Forced Labor of Allied POWs in Japanese-Controlled Industries During WWII

Allied prisoners of war (POWs), including Americans, British, Australians, Dutch, and others captured in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, were systematically exploited as forced laborers by the Japanese military and private companies to support the war effort. This violated international conventions, as Japan had not ratified the 1929 Geneva Convention on POWs, leading to widespread abuse. POWs were often already weakened from prior captivity, death marches, hell ship transports, and camp deprivations, making them highly susceptible to injuries and death during labor. Estimates suggest over 35,000 Western Allied POWs died overall, with forced labor contributing significantly through malnutrition, disease, overwork, and brutality. Below is a detailed description of key industries, drawing from camp-specific accounts and broader historical records.

Railroads: The Thai-Burma Railway (Death Railway)

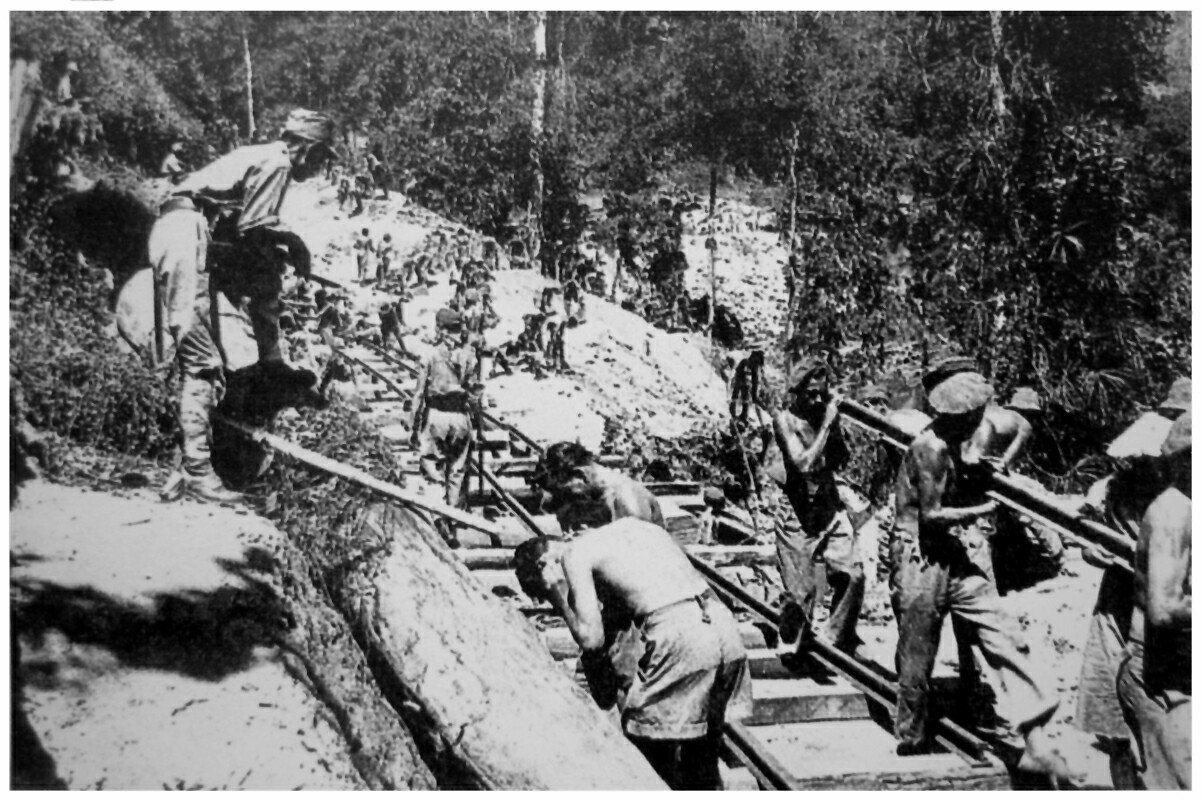

The most notorious example of forced labor on railroads was the Thai-Burma (Thailand-Burma) Railway, a 415 km (258-mile) line constructed from June 1942 to October 1943 to supply Japanese forces in Burma, bypassing Allied-blockaded sea routes. Approximately 61,000 Allied POWs (including 30,000 British, 18,000 Dutch, 13,000 Australians, and 650 Americans) were compelled to build it, alongside 200,000-270,000 Asian civilian laborers (romusha). POWs were rounded up from camps like Changi in Singapore and transported by train or ship to starting points such as Ban Pong in Thailand or Thanbyuzayat in Burma.

Labor involved clearing jungle, excavating cuttings (e.g., the infamous Hellfire Pass, chiseled by hand at night under lights), building embankments, laying tracks, and constructing bridges like the one over the River Kwai. Work shifts lasted 10-18 hours daily, often in monsoon rains, with primitive tools like hammers and chisels. The “speedo” period in 1943 intensified efforts, forcing non-stop labor to meet deadlines. Living arrangements were bamboo huts with earthen floors, overcrowded and infested with insects.

POWs were ill and weak from prior ordeals (e.g., Bataan Death March survivors) and ongoing starvation—rations were meager rice, watery stew, and occasional vegetables, causing beri-beri and weight loss of 20-30 pounds. Medicine was scarce, leading to unchecked tropical diseases. Injuries included cuts from tools, rock falls, and beatings by guards; diseases encompassed malaria, dysentery, cholera (e.g., 600 deaths in Sonkrai camp), tropical ulcers, and diphtheria. High mortality stemmed from exhaustion, infections in open wounds, and abuse—guards crucified or tortured slow workers. About 12,621 Allied POWs died (20% rate): 6,904 British, 2,802 Australians, 2,782 Dutch, 133 Americans. Post-completion, survivors maintained the line or were shipped elsewhere, with atrocities like the Sandakan Death Marches claiming more lives. Other railroads, such as the Sumatra Railway (Pekanbaru Death Railway), saw similar brutality, with 700 Allied POW deaths out of 5,000.

Coal and Mineral Mines

Thousands of POWs were forced into mining across Japan and occupied territories, supporting steel production and munitions. Camps like Fukuoka #17 (Omuta) in Kyushu held over 1,700 POWs (mostly Americans, with British, Australians, Dutch) working in Mitsui-owned coal mines and zinc smelters from 1943-1945. Labor included 12-hour shifts underground, extracting coal in groups of 15-20, with one day off every 10 days. At Sendai #3-B (Hosokura), 281 POWs (mostly Americans) mined lead and zinc for Mitsubishi, enduring deep snow marches and unheated barracks. Tokyo #8-B (Hitachi Motoyama) involved 293 POWs in copper mining 150-160 meters deep, sealing tunnels and hauling ore naked in sweltering, poorly ventilated shafts.

POWs were weakened by malnutrition—rations of 300-700 grams of rice daily, leading to 60-pound average weight loss and oedema. Cold, damp conditions and prior hell ship ordeals exacerbated vulnerability. Injuries were rampant: falling rocks crushed limbs (e.g., hands requiring surgery), cave-ins trapped workers, and assaults with iron bars caused fractures. Diseases included beri-beri, pellagra, dysentery, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and ulcers from vitamin deficiencies. Mortality was high: 15+ deaths out of 501 at Omuta (plus 76/110 in transit hospital); 19/281 at Hosokura; 5/293 at Hitachi, mainly from pneumonia and exhaustion. Atrocities included amputations as punishment. Overall, mining camps had 20-30% death rates due to overwork on weakened bodies.

Shipbuilding and Related Industries

POWs labored in shipyards and docks to repair and build vessels for the Japanese navy and merchant fleet. At Tokyo #2-B (Kawasaki), 312 Americans (later joined by Dutch) worked as stevedores, in steel mills, iron works, and docks for Mitsui Shipping from 1942-1945. Tasks included loading/unloading ships and operating in industrial facilities, often 12-hour shifts. Other sites like Nagasaki and Osaka shipyards used POWs for welding, riveting, and construction, boosting Japan’s naval output.

Overcrowded barracks and sparse rations led to weakness, with many arriving emaciated from hell ships. Injuries from heavy lifting, machinery accidents, and air raids (e.g., 23 killed in a 1945 bombing); diseases like pneumonia thrived in cold, malnourished conditions. Deaths: 18 in the first year at Kawasaki (from 312 to 108 survivors initially), plus raid casualties, due to acute illnesses on weakened frames. High rates reflected the irony of laboring on enemy ships while vulnerable to Allied attacks.

Labor for the Japanese Military

Beyond industries, POWs built military infrastructure like airfields, fortifications, and roads. In the Philippines (e.g., Davao Penal Colony), they farmed for Japanese troops; in Borneo and New Britain, they constructed defenses. Work included digging trenches, loading munitions, and airfield repairs under fire. Conditions mirrored others: starvation diets, no medical care, leading to weakness. Injuries from explosions, collapses, and beatings; diseases like malaria killed many. Deaths: Often 20-40% in such projects, e.g., 2,000+ on Sandakan airfield and marches. The policy of no surrender fostered disdain, amplifying brutality.

Were our POWs ever compensated for their forced labor? If so, when and how much and by whom?

Post-War History of Compensation for Allied POWs of Japan

The post-war compensation for Allied prisoners of war (POWs) held by Japan during World War II, particularly those subjected to forced labor in mines, shipyards, railroads, and factories, has been a protracted and largely unsatisfactory process for survivors and their families. Efforts were shaped by international treaties, national legislation in Allied countries, and advocacy groups like the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor (ADBC), founded in 1946 by former POWs to preserve history, advocate for benefits, and seek justice. Key figures such as Ralph Levenberg (a Bataan Death March survivor and ADBC national commander from 1986-1987) and Edward Jackfert (ADBC commander from 1999-2000) played pivotal roles in lobbying for recognition, declassification of records, and compensation through congressional testimonies and lawsuits. Compensation was rarely direct from Japan to individuals; instead, it came via seized assets, Allied government programs, or limited ex-gratia payments, often decades later and insufficient to address the physical and psychological toll.

