Update on Litigation and Legislation (2001)

by Edward Jackfert

During the month of July, Congressmen Rohrabacher and Honda

offered an amendment to the appropriations bill (HR 2500) for the Justice

and State departments which prohibits both agencies from using any 2002 funding

against U.S. World War II POWs in court. The amendment was overwhelmingly

adopted by a vote of 395-33. Congressman Honda's message to the press was

as follows: "This House has sent a powerful message to the Bush administration

and the State Department that our POWs, who survived unimaginable horrors

during World War II, should not be forced to survive a judicial system that

is slanted against them to achieve the justice they deserve.

It is shocking that the U.S. government continues to oppose to our veterans'

claims against these Japanese companies, rather than helping them resolve

this matter. We should not allow our own government to use the resources

we appropriate to oppose our former POWs in court." Congressman Rohrabacher

remarked as follows: "The U.S. Congress sent the State Department and these

Japanese multinationals who enslaved our American heroes a message, our veterans

deserve their day in court."

The following Congressmen voted against this amendment: Blumenauer (OR),

Blunt (MO), Callahan (ALA), Cannon (UT), Castle (DEL), Combest (TX), Cox

(CA), Cubin (WY), Dicks (WA), Dreier (CA), Flake (AZ), Gilchrest (MD), Granger

(TX), Hansen (VT), Hastings (FL), Hilliard (ALA), Houghton (NY), Hyde (IL),

Kolbe (AZ), Largent (OK), