U.S. War Department

File No. 48-32

WAR CRIMES OFFICE

Judge Advocate General's Office

SECRET

(Copy # of 74)

23 April 1945

S/sh23 April 1945

A-202

SECRET

By authority of A. C. of S., G-2

Date 23 4/ '45 Initials (S.B.)

By authority of A. C. of S., G-2

Date 23 4/ '45 Initials (S.B.)

REPORT FROM CAPTURED PERSONNEL AND

MATERIAL BRANCH

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE DIVISION, U.S. WAR DEPARTMENT

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE DIVISION, U.S. WAR DEPARTMENT

Because there has been considerable discussion of the issue of loyalty of persons of so-called "dual citizenship" in the present war, this report of interrogation of an American-born Japanese P/W, who volunteered to serve as a radio monitor in Japan, is being reproduced. P/W was captured 9 July 1944 on Saipan and interrogated in the U.S.A. 31 March 1945. Information given is considered truthful on civil matters but unreliable as regards military.

- CHRONOLOGY AND EXPERIENCE OF P/W.

- NISEI FROM AMERICA IN JAPAN.

- NISEI AS RADIO MONITORS.

- CONTACT WITH OUTSIDE WORLD THRU SHORT-WAVE RADIO.

- ATTITUDE OF NISEI TOWARD THE WAR SITUATION.

- NISEI IN JAPAN AS A NUCLEUS FOR A JAPANESE UNDERGROUND.

- MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS OF INFORMATION.

Opinion of U.S. Broadcasts. Evaluation of Japanese Medical Services. Temporary Workers. Uniforms Worn by Radio Monitors. Pay of Radio Monitors. Pay of Regular Army Men in Overseas Service.

I. CHRONOLOGY AND EXPERIENCE OF P/W.

P/W 1458 was born in Waimalu, Oahu, Hawaii, on 9 March 1921. He graduated from Farrington High School, Honolulu, in June 1939, and in August went to Japan; completed one year at Meiji University but lost interest in his subject -- commerce -- and dropped out in 1943. (Probably because of Japanese language difficulties). P/W's brother and sister are still living in Hawaii.

Training at Meiji University:

While P/W was a student at Meiji, he took the regular military training, which was given to all students once a week. At first it took only two hours, but after the spring of 1942 it was stepped up to three. It consisted chiefly of close order and bayonet drills. On only one occasion did P/W fire live ammunition; his group went over to Narashino, Chiba Prefecture, for this practice. P/W fired 3 rounds. On rainy days, trainees would hear lectures on tactical problems, which P/W did not understand.

Once a year, the trainees went out for Yagai Kyoren (field training). They spent about three days on bivouac, and in mock battle exercises. No live ammunition was used, but blanks were issued for the maneuver.

Uniform for military training was a special plain brown uniform, with no insignia or chevrons of any kind.

Mizuho Gakuen Experience:

Upon arrival in Japan, P/W entered the Mizuho Gakuen, a special dormitory-school in the city of Kawasaki for Nisei, both male and female, desiring to learn Japanese. This school is at Masugata Yama in Inada Noborito; and is under the supervision of the Takumu Sho (Ministry for Overseas Affairs). At first the course consists mainly of Japanese language study, but, as the students become more proficient, they begin to study Japanese history and geography. At the height of its enrollment, the school had about eighty students; at present, (P/W believes) it is down to thirty.

Evasion of Regular Army Service:

Although P/W had turned 20 in 1941, his Army physical examination was deferred because he was a student at Meiji. After leaving the University, he was due to come up for examination, consequently the resident tutor at Mizuho Gakuen advised him and three other Nisei to volunteer for radio monitoring service. Preferring anything to the Army, the four Nisei followed this advice which, according to P/W, had more official Army pressure behind it than was at first apparent. Starting in January 1944, the four went to the War Ministry monitoring room once or twice a week as observers. P/W stated that his parents approved of this method of evading regular Army service.

| 1944 | -- |

Jan | -- |

Volunteered for radio monitoring. |

| 10 Mar | -- | Left Yokohama for Saipan on Hibi Maru. | ||

| 18 Mar | -- | Arrived Saipan. Hospitalized for yellow jaundice contracted aboard ship. | ||

| Late Mar | -- | Began radio monitoring. | ||

| 1 May | -- | Hospitalized for amoebic dysentery in Garapan until US attack. | ||

| Late June | -- | Discharged from hospital, though not yet well. When the US attack began, the hospital and its patients were evacuated to the hills. When it became necessary to make room for the battle wounded, medical patients were discharged even though some, such as P/W, were not yet cured. After wandering in hills, prisoner was captured on 9 July. | ||