Early Post-War Period (1945-1950s): Seized Assets and Initial Claims

Immediately after Japan’s surrender in 1945, Allied POWs received minimal back pay and benefits from their home countries, but no direct reparations from Japan. The U.S. War Claims Commission (WCC), established in 1948, distributed funds from seized Japanese assets (valued at approximately $379 million in 1945, or about $6.5 billion in 2024 USD) to American POWs and civilian internees. Payments ranged from $1 to $2.50 per day of imprisonment for POWs (e.g., about $1,000-$3,000 total for a typical 3.5-year captivity), and civilians received $60 for the first 90 days plus $25 per month thereafter. These were intended to compensate for inadequate food and forced labor, but amounts were modest and did not cover medical needs or lost wages. Similar programs existed in the UK and Australia, funded by seized assets under Allied occupation authorities.

The 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty (effective 1952) formalized Japan’s reparations but waived individual claims against Japan in exchange for peace. Under Article 16, Japan provided lump-sum payments to Allied nations for distribution to POWs and civilians, totaling about $1.012 million (¥364 million) across countries like Burma ($200,000), the Philippines ($550,000), Indonesia ($223,000), and South Vietnam ($38,000), equivalent to billions in 2024 USD. However, these funds were often used for national reconstruction rather than direct POW aid. The treaty’s Article 14 allowed Japan to negotiate bilateral agreements, but no individual POW compensation was mandated, leading to criticism from groups like ADBC for prioritizing economic recovery over justice.

1960s-1990s: National Benefits and Failed Claims

Allied governments provided ongoing support through veterans’ benefits. In the U.S., the Veterans Administration (now VA) offered disability compensation, medical care, and pensions for former POWs, with presumptive service-connected disabilities for conditions like beri-beri heart disease or post-traumatic stress (expanded in the 1980s). Amounts varied by disability rating (e.g., 100% disability could yield $3,000+ monthly in 2024 terms), but these were not reparations from Japan. Australia and the UK offered similar pensions. Attempts to sue Japanese companies for unpaid wages and abuses began in the 1990s, spurred by ADBC leaders like Levenberg and Jackfert, who testified before Congress for declassification of records showing corporate complicity. Lawsuits targeted firms like Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Nippon Steel, seeking $20,000 per POW, but Japanese courts dismissed them citing the 1951 treaty, and U.S. courts followed suit (e.g., In Re World War II Era Japanese Forced Labor Litigation, 2000). The U.S. government often opposed these suits to protect bilateral relations.

2000s-Present: Ex-Gratia Payments and Limited Apologies

In 2000-2001, the UK provided ex-gratia payments of £10,000 (about $15,000, or $27,000 in 2024 USD) to over 16,000 surviving POWs and civilians, funded domestically rather than by Japan. Canada followed with C$24,000 per survivor in 1998. U.S. efforts for additional compensation failed (e.g., 106th Congress bills), but the 2000 Nazi Slave Labor Compensation Act inspired similar pushes, leading to declassification of Japanese records. In 2015, Mitsubishi issued a formal apology to American POWs for forced labor but offered no financial compensation. Other companies like Nippon Steel faced rulings in South Korean courts (e.g., 2018 order to pay 100 million won, about $88,000, to Korean laborers), but these did not extend to Allied POWs. Overall, direct Japanese compensation to Allied POWs has been negligible, with most benefits coming from Allied nations.

Current Campaigns for Compensation by Former POWs and Descendants

As of 2026, with few original POWs surviving (most in their 90s or older), campaigns have shifted to descendants, historians, and memorial societies advocating for recognition, apologies, and compensation. The ADBC Memorial Society (successor to ADBC since 2012) leads efforts, focusing on education, preservation (e.g., Bataan-Corregidor memorials), and pressuring Japanese companies and government for redress. Campaigns emphasize unpaid wages (estimated at ¥278 million, or $3 million unadjusted, for forced labor) and moral accountability.

Lawsuits and Advocacy Against Japanese Companies

Ongoing or recent suits target companies profiting from POW labor:

Territorial examples include Guam’s 2021-2023 law providing $4.13 million to survivors and descendants (up to $15,000 each) for Japanese occupation abuses, funded locally. VA benefits continue for U.S. POW descendants (e.g., survivor pensions), but no new federal reparations.

Japanese Leaders and Politicians Supporting the Cause

Support from Japanese leaders has been limited, often framed as general apologies rather than specific POW aid:

Recent politicians like those in the Liberal Democratic Party have engaged in dialogues with ADBC, but progress stalls on legal grounds. Advocacy relies more on international pressure than Japanese initiative.

japanpow(at)use.startmail.com

Copyright 2001-2026, Wes Injerd. All Rights Reserved.