SPEECH OF DILLON S. MYER

To be delivered July 27, 1962

PIONEER BANQUET

17th Biennial National Convention

JAPANESE AMERICAN CITIZENS LEAGUE

Olympic Hotel, Seattle, Washington

-oOo-

To be delivered July 27, 1962

PIONEER BANQUET

17th Biennial National Convention

JAPANESE AMERICAN CITIZENS LEAGUE

Olympic Hotel, Seattle, Washington

-oOo-

It is indeed pleasant to be associated with my Issei and Nisei friends again. I am greatly complimented that you have invited me to meet with you on the twentieth anniversary of the West Coast evacuation of 1942. This evacuation interrupted jobs as well as business and professional careers and seriously disturbed the lives of all of the West Coast folks of Japanese ancestry. Some of you were called up to move several times during the period of 1942 to 1945 with all of the confusion, disruptions and emotional upheavals attendant upon such moves. Some of you here among the younger Nisei or Sansei probably remember little of the prewar struggles and some may even have little memory of the evacuation and center life. For that reason a bit of history may be in order. And it may also help in another way since history often provides perspective which is not always evident at the immediate times when history is in the making.

Records show that there were only eighty people of Japanese ancestry reported in California in 1884. In 1900 there were some 24,000 Japanese in all of the continental United States. At the time of the "Gentlemen's Agreement" in 1908 between the Governments of Japan and the United States to restrict further immigration, there were about 50,000 foreign born Japanese on the mainland of the United States. In 1920, of the total of 111,000 folks of Japanese ancestry here, some 81,000 were foreign born. So it is clear that the major influx of Japanese immigrants took place between the 1880's and the 1920's and was especially heavy during the first decade of the present century.

The anti-oriental campaigns which got under way as early as 1870 were pointed at the Chinese population which had preceded the coming of the Japanese. These campaigns of the 1870's led to the adoption of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which was re-enacted at regular intervals until the Oriental Exclusion Act of 1924 became effective. There was evidently some let-up in these scurrilous and vicious campaigns after 1882 until around the turn of the century when they picked up again and this time the perpetrators used the Japanese population as their main target. During the early years of these campaigns they were backed mainly by the trade unions and the professional politicians associated with them.

Then during the first few years of this century, the Joint Immigration Committee, under the leadership of V. S. McClatchey, came into existence in California. It brought together the State Federation of Labor, the State Grange, the Native Sons of the Golden West, the State Attorney General and later the American Legion. This federation of economic and political interest groups became one of the most potent of the organizations that were involved in the anti-oriental campaigns for nearly forty years. There were others such as the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League which was organized in 1905.

During the first twenty five years of this century, as you know, there were many discriminatory acts, legislative and otherwise. Two of the worst legislative actions were the Alien Land Law passed first in California in 1913 and the Oriental Exclusion Act enacted by the U. S. Congress in 1924. In the West Coast States there were also anti-miscegenation laws, discriminatory licensing acts and many other similar enactments. Along with this, we had the ever increasing tempo of the "Yellow Peril" campaign carried on by certain West Coast newspapers and reaching out across the country.

Through all of this discriminatory activity the Issei were quietly and effectively carrying on their work on the railroads and in the beet fields or getting themselves established in business, farming, gardening, or the professions.

Between

1910 and 1920 many were getting

married to the beautiful young ladies who came over from Japan. Some of

those young ladies are here this evening and they are still beautiful.

The Nisei, as they came along, attended the public schools. Some also

attended Japanese language schools and some were sent to Japan for

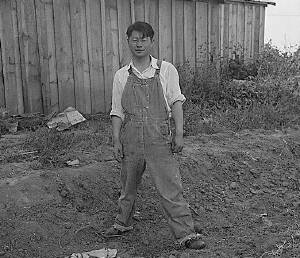

study. [PHOTO: "Member of a farm

family of Japanese ancestry the day preceding evacuation. He said, 'I

am going to have a vacation -- a long one -- I had no long vacation

since I was born.'" (Woodland, Calif., 05/20/1942)]

Between

1910 and 1920 many were getting

married to the beautiful young ladies who came over from Japan. Some of

those young ladies are here this evening and they are still beautiful.

The Nisei, as they came along, attended the public schools. Some also

attended Japanese language schools and some were sent to Japan for

study. [PHOTO: "Member of a farm

family of Japanese ancestry the day preceding evacuation. He said, 'I

am going to have a vacation -- a long one -- I had no long vacation

since I was born.'" (Woodland, Calif., 05/20/1942)]Here again it is interesting to note that there were according to the records about 5,600 married women here in 1910 and some 22,000 in 1920. The American born Nisei numbered 4,500 in 1910, about 30,000 in 1920 and nearly 80,000 in 1940 the year of the last census before evacuation. At that time out of a total of about 127,000 people of Japanese ancestry, there were slightly more than 47,000 Issei as compared with about 81,000 in 1920. Allowing for deaths, it appears that some 30,000 Issei returned to Japan between 1920 and 1940. Most of them undoubtedly went back during the 1920's because of anti-oriental agitation which led to the Exclusion Act of 1924 and which continued after its adoption at a period when it appeared that there would be no let-up in discrimination and hate campaigns. However, as indicated earlier, more than 47,000 of you who had come from Japan continued to live quietly and to work hard at your various professions up to the time of the evacuation.

My hat is off to all of you who so unobtrusively carried on in spite of all of the discrimination, race-baiting and name calling. It required a brand of courage and devotion to family and business which very few people of any national origin could match.

There were mixed feelings and mixed loyalties, of course, and this is understandable. After all few people have ever had the experience of living in a country where they could not become citizens; few other people have suffered the many discriminatory acts which were brought down upon you by cruel or unthinking individuals largely because you were not eligible for citizenship. This important fact -- the lack of opportunity to attain citizenship -- was overlooked by many people in the United States who were not familiar with the facts and they wondered why you had not been "patriotic enough" to become citizens.

After all of this came the war clouds of 1940 and 1941 culminating in the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. This attack was followed by a few weeks of quiet but fearful shock. Then the tom-toms of the race baiters began to beat out messages of hate, fear, and malicious rumor which led to a state of confusion and a gradually increasing demand for governmental and military action. It was a demand which came partly from those with economic axes to grind and partly from people who were emotional and badly frightened. As a result, in late February and early March of 1942, the crowning blow was struck. The evacuation of all people of Japanese ancestry from areas of the West Coast -- including all of California, Oregon, Washington, and small segments of Arizona -- was ordered by the late Lieutenant General John L. deWitt who was then in command of military activities in the area. Seldom in the history of the civilized world has such a blow fallen upon any people such as this one which came down upon the heads of 110,000 hard-working, peace-loving, well-disciplined people ranging in age from infancy to more than eighty years. Two thirds were American-born citizens and the other one third were individuals born in Japan who had never had the opportunity to become citizens of the land of their adoption. Several hundred of the Issei who were most active in business or in community affairs were interned and nearly all others were gathered into assembly centers and later moved into ten relocation centers. There were, however, about 8,000 people who voluntarily evacuated during a short period of free movement and many of these later voluntarily came to live in the relocation centers mainly because of discrimination or fear.

The evacuation meant disruption of jobs, businesses, or professions and the division of families in many cases. The movement first into assembly centers and from assembly centers to relocation centers involved difficult and drastic adjustments for many thousands of people.

Some evacuees, after a few weeks or months, did adjust to the new conditions and seemed to enjoy camp life for most of three years or more. Some of the elderly ladies who had worked hard in the home and on the land apparently enjoyed the first real opportunity for rest that they had had for years as they took courses in flower arrangement, attended English classes or indulged in other leisure-time activities.

I remember quite vividly an incident during one of my visits to returned families in the Central Valley of California in the fall of 1945 which illustrated the reaction of some upon leaving the centers. We stopped at a ranch home where the packing boxes labeled Poston, Arizona, were still in the backyard. The whole family was in the orchard picking plums. We located the head of the family and he called everyone together to introduce us. When the mother of the household came forward with her bucket in hand to greet us, I said, "Are you glad to be home?" Her immediate reply was "No". I asked why not and she quickly said, "Too much work". Everyone laughed but to her it was a very serious matter.

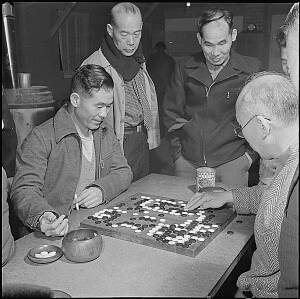

Another group who apparently enjoyed camp life after the weeks of adjustment were many of the elderly bachelors. They were men who had been, in the main, itinerant farm laborers for most of their lives and I suspect

their bones were beginning to ache. They found peace

and enjoyment in the comparatively light work, the endless games of

"Go" and the companionship of center life. On my last visit to the

Minidoka Center, I was asked if I would arrange to have breakfast with

the farm crew who lived in quarters somewhat removed from the main camp

and had their own mess hall. I

agreed to do so and, after a hearty

farmers' breakfast, they said that they liked it there and they

were going to stay. They were very serious about it. I had to tell

them, of course, that on a certain date the mess hall and all related

services would be discontinued and that they would not be happy with no

services and nothing to do. We spent an hour and one-half discussing

the matter and I am sure that I never did convince them because, as you

may remember some of them required real persuasion to board the

trains that eventually took them home. [PHOTO: "A group of

centerites gather around two of the center's expert Go players. The

game, popularly conceived as a game of military strategy, is more

nearly a battle of keen wits, though even this has been frustrated by a

six-year old boy who recently defeated 13 players in simultaneous games

at this center." (Heart Mountain, 01/04/1943)]

their bones were beginning to ache. They found peace

and enjoyment in the comparatively light work, the endless games of

"Go" and the companionship of center life. On my last visit to the

Minidoka Center, I was asked if I would arrange to have breakfast with

the farm crew who lived in quarters somewhat removed from the main camp

and had their own mess hall. I

agreed to do so and, after a hearty

farmers' breakfast, they said that they liked it there and they

were going to stay. They were very serious about it. I had to tell

them, of course, that on a certain date the mess hall and all related

services would be discontinued and that they would not be happy with no

services and nothing to do. We spent an hour and one-half discussing

the matter and I am sure that I never did convince them because, as you

may remember some of them required real persuasion to board the

trains that eventually took them home. [PHOTO: "A group of

centerites gather around two of the center's expert Go players. The

game, popularly conceived as a game of military strategy, is more

nearly a battle of keen wits, though even this has been frustrated by a

six-year old boy who recently defeated 13 players in simultaneous games

at this center." (Heart Mountain, 01/04/1943)]There was another side to the coin, of course. Many people in the centers had serious worries because of the divided families or interrupted business or professions; many were worried about their property and a host of other matters.

There are many things that could be said about this period of three or more years, but I must limit my comments to some of the most important and most crucial items which in one way or another affected the lives of all people within the centers.

First there was the general strike at Poston, Arizona in the fall of 1942 where the acting project director had the good sense to handle the matter calmly and without the intervention of the military. This was followed closely by the Manzanar incident, in eastern California, which unfortunately involved some loss of life which I shall always regret. This was one of the blackest chapters of the relocation center experience.

As you know, this was a period of real tensions. As Director I had been on the job less than half a year and I will admit to you now that I lay awake nights and came as close to losing my mind in early December of 1942 as it was possible to do and still remain sane. Because of the Poston and Manzanar disturbances, we were being pressed to do many drastic and foolish things such as establishing a large police force in each center. Under these pressures, what we did was to call a meeting of all project directors and key staff members and at that meeting we agreed to carry forward on the road that had been previously mapped out until we could determine where changes should be made after a calm review in order to avoid any action that may have resulted from panic. It was our first bad public relations problem but others were to follow both inside and outside of the centers.

Next was the very important decision to initiate plans for the 442nd Combat team and the attendant registration in all of the centers. This led to real emotional upsets in some of the centers, especially Tule Lake and Manzanar, where many refused to register. The emotional upsets, of course, were understandable for they resulted in part from mistakes which I and members of my staff and the military were inclined to make because it was most difficult for us to view matters from where we sat in the same way that people in relocation centers, with their experiences of evacuation and special hardship, viewed them. Consequently, in the hurly burly of wartime speed and tensions, the demand for fast action sometimes led to mistakes which caused situations that might not have happened in a calmer time and a more normal atmosphere.

