B. Beheading of airmen

(Click

on image for 29K enlargement)

(Click

on image for 29K enlargement)

CAPTION: "American fliers at Fukuoka Prison suffered

this fate

just after

the Emperor announced surrender." (From the Fall of

Japan by

Craig)

NOTE: Actually, the photo shows a captured Australian Sargeant Leonard

Siffleet

being beheaded by Yasuno Chikao in Aitape, New Guinea on October 24,

1943;

from the Australian War Memorial, original caption: "Aitape, New

Guinea.

24 October 1943. A photograph found on the body of a dead Japanese

soldier

showing NX143314 Sergeant (Sgt) Leonard G. Siffleet of "M" Special

Unit,

wearing a blindfold and with his arms tied, about to be beheaded with a

sword

by Yasuno Chikao. The execution was ordered by Vice Admiral Kamada, the

commander

of the Japanese Naval Forces at Aitape. Sgt Siffleet was captured with

Private

(Pte) Pattiwahl and Pte Reharin, Ambonese members of the Netherlands

East

Indies Forces, whilst engaged in reconnaissance behind the Japanese

lines.

Yasuno Chikao died before the end of the war."

See this report for an account given by a Japanese POW who was at the scene of an earlier beheading in Salamaua (CAUTION: VERY grim).

1. At Fukuoka Municipal Girls' High School (Google Satellite)

On June 20, 1945, the day after Fukuoka was firebombed, eight airmen out of the twenty being held at the HQ detention center were taken to Fukuoka Municipal Girls' High School (now Akasaka Elementary School) just to the south, where they were made to stand in the schoolyard and then hacked with swords and beheaded.

| On the night of June 19, a

heavy

bombing raid destroyed a large section of Fukuoka

city. Bombs landed near Army headquarters, and the Legal Section's

building burned in the ensuing fire. Maj. Gen. Kyusaku Fukushima,

Assistant Chief of Staff, Western Army, was in the Intelligence office

of the Air Defense building that evening. After following the raid on

radar and hearing reports of the destruction, he remarked that the

flyers must be disposed of. The next day, both Wako and Sato brought up

the idea of executing the captives. Wako remembered Sato saying that,

because more air raids on Kyushu were expected, the Air Defense Section

was going to execute the enemy flyers in their custody. Wako responded

that, subject to the approval of Yokoyama, they would execute the four

enemy flyers who were being held pending trial. Wako then spoke to

Yokoyama, noting that, given the work needed to prepare for the

expected American invasion, there was no time to try the prisoners, and

they should be executed without a trial. Yokoyama, under the impression

that Tokyo wanted the flyers killed, gave his permission. Yokoyama also

wrote to Sato and Ito, saying, "I have decided to concern myself only

with the decisive battle and hereafter do not bother me with the

problem of the flyers." Yokoyama had washed his hands of any further

dealings with the prisoners.

According to his pretrial affidavit, Wako ordered six detention barracks guards to dig a pit in the backyard of Western District Army Headquarters on June 20. Wako also informed his subordinate, Lt. Sadayoshi Murata, about the execution; the latter then attempted to contact Ito, their superior and Chief of the Legal Section. About an hour later, the four flyers from the Judicial section were brought out from their cells. Four more flyers, those under Sato's control in the Air Defense section, were also brought to the pit. All were blindfolded and had their hands tied in front. Several swords were obtained from the Legal Section. Wako then told the twenty or so assembled Japanese that, "in compliance with the Commanding General's orders, we were going to execute the plane crash survivors." One officer, Lt. Michio Ikeda of the Medical Section, volunteered himself, and Wako ordered Probationary Officer Tamotsu Onishi, since he was skilled in kendo, to assist him as a third executioner. Sato watched the proceedings from one side. The first flyer was brought to the edge of the pit and made to sit on his haunches. Wako then ritually washed one of the swords and stood behind the prisoner, slightly to the left. Raising the sword above his right shoulder with both hands, Wako brought it down on the flyer's neck. "Both the body and head fell into the pit," remembered Wako; "I washed my sword and ordered the guard to bring another flyer to the pit. I killed this flyer exactly the same way I had killed the first one." Onishi then executed a third prisoner in the same manner. In the pause that followed, Lt. Kentaro Toji, an officer attached to Western Army Headquarters, approached Sato. According to his pretrial affidavit, Toji said to Sato, "My mother was killed in the air raid on Fukuoka this morning, and I think it would be fitting that I be the one who [should] execute these American flyers." Sato told him to wait while Wako ordered Ikeda to execute the fourth flyer. Toji, after borrowing a sword from Onishi, beheaded the last four prisoners. The pit was then filled with dirt. (FOOTNOTE: Of the eight flyers, four were later identified as Robert J. Aspinall [Yayoi crash], Otto W. Baumgarten [Sanko crash], Merlin R. Calvin [Nobeoka Bay crash], and Jack V. Dengler [Nobeoka Bay crash]. Four were never identified [Two later were indentified to be McElfresh and Romines]. They came from among twelve other flyers held at Western Army Headquarters prior to June 20; Jack M. Berry [Nobeoka Bay crash], Billy J. Brown [Nango crash], John C. Colehower, Irving A. Corlias [Nobeoka Bay crash], Leon E. Czarnecki, William R. Fredericks, Edgar L. McElfresh [Sanko crash], Dale E. Plambeck, Teddy J.Poncza, Charles E. Palmer [5/27/45 Moji crash of "Tinney Anne"], Ralph S. Romines [Sanko crash], and Robert B. Williams. The other eight had already been killed during vivisection experiments at Kyushu Imperial University Medical College between May 16 and June 3, 1945. See U.S. v Kajuro Aihara et alia, file 36-527-1, RG 153.) [NOTE: See this PDF scan of an archival document of March 5, 1946 which shows some of these airmen listed as being killed by the A-bomb in Hiroshima, a ploy used by the Japanese military to cover up the vivisection atrocities.] Meanwhile, since Ito's office in the Legal Section had burned down in the bombing raid, Murata found Ito only after a lengthy search. Unwilling to interfere with what he thought was a superior's orders, Ito did not prevent the executions. He immediately realized, however, that four of the executed Americans had been named in the report sent to the War Department's Legal Section in early June. Despite having heard no reply, Ito was sure that Tokyo would want to know the results of any trial. According to Murata's testimony, Ito met with Sato and Wako and asked "how he could send such a report [about a trial] since the prisoners had already been executed without trial." Concerned about possible repercussions, Sato's Staff Section compiled a false report stating that sixteen enemy flyers were killed during the bombing of Fukuoka on June 19, 1945. A copy was delivered to the Legal Section and the original, approved by Maj. Gen. Fukushima, was sent to the War Ministry in Tokyo. As part of this cover-up, a false Legal Section report was also delivered to the War Department's Legal Section in Tokyo. (FOOTNOTE: When Murata saw the false report, he noted that sixteen flyers was too high a number. He did not know, however, of the eight flyers who had been killed at Kyushu Imperial University.) August 10 Incident Western Army Headquarters at Fukuoka received seventeen more prisoners after June 20. These included the six survivors from the B-29 lost on July 27, other bomber crews, and an assortment of navy and army fighter pilots. (FOOTNOTE: Although Imperial General Headquarters was pursuing a policy of conserving air strength, to maintain a reserve for the Ketsu-Go Operation (i.e., the decisive struggle for the homeland), the Sixth Air Army on Kyushu was authorized to "carry out strong counterattack operations vs. U.S. heavy aircraft raiding homeland," and it was these planes that attacked the B-29s over Omuta and shot down a few of the twenty-one operational bomber losses in July and August.) On August 7, a shocked Sato returned to Western Army Headquarters and reported on the devastation in Kyushu. He had traveled to Hiroshima, seen the effects of the atomic bomb, and inspected the incendiary damage at Kofu and other cities. Because of the damage and the fear of an imminent American invasion, Sato decided to execute another set of prisoners. On August 9, possibly after the Nagasaki atomic bomb attack, Sato asked Maj. Tatsuo Itezono if he would carry out the executions. Itezono was in charge of guerrilla warfare training for Western Army Headquarters. The guerrilla unit at Fukuoka was made up of officers and probationary officers who were being trained to lead guerrilla fighters against the Americans. Although the testimony is sparse, these executions seem to have been in direct retaliation for firebombing in general and the atomic bombs in particular. According to Itezono's testimony, Sato told him to bring the officers of his guerrilla section to the execution. They were to help carry out the executions, and, in order to gain experience in guerrilla weapons and warfare, they would use the sword, karate, and crossbows to kill the prisoners. Itezono was informed that a truck would leave for the site the following morning, that an officer of the Legal Section would be present, and that the investigation of the prisoners was complete. He thus assumed that the prisoners were to be executed by order of the Commanding General, when, in fact, it was on Sato's initiative. The truck carrying eight Americans, Itezono, and twenty-three other Japanese arrived near the Aburayama execution grounds in the early morning of August 10. Col. Kiyoharu Tomomori, who had been told of the executions by Itezono, arrived separately by staff car. Wako was already present because earlier that morning he had presided over the execution of a Japanese soldier convicted of destroying government property. The flyers, who were blindfolded and dressed only in shorts, were helped down from the back of the truck and placed under guard while a burial pit was dug nearby. After the Japanese soldiers were lined up in formation, Wako ordered them "not [to] speak to anyone about the execution they were about to witness, because it was a military secret." Tomomori, after receiving a salute from all present, ordered that Itezono should direct the proceedings and that those "not taking part will watch carefully and learn during the execution." Itezono asked for volunteers, and more than enough officers stepped forward. Probationary officer Osamu Satano testified that he stepped forward not because he wanted to kill a flyer but because he "did not want to be considered a coward" by his fellow officers. Each of the first four flyers was executed by a different first lieutenant. (FOOTNOTE: There is evidence that at least one probationary officer refused to execute a prisoner even when ordered to do so. The officer was not punished for this refusal.) All four prisoners were killed by sword blows, without completely severing the head. One officer did not strike hard enough and, while the dazed flyer teetered on the edge of the pit, struck again. The second stroke went deep, and the flyer fell into the pit. The fifth flyer was struck in the skull by 2d Lt. Minehiro Ohno and also did not fall. Wako counseled the probationary officer on the proper blow and, a few moments later, the second stroke cut quite deep and the flyer toppled into the pit. The sixth flyer was completely beheaded by Probationary Officer Satano. This impressed the soldiers, who commented on the clean stroke, and Tomomori personally congratulated Satano. According to the testimony of Probationary Officer Fukichi Yamamoto, the next prisoner was led to a spot about five meters from the pit and was made to kneel, Japanese fashion, facing Probationary Officer Takashi Otsuki. The officer was given a crossbow and fired twice, missing the flyer. A third arrow struck the prisoner a glancing blow on the head. A fourth shot again missed. At this point, the demonstration a failure, the flyer was led to the pit. A newly arrived soldier, Probationary Officer Masahiko Narazaki, was ordered to kill the flyer with the "Kesagiri stroke." This type of blow cut diagonally inward from the victim's shoulder. After this, the prisoner was still breathing, and Narazaki had to stab him in the heart. After a ten-minute break, it was decided the final prisoner was to be executed by karate. The flyer was first struck by two probationary officers. Several others, graduates of the Futamata training school, also demonstrated blows, striking him with their fists and kicking him in the groin. Itezono then ordered the demonstration stopped; the flyer was led to the edge of the pit, and an unidentified probationary officer killed him with one blow to the neck. Afterwards, four soldiers rearranged the bodies in the grave, covered them with a straw mat, and filled the pit with dirt. Meanwhile, according to Itezono, Tomomori pulled a small bottle from his pocket and gave Satano and the other probationary officers a drink of whiskey. Some witnesses thought the whiskey was offered because the executioners felt bad about what they had done. Others seemed to think it was a reward for volunteering. Tomomori himself said he passed around the whiskey to make the executioners "feel better." The mood conveyed by these statements implies some reluctance on the part of the participants, even though all had volunteered. After the pit was filled, Itezono called the soldiers to formation to hear a speech by Tomomori. Yamamoto remembered him saying, in effect, "The persons who were executed today were not ordinary prisoners of war. These men were enemy flyers who had burned out towns and houses," killing innocent civilians. Ohno believed Tomomori also said, "These men were enemy fighter aircraft crew members. Therefore, this execution is not contradictory to International Law. To those who participated and those who did not, this execution has been a valuable experience in the light of the coming decisive battle." Two other witnesses remembered Tomomori's comments somewhat differently. Private Masashi Yoshida, who had been guarding the truck during the executions, remembered that Tomomori ordered the soldiers to keep these executions a secret. Michio Ikeda, a corpsman assigned to the Medical Section, stated that "At the time of the execution no written sentences of death were made. Furthermore, the reasons for the execution were not explained to the American crew members... furthermore, this was an unjust and secret execution... [not] a formal courts-martial [sic] in accordance with military regulations." At 3:00 in the afternoon of August 15, 1945, a truck filled with Japanese soldiers and seventeen blindfolded and handcuffed Americans drove out the front gate of Western Army Headquarters in Fukuoka, Japan. Three hours earlier, the Japanese guards had listened to the emperor read a statement ending the Pacific war. The truck arrived at the Aburayama execution grounds at 3:30. The soldiers ordered the American prisoners, all captured pilots or flight crew, out of the truck. Weak from six weeks of poor diet and little exercise, the prisoners quietly obeyed. They were led to a neighboring field bordered with bamboo groves and made to sit in the late afternoon sun. After a brief discussion, the Japanese divided into groups and stationed themselves at four different sites around the field. The first three execution squads were led by Lt. Noboru Hashiyama, an officer attached to the headquarters unit, and lieutenants Teruo Akamine and Ichiro Maeda, both assigned to the Air Defense Section of Western Army Headquarters. Leading the fourth was a probationary officer from the Guerrilla Unit, which was made up of officers receiving guerrilla warfare training at Fukuoka. One by one, the prisoners were led to the different sites and made to sit with their legs extended out front. At one end of the field, Hashiyama beheaded the first prisoner with two strokes of his sword. Nearby, Akamine also executed a prisoner. Behind a bamboo thicket, the shouts of Maeda's squad and the probationary officers filled the air as they began executing their eight prisoners. Col. Yoshinao Sato, chief of the Air Defense and Air Intelligence Unit, along with his aide, Lt. Hiroji Nakayama, arrived just as the executions began. Hashiyama asked Sato if he would permit Nakayama, who was known as an expert on bushido, to participate. Sato ordered his aide to instruct the young officers in the correct procedure. Nakayama explained that "etiquette, according to old customs, demanded that the neck not be completely severed; this was supposed to be insulting to the person being beheaded." To demonstrate, Nakayama drew his sword and washed it in water from a bucket. Then, moving quickly toward a prisoner, he cut the man's throat from the side through the neck artery, killing the flyer at once but leaving the neck not entirely severed. Then, before the man fell to the ground, Nakayama swung the sword around and cut the flyer's neck from the front, still not entirely cleaving the head. According to Nakayama, this was "the true method of execution as I have read in books of old Japanese customs." Upon Sato's request, he executed a second prisoner in the same manner. Meanwhile, Maeda, in the bamboo grove, executed one flyer and presided over the executions of three others. To their right, still in the bamboo, the probationary officers killed the remaining prisoners. According to a second-class private, Yasuo Motomura, one of the flyers at that location was struck with "karate blows around the diaphragm. The prisoner fell down groaning with pain, but immediately tried to run away. At that instant the prisoner was cut down with a sword." Within minutes, all seventeen American prisoners lay dead upon the ground. All had been killed by sword blows to the neck. Their bodies were covered with grass mats and loaded on the truck for transportation to the crematorium. Word was also passed that all persons who participated in the executions should keep silent, clean their swords, "and see that blood or small pieces of bone had not remained on it... to be sure that no evidence of the execution remained on it." (FOOTNOTE: The main trial record is found in U.S. v Isamu Yokoyama et alia, file 36-528-1, War Crimes Branch, Case Files, 1944-49, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), Record Group 153, National Archives, Washington, D.C. For specifics on the August 15 executions, see "Review of the Staff Judge Advocate," July 17, 1949, U.S. v Kiyohara Tomomori et alia, file 36-533-l, ibid. (hereafter cited as "Review"), 33; "Review of the Staff Judge Advocate," U.S. v Suekatsu Matsuki, file 36-529-1, ibid., 1-4; "Review of the Staff Judge Advocate," U.S. v Teruo Akamine, file 36-528-1, ibid., 1--5, and "Review of the Staff Judge Advocate," U.S. v Noboru Hashiyama, file 36-530-1, ibid., 1-4. For an excellent examination of Japanese treatment of POWs on a larger scale, see Charles G. Roland, "Allied POWs, Japanese Captors and the Geneva Convention," War & Society, IX (1991), 83-101.) - - - - - - - - - - On the morning of August 15, it was announced that an Imperial Rescript would be read over the radio at noon. All the remaining officers assembled in the staff office and heard the Emperor's surrender proclamation. To some, the reaction was "a mixture of incredulity, shame, horror... many of the younger field officers found the decision impossible to reconcile with all they had been taught." The atmosphere in the Air Defense Section became angry, and, according to Sato, "people in general were too excited." Afterwards, the senior officers discussed the possibility of executing the remaining prisoners. Although clearly against the spirit of the Imperial Rescript, this idea was most likely prompted by a desire to cover up the August 10 executions by silencing witnesses. Owing to contradictory statements by Sato, Fukushima, and Maj. Tonenusuke Kusumoto, an adjutant at Western Army Headquarters, it is impossible to determine definitively who initiated the last executions. Kusumoto, however, thought Sato was relaying a lawful order. He therefore told Lt. Ichiro Maeda and the other young officers "that they were going to have to execute the remaining flyers because if they didn't the other executions would then become known." Another officer was told by Kusumoto that "There will be an execution of enemy flyers. The flyers are being executed because they are held responsible for indiscriminate bombing.... The executions are to be kept very secret." Lt. Teruo Akamine remembered Kusumoto saying that anyone interested in participating in the execution should be present later in the day. This seems to imply that the participants were volunteers. As noted earlier, by the late afternoon of August 15, 1945, all seventeen remaining prisoners had been executed. Over the next several months, in the confusion of surrender and occupation, Sato became the architect of a plot to cover up the illegal executions. The initial phase consisted of the burning and destroying of any documentation referring to the prisoners. Gen. Yokoyama, under orders from Tokyo, had already ordered that "all staff officers [were] to destroy all important papers, records, and all evidence that would reveal any reflections on the treatment of POWs. Meanwhile, Wako ordered Murata to exhume and cremate the bodies and destroy all evidence that the prisoners had been held in Fukuoka. (FOOTNOTE: The bodies were cremated in a temporary crematorium because the regular facility was too busy cremating Japanese civilians killed during bombing raids.) Months later, when American investigators began asking military units what they had done with their prisoners, Sato and Fukushima discussed various schemes for covering up the executions. These included claiming that the prisoners were killed in the Fukuoka air raid on June 19, that the prisoners died in the Hiroshima atomic bomb attack, or that they were lost in a plane crash during an attempted transfer to Tokyo. Source: "To Dispose of the Prisoners": The Japanese Executions of American Aircrew at Fukuoka, Japan, during 1945, by Timothy Lang Francis, Pacific Historical Review, Vol. LXVI, Nov. 1997, No. 4, pp. 484-486. (C) 1997 by the Pacific Coast Branch American Historical Association. The author is a historian at the Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C. "The paper is dedicated to the memory of my uncle, Frederick Allen Stearns, killed at Fukuoka, Kyushu, Japan, on either August 10 or 15, 1945." (All quotes in this paper are either from depositions submitted by the defendants immediately preceding the 1949 trials or from the trial transcripts themselves. Apparently, no contemporary Japanese Army documentation describing the events at Fukuoka survived. Unlike the case of Nazi Germany, much evidence of wartime misdeeds was destroyed before Allied forces occupied Japan.) See also by same author excerpt below on incendiary bombing of Omuta and B-29 crash of July 27, 1945. |

2. At Aburayama (Google Satellite)

Two incidents are recorded pertaining to Aburayama. The first was on August 10, 1945 (after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki). Eight airmen were taken to a wooded area next to the Aburayama Municipal Crematory (located in Hibaru), blindfolded and made to sit, and then beheaded.

From the Fall of Japan by Craig, pp. 141-143

| On August 11 [10], in Fukuoka,

one hundred miles north of the burning remains of Nagasaki, some

Japanese army officers sat in their headquarters and discussed murder.

Just recently, news of the atomic bombings had inflamed opinion against

the Americans. In Fukuoka, it occasioned a day of violence. There, the

Japanese had under their control a group of captured American B-29

crewmen who had been shot down on raids mounted from the Marianas

during the past three months. The jailers had already executed eight

fliers in formal rites carried out on the twentieth of June. Now they

were preparing to kill again.

At 8:30 A.M., a truck pulled up to the rear of Western Army District Headquarters. Thirty-two men got into the back and sat down. Eight of them were Americans. The rest were Japanese soldiers. The truck went out through the rear gate and down the road to a place called Aburayama, several miles south of Fukuoka City. In a field surrounded by dense undergrowth, the prisoners were led down from the back of the vehicle and arranged in a loose line. They were stripped to shorts or pants and forced to watch as Japanese soldiers began to dig several large holes in the ground. The Americans said nothing to each other. Shortly after 10:00 A.M., a first lieutenant from a Japanese unit training for guerrilla warfare stepped down forward and brandished a gleaming silver sword. As one of the Americans was prodded forward and forced to a kneeling position, the Japanese officer wet his finger and ran it across the sharp edge of his weapon. Then he looked down at the bowed head of the prisoner and gauged the distance. Suddenly his sword flashed in the sun and crashed against the bared neck. It cut nearly all the way through to the Adam's apple. The line of captives silently watched their comrade die. Some turned away. Others saw the body roll sideways onto the grass. A second flier was pushed forward to be killed. A third, a fourth was decapitated. The fifth one was butchered by an executioner who required two strokes to sever the head. The Japanese officers introduced a new torture on the sixth prisoner. He was brought in front of a group of spectators and held with his arms behind his back. A Japanese ran toward the American and smashed him in the stomach with the side of his hand. The flier slumped forward but was pulled upright again to receive another karate blow. Three, four times, the powerful chops to the body were repeated. When the victim did not die, his head was cut off. The seventh prisoner suffered the same cruelty from men practicing the art of killing with their bare hands. When he too survived the vicious karate, one of the officers, angered by his own failure, rushed up and kicked him in the testicles. The prisoner fell to the ground, his face contorted by nausea and pain. He pleaded, "Wait, wait," but his tormentors had no pity. He was pulled into a kneeling position while the captors debated another manner of execution. They settled on kesajiri. Another sword glinted in the sun over the bowed form and cut down through his left shoulder and into the lungs. The American died in a froth of blood. The last prisoner had seen seven men hacked to death before his eyes. His last moments were a blurred image of blood, steel slashing through skin and bones, cries of pain from his friends and shouts of glee from his enemies. Now he knew it was his turn. He was pushed into the center of the maddened group of soldiers, who made him sit down on the ground. His hands were tied behind him. Ten feet away, another officer from a guerrilla unit raised a bow and placed an arrow on it. The American watched as the Japanese pulled it back, sighted on him, and let go. The arrow came at his head and missed. Three times the officer shot at the American, and the third arrow hit him just over the left eye. Blood spurted out and down his face. Tired of the sport, his captors prodded him into the familiar kneeling position and chopped his head from his body. On the field of Aburayama, eight torsos stained the meadow grass. |

The second incident was on the day of cessation of all hostilities, August 15, 1945. Seventeen airmen were taken to Aburayama and were executed by beheading. For further information on this atrocity, see "To Dispose of the Prisoners": The Japanese Executions of American Aircrew at Fukuoka, Japan, during 1945 by Timothy Lang Francis (from The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 66, No. 4. (Nov., 1997), pp. 469-501).

a. Interrogation of Itaru Bajiri re August 10, 1945 incident

I, Itaru BAJIRI, after being duly sworn on oath to speak the truth conscientiously adding nothing or concealing nothing, testified at Legal Section Fukuoka Branch Office, Fukuoka-ken, Kyushu, Japan, on 24 September 1948, as follows:

Q. State your full name, age, and present address?

A. Itaru BAJIRI, age 31, and I live at Oita-ken, Oita-gun, Honda-mura, Oaza-shimo-handa, No. 2353.

Q. What is your present occupation?

A. I am in construction business.

Q. Are you married, if so, do you have any children?

A. Yes, I am married, and I have one daughter, age 4.

Q. Did you ever serve in the Japanese Armed Forces?

A. Yes. I served in the Japanese Army from January 1939, until the end of the war.

Q. Briefly describe your military history?

A. I was inducted into the Oita 47th Infantry Regiment, Reinforcement Unit in January 1939. In December 1940, I was transferred to Defence Section, Military Affairs Bureau of the War Department. My rank at this time was corporal. In 1941, I was transferred to General Staff Headquarters. My rank at this time was sergeant. In 1945, I was transferred to General Defence Headquarters. My rank at this time was Sergeant-Major. In May 1945, I was transferred to Western Army Headquarters. On 20 August 1945, I was demobilized from Japanese Army.

Q. According to your military history, you were at Western Army Headquarters from May 1945 until the end of the war, is that correct?

A. Yes. That is correct.

Q. What section in Western Army Headquarters were you assigned to?

A. To the Guard Section under Western Army Staff Section.

Q. What are the names of persons that worked with you in the Guard Section?

A. Staff Officer in charge of Guard Section was Lt. Col. YAKUMARU, with Maj. ITEZONO, Capt. KISHIMOTO, 2d. Lt. YAMAMOTO, 2d. Lt. SUETSUGU, Probationary Officer OHTSUKI, Sgt. OHNISHI, Sgt. UCHINO, Cpl. KAJI, and myself. That is all.

Q. Was this the total personnel towards the end of the war?

A. Yes.

Q. What were your duties at Western Army Headquarters?

A. I was a clerk concerning Special Area Defence Guards, and the National Civilian Defence Army. I believe these defence units were organized and supervised by the Army.

Q. Was the Guard Section ever known as the Guerrilla Unit at Western Army Headquarters?

A. Yes, although this was not the proper name.

Q. Were you at Western Army Headquarters between 9 August 1945 and 16 August 1945?

A. I believe I was.

Q. Did you ever take any trips while you were at Western Army Headquarters?

A. Yes. I once went to Kumamoto-shi, I believe in July, and once to Tokyo around the middle of July 1945. That is all.

Q. Have you any knowledge of Allied POWs being executed by W.A. Hdqs. personnel?

A. Yes.

Q. How many prisoners do you know of that were executed?

A. I don't know, I have never heard as to how many.

Q. Who did you hear this from?

A. From Capt. YUKINO of the Adjutant Section.

Q. What did you hear from Capt. YUKINO?

A. I do not know the exact date but I believe it was in the early part of August 1945, Capt. YUKINO came into our office and told Capt. KISHIMOTO that, "shortly there will be an execution of prisoners, and that officers may attend the execution."

