| Tokyo

POW Camp #8-B Hitachi Motoyama |

Camp List Home About Us

| Hitachi

POW Camp AKA Motoyama Miyata-cho, IBARAKI-ken, HITACHI-shi Timeline: 5 Mar 1944: Established as Tokyo #12-D 11 Apr 1944: 300 Americans arrive, start work on 20th 10 Aug 1944: 150 Americans transferred to Ashio camp, 80 to Mitsushima camp 14 Aug 1944: 230 Americans depart, replaced by 150 Dutch and 80 British Aug 1945: Renamed Tokyo POW Camp #8-B 5 Sep 1945: Rescue effected Satellite map Aerial (July 1946; courtesy of Japan Map Archives) Area map of Tokyo POW Camps The Motoyama camp was located on the southwest side of a valley. A second camp, a smelting plant, apparently was located below this mine. Across the valley was another mine that used Chinese as slaves (see report). There is a memorial there called "Nikko Kinen-kan" (Hitachi Mining Memorial Hall). Lt Col Christensen's description: "Camp located approximately eight to ten kilometers west of the town of Hitachi (on the east coast of Honshu, about 20 miles north of the town of Mito), Ibaraki Prefecture. I believe the small settlement at the site of the camp was known as Motoyama." Photographs: Location Map: Sequence of area maps- Map #1, #2, #3 Dutch funeral (from Short collection) Japanese Staff: Nemoto - Capt, Camp CO Kurita (Gunso) Sgt - Asst CO Mizuno, (Gocho) Corp- Asst CO Civilian (veteran) employees of the Army: Dono - relative rank of Sgt Yuag - relative rank of Sgt Matsuda - relative rank of Pvt Kikuchi - relative rank of Pvt Interpreters: Mr. Kakei Kenji Kuni - formerly an American citizen- "Frank Queenie" Guards: Miyamoto Fujimoto Office Clerks: Tanaka Susuki Hokei Toyahara Medical Attendant: Mr. Nakamura Cook for Japanese: Mr. Ishizaki Information re guards (courtesy of Charles Underwood, son of Maj. Underwood): In respect to the guards of pow

camp Hitachi #8B, Motoyama, formerly Tokyo 12-D:

There were 10 Japanese guards operating in the camp. There were three Japanese Camp Commanders, during this period April 44 to September 45. Charges against these Japanese commanders were brought against seven(1). The Three Japanese camp commanders and their approximate duty dates were: Capt. Ryoichi Nemoto - April to June '44; Lt. Syokoi Matsuo - June '44 to June '45; and Lt. Tjomahi Nakamura from June '45 to Sept. Verdicts as registered by Case number 166 of Yokohama War Crimes Tribunals, 1947-8. Captain Ryoichi Nemoto - Guilty of six of 16 charges sentence to hard labor for 3 years Saburo Kozawa - Guilty of 13 of 23 charges sentenced to hard labor for 23 years First Lieut.Syokoi Matsuo - Guilty of 19 of 37 charges sentenced to hard labor for 17 years Corporal Toshio Mizuno - Guilty of 7 of 9 charges sentenced to hard labor for 17 years Minority Fujimoto - Guilty of 7 of 12 charges sentenced to hard labor for 15 years Masatumo Kikuchi - Guilty of 6 of 7 charges since to hard labor for 12 years Footnote: Lt. Tjomahi Nakamura, for reasons unknown was either not brought to trial, or was not found guilty. (1)Source: extracted from the specification of charge sheets as submitted in1946-7 by Major Charles Underwood, former pow of Hitachi; retyped to affidavits 27 January 1947 by Alvin C Carpenter, chief legal section, Gen. Headquarters Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, signed by Summary Court Officer Capt. John R. Prichard (2)verdicts source: Ginn, John L. "Sugamo Prison, Tokyo: An account of the trial and sentencing of Japanese war criminals in 1948." 1992. |

