive about any of them. It had been

many months since we had seen any women at that close range.

Take a Hike...

From the rather modern-looking railway station we were ordered to hike --

silly word. Some lagged, some limped because of ill-fitting shoes. Some slogged

along the cinder-coated streets barefooted. Those that could not walk at

all were carried off and loaded onto trucks with strange looking contraptions

affixed to them for cooking charcoal to make engine fuel.

It was not far from Shin Iizuka to the smaller, coal mining town of Futase

City -- three or four miles maybe, but the long days in the Hell Ship had

done us in. It seemed as long as the Great Wall of China. We finally came

to an unpainted, 10-foot tall, wooden fence atop a small hill. The fence

was topped with sharpened spikes of bamboo. Two, large double gates, large

enough to admit trucks, opened and we were marched in. The gates closed behind

us. Welcome to Futase, Camp 10.

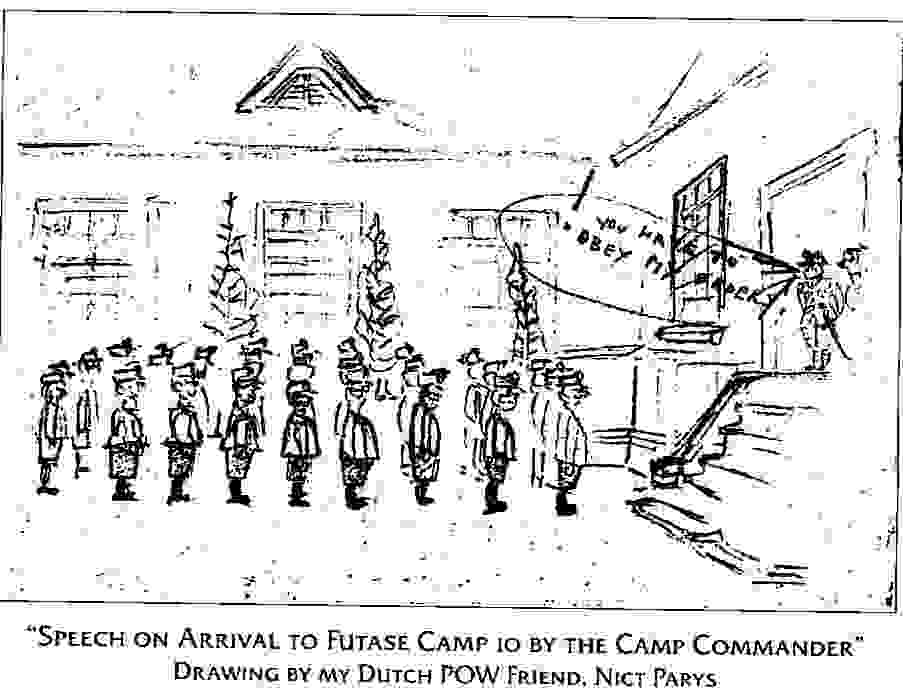

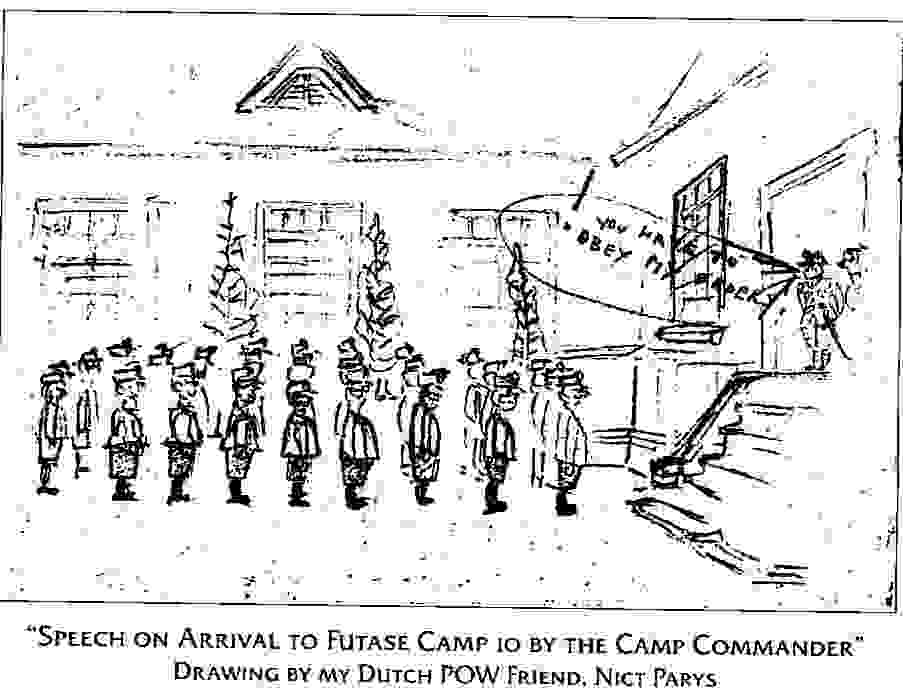

We were lined up and "bango-ed," the word for counting off. Around us were

a number of armed soldiers led by a senior sergeant. Looking us over was

a young and rather handsome Japanese officer, a long saber dangling from

a belt. His olive-green uniform had a richer, cleaner quality about it and

he wore a clean looking white shirt. His peaked cap matched his trousers

and was slightly decorated with several blue threads sewn around it from

front to back. He took no part in the "welcome" procedure. Several older

men wearing gray uniforms the color of dirty putty did. Each was decorated

with sewn-on patches of 5 gold stars, each one slightly smaller than the

other. We learned eventually that the insignia denoted they were members

of the Japanese Propaganda Corps. They may have had a better name for themselves

but that is what we called them. There were about six men in that group;

two of them had arms missing, one a right and another a left. We guessed

they were disability-retired soldiers now pressed into service to handle

POW's.

They quickly established the impression among us that they had plenty of

authority. They acted mean and angry from the first and remained that way

until the very end.

Additionally there were more of the older men like Hawaiian Joe, all carrying

stick rifles with fixed (real) bayonets. All wore the same civilian garb:

light striped shirts, thin cotton trousers in a gray pattern and the familiar

Japanese army peaked cap with small crescent bills and laced in the back

to provide adjustments for "one size fits all." A distinguishing feature,

however, was the enameled pin fixed in place of the army gold star on the

crest of each cap. A large Arabic letter S was framed in a field of white

enamel bordered by red and brass decorations. These were employees of the

Nittetsu-Futase Tanko Kaisha hired to guard and handle prisoners of war.

All of them seemed to be last in the pecking order and rarely hassled or

gave us much trouble.

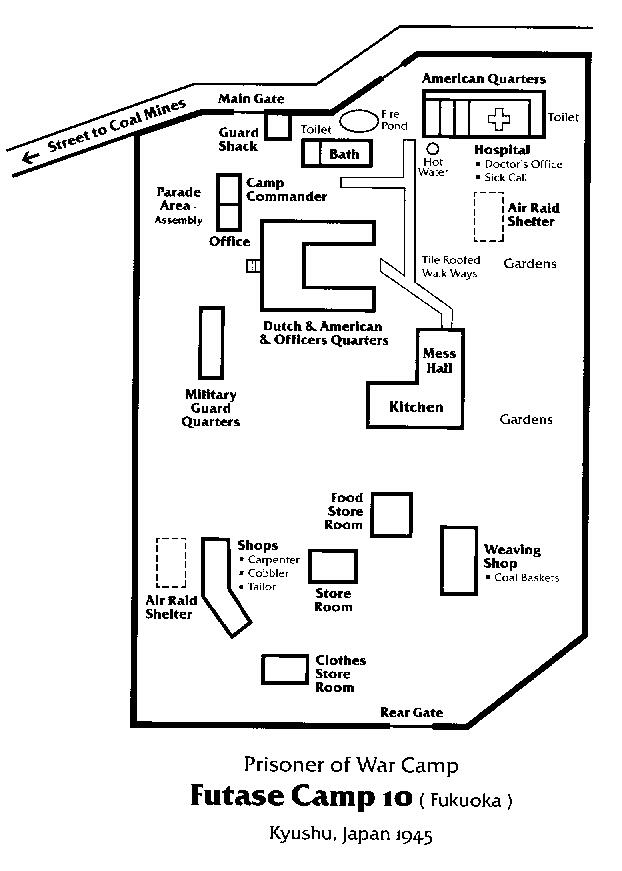

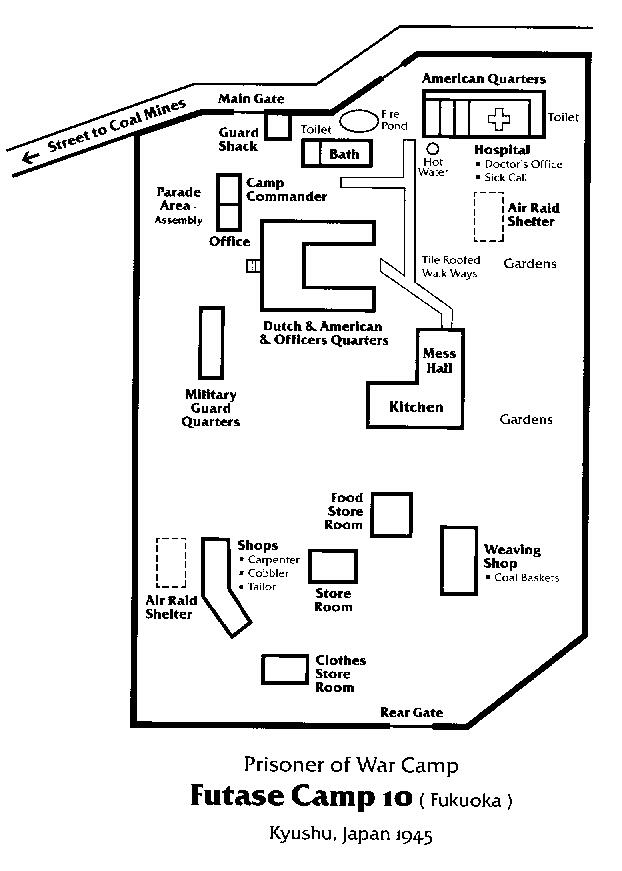

Just inside the gate was a guardhouse the whole front of which was the door.

Inside was a table and a couple chairs for the watch on duty. It overlooked

the small assembly area, the size of a couple tennis courts. A small, wooden

platform with several wooden steps leading up to it was placed in front of

the first low, long building that housed the Japanese Camp Commander's office

and living quarters. Beyond that, bordering the same side of the square was

a larger, one story, barracks-like building that housed the Japanese army

detachment of about a dozen soldiers.

The gap between the two buildings led to a large, two story building in the

shape of the letter U. It could have been a school or even a barracks in

prior years; now it housed some 200 prisoners of war taken in the Dutch East

Indies, Java, Sumatra, places like that.

None of the present inmates came forth to greet us with the exception of

one Hollander who was speaking what seemed to be fluent Japanese and acted

as both a camp official and an interpreter. The comments being made by the

Japanese, we learned later, were such things as: "These prisoners are unfit

for anything;" "little work they can do;" and "the smell hurts the nose."

He became known only as Lieutenant Braber.

After the Japanese were satisfied all were present and accounted for we were

led back in to the camp where the building seemed to receive less care. We

passed the Aso, the punishment cell. A tiny box of hideous proportions and

design. Then, on by the bath house which housed a large concrete soaking

tub about twice the size of a farm stock tank. We proceeded under tiled,

covered walkways to a long, narrow building that perhaps had been a warehouse.

This was to be our home for the next 13 months. The building had recently

been remodeled to accommodate the expected arrival of more POWs. Three rooms

to house about 40 men had been parceled off a hall leading to the back. Each

room had two platforms built off the floor on each side of a center aisle,

one above the other. The platforms were covered with the straw mats common

to most Japanese households called tatami mats. A single shelf lined the

back wall of each platform. At the end of the aisle was a small, casemate

window. Except for air entering the rooms from the hall, it was the only

ventilation. The first of these rooms was to be my home for the coming year.

The office and examination room was located between our sleeping rooms and

the infirmary. A Japanese doctor, "Ishi" we called him, (the Japanese word

for doctor is pronounced eesha) was in charge there. His name was Yoshiwaka

Suenaga. His hard-fisted medical assistant was the ever-terrorizing Sugi

Horibumu. Next and beyond that was a larger room with platforms on either

side for the sick. It was called the "Nushisu" or sick room. At the end across

the back of the building was the latrine.

I found myself housed with some members of the original 4th Marines Band

(E24) with whom I had played in Shanghai a few years before. My room leader

was Technical Sergeant Jackson P. Rauhof, the drum major and leader of my

platoon on Corregidor. Others in my room were Platoon Sergeant Felix

McCool, Staff Sergeant E. D. Smith, and PFC Edward "Eddie"

Howe. Next door were others from the band: PFC Cedric Stephens

and PFC Monford P. Charleton. A few of the recently arrived American contingent

were housed among the Dutchmen in the big building. Among them were Corporal

Franklin Boyer, another bandsman.

Our captors decided that two weeks rest would be enough to restore us before

we would be put to work in the coal mines. Many, however, would not recover

enough to do so, but some who were fearful of working in coal mines would

manage to stay "unwell" enough to avoid it for the whole of our stay.

For two weeks we did not go to work. We exercised in the sun on a field just

outside the camp. We were taught certain Japanese words peculiar to coal

mining which would be our occupation. We learned a little close order drill

using Japanese commands for: forward march, right face, to the rear which

our captors believed would build up our strength so that we could work. We

were even allowed to play a couple of strange ball games. We did it with

little enthusiasm although most of us knew that what we were doing would

help get our strength back. It was the purpose they intended to put it to

that had us worried. And they gave us food which, by previous standards,

we could consider ample.

At the end of two weeks, Captain Roscoe Price, our senior American

officer persuaded the Japanese to give us more time. He must have been surprised

at the success of that, for the Japs were not easily dealt with.

Unlike camp life in the Philippines where we pretty much governed by ourselves

with a minimum of supervision by our captors, this camp was run very closely

by the JPCs (disabled ex-soldiers) and civilian employees of the mining company

and the military. The soldiers were by far the most brutal, along with Sugi,

the medic, who took a sadistic joy in tormenting anybody, particularly sick

Americans. His usual weapon was a samurai saber, scabbard and all.

Most of the guards and troop handlers were laid back and didn't bother or

interfere with us much. There were a few that were just down right mean and

meddlesome all the time. A few more were sadistic. "Right Arm" and "Left

Arm" were the two most notorious prisoner beaters. Because they only had

one arm each it seemed to please them that they had us where we could not

retaliate from the sticks they carried to flail us with. Sometimes they would

just sock us with their remaining bare fists. They were the most hated of

the JPCs. "Smiley" was one who wore a deceiving grin most of the time, and

was generally a mild driver. I was to discover later that he had a pretty

good left hook. Whatever his disability was, it did not lessen the power

of his punch.

The camp routine was very rigid, of course. There was a time to do everything

and many times when doing almost any other thing was forbidden. We ate, smoked,

slept and went to the toilet at the sound of a bell. Anyone caught doing

the wrong thing between bells was punished on the spot; slapped, punched

and kicked if he did not get up quick enough. The fastest response back to

a position of a soldier at attention was always the quickest way to halt

the attack. It was hard to learn. Otherwise, the punishment was brutal and

complete.

One of the more serious offenses was smoking after the bell rang to stop;

it was worse yet to begin before the starting bell. It was usually a 15-minute

period, long enough if you didn't have to wait to share a part of the cigarette

or wait to get your butt lighted. Since no matches or lighters were allowed,

someone had to run to the kitchen located clear across the compound and bring

back an ember or something. The result was that some fellows did not get

theirs lighted until almost time for the bell to ring. Because the guards

couldn't be everywhere at once, the period could be over run. Not without

some risk and the penalty was severe.

My bunk mate, Eddie Howe and I were caught in this "crime" one noon. The

last dying rings of the bell had not even faded away when the Japanese First

Sergeant, still limping from his China war wound, I suppose, came bursting

in the door. And here we were taking just one last puff. With a raised right

and left he knocked us both to the floor. I jumped back to my feet before

he could kick me, preferring to take another blow I could roll with to being

kicked. Eddie may have been struck harder and didn't get up. He was kicked

with a series of blows and beaten again with a stick the size of a riding

crop. It took some heat off me, but I stood there with fists clenched wishing

I could help him up. Defending him would have sealed my fate and his too,

I expect. There is nothing so easily riled to uncontrollable anger as a wounded

Japanese First Sergeant. It was not our first beating nor would it be the

last, but we boys from the Philippines may have been able to take it better

than the Japanese home boys knew. Things like this created a tension which

always persisted in the camp.

The day came when we were turned into coal miners on the night shift. I

remembered what Professor Clark, my geology teacher had said about the brown,

coal mines of Japan. She had hoped I could visit them one day.

And here I was! I'm sure it was not under these conditions that she had in

mind. We had been issued a gauze-thin blouse, light cotton shorts, sandals

made of rice straw and a black miner's cap made of rubberized cotton with

an Indian red, fiber bracket to hold a lamp.

The company we were consigned to operated two mines in this local. The first

was a deep vertical shaft called Honko. A huge multi-wheeled lift was built

over it; all around the opening were buildings of many sizes housing power

plants with huge tall, chimneys, offices, and coal sorting apparatus. Within

this complex we called the "Fabrique" was the auditorium decorated with Japanese

flags and company insignia. Before we were taken to work underneath we "stood

up" for some kind of a formation designed to inspire hard work and safety.

As part of our training for coal mining we were taught a number of Japanese

words: Abunai, for danger; Shigotoe, for work; Ebu, for coal basket; Kakita,

a short handled hoe for raking coal into the Ebu; and Juji, for pickaxe.

Little was said about Yasimei for rest, or Shigotoe awari for stop work.

Somehow we had learned those words before ever reaching Japan.

Down in the Mines...

The cars descended, a couple to each lift. It seemed that we were going slowly.

The electric lamps connected to our caps bobbed around as the new American

crew searched the walls of the pit trying to see where and what we were getting

into. The change in air pressure bothered my ears; I had to swallow to restore

equilibrium like coming down a mountain. Some said the foot of the shaft

was a 1000 meters below the surface. More than likely it was for it took

a long time before the lift stop and the gates opened. We stood in a huge

gallery or tunnel. The walls and overhead were cemented over and lined with

many dim incandescent lights.

When all had reached the bottom, we assembled and later divided off into

work parties, some large, some small. I was assigned to one of the latter.

We were told what we were going to do but had not yet learned enough to

understand. We marched out of the lighted area and through huge, double doors

into a much smaller tunnel lighted now only by the lamps on our caps. We

hiked along the tiny railway tracks laid in the center. Other tunnels branched

off to the right and left of the one we were in. Up ahead, the racket of

an approaching Hako (box), an iron tub-like cart was heard. We all had to

cling to either sides of the tunnel to let the car pass. Two bent-over bodies

were pushing it; who they were we couldn't see but we supposed they were

other slave creatures like ourselves.