II. SOME NISEI FROM AMERICA IN JAPAN.

| ISHIDA, Charles | -- |

Age about 35, from State of Washington. Broadcaster for Radio Tokyo. |

| KUWABARA, Mitsugi | -- | From Alberta, Canada. Radio monitor on Saipan, March-July 1944. |

| NAKANO, Aiko | -- | From Arizona. Worked for "Japan Times." |

| NAKASHIMA, Miss ? | -- | From Canada. Radio monitor in Japanese War Ministry. |

| SATO, Minoru | -- | From B.C., Canada. Radio monitor on Saipan (March-July 1944). |

| SHIMOGAWA, Isamu | -- | From Hawaii. Radio monitor on Saipan, (March-July 1944). |

| SHIRAKAWA, Takeshi | -- | From B.C., Canada. Radio monitor on Saipan (March-July 1944). |

| SUYAMA, Miss ? | -- | Canadian. About 27. Broadcaster for Radio Tokyo. |

| TOKYO ROSE | -- | Identity unknown by a Nisei. |

P/W claimed that few Nisei were involved in this special type of service since most of them had been drafted in the regular way and were now either in the Army or the Navy. He thought many of them were in Manchuria.

III. NISEI AS RADIO MONITORS.

Of the four Nisei who were doing radio monitoring on Saipan, three did the actual listening while one translated. The translator's work was edited by Probational Officer SHIMIZU, in charge of the monitoring section, and handed in to Major YOSHIDA of the 31 Army at 1000 daily.

Since only three men were available for listening and the day was divided into four shifts, one man would stand twelve hours duty every third day. Shifts ran from 0800-1400; 1400-2000; 2000-0200; and 0200-0800. Optimum listening hours were from 1800 to 1800. There was little reception in the morning. At peak hours, the man on duty would be helped by one of his friends who was off duty, and the two would take notes on the same program so that one could catch what the other missed.

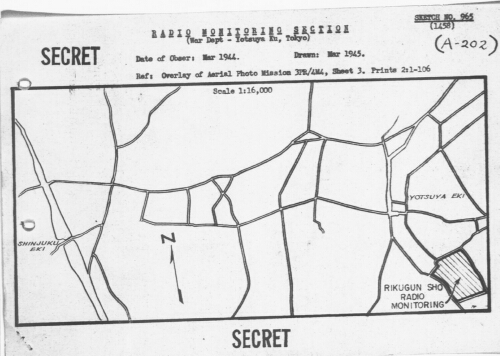

At the War Ministry listening post in Tokyo (See Sketch 965 for its location in Yotsuya), three monitors and two or three translators were on duty at a time. They were supervised by a Captain and a 1st Lt. The day was divided into three eight-hour shifts. Optimum listening hours began around 1600 and lasted practically through the night. During mornings, static was bad.

Recording or transcribing machines were not used on Saipan, nor did P/W see them at the War Ministry. He heard that the Gaimusho (Foreign Affairs Ministry) did all of its monitoring from transcriptions.

Prisoner had little idea of the use to which these listening reports were put. His orders were to take down all "war news." During the interrogation, he listened to an American network news broadcast and took notes as he used to do in his school work. The result was a lot of very fragmentary notes which would have to be transcribed immediately if any sense was to be gained from them. P/W was inaccurate in reading back some of what he had written, and could not remember what many of his own notes referred to. (This could partly be attributed to the fact that P/W was out of practice. However, the inference to be drawn from the results of P/W's listening, which he said was of about the same calibre as the other men with whom he worked, is that if it is desired to make sure that certain special items which we broadcast are clearly understood by the Japs, they should be read by shortwave announcers especially slowly, with adequate pauses to insure that the unskilled monitors will be able to catch everything that was said.) P/W assumed that the monitors' reports were used to gain clues as to present and future US military activities. He concerned himself primarily with general military and naval reports, such as launching of new ships, etc., and with operational reports from the Asiatic-Pacific theatre. The first report in Japan of our landings at Halmahera came from the American broadcast which was picked up at the War Ministry monitoring station. P/W thought that the War Ministry reports were turned in to a member of the General Staff for evaluation; he could give no details on this.