Primary

Labor Use: Slave labor as miners for the Hitachi Copper Mine [Nippon Mining Company] Hell Ship: Americans arrived on the Taikoku Maru. Affidavit of Lt COL (Inf) Arthur G. Christensen- describes trip in detail

Camp

Rosters at Liberation: Total POWs = 293 (145 Dutch, 80 British; 68 Americans; 5 deaths) List

of deceased: Asst. rosters and info (RG 407 Box 114) Maj. Earl Short diary (courtesy of MacArthur Memorial, Norfolk, VA)

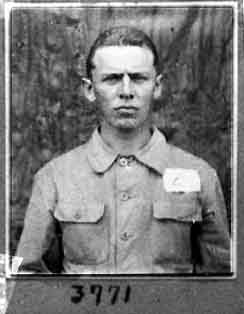

POWS known to be here at rescue: Bahrenburg, James H., Lt Col, O&281569, USA (MC) Christie, Martin, Cpl,272081,USMC Nealsom, William Robert, Maj, O&367089. USA Renka, John I. Jr., 1st Lt, O&416595, USA Robinson, Donald W., Maj, O&380999, USA (MC) Short, Earl R., Maj, O&311554, USA Underwood, Charles C., Maj, O&378597, USA POWS known to have been sent to Zentsuji and rescued at Rokuroshi: Christensen, Arthur George, Lt Col, O&20871, USA (INF) Conrad, Eugene B., Maj, O&394417, USA Evans, Robley D., Capt, O&399426, USA Pictures of American POWs from MacArthur Museum: Can you help identify any of these 59 men? Please contact us. Group 1 (1032kb) Group 2 (998kb) Group 3 (985kb) See this DOC file for known actual POW numbers (courtesy of Opolony) Group 1:

Jose M. Baldonado #25; McCall #40; Combs? #10; Wilkinson #11; Krick

#62; Guiraud? #59; Zull? #58; R.M. Stark #68; Schultz #71 Group photo - Fred Allen Douglass, medic, on the far right, about third row (courtesy of Swager). Hi res image (courtesy of MacArthur Memorial, Norfolk, VA) Camp Photographs & Sketches: Camp flag is at the Truman Presidential Museum & Library. The flag's plaque reads: This flag

was made by Luther Bass, an

American serviceman held captive

in Tokyo Prisoner of war Camp # 8 during World War II. Bass made the

flag from parachutes carrying food and clothing dropped to the camp

from a U.S. B-29 bomber on August 26, 1945.

In 1973, Earl R. Short,

another Camp # 8 survivor, donated the flag to

the Truman Library.Interviews or personal stories: Major Short's report on the nearby Chinese slave camp. Over 200 deaths noted by Chinese. RG 407 Box 114. Donald W. Robinson (photo in Group 2, top left corner): "We made the truck ride to

Cabanatuan, and from then until I went with Art Christensen on a work

detail to Japan in '44, was on medical duty in Group 1, 2, and 3. Saint

wanted me to get off the work detail to Japan, but I had promised

Christensen I would go with him. Fortunately we made it and Saint,

Barber, Gay, Baer all were on the Oryoka Maru and all died." (courtesy

of Karen Robinson, daughter-in-law)

A short history of Motoyama by Martin S. Christie, Capt, USMC |

|

Date of birth:

22 March 1907 Birthplace: ? Former occupation: Senior Ranger with the Forestry Service in the Dutch East-Indies War years: Mobilised as conscripted soldier with the K.N.I.L, forced labour in Japanese copper mines The extract below is from the memoirs of the late Franz Adolf Lörzing, with an afterword by his daughter, Ellen Streurman-Lörzing. (Courtesy of Michiel Busz) "In

the mining camp many of my

comrades died of pneumonia and sheer exhaustion"

After

our surrender, I was taken prisoner by the Japanese along with the

entire army. The last time I saw my wife during the war years, was on

our daughter's birthday, 18 June 1942. My wife gave me some money

through the barbed wire of a new, heavily guarded camp in Garoet and

she was promptly taken by the Japanese guards to their watch house,

while I looked on in powerless fury. Luckily she was soon released

unharmed and I was able to watch her as she walked away from the camp –

and me. Only then did I let go of the barbed wire which my hands had

been clutching until they bled. Only after the war did I hear from my

wife that she and our daughter had spent most of the occupation in the

notorious Ambarawa women's camp in Central Java.