Reaching our work area, a Horye, we found it was our job to help our work

leader, an older Japanese civilian to install shoring along the walls and

overhead of a tunnel being extended. We had a pneumatic drill, it's long

hose connected to a pipe running along the main tunnel and found a car of

pine posts already there to use as shoring. The drill was large and heavy

with a hardened steel bit. It took two men to manage it, drilling inch-diameter

holes in the rock and coal for setting dynamite charges.

Rich deposits of coal, when found, were blasted out and loaded into cars

brought up from the main lateral by another crew. Large rocks were left in

the mine to build pillars to help support the overhead. The mine was humid

and stuffy. The rugged Japanese miner (honcho) in charge had nothing but

contempt at my weakness. I felt he couldn't make up his mind whether to cuff

me or get on with the work. Before it was time to eat the little rice and

sliced pickle radish we had brought to the mine for lunch, it was apparent

to me that I couldn't last the shift no matter what he did. The light shirt

and shorts I wore were soaked with sweat. My grass shoes had begun to

disintegrate. It was slowing me up and I was already dead tired. I knew the

miner would soon start swinging -- at me.

Then fate stepped in. My electric lamp dimmed, its red glow was lessening.

The batteries in the metal box hooked to my waistband were losing their charge.

It wouldn't last long.

"Hey! My lamp is going!" I called attention to my captor. With a curse, he

ordered me back to lift base to get a replacement. Batteries with lamps attached

were drawn from a room topside (kogai), but extra charged batteries were

available at the lift.

I started along the mine track. One hundred yards and two curves away from

my detail, the light went out completely. There I was, many meters deep in

the bowels of Japan, still a couple of miles from a fresh battery. It was

pitch black. Just being underground, thinking of cave-ins and Japan's notorious

earthquakes was terrifying enough; to be without light in these conditions

was very frightful. There was little sound, muffled blasts way off in the

distance occasionally. The opposite direction of those was the way to go,

feeling along the dank tunnel wall and stumbling over the ties and rails

of the car track.

My head struck a low overhead beam.

The little stars were just fading when I heard the clatter of metal wheels.

A string of cars was approaching!

In utter ignorance of the width of the tunnel and the clearances of the cars

and walls, I hugged the stone as the first car passed. Very closely.

I must have exhaled. The second car caught the battery case on my belt and

jerked the connecting cord off my cap. My hand swung out wildly to catch

the cap. Another car scraped my skin. I moved tighter against the wall. Each

car took its token of me.

The rattle faded in the distance. I wiped the cold sweat from my face, groped

about for hat and dead headlight and stumbled on through the darkness. Two

hours more and a dozen hard bumps later, I saw a dim glow. It was the lighted

tunnel near the mine shaft.

I exchanged my dead battery for a good, hot, fresh one. It was made up of

wet hydroxide cells. The caustic electrolyte could cause deep and painful

wounds if it spilled out. The covers on some did not fit tight and prisoners

would be burned. Later, some men learned to use the battery fluid to aggravate

and sustain wounds and sores in order to render themselves unfit for work.

I set out to return to my work place. I don't know how I ever found it and

perhaps would not have done so had it not been for some engineers or supervisors

along the way who shuttled me off in the right directions. Their lamps had

a red circle painted around the lens so they could be recognized. I yelled

"Guan Jin" to each one, hoping they would not recognize me as a loose prisoner

slave wandering around in alone in the mine. I was not stopped and questioned.

It was a very large mine and large numbers of Chinese prisoners and Korean

laborers were worked within its many stapes galleries, and tunnels. Because

of the limits of the lifts the work hours were staggered so that gangs would

come and go and hardly see anything of one another.

When I reached my detail, the honcho was very much on edge and disgusted

with his American miners. They had all eaten their rice and pickle but I

was not given time to eat mine which remained tied up in a rag handkerchief

still in the little wooden (bento) boxes; one larger, one small but neither

containing very much food and looked even less in boxes that could have held

more. I was famished but only managed to eat it on the hike back after work

time had expired. It had been a long, tiring night.