Q. To what prisoners did YUKINO's statement refer to?

A. I do not know. I believe he was referring to the prisoners at Western Army Headquarters.

Q. And what prisoners were they?

A. I do not know, but I believe they were American prisoners.

Q. Why did you believe they were American prisoners?

A. Because Capt. AIHARA of the Guard Section was handling personal properties confiscated from American plane crash survivors, therefore I believe the prisoners kept at Western Army Headquarters were Americans.

Q. Did you ever see any of the prisoners at Western Army Headquarters?

A. Yes. I saw three (3) or four (4) prisoners.

Q. Describe the prisoners that you saw?

A. The prisoners that I saw were bare-footed, and wore O.D. cover-alls. They were Caucasians.

Q. When YUKINO told KISHIMOTO that, "shortly there will be an execution of the prisoners," what did KISHIMOTO say?

A. I do not remember what KISHIMOTO said.

Q. Who was in the room when YUKINO said this to KISHIMOTO?

A. Capt. KISHIMOTO, 2d. Lt. SUETSUGU, Sgt. OHNISHI, Cpl. KAJI, and myself. I believe Probationary Officer OHTSUKI was also there.

Q. Was Lt. Col. YAKUMARU or Maj. ITEZONO also there?

A. No.

Q. When did the execution occur?

A. I believe the execution occurred 2 or 3 days later. 2d. Lt. YAMAMOTO told me in the office room that he had just returned from the execution of the prisoners. That "KARATE" and bow and arrows were used.

Q. Exactly what did YAMAMOTO say to you?

A. YAMAMOTO said that there was an execution of the prisoners, I do not remember whether he said plane crash survivors or not, and that he went to the execution. The "KARATE" and Bow and Arrow was used but it was ineffective. The prisoners were beheaded. That is all I heard.

Q. Did you attend the execution?

A. No.

Q. To the best of your knowledge, who attended the execution of American prisoners in early August 1945?

A. I have heard that Capt. ONO, Probationary Officer OHTSUKI, 2d. Lt. SUETSUGU, 2d. Lt. YAMAMOTO, and several officers and Probationary Officers whom I do not know.

Q. Who did you hear this from?

A. I overheard the conversation carried on by the persons whose names I have just given.

Q. What did you hear?

A. I heard that "KARATE" and bow and arrows were tested on the prisoners, but they were ineffective. Therefore the prisoners were beheaded.

Q. Did they ever mention about their part in the execution?

A. 2d. Lt. YAMAMOTO said that he tried the "KARATE". Probationary Officer OHTSUKI said that he tried the bow and arrow. The others did not say anything.

Q. Did Capt. KISHIMOTO attend the execution?

A. I do not know. I do not remember him mentioning anything about the execution.

Q. Did KISHIMOTO have an injured foot at any time, at Western Army Headquarters?

A. Yes.

Q. Did he have the injured foot at the time the execution occurred?

A. Yes.

Q. Exactly what did you do on the day that the execution occurred?

A. I was sorting out the properties confiscated from American prisoners. I did this alone, on the lawn near the office. I did this because all of the properties confiscated were thrown into one box. I sorted this and separated the items into groups. The items I sorted were, combat knives, canteens, gun-belts, signal lights, and loose ammunition.

Q. By whose order did you do this?

A. Capt. KISHIMOTO's order.

Q. What time of the day was it when you started sorting the confiscated properties, and how long did you take to complete it?

A. I started on this at about 0900 and finished around 1030 hrs.

Q. When the officers and probationary officers under command of Maj. ITEZONO were called for assemblies, such as roll call, and orders for the day, were you present?

A. No. To the best of my knowledge there were no assemblies where the entire personnel was called. In most cases different assemblies were called for officers and enlisted personnel.

Q. Were you ever at an assembly when Maj. ITEZONO stated that "Tomorrow there will be an execution of plane crash survivors"?

A. I believe there was. I believe this assembly was after Capt. YUKINO came to our office.

Q. Then you positively know that American plane crash survivors were going to be executed by men under Maj. ITEZONO's command, the following day, is that correct?

A. Yes. That is correct.

Q. How many flyers were going to be executed?

A. I do not remember hearing how many flyers were going to be executed.

Q. Did you attend the execution?

A. No.

Q. Are you sure?

A. Yes.

Q. You have stated in your statement earlier that Capt. YUKINO of the Adjutant Section, came into your office and told Capt. KISHIMOTO that "shortly the prisoners will be executed, and that all officers may attend the execution", is that correct?

A. Yes. That is correct.

Q. Do you know Capt. YUKINO well?

A. I do not know him well, but I did see him often.

Q. Did you talk to him often?

A. I only talked to him 3 or 4 times while I was at Western Army Headquarters.

Q. Are you sure that this person was YUKINO and not mistaken for someone else?

A. I am absolutely sure that it was Capt. YUKINO.

Q. Are you sure that it was not Maj. ITEZONO?

A. Yes, I am absolutely sure.

Q. What was YUKINO's capacity at Western Army Headquarters?

A. YUKINO was one of the adjutants at Western Army Headquarters, he was in charge of personnel, secret documents, and general administration, I do not know whether he had anything to do with prisoners or not, although I heard that the Adjutant Section was responsible for them.

Q. How did YUKINO know about the execution?

A. I do not know.

Q. Was YUKINO going around to various departments in Western Army Headquarters, inviting officers to attend the execution?

A. I do not know, but I do not believe so.

Q. Was YUKINO ordered by some one to deliver the information concerning execution to Capt. KISHIMOTO?

A. I do not know under what circumstances YUKINO came to our office.

Q. Do you know anything about the 20 June 1945 execution?

A. No. All I know is about the execution in early part of August 1945, which I have stated to the best of my knowledge in my testimony.

Q. Do you understand that should you be making a false testimony under oath, you are liable to a fine and imprisonment?

A. Yes. I understand.

Q. Do you have any corrections or additions to make in your statement?

A. No.

(Signed in Japanese)

Itaru BAJIRI.

Summary of Japanese War Crime Tribunal sentencing of Japanese personnel for Vivisection and Aburayama incidents

For further insight on these atrocities, read

The

Fallen: A True Story of American

POWs and Japanese Wartime Atrocities by

Marc Landas.

Memorial Service: Held on June 20, 2021, at Aburayama Kannon in Jonan-ku, Fukuoka. See YouTube video (Japanese).

C. B-29 crashes & airmen killed

Images from the March and April 1945 editions of a magazine for Japanese children, Children of Nippon. The image on the left reads: "Shoot down the B-29!! Try to find which plane shot the B-29 down." On the right: "We shot down a B-29!"

March 1945 (18K) April 1945 (23K)

|

Locations

where B-29s & other aircraft went down in Kyushu

Special thanks to Toru Fukubayashi for his research paper from which the above material was taken; see here for a complete PDF file. See data for all Japan in his ALLIED AIRCRAFT AND AIRMEN LOST OVER THE JAPANESE MAINLAND DURING WWII. Thanks also to the researchers at this Japanese website containing data for all of Japan, including the lists of airmen. For an interesting story, see "Last B-29 mission over Japan in WWII." Also see THE LAST MISSION. |

On

incendiary

bombing raid on Omuta

and B-29 crash of July 27, 1945...

| On the morning of July 26, 1945, a light rain

fell

slowly on the seven large American air bases in the Mariana Islands.

The 314th Wing, part of the Twentieth Air Force's vast complex of

airfields, hangars, camps, ammunition dumps, and supporting facilities

on Guam, Tinian, and Saipan, was preparing for a three-group raid on

Kyushu, Japan. Since March, increasing numbers of B-29s had been

burning Japan's urban areas with incendiary attacks intended to destroy

industry and civilian morale. After June 16, with the fifty largest

cities already bombed, missions were directed against cities of

secondary importance.

The 314th Wing was directed against Omuta, a port city on Ariake Bay on the southern coast of Kyushu. Omuta had escaped serious damage in a previous raid, so the city of 177,000 was being struck again. As Omuta was classified an "urban area," the bombers carried 500-pound M17 incendiary clusters and 100-pound M47 incendiary bombs. The 132 planes in the wing carried a total of 810 tons of bombs that were intended to drop on the small downtown area to create "maximum compressibility over the target." Because of the high proportion of wooden construction in Japanese cities, "maximum compressibility" meant the creation of a mini-firestorm. (FOOTNOTE: The M17s, fused to open and spread burning fuel at 5,000 feet, were designed to start fires over the whole area, while the M47s, with an impact fuse, were designed to intensify damage, spread debris, and discourage fire fighting. The fires, sucking in oxygen from the perimeter of the city, would then grow large enough to destroy the commercial, residential, and industrial sectors, killing large numbers of civilians in the process.) For one of the planes in the 314th Wing, #42--94098 of the 28th Squadron, 19th Bombardment Group, this mission was only its fourth over Japan. The crew was still relatively green, having arrived in late June and having bombed Hiratsuka, a city southwest of Tokyo, on July 17 and two other cities by July 23. (FOOTNOTE: The crew was 1st Lt. James E. Hewitt, Pilot/Commander; 1st Lt. James W. Gothie, Bombardier; 2nd Lt. Wayne Whitley, Radar Officer; F/0 Charles S. Appleby, Navigator; F/0 Gerald E. Boleyn, Copilot; T/Sgt. William N. Andrews, Radio Operator; S/Sgt. Ben Thornton, Flight Engineer; Cpl. Robert J. Zancker, Central Fire Control; Cpl. Frederick A. Stearns, Tailgunner; Cpl. Martin W. O'Brien, Jr., Side Gunner; and Cpl. Robert A. Sawdye, Gunner. The observer, Capt. Louis W. Nelson, was a veteran bombardier who had completed twenty-five missions in Europe and went on this flight to assist Gothie. See "Testimony of Darrell O. Does," enclosed in U.S. v Tomomori.) Crew of B-29 downed in Yokoyama,

Yame-gun (Click on image

for 121K enlargement) They seemed unconcerned about the widespread damage their bombs caused on the ground. In a letter dated July 10, Frederick A. Stearns, the plane's tailgunner, wrote that Strategic Bombing Study reports from Europe had concluded that German industry, by dispersing operations, had managed to avoid collapse until the end of the war. Presumably the Japanese were doing the same. The solution for Japan, he believed, was to concentrate on a "smaller target area [since with] the Jap's [sic] feudal system of extensive home manufacturing we can't help but cripple their war effort as long as the bombs fall anywhere within their cities." The aircrews believed, as did the Twentieth Air Force planners, that any damage to cities had to help the war effort. In the early evening of July 26, the 19th Bombardment Group's planes took off from North Field, Guam. Two planes aborted their flight on the airstrip owing to mechanical trouble, so only 130 bombers, with one weather aircraft and one "Superdumbo" (rescue assistance aircraft), began the seven-hour flight to Omuta. To fill the hours the crew slept, read newspapers, played gin rummy, and listened to the news and music from home on Saipan radio. After four hours at 20,000 feet, the formation passed over the emergency airbase and "glorified gas station" of Iwo Jima. Three hours later the stream of planes began the approach to Omuta. The first bombers arrived over the target at 12:45 A.M. local time on July 27 and began dropping their incendiary bombs. Japanese air defense fighters had concentrated over Omuta and, over the next forty-five minutes, nine confirmed fighter attacks heavily damaged seven of the bombers and caused five to jettison their bombs. In the cloudy haze over Omuta, with several large fires sending smoke plumes to 18,000 feet, the aircrews spotted numerous tracer trails, explosions, burning debris, and glowing fireballs in the sky around them. By 1:32 A.M. local time the last B-29s dropped their ordnance and turned for the long flight home. Over a third of Omuta was destroyed or in flames, leaving an unknown number of dead, wounded, and homeless Japanese civilians. Of the 130 aircraft of the 314th Wing on the mission, 105 returned to North Field, seven diverted to Saipan and Tinian, and seventeen made emergency landings on Iwo Jima. Only one did not return. During the mission debriefing, witnesses reported that a B-29 turned away from Omuta and began heading home about 12:50 A.M. With one engine on fire, the bomber slowly lost altitude. Witnesses saw the flames flicker off and on until the aircraft crossed the coast, perhaps ten miles past the target, and descended into a cloud bank. The fire lit up the clouds and caused a huge glow in the sky. Tracer fire was spotted through breaks in the clouds, and Japanese fighters were seen attacking the aircraft with machine guns. At 12:58 A.M., more tracers were spotted, and the B-29, by now flying level, suddenly disintegrated into two or three flaming pieces. No parachutes were spotted. Thirty minutes later five rafts were spotted in Ariake Bay. Despite the rafts, it seemed that this aircrew had met a fate not unlike the thousands of others lost over Europe or Japan. Relatives were notified of "missing in action" (MIA) status on August 11, 1945, and on April 23, 1946, owing to the lack of any contrary evidence, the crew was officially listed as "killed in action" (KIA). A few members of that crew, however, survived the crash despite the confusion that must have reigned amid the flames and explosions of the stricken B-29. (FOOTNOTE: Six of the crew managed to parachute to earth. These were Hewitt, Appleby, Whitely, Thornton, Stearns, and Nelson.) They were captured and turned over to Western Army Headquarters, the administrative component of 16th Area Army, in Fukuoka, Japan. (FOOTNOTE: Western Army Headquarters responsibilities included all of Kyushu and south to 30° N, west to include the Tsushima, Iki, and Goto Islands, and north to include Toyoura-gun, Yamaguchi-ken, and Honshu. The plane crashed at 33° 16' N by 130° 42' E [NOTE: These coordinates are Yokoyama, Yame-gun; see Haraguchi testimony]. See "Intelligence Briefing," 28, enclosed in U.S. v Isamu.) Source: "To Dispose of the Prisoners": The Japanese Executions of American Aircrew at Fukuoka, Japan, during 1945, by Timothy Lang Francis, Pacific Historical Review, Vol. LXVI, Nov. 1997, No. 4, pp. 473-476. (C) 1997 by the Pacific Coast Branch American Historical Association. See also by same author above excerpt on beheading incidents of June 20, August 10 and August 15. |

1. Interrogation of Gunji Haraguchi re B-29 crash in Yokoyama, Yame-gun

I, Gunji HARAGUCHI, after being sworn to speak the truth, conscientiously, adding nothing or concealing anything whatsoever, testified at Kitagawachi, Yame-gun, Fukuoka-ken, Kyushu, Japan, on 1 December, 1947, as follows:

Q. State your full name, age, and present address?

A. My name is Gunji HARAGUCHI, age 53, and my address is Fukuoka-ken, Yame-gun, Kitagawachi-mura, Oaza Kukihara, No. 1285-2.

Q. What is your present occupation?

A. I am a farmer.

Q. Briefly describe your activities during the war?

A. During the war I lived at my present home, and I was a farmer. On 20 May 1945 I was drafted into the Japanese Army at Fukuoka Area Headquarters, in Fukuoka City. I was assigned to the Kuroki machi Keibitai Headquarters and was ordered to head a detachment stationed in Kitagawachi Village. I was a second lieutenant at that time and my duties were to draft persons from the Kitagawachi Village area and to train them. I was assisted by Sgt. Maj. KONISHI and Cpl. YAMAMOTO. The duties of the Keibitai Guard Unit was to train civilians as guard unit members, to make security checks and to perform as a combat unit in case of enemy invasion.

Q. Where is Sgt. Maj. KONISHI at present time?

A. He is living at Hoshino-mura, Yame-gun, Fukuoka-ken.

Q. Where is Cpl. YAMAMOTO at the present time?

A. He is living at Kitagawachi-mura, Yame-gun.

Q. What were KONISHI'S and YAMAMOTO's duties?

A. They both assisted in training the Guard Unit members.

Q. State everything you know concerning any Allied plane crashes?

A. The only Allied plane crash that I know of was that of a B-29 which crashed at Kyura [Kiura], Yokoyama-mura, Yame-gun, in the early morning of 27 July 1945. I was first informed about this plane crash at about 0300 hours by Cpl. YAMAMOTO. YAMAMOTO told me that an enemy plane had crashed and that one survivor was already captured. I asked YAMAMOTO where the survivor was but he did not know where he was being held. YAMAMOTO and I then walked along the main street in Kitagawachi and noticed a group of people gathered in front of the Kyushu Electric Company's Quarters. At this time I learned that the plane crash survivor was being held inside that building. At this time a Kempei Tai, Sgt. Major, asked me to loan them my office because the room where the flyer was held was too small. My office was in the Kitagawachi Primary School. I consented and the plane crash survivor was soon taken to my office. While the flyer was being questioned by the Kempei Tai I went outside and waited.

Around 0800 hours on the same day another plane crash survivor, who was captured at Kyura, Yokoyama-mura, was brought to my office. Then around 1100 hours another captured flyer was brought into my office. After dinner I went to the scene of the crash. While at the scene, I did not see any dead bodies of the crew. I returned to my office around 1900 hours and at that time learned that one more flyer had been captured and taken to my office while I was absent. Also I was told by the members of the Keibi Tai and the civil police, I have forgotten their names, that the first four flyers captured had already been taken to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters from my office at Kitagawachi by the members of the Kempei Tai. As the fifth captured flyer was brought to my office, after the Kempei Tai had taken the other four captured flyers to Kurume, I contacted the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters by phone and asked what should be done with the fifth captured flyer. Someone at the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters told me that he would contact the Kuroki Machi Keibitai Headquarters and tell them to take the captured flyer to their headquarters. I then called up the Kuroki Machi Keibitai Headquarters and told them what I was told by the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters. I was told by someone at that Headquarters that they would immediately come after the captured flyer.

At about 2000 hours, a member of the Kuroki Machi Keibitai and a civil police officer arrived at my office with an automobile and took the flyer to the Keibitai Headquarters at Kuroki Machi. I do not know the names of the persons that took this flyer to Kuroki Machi. The following morning about 0800 I was told by some one from the Kuroki Machi Keibitai Headquarters that the last captured flyer was taken to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters from the Kuroki Machi Keibitai Headquarters by Kempei Tai members from Kurume.

On about 29 July 1945, I was told that a plane crash survivor had resisted being captured. I immediately went to the scene but when I arrived, the plane crash survivor had been killed. He was laying face down; hence I can not identify him.

On about 6 or 7 August 1945 another flyer was captured. This time at Yokoyama-mura by students of the Military Academy. He was also taken to my office.

Then around 7 or 8 August 1945 another flyer was captured at Yokoyama-mura and brought to my office. The last two captured flyers were taken from my office to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters by Cpl. AKASHI and Superior Private MUTA. This is all I know concerning the seven captured flyers and their disposition.

Q. Were all of the captured flyers taken to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters?

A. I heard from some one, I cannot recall their names, that the first four captured flyers were taken to Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters from my office by a Kempei Tai Sgt. Major, and six other Kempei Tai members, on 27 July 1945. I also heard from some one from the Kuroki Machi Keibitai Headquarters that the fifth flyer was taken from Kuroki Machi to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters on 28 July 1945. Cpl. AKASHI told me that he was going to take the sixth and seventh captured flyer from my office to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters.

Q. How many plane crash survivors were captured in your area?

A. A total of seven. I heard a rumor from some one that the first flyer was captured on 27 July 1945 on the road near Kyura Village by the members of the Yokoyama-mura Fire Brigade, and was brought to my office in Kitagawachi. According to the rumor I heard from someone that the second and third flyers were captured, on the same date, in the immediate vicinity of Ohira Mountain, where the plane crashed. I do not know who captured these two flyers. These flyers were also brought to my office. The fourth flyer was captured and brought to my office on the same date and taken to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters along with the other three captured flyers by Kempei Tai Sgt. Maj., I do not know where and by whom this fourth flyer was captured, and I did not see him. I heard a rumor from some one from Okubo Village that the fifth flyer was captured inside of the Okubo Village Primary School by the principal of that school on 27 July 1945. This captured flyer was brought to my office by the students of the Military Academy, guarded by a policeman named KURODA, and myself. This captured flyer was taken from my office to the Kuroki Machi Keibitai Headquarters on the same date by a member of the Keibi Tai Headquarters and a civil police from Kuroki Police Station.

The following day, 28 July 1945, I heard that this flyer was taken to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters from Kuroki Machi Keibitai Headquarters by a member of the Kurume Kempei Tai. On 6-7 August 1945, I heard from one of the students of the Military Academy, that captured and brought the sixth flyer to my office, that this flyer was captured near Iwashita, Kamiyokoyama-mura, on 6 or 7 August 1945. This flyer was taken from my office to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters on the same day by Cpl. AKASHI. I heard a rumor that the seventh flyer was captured in one of the villager's home at Hotokeo, Shimo Yokoyama-mura by the residents of the village, on 7 or 8 August 1945. I do not remember who brought this flyer to my office but he was taken from my office the same day to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters by Cpl. AKASHI. I also heard a rumor that two plane crash survivors were captured at Kami-hirokawa village. I do not know when these flyers were captured. This is all that I have heard or know concerning the B-29 crash at Yokoyama-mura.

Q. Were the two flyers that were captured at Kamihirokawa Village crewmembers of the B-29 that crashed at Yokoyama-mura on 27 July 1945?

A. I believe they were because it was soon after the plane crash that I heard about these two men being captured.

Q. Did you see the two flyers captured at Kami Hirokawa Village?

A. No.

Q. You have previously stated that a total of seven plane crash survivors were captured in your area. Is that correct?

A. Yes.

Q. How many of these plane crash survivors did you see?

A. I saw the six plane crash survivors that were brought to my office and the one that had been killed while resisting capture; making a total of seven.

Q. Did you closely see all of the six flyers?

A. Yes, I saw them from about three meters away.

Q. When you saw these men were any of them injured or ill?

A. I did not notice any of them being injured or appearing ill.

Q. All of the plane crash survivors, that you saw, appeared to be in good health. Is that correct?

A. Yes.

Q. How were they dressed?

A. I do not remember exactly what they wore, but some were wearing olive drab clothing and some were wearing khaki colored clothing. They were dressed differently.

Q. Were they Americans?

A. I believe they were.

Q. Why do you believe that?

A. The plane crash survivors were Caucasians and it was common knowledge that B-29s were American planes. From this I deducted that these captured flyers were Americans.

Q. Were they blindfolded when you saw them?

A. They were blindfolded until they were taken to my office, then their blindfolds were removed.

Q. As close as possible, describe each of the persons that you saw?

A. The first captured flyer was about 5 ft. 8 in. tall, and slender. He had bluish eyes and light brown hair and light complexion. I did not notice any scars or identification marks. The second flyer was about 6 ft. tall and well built. He had dark brown hair. I did not notice any identification marks or scars. This is all I know about this man. I do not recall what the third flyer looked like. The fourth flyer was about 5 ft. 7 in. tall and slender. This flyer had long thin face. He had bluish eyes and brown hair. I did not observe any scars or identification marks. The fifth flyer was about 5 ft. 8 in. tall and very well built. He had brown hair and a round face. I did not observe any scars or identification marks. The sixth flyer was about 5 ft. 6 in. tall and medium build. He had brown hair. I did not see any scars or identification marks. This is all I know concerning the description of the captured flyers I have seen.

Q. You have just seen the photographs of James E. HEWITT, Gerald E. BOLEYN, Wayne WHITELY, Ben THORNTON, William N. ANDREWS, Frederick A. STEARNS, Martin O'BRIEN Jr., Robert R. SAWDYE, and Louis W. NELSON. These persons were crewmembers of a B-29 which is believed to have crashed near Yokoyama-mura on 27 July 1945. Do you recall if any of these persons were among the prisoners that were captured and brought to your office and later taken to the Kurume Kempei Tai Headquarters?

A. I can not say for sure, but I believe that Ben THORNTON was among those prisoners captured. I will sign my signature on the reverse side of the photograph of Ben THORNTON. Judging from the photograph I also believe that Robert R. SAWDYE was among the captured prisoners and will sign my name on the reverse side of his photograph. Judging from the photograph I also believe that Louis W. NELSON was among the prisoners captured and I will also sign my name on the reverse side of this photograph.

Q. Did you ever hear of any of these captured flyers being mistreated?

A. No.

Q. Do you have anything to add to this statement?

A. No.

(Signed)

Gunji Haraguchi

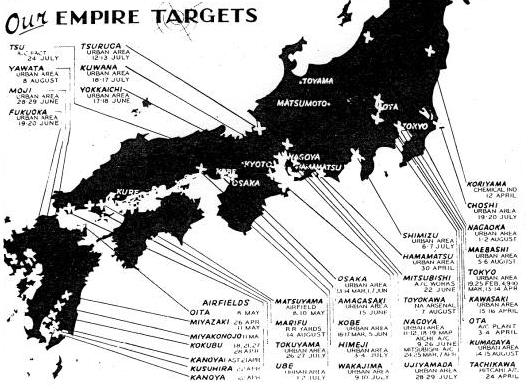

2. Air Strikes against Fukuoka & Kyushu

a. Fukuoka

8/5/44 ? (Date from Japanese pictorial on Fukuoka bombings)

11/11/44 ? (Date from Japanese pictorial on Fukuoka bombings)

5/26-27/45 Fukuoka waters mined (Mission 184)

6/7-8/45 Fukuoka waters mined (Mission 190)

6/15-16/45 Fukuoka waters mined (Mission 204)

6/18/45 ? (Date from Japanese pictorial on Fukuoka bombings)

6/19/45 Incendiary bombing of Fukuoka (Mission 211)

6/23-24/45 Fukuoka harbor mined; Hakata, Itazuke, Saitozaki Airfields bombed by P-47s (Mission 221)

7/3/45 P-51s destroy floatplanes (5th AF first mission)

7/13-14/45 Fukuoka waters mined (Mission 268)

7/27-28/45 Fukuoka waters mined (Mission 296)

7/29-30/45 Fukuoka waters mined (Mission 304)

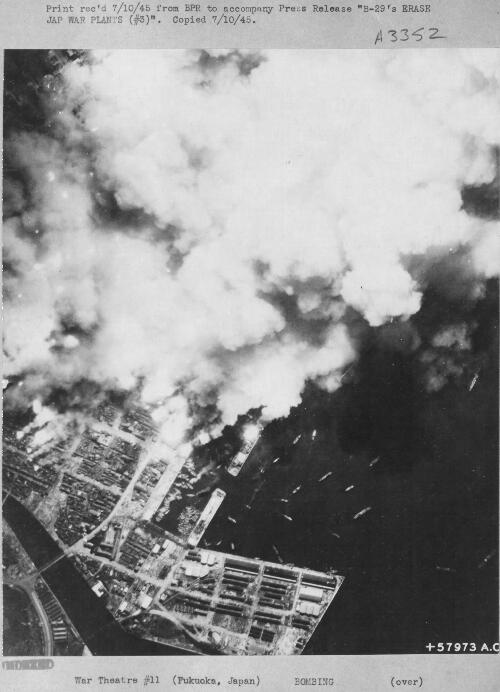

"B-29's ERASE JAP WAR PLANTS (#3.) -- The highly important industrial

city

of

Fukuoka, located on the northwest coast of Kyushu Island, burns during

a

fire raid

by 20th Air Force B-29's. Fukuoka is one of the most important port

cities

in trade

between Korea and Kyushu and contains extensive harbor and warehouse

facilities.