Shortly after June 1942, I was transferred to a prisoner of war camp in Tjimahi. The food there was so bad that I soon got beriberi and pellagra through vitamin deficiency. The retinas in both my eyes were also severely damaged. From Tjimahi I was put on a transport to Japan via Batavia. From 26 to 30 September 1943, I and 3000 other prisoners of war sailed on a small cargo ship, the "Makasar Maru", to Singapore. The four days on board were terrible. Three thousand of us sat in the cargo hold below sea level. We were so closely packed that you could not lie down. There was only one water tap on deck and all three thousand of us lined up to fill our canteens. The hold on the boat was connected to the deck by a narrow, steep, iron ladder and you had to crawl along and over one another to get up top and below. It was so boiling hot in that hold below, that in comparison, the deck in the burning tropical sun was deliciously cool. I sweated so profusely that I did not urinate during the entire four days. My first pee, quite some time after our arrival in Singapore, was the colour of strong tea after a week in the pot. The voyage from Singapore to Japan began on 23 October 1943 on board the cargo ship "Atu Maru". Again we were in the cargo hold below sea level. This voyage was less arduous because there were "only" 1000 prisoners of war. We did run the risk though of being torpedoed by our allies, since they targeted all Japanese ships, not knowing that sometimes allied prisoners of war were on board. On 15 November 1943, our ship arrived in Japan and we stood shivering from cold on the bleak quay of the Japanese harbour, Shimonoseki. The following day we travelled north by train. Our group of 1000 men was split into groups with different destinations. My group consisted of 250 K.N.I.L. prisoners of war. Our train journey ended on 17 November 1943 and we climbed a steep mountain to our mining camp, Ashio. The place was high in the mountains and terribly cold. It remained freezing there – from my arrival in mid-November 1943 to April 1944. Sometimes it was 36 degrees below zero. The barracks were made of thin planks and the heating with wood fires was useless. The food was monotonous and sparse. Partly because of the back-breaking work, my weight dropped to 45 kilos. We had to work hard every day from early morning until evening. Many of our comrades died in this camp, mainly from pneumonia and sheer exhaustion. On 11 August 1944, I and 150 other Dutch K.N.I.L. members left the Ashio camp and travelled on foot, by train, and again on foot to another copper mining camp, called "Motoyama". From that second camp in Japan, I did underground mining work, 150 to 160 metres deep. The ventilation throughout the mine was so bad and it was so hot that you had to work completely naked, with only a Japanese cardboard helmet on and a pair of thin rubber shoes. The work that I did there was always hard with a lot of nightshifts. Amongst other things, it involved sealing old mine tunnels. The filling material consisted of mud and stones. The filling was done in two stages. Applying the lowest layer was just bearable, but applying the highest layer was terrible. The remaining space was so low that you scraped your back when, crawling like a snake, you had to push a flat truck, loaded with wet rubble, to the end of the tunnel where you had to shove the rubble in all the nooks and crannies. Then you had to crawl back with the empty truck. For years after the war, I had claustrophobic nightmares about it. Once, in a rage, I nearly killed a Korean mine worker. (At the time, Korea had been annexed by Japan and the Koreans were a kind of second-class Japanese). This Korean mine worker was a brute who cursed and hit me because he was dissatisfied with my work performance. Once when we were busy depositing pieces of ore in a waste chute, he went too far and my fury gave me Herculean strength. I dragged him to the waste chute as he squealed in fear. I shoved him into the chute with my feet. Luckily he managed to grab the rim of the chute. I hit his fingers with my fists to make him let go so he would fall into the pit. Then I awoke from a seeming daze and realized that I was murdering someone and that the Japanese guards