In this connection I very well remember a visit to the Tule Lake center only a few weeks after the famous registration of 1943 when some 3,000 had refused to register. We arranged for a mass meeting on one of the evenings during my visit. The meeting started at eight in the evening and lasted until after midnight. Father Dai Kitagawa, a young Episcopalian Minister, served as interpreter and the whole meeting was conducted in the Japanese language with my replies to questions and comments interpreted. It was a very serious meeting; tensions were high; the residents really wanted to know the answers. There were deep worries and many misunderstandings. The atmosphere remained tense, serious and perhaps a bit unfriendly until about 11 o'clock when one of the bachelor Issei asked a question which brought down the house and which I, of course, did not understand. According to the interpreter, what he said that one of the things he did not like about the center life was that he could not get anything to drink such as whisky, beer, and wine and why didn't we arrange it so he could get some. After I answered his question in good humor and we all had another laugh, the tensions subsided and we had a most friendly meeting for another hour or more. As I remember it, the group thereafter would not allow any more tough or unfriendly questions and they made it clear, as groups have a way of doing, that the questioning would have to be constructive. This illustrates, I believe, the problem we had in communication and arriving at understanding because of the widely different points of view as well as the difference in language and in cultural background.

There were, of course, many other important developments during the years of exclusion. The action of the U. S. Army in recruiting and training young men from the relocation centers in language schools for service in the Pacific was well handled and their service was of great importance both at home and in the combat areas.

In 1943 the advent of the segregation program and the establishment of the Tule Lake Center as the segregation area was another period of confusion and high tensions. This movement brought together a heterogeneous group of 20,000 people. Some of them were quiet, peace-loving folks who decided to return to Japan because they felt that they did not want to face an uncertain future in the U. S.; then there were several thousand original residents of Tule Lake who just decided to stay on there even though they were eligible to move to another center; and intermingled with these two categories in the same center were some ambitious and power-hungry individuals along with a few tough boys such as the "Sand Island" group who were sent over from Hawaii by the military because they did not know what else to do with them. In the midst of all of the confusion and emotions resulting from this move and from the strange mixture of people it had brought together, an accident provided the opportunity for the "power boys" to arrange a strike of farm workers. This was followed closely by my visit there on November, 1943 and at that time the leaders then in power arranged for a meeting of all center residents who were herded together, following a noon day mess hall announcement, while long talks were held in the project director's office. Shortly after I left the center a battle developed between the police and a group of tough boys who were trying to stop the movement of trucks out to the farm. As a result, the military were called in to take over and they immediately cut the center off from all news gathering media. Meanwhile many frightened employees and tradesmen had left the center telling wild stories and starting dozens of rumors which were picked up by reporters and published in newspapers all over the country. Because each of these allegations had to be carefully checked and because of the military ban on news from the center, it was about two weeks before the facts could be sorted out and presented to the public. In the meantime some of our best friends turned against us and the press really came down hard upon our heads. It was the worst public relations problem that we had to deal with throughout the four years of WRA. Thank God for the 100th Battalion and the 442nd Combat Team which went into action on the battlefields of Italy soon after the Tule Lake affair and with their heroic exploits helped greatly to offset the damage that had been done. Their wonderful combat record which was widely publicized with the active help of the War Department, continued to be our best weapon against the haters through the very last phases of the WRA operation.

The relocation program, which helped establish 40,000 people from the centers all across the country in States east of California, Oregon, and Washington by 1945 before the centers were closed, in itself was of great importance in securing the support and understanding of people in communities that never before had seen a person of Japanese ancestry. Then came the final resettlement with the closing of the centers in 1945 which, of course, meant another move for thousands of people with all of the disruptions, heartaches and readjustments that accompany such moves.

What has come of all of this turmoil and discrimination and these emotional tensions which you and some of us experienced? What does more recent history show? What were the gains and the losses and what have we learned as a result of it all?