The sky had begun to lighten slightly when we finally reached the surface

after our first ten hours of coal mining. Thankfully, we were allowed to

use the company bath to try and wash some of the grimy coal dust from our

weary bodies. The bathhouse was a huge room almost entirely filled with a

concrete tub, about four feet deep and nearly as large as a tennis court.

At several places, pipes from overhead extended into the steaming water-filled

pool, injected live steam to heat it. A foot-wide trough surrounded it and

a stream of fresh water ran within. Scattered around on the floor and in

the trough were dozens of little, wooden buckets bound with darker, wooden

bands. The idea was to first wash well from the water in the trough and then,

when clean, soak in the warm pool. There was no soap or towel so it was very

difficult to get clean. Most of us used the cloth we had carried our bentos

in as a combination wash cloth and towel. The bath was not segregated sex-wise

and we were mostly amused to see some women using the facility. The few I

saw congregated in one corner and kept to themselves. They showed far less

interest in us than we in them even though these women were not Las Vegas

showgirls. Far from it, in our physical condition only food seemed to occupy

our thoughts.

I worked the Honko mine only for a short while, perhaps an entire shift of

ten days. I expect the honchos my crews worked for gave up on us in disgust,

for I was soon transferred to work the other mine called "Shinko." It was

an old, inclined shaft a couple miles further from Honko over the huge, ancient,

slag heap mountain. Once closed as unproductive and having once been damaged

by earthquakes, it was now opened again for Japan's war effort.

The Shinko shaft had a concrete entrance, nothing elaborate or anything;

over the top of the arc, in English lettering the word SHINKO had been cast

into the structure. Nothing was written in chicken track style of Japanese

lettering. The shaft inclined at about 30 degrees with rail tracks down the

center and steps leading down along the left side. On the rise just above

the opening was a building that housed the motors and winches that lowered

empty Hako cars into the mine and pulled those loaded with coal out.

It was not considered safe to ride in the cars to the coal faces below and

against the rules to do so. The cables only went so far. Then the cars were

unclasped from the cable and handled by prisoners from that point. A Japanese

civilian ran the track and cable system using a hook-like tool about a foot

long to operate the cable clamps. It was a tiny bit like the cable-car system

so famous in San Francisco. The cable Honcho was a wild creature -- always

in high gear shouting words and warnings that meant little to us those first,

few weeks after starting work in the Shinko.

Walking down into the mine was tenuous and tedious. Crews were made up above

ground and assigned to honchos who would escort their work gang of prisoner

slaves down into the mine. At the lower end of the main shaft, lateral tubes

cut off to the left and right. Each lateral was numbered: Migi Itchi (right

one), Hidari Ni (left two), etc. We were told the system of mining was a

kind of technique developed in Belgium. The Hollanders knew more about it

than any of the rest of us and, some of them, the Caucasians particularly,

were assigned to the mine engineer office above ground. The Indonesians were

enslaved at "unskilled" labor along with the rest of us.

Usually the laterals on either side of the mine shaft followed parallel courses

about 100 feet apart. Within the geology of the earth below, deposits of

coal sandwiched with rock and dirt ran between the two, usually at a gentle

angle. The coal was blasted out in sections by the drilling and dynamite

crew, after which we hoe and basket operators, would scoop up the loose coal

and toss it into a conveyor carrying it to a waiting car in the lateral below.

As the process continued, coal was mined during one shift, called "production."

The next shift, called "construction" would move all the machinery and extended

the laterals, and lay more track. The overhead would slowly subside behind

and along the coal faces as everything went forward. Loads of pine poles

were brought down from the upper laterals and used to erect support of the

immediate overhead. Big rocks were also used to build pillars of slag to

help hold up the "roof." These were also used as toilets while under

construction. The Japanese forbid it but there were no other places of

sanitation. In the course of a few days the tremendous pressure of the earth

above would crush the poles and smash the rock pillars (bota maki) to a space

of just a few inches. Some spaces along the conveyor would not allow one

to stand fully erect. Excavation was limited to just enough to get the coal

out and move on. Only along the laterals could short men stand up. Tall men

had to look for special places with head room.

Shinko being closer to the surface was cooler than Honko but there were hardly

any facilities above ground, no heated assembly room, no bathhouse and no

coal processing and sorting unit. The coal cars were fastened to other cable

systems and transported over the slag heap mountain to the Honko system.

A vertical shaft was located at the rear of the mine for ventilation. We

called it an escape tunnel. If there was a ladder in it, I don't know, because

I only saw it from topside and I never went close. It gave us a sense of

security in case of a major cave-in, knowing there was another way out.

There were other small details performing general maintenance tasks in the

laterals. Usually these were better jobs than with the big crews, but they

could be worse depending on the Honcho or Japanese miner in charge.

I often worked for an older man we called the "Skunk" because he gave off

such a strong smell. I expect we prisoners did not smell ever so sweet to

him either, but he was a kindly old fellow and didn't complain about it.

He was always in good humor and was never mean or nasty with his crews. It

seemed to us that he had once been retired and compelled to work again in

order to qualify for larger rations. Working for the Skunk meant starting

to work later, longer rest and bento (lunch) breaks and an earlier quitting

time. He often asked for "go hako hatchi" my prisoner number, 508. I was

always pleased when he did, but never knew why. It was not that I was an

eager beaver worker. I doubt that my work ethic impressed him. It may have

been that I just talked to him. He taught me Japanese words and how to say

them and seemed patient with a slow learner and what must have been a gawd-awful

accent.

The Skunk's prize possession was a big, railroad-style, pocket watch. He

carried it in his pocket wrapped in about two yards by two inch wide felt

cloth. It was his habit to declare a short rest period every night (he always

worked nights) upon reaching the work site. Then he would take out his watch,

slowly unwrap it, check the time, give the winder a couple twists and carefully

wrap it back up in what once may have been an old yellow army legging.

During the course of the night I would sometimes ask, "Mo nonji desu ka"

(what time is it?). Most often he would stop what he was doing and break

out his watch, unwrap it slowly and then say, "Ema kuji han desu." (nine

thirty or whatever it was). We got a little extra rest that way, but he never

worked us hard. He usually took about three of us to his task. That was mainly

repairing rotten or crushed overhead timbers in the main laterals. The old

ones were removed and the rock and shale cleaned up around where they had

been. If there was any coal found, it had to be loaded into his car, tagged

with his metal ID tag, and new supports cut and put into place.

PRISONER OF WAR CAMPS IN JAPAN

& JAPANESE CONTROLLED AREAS

AS TAKEN FROM REPORTS OF

INTERNED AMERICAN PRISONERS LIAISON & RESEARCH BRANCH

AMERICAN PRISONER OF WAR INFORMATION BUREAU

by JOHN B. GIBBS 31 July 1946

FUKUOKA CAMP NO. 10 FUTASE, KYUSHU ISLAND

1. LOCATION:

This camp, on the crest of an ancient slag and rock pile, was located between

the villages of Futase & Iizuka, approximately 50 miles from Moji on

the north and 45 miles from Fukuoka on the west. Nakatsu, on the Inland Sea,

was approximately 35 miles northeast of Futase. The coordinates of the latter

are 33°26'N., 131°05'E.

Size of compound was 300' x 300' and was surrounded by a 10' wood fence.

Bamboo pilings sharp ends up and pointing inward, had been fastened into

the barricade at the top. An alarm system had been fastened in the fence.

The project was mining coal in the mines of Honko & Shinko Mining Company.

It was a typical mining town. The power plant of the Mining Co. was located

here and was topped by 4 smoke stacks said to be about 100 feet high.

2. PRISONER PERSONNEL:

A detail of 200 American prisoners from the Philippines reached this camp