would kill me for it. So I grabbed his wrists and pulled him out of the hole. The Korean threw himself face down onto the ground and lay there for some time. Then he came round and began to speak. From his gestures and Japanese, which I comprehended a bit, I understood that he had taken me for a malingerer who pretended to be weak, but who in reality was so strong, that he (me in other words) could overpower a sturdy Korean. Then he grabbed an iron bar, which was used to loosen debris stuck in the chute, and hit me with it. It was so low and narrow in the tunnel though, that he was unable to use much force. I allowed him three blows, grabbed the bar off him and said that that was enough and that we had to get back to work. I worked like a dog to get him in a good mood, because I was afraid that he would report me to the Japanese military guards. But it turned out that he did not want to let anyone know that he had been bested by a pathetic prisoner of war. After that, I no longer got any trouble from him. A couple of times I was in danger of losing my life. One day, fairly late in the afternoon, I was walking with three comrades through an old mine tunnel. Suddenly the entire width of the tunnel collapsed in front of us. We ran back, but at the same moment a wall of grit and pieces of rock fell down and we were trapped inside a small space. Luckily for us, there was a waste chute connected to that part of the tunnel. We pulled the cover open and we were in luck for the second time: there was only a cubic metre of mud and rubble in the waste chute. We quickly removed this and crawled up the empty wooden chute. With a superhuman effort, we managed to crawl to a tunnel higher up. There then followed a labourious hike. Our mine lamps had gone out and the matches to relight them had got wet. In the pitch dark we had to grope our way along the walls towards shaft openings where successive wooden ladders led us to a higher tunnel. After labouring for hours we finally reached the exit. In normal times we would have been greeted as heroes, but we were met with slaps from the Japanese guards because we were late. Our comrades also blamed us because they had had to spend all that time in the cold standing in line waiting for us. On 20 July 1945 we were startled by heavy bombardment by American warships. As a result, our mine's industrial centre was so heavily damaged that there was not much point working. After the surrender, it took a long time for the Americans to discover our isolated camp. On 8 September 1945, I arrived in Yokohama. I then flew on via Okinawa to Manila where I arrived on 14 September 1945. I lived at the American army camp in Manila until 16 October 1945. I was in a state of euphoria until that day, then I suddenly woke up. I was overcome by an enormous fear about the fate of my loved ones. Shortly afterwards we were told that lists with the names of the dead and survivors were posted in a hangar. I walked to that hangar three times before daring to go in. My wife and daughter Ellen were alive. Of the prisoners of war, my brother Wim had been forced to work on the Burma railway and was still alive. But my brother-in-law, Jo Scholten, my sister Malie's husband, had died in June 1943. Later I received word that my mother, my sister Malie and her three children had survived the Tjideng camp, but that my father had died just before the end of the war in a camp in Semarang. It was not until 15 February 1946 that I saw my wife and daughter again. "As his daughter Ellen, I would like to add something to this abbreviated version of my father's memoirs. I remember his sombre moods in later life. He was depressed by his war experiences. At first he did not want to talk about it much. These memoirs were a relief to him. He had no income during the war years. My parents lost everything. After the war, they had to borrow money and then pay it back. Years of lodgings, a long time without a permanent job at first, no longer being in his beloved Indies. And he also had very bad eyes from his time as a prisoner of war. As his daughter, this saddened me enormously." -- Ellen C.

Streurman-Lörzing

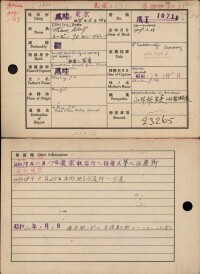

POW

Index Card for Lörzing POW

Index Card for Lörzing |

|