20 June 1945."

Target Information Sheet on Fukuoka and Mission 211 Summary

TARGET INFORMATION SHEET

NOT TO BE TAKEN INTO THE AIR ON COMBAT MISSIONS

TARGET: Fukuoka Urban Industrial Area

OBJECTIVE AREA: 90. 35-KURUME FUKUOKA URBAN INDUSTRIAL AREA

Latitude: 33° 36' N

Longitude: 130° 25' E

Elevation: Sea Level

1. SUMMARY COMMENT

Fukuoka is the commercial and administrative center for the adjoining coastal plain in northern Kyushu. Its port receives a large amount of the shipping from Korea, and a major branch of the Kyushu RR runs through the city. A number of important industries are located within the area of and adjoining the city.

2. LOCATION AND IDENTIFICATION

Fukuoka Bay is in the NW section of Kyushu, 35 miles SW of Moji and Shimonoseki Straits. The bay is approximately 12 miles across at its widest part and is shaped roughly like a shoe, with the City of Fukuoka at the position of the sole. Hills rise to 1000 ft. in the vicinity of the city and to 3500 ft. a few miles south of the city. From the NE corner of the bay a narrow arm of land extends more than halfway across the mouth of the bay, forming the top or instep of the shoe-like shape. On this arm are two airfields and several small industries.

3. TARGET DESCRIPTION

The City of Fukuoka is crescent shaped, extending for about 7 miles along the coast and from 1 to 2 miles inland. The north side of the city follows the harbor while the south side is bounded by abrupt hills. The city had a population 323,000 in 1940 and has probably grown since then, due to the increase in shipping from Korea and the development of new industries. It has a population density of about 40,000 per square mile in the congested area of the city proper.

The buildings are predominantly the single-story, tile-roof, wood-frame type that is so common in Japan. However, since a large part of the city is new and because it is a university town, it resembles in layout one of our own cities more than the ordinary Japanese hodge-podge urban industrial area. The usual heavy congestion is relieved by the three following areas: (1) a fortress in the west-central part of the city covering 200 acres and surrounded by a moat; (2) a park in the west section; (3) the university campus which extends for 2 miles along the coast of the northern section. The commercial and administrative section of Fukuoka, which serves Northern Kyushu as well as the city itself, is located in the center of the city.

Fukuoka is cut by seven canals or rivers large enough to serve as fire-breaks. However, several of the canals are close together, thereby isolating only small sections and leaving three major sections without firebreaks. These major sections are: (1) from the Ishido River, north; (2) between the Ishido River and the Naka River; (3) from the Naka River, southwest. Some of the larger industrial plants reported in Fukuoka are naval ordnance, rubber tire and shoe manufacture, heavy machinery and railroad shops.

4. IMPORTANCE

Numerous industries are located in and around Fukuoka, including two iron works producing naval ordnance, and a rubber company estimated to be producing 700 tires daily. Some textile mills and a number of warehouses are also located here.

The city is a funnel for all types of transportation. Kyushu main highway runs through the city, the harbor receives a large part of the shipping from Korea, and a major branch of the Kyushu RR runs through town with the Hakata Yards, Target 1270, serving it.

It is also important as the administrative center for the surrounding coastal plain, containing a large number of government buildings.

A list of targets located in the city proper follows:

1238 -- Watanabe Iron Works -- Important producer of

naval

ordnance.

1255 -- Hakata Harbor -- Receives large amount of shipping from Korea.

1270 -- Hakata RR Station -- Important station and yards on one of

major

Kyushu lines.

Spinning Mill

Optical Industry

Gas Company

A list of targets adjacent to the city follows:

1872 -- Showa Iron Works -- Producer of Naval ordnance.

1265 -- Nippon Rubber Co. -- Produces 700 tires and 1500 pr. shoes

daily.

1873 -- Tatara Machinery Works -- Produces coal mining machinery.

1237 -- NAJIMA SEAPLANE BASE -- 9 hangars and 12 shops at the base.

664 -- NAJIMA STEAM POWER PLANT -- 60,000 KW of 60-cycle.

Target map of Fukuoka -- August

1, 1945

Target map of Fukuoka -- August

1, 1945

(Click on image for 99K

enlargement)

See also aerial photo of Hakata Harbor targets (May 9, 1945)

Besides the destruction of a good deal of industry, an incendiary attack on Fukuoka should destroy or disrupt important regional administrative and governmental facilities. It should also post another problem for the already over-burdened Kyushu transportation system, and create a serious housing problem for governmental and industrial workers in the area.

5. AIMING POINTS

Aiming points will be specified in the Field Order.

22 June 1945.

Target Section, A-2 XXI Bomber Command

MISSION SUMMARY Mission Number 211

28 June 1945

1. Date: 19 June 1945

2. Target. Fukuoka Urban Area (90.35)

3. Participating Units: 73rd and 313th Bombardment Wings

4. Number A/C Airborne: 237

5. % A/C Bombing Primary: 92.82% (221 primary and 2 opportunity)

6. Type of Bombs and Fuzes: E-46 and E-36, 500 lb. incendiary clusters set to open 2500' above target, and AN-M47A2 incendiary bombs with instantaneous nose. [See above article for description of incendiary bombs.]

7. Tons of Bombs Dropped: 1525 tons on primary and 13.3 tons on opportunity.

8. Time Over Primary: 0011K -- 0153K

9. Altitude of Attack: 9000 -- 10,000 feet

10. Weather Over Target: 1/10-3/10

11. Total A/C Lost: 0

12. Resume of Mission: 73rd Wing strike photos showed good results, with numerous fires in the built up area of the city. 1.3 sq. miles destroyed (20%) of built up area. Medium and heavy A/A, meager to moderate and generally inaccurate. Twelve E/A sighted made 4 attacks. Ten B-29's landed at Iwo Jima. Fourteen B-29's were non-effective. Average bomb load: 14,399 lbs. Average fuel reserve: 717 gallons.

From: THE ARMY AIR FORCES IN WORLD WAR II, Volume Five

Data on aerial recon for targeting purposes by the 3rd Photo Reconnaissance Squadron, from March 1945

Targeting intel re Fukuoka gathered from interrogations of Japanese POWs, May 6, 1945 (Report dated June 18, 1945)

Aerial photo showing bombed areas in Fukuoka (Fukuoka City Damage Assessment Report, June 19-20, 1945) and Damage Assessment Report, June 29, 1945

Photo showing

devastation of downtown Fukuoka,

Oct. 2, 1945 (See May

1945 aerial

photo for comparison)

See also this photo collection of underground factories, namely in department store basements. Many other buildings such as schools were even used for the war effort.

Fukuoka: Targeted for A-bomb? Per an interview of a mobilized student worker in Fukuoka after the war:

b. Kyushu

This file has a lot of info on air strikes against Japan plus some other trivia. Note references to KYUSHU with target cities and sites mentioned. Fukuoka was strafed numerous times: ASAF History

For an interesting look at US bombing strategy in the Pacific during WWII, see United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Summary Report, (Pacific War) Washington, D.C., 1 July 1946.

An excellent site for a chronology of B-29 missions against Japan including air crashes --> 56 Years Ago, April 1944. Of special interest are the comments from some of the actual crewmembers aboard the B-29s. Visit here for a very full list of links on B-29s and crewmen stories, especially the America's War Against Japan section. Click here for a large map of destruction percentages of Japanese cities.

Photo-packed website for the 9th Bomb Group (1st, 5th, & 99th Squadrons) of the 20th Air Force

Kyushu Airfield Raids of the 39th Bomb Group, with pics of Kanoya and Oita airfield targets

444th Bomb Group photos of bombing of Yahata, August 20, 1944

D. Bataan Death March

April is a month to remember. Bataan fell on April 9, 1942, and the largest contingent of American servicemembers were captured by the Japanese -- nearly 10,000 Americans and more than 62,000 Philippines Scouts, Army and Constabulary Forces. Of these, 650 Americans and between 5,000 and 10,000 Filipinos lost their lives during the infamous 100-mile-long Bataan Death March, "the worst single atrocity committed against Americans" (see Daws, pp. 73~83). April 9th is now National Former Prisoner of War Recognition Day.

1. Death March Tales by Ray Thompson

Ray died on April 26, 1998. He was the first ex-POW I contacted by e-mail (thanks to Dick Murphey in Phoenix) and from whom I received my first bit of info on Camp #1 -- the Gibbs Report. It is said that WWII veterans are dying at a rate of 10 per day.

2. Bataan by George Idlett

I've been corresponding with George "Doug" Idlett for over 3 years. He was at POW Camp 5B in Niigata. He sent me an assortment of messages he wrote describing his experiences in Bataan, including the Death March: "I cannot possibly tell all that happened on the Death March, but I will say that whatever you may have read in many other books, it really happened. I have never read anything that I thought was untrue. I saw enough to know that it did or could have happened."

3. My Hitch in Hell by Lester Tenney

This is an excellent book -- a must-read. See Books & Videos. For more on Tenney, see Tenney's lawsuit. Visit also his homepage.

VI. Deaths, Burials & Cremations

List of Deceased

The death roster shows a total of 154 American, British, Dutch and Australian names. The DATE OF DEATH is recorded with the Japanese year of Showa first, then the month and day; hence, "20.2.24" would be Showa 20 (1945), February 24. For Australian and British POW searches, there are excellent search engines at the Australian War Memorial site and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Memorandums re 1st Fukuoka Army Hospital and Shime Crematorium

I have yet to find all of the photographs mentioned below. They could be somewhere in other Fukuoka files at the National Archives. I wish I knew where.

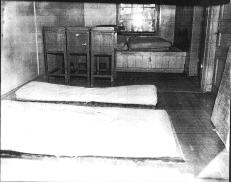

Hospital room where POWs were kept

Hospital room where POWs were kept

I, ROBERT E. HUMPHREYS, certify that the above photograph was taken in my presence, on or about 22 December, 1945, at the 1st Fukuoka Army Hospital, Fukuoka, Kyushu, Japan, and that it accurately represents the room where POW from that camp were housed during convalescence, as it appeared on that date.

(signed)

ROBERT E. HUMPHREYS

Investigating Officer

Legal Section, GHQ, SCAP

TEAM 4

INVESTIGATION DIVISION

LEGAL SECTION, GHQ, SCAP, TOKYO

Fukuoka, Japan

MEMORANDUM: 9 January, 1946

SUBJECT: Captions for Pictures taken at the 1st Fukuoka Army Hospital, and the Shime-machi Crematorium

TO: Lt. Col. Richard E. Rudisill, Chief, Investigation Division

Herewith submitted is a list of the captions of the pictures taken at POW Camp 1, Fukuoka-Ken, Fukuoka-Shi, Hakozaki-Cho, Shindate, with respect to the 1st Fukuoka Army Hospital where the prisoners from Camp 1 from both Hakozaki and Mushiroda were sent, and of the crematorium at Shime-machi, Fukuoka-Ken where most of the POW dead were sent for cremation. [See here for photo of similar crematory in Moji (9K)]

One pack---four pictures---

Picture No.

1) Room where most of the convalescent POW were kept

2) Operating room of the Hospital

3) No good---poor exposure

4) Interior of crematory at Shime-Machi, with T/4 Taro Shimomura

5) Exterior view of crematory.

6)-12) Un-exposed.

(signed)

CHARLES V. RAMEY, 1st. Lt. CE

Investigating Officer

Legal Section, GHQ, SCAP

VII. The Hellships

Most POWs who were at Camp #1 arrived on a "hellship," so named because of the terrible conditions on board and the intense suffering those conditions brought about. Daws has a very good chapter on these "slave ships." Unjust Enrichment by Holmes has a list of all the POW transports and the Japanese companies that owned them (Appendices B - D). Read also her chapter on "Voyages in Hell," from which comes this excerpt:

Official Japanese records tell a grim story: of 55,279 Allied POWs transported by sea, 10,853 drowned, including 3,632 Americans. At least 500 perished at sea from disease and thirst....The destination of 90 percent of those vessels was Japan.

Three-quarters of all POW shipments came through the northern Kyushu port of Moji. A very moving documentary to watch is Sleep My Sons: The Story of the Arisan Maru. The greatest transport ship disaster in history is the sinking of the Junyo Maru -- only 15 survived out of 5,655 American, Australian, British, Dutch, Indonesian POWs and Javanese laborers. By comparison, 1107 sailors and marines died when the USS Arizona was sunk at Pearl Harbor.

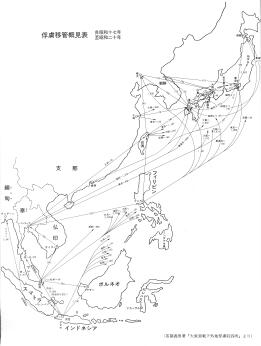

Hellship Routes

(Click for larger image, in Japanese)

The Experience

Grim facts about the transport ships...

| According to Japanese figures, of the 50,000 POWs

they

shipped, 10,800 died at sea. Going by Allied figures, more Americans

died in the sinking of the Arisan Maru than died in the weeks of the

death march out of Bataan, or in the months at Camp O'Donnell, which

were the two worst sustained atrocities committed by the Japanese

against Americans. More Dutchmen died in the sinking of the Jun'yo Maru

than in a year on the Burma-Siam railroad. The total deaths of all

nationalities on the railroad added up to the war's biggest sustained

Japanese atrocity against Allied POWs. Total deaths of all

nationalities at sea were second in number only to total deaths on the

railroad. Of all POWs who died in the Pacific war, one in every three

was killed on the water by friendly fire.

Then there was the Oryokko Maru [Oryoku-maru], the POW transport with the highest number of officers in the holds, more than a thousand, more than one in four of them field grade, and by far the highest proportion of officers to enlisted men, two to one. Yet of all ships, the Oryokko Maru was the one where the worst, most uncontrollable madness broke out, and broke out earliest, starting on the very first night and turning into killing by the second night. More than a thousand American officers could not, or at any rate did not, summon up discipline enough to stop Americans from killing each other. [See Schwartz affidavit] Was it simply that the Oryokko Maru had the absolute worst level of unbearable heat, the worst lack of water, the worst lack of oxygen, prisoners in the worst shape when they were loaded aboard, and the worst stress from being attacked? In other words, was everything simply over the human physical edge? Who can say? No one could possibly have been keeping exact figures on nutritional and health status, ounces of water per man per day, maximum temperature in degrees Fahrenheit, and the relativities of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the air, in every hold of every POW transport. Short of verifiable and verified facts, and conceding that neither Unit 731 nor anyone else set up those prisoner transports as controlled experiments in national behavior, it does appear that POWs of all nationalities were subjected to essentially the same dreadful stresses in the holds. Yet only Americans killed each other. [For a possible explanation for these killings, see Fossey affidavit.] --- Gavan Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese |

The Brazil-maru

(Click on image to enlarge)

The Brazil-maru

(Click on image to enlarge)

ORYOKU MARUAbout the voyage of the Oryoku Maru, there seems to be a misunderstanding because of a difference in the shipping lists. Perhaps this will explain it a bit clearer: The Oryoku Maru was a 7,862 ton cargo ship that departed Manila on 13 December 1944 with the following lists of passengers: 1,619 POWs On 14 December it was bombed and strafed by planes from the US carrier Hornet at 0300 Hours. Result: 50 dead; then after dawn the Oryoku Maru was sunk by another bomb. Many of the POWs were shot and died while trying to swim toward shore: 1,333 Made it to the beach On 20 & 21 December, survivors were trucked to San Fernando: ....-26 Dead Of these, 1,070 were placed aboard the Enoura Maru and 286 on the Brazil Maru. 16 died on the Enoura Maru and 5 died on the Brazil Maru. New Year's Eve was at Takao and 6 more died on the Brazil Maru. On 6 January 1945 all of the remaining POWs were moved to the Enoura Maru in Takao Harbor. The Enoura Maru was bombed, a bomb hit the hold and killed about another 300. About 900 POWs remained and they were moved back to the Brazil Maru. On the 14th of January 1946 the Brazil Maru was underway as part of a convoy bound for Japan. Another 15 died before sailing and about 40 POWs died daily during the 18 day voyage from Formosa to Moji, Kyushu, Japan. At Moji, there were only 450 survivors from the original 1,619 POWs, which tells us that 1,169 POWs were murdered in transport by the Japanese!!! Wm. E. Braye View design diagrams of these ships: Oryoku-maru - Enoura-maru - Brazil-maru |

From the Cooper Report comes a very heart-wrenching account, The Death Cruise from Manila to Japan, in which Col. Cooper describes life and death aboard the Oryoku-maru, the Enoura-maru and the Brazil-maru. Read also the George Weller dispatches about the Cruise of Death as they appeared in the Chicago Daily News, November 1945. See more in-depth article here in the San Francisco Chronicle (to be transcribed eventually).

For more, read the Schwartz affidavit. See also the Shreve Diary (Shreve was one of the American officers on board) from which I take this short excerpt:

When I finally reached the deck the air was so fresh in comparison to the hold that you were really overcome, simply by the amount of oxygen which you could take into your lungs. Several of the men fainted when they first came out into the fresh air.

Another file, The Oryoku-maru Story, a trial document from the Tokyo War Crimes Trials, was found on the Internet http://www.oryokumaruonline.org/oryoku_maru_story.html. This is an excellent website for further information.