Shortwave sets, mostly of American make, were used for monitoring. At the War Ministry monitoring station in March 1944, P/W noticed only one Japanese radio, several Philco's, and several other American makes -- total five or six. In the field, P/W's section had eight or nine sets, but only three (Philco and Majestic) were found to be operational.

IV. CONTACT WITH OUTSIDE WORLD THRU SHORT-WAVE RADIOS.

As far as P/W knew, no civilian was allowed a shortwave set in Japan, and he himself knew of no other sets than those at the monitoring stations of the War and Navy Ministries, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, all three of which carried on regular monitoring activities. Whether or not the Metropolitan Police had a shortwave radio, P/W did not know. He had never heard of violations of the ban on shortwave sets, and had never heard a shortwave broadcast before going to work for the War Ministry.

When P/W and his three friends went to work for the War Ministry, they were cautioned by a Mr. NAITO (P/W thought his first name ended in "so"; and that he had been Japanese consul in Hawaii), resident tutor at Mizuho, against discussing what he heard over the air with others. He himself complied with this strictly and believes the other three did also. The only way that the American propaganda would be passed around was by some of the other Nisei describing it to their friends, P/W believes this happened sometimes, but not to any great extent.

P/W told of one Middle School student living at the dormitory who came to him one day with the story, told to him by his school teacher, that a certain Japanese possession had been taken by the Allies. This news had not yet been released by the Japanese authorities, but P/W had heard it over shortwave. He said that it was released to the general public within the same week.

When news of a defeat or casualty reports are released in Japan, the specific area is sometimes not mentioned, but merely generally indicated, such as Nampo, (Southern Area). This was especially true of the reports from some of the smaller Pacific islands which fell to the USA.

V. ATTITUDE OF NISEI TOWARD THE WAR SITUATION.

P/W showed himself a curious mixture of American and Japanese cultural patterns. He is definitely not deeply patriotic nor loyal to either, however. At times, he professes a desire to return to Hawaii after the war and take up his American citizenship once more. This feeling is not expressed with much enthusiasm, nor does he demonstrate any great love for American institutions. He gives as the reason for his preferences of America his difficulty with the Japanese language and the fact that "in Hawaii you could play more." On the other hand, he has received virtually no Japanese indoctrination, and what he has heard he has not "swallowed." He is still, he feels, more proficient in English, which is his native language.

His attitude toward his present position is typically Japanese. He "has been caught, and the situation has no visible remedy." He is prepared to suffer whatever consequences there may be, even up to being returned to Japan after the war, if need be, although he has some fears as to the treatment he would receive there.

According to P/W, he considers himself fairly representative of most Nisei in Japan, whose one desire is to have the war over. They feel that they have been caught in a war which is not theirs. At present, being in Japan, they are loyal Japanese. Some, he feels, are more sincere in this than others, but in general, the number of Nisei in Japan at the time of the Pearl Harbor incident who preferred to remain in Japan permanently was small. Most Nisei today, he said, are war-weary, and tired of worrying about being Japanese or Americans. Their citizenship was dual, and the resulting split in their patriotism leaves them with little hate or love for either side.

P/W thought that on the whole, life in Japan was harder for Nisei women than for men. "After all," he said, "isn't America the woman's paradise?" Girls of his acquaintance studied flower arrangement and the tea ceremony; he thought they did not like the tea ceremony, because of the long hours of sitting in an uncomfortable position, but rather enjoyed flower arrangement. P/W felt that their reason for studying these subjects was that these were a part of their cultural sightseeing tour of Japan. P/W seemed to doubt, however, that Nisei girls would ever turn out to be ideal Japanese women.

P/W considered the lack of food and lack of amusements as the chief hardships experienced in Japan. Especially missed was dancing, while English movies seemed next in line. Nisei boys and girls used to go out on dates, but there was little to do so they went to a movie, which turned out to be largely propaganda. In the beginning they had tried dancing in the dormitory but this was soon prohibited.

VI. NISEI IN JAPAN AS A NUCLEUS FOR A JAPANESE UNDERGROUND.

P/W did not know of any underground movement in Japan. Nisei do not constitute an underground, even if they are no more loyal than P/W himself. They are not numerous and are afraid of the consequences of being caught. P/W was questioned on his opinion of the value of our addressing broadcasts to Nisei in Japan; presumably because only Nisei would hear these at their monitoring posts, and it was wondered what reactions such broadcasts would produce.