First of all, out of all of the confusion, prejudice and misinformation or lack of information, a number of important truths have emerged. Thanks to the Issei, it is now widely recognized that the Japanese-American communities both in and out of relocation centers were and are among the best disciplined groups of people anywhere. The records show that they have been law-abiding to a much better degree than the average run of communities. The self-central and good behavior of the relocatees, the excellent services they rendered to employers, the excellent work habits instilled in the Nisei children by the Issei fathers and mothers; all of these factors not only made our relocation job much easier but gradually created a climate of public acceptance for people of Japanese ancestry generally across the country. The habits of cleanliness which appear to be so universal among Japanese people have been most impressive and most helpful. The insistence on the part of the Issei that the Nisei take full advantage of the educational opportunities available to them has been a great contribution not only to the Nisei but to the American community in general. All of these wonderful basic qualities plus the understanding and support of the Issei in the recruitment for the 442nd Combat Team and the recruitment and training of the boys in the Army language schools who later rendered such outstanding service in the Pacific combat area; these things coupled with the magnificent record of the 442nd Combat Team made it possible to lick the campaigns of the racists, including the American Legion or at the very least to spike their guns. The "Yellow Peril" propaganda is no longer heard in our land and I fervently hope that it has been laid to rest for all time. Discrimination embodied in laws has been largely eliminated by revision of the immigration statutes and by action of the courts or the state legislative bodies. Thanks to the Japanese American Citizens League and the U. S. conscience at least partial remuneration has been made for evacuation losses. The Nisei and Sansei have been largely freed from the kind of discrimination that they have suffered in the past.

We have seen in all of this a demonstration of a real democracy in action. Step by step as the good people of the United States learned of the wrongs that had been committed and the myths that had been foisted upon the American public, they were stirred into action. As a result many wrongs have been righted and amends have been made wherever it has been possible. The good people in our democracy sometimes move more slowly than the people of ill will but when they become convinced that the bill of rights and all of our guidelines for democratic action have been set aside, they do move to rectify the situation and they keep at it until the job is done.

As the beneficiaries of this ability of democracy to right its wrongs, I hope that you will try to explain the power of public opinion that has resulted in your current unprecedented acceptance in this country to those in Japan, in Asia, and elsewhere, where newly independent peoples are looking to us for leadership. It is hoped that they can be persuaded that our system of government is best for them. This is an obligation which I believe that you owe, as citizens, to the United States and I am hopeful that your response will be as unanimous and heartwarming as was your response to the demands and challenges of evacuation and its aftermath.

Now I would like to pay tribute to a few people or groups who have been your friends and mine through thick and thin, when the fight was at its hottest. I wish particularly to mention Clarence Pickett and the American Friends Service Committee, which includes such wonderful people as the late Anne Cloe Watson of San Francisco; the Federal Council of Churches, now known as the National Council of Churches; the Church of the Brethren; George Outland, former Congressman from California; Chet Holifield, Congressman from Los Angeles; John Coffee, former Congressman from Washington State; John McCloy, Assistant Secretary of War during WRA days and more recently one of the Nations outstanding public servants both at home and abroad; Monroe Deutsch of the University of California; the late General Joseph Stillwell of the U. S. Army; the late Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior; Edward Ennis, formerly of the Department of Justice; John Thomas of the Baptist Group; Ruth and Harry Kingman, of Berkeley, California; and the magnificent Galen Fisher who is no longer with us. There were many other individuals and groups who should be mentioned but time does not permit. In addition I want especially to pay tribute to the Japanese American Citizens League which at times during the war was unpopular with certain Japanese American groups who were disillusioned by the evacuation and the widespread discrimination. The leaders of the JACL have had the courage, the vision and the know-how to render great service in the winning of many battles for the Nisei and Issei against discrimination and for positive action and good causes of many kinds both during the war and over the past 17 years. I know of no organization of such small size that is as influential or as well respected in the Congress of the United States as the JACL has been. Thanks in large part to Mike Masaoka and his wonderful wife Etsu, and to Saburo Kido, Larry Tajiri, Hito Okada, George Inagaki, Tom Yatabe, the late Jimmie LaCaneola[sp? handwritten in], and more recently Mas Satow, all of whom along with many others have worked hard and long; the organization has been held together through bad times as well as good and the overall record of accomplishment has been brilliantly impressive.

Mike Masaoka (second from left), national secretary and field executive of Japanese American Citizens League, and a group of friends chat before evacuation. (San Francisco, 4/25/42)

-- Table of

Contents --