P/W took issue with the statement that only Nisei were listening. At the War Ministry, for instance, a Captain and a 1st Lt. were in the room, and the Captain, at least, understood English. Some of the listening was done through earphones and some through loudspeakers. Broadcasts which came over the loudspeakers could be heard by the Army officers. P/W thought, however, that at night there were no officers on duty, and that only Nisei were listening.

As to the effect such broadcasts would have, P/W was vague. They would not, he thought, incite the Nisei to any action against the government. They might start them thinking about the possibility of working in the reconstruction of Japan. On the other hand, if an individual reports such broadcasts to the authorities, they might result in closer supervision of the Nisei. P/W did not believe, however, that Nisei would be relieved of their monitoring jobs because of such broadcasts, as, in his opinion, there was no one else who could do the work.

VII. MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS OF INFORMATION.

Opinion of US Broadcasts: Once in a while, P/W picked up a US broadcast in Japanese. His only comment on these was that sometimes the accents were a little funny. Of the regular English news broadcasts which he worked on, and which he thought were not especially beamed at Japan but were aimed at American soldiers overseas, he had few opinions, except that they were not interesting to him personally; he cared only for the broad general military developments and the day-to-day reports with which he had to work bored him. P/W's opinion of a broadcaster depended largely upon how much work was demanded of him in taking down what was being said; thus, Lowell Thomas went too fast for him, and a commentator called Winters, who was also too fast and long-winded, therefore were not popular with him.

Evaluation of Japanese Medical Services: P/W expressed dissatisfaction with the care given him at Garapan Hospital. When he first arrived there, on his second illness in May, he was put in the contagious ward, where patients slept two or three to a room. Here he was seen by a doctor only every three or four days, given a powdered medicine, and fed very lightly. After about twenty days of this, he was moved to a large medical ward, where approximately one hundred patients slept on straw mats in a large room. Conditions were extremely crowded, with mats so closely placed that they touched one another. He saw the doctor only two or three times while at the hospital and continued taking the powdered medicine which had been prescribed. He did not know what this medicine was.

Shokutaku, or Temporary Workers: The difference between a temporary worker (Shokutaku) and the regular Gunzoku, or civilians attached to the military, is that the former have no ratings. Gunzoku are of various ranks, depending on the nature of their appointment. These do not apply to Shokutaku, who have Taigu (literally, "treatment") which would roughly correspond to the comparative rank accorded our Red Cross workers. P/W's Taigu was that of a Hanninkan 2d. Class. The Hanninkan is the lowest of three classes of appointment; a Hanninkan 2d. Class would correspond approximately to the Army's rank of Socho (Sgt. Major). This comparative rank entitled P/W to no privileges. He was required to salute commissioned officers and in fact, his position was distinguished from that of a regular EM only by virtue of his being a non-combatant and of having received no training or indoctrination whatsoever.

Uniforms Worn by Radio Monitors: P/W's uniform consisted of the regular high-collared cotton uniform of the Japanese EM, without insignia of any kind. This was different from the special uniform worn by Gunzoku, which had an open-collared blouse and necktie. He also received at this time one blouse, one shirt, one pair of trousers, and one pair of shoes, as well as socks and underwear. Summer clothing was not issued until arrival at Saipan.

Pay of Radio Monitor: P/W received ¥200 a month, paid all at once. This was far in excess of the pay rate for a Socho, which was the comparative rank he held. He also received free food and board. Other young civilians received only ¥100 to ¥130.

Pay of Regular Army Men in Overseas Service: Insofar as P/W knew, Privates received ¥20-30 per month; NCO's, ¥30-50; 2nd Lts., ¥150; 1st Lts., ¥175. Personnel are paid about the 25th of each month, in cash. P/W said that he was always paid promptly and presumed that this applied to soldiers, too.

For the A. C. of S., G-2,

(signed)

P. E. PEABODY,

Brigadier General, GSC

Chief, Military Intelligence Service

1 SKETCH ATTACHED.

DISTRIBUTION:

MIS 1-12

CPM (files) 13-29

NAVY 30-35

AAF (Air Int) 36-45

ASF 46

JANIS 47

G2 SWPA 48

G2 USAFFE 49

G2 USAFIB 50

G2 USAFC 51

G2 HONOLULU 52

G2 10th ARMY 53

NOUMEA 54

JIOPOA 55-60

CINCPOA (AIC) 61-62

SEAC 63

DC 64-65

STATE DEPT. 66

FBI 67

OSS 68-71

FEA 72

OWI 73,74

-- Table

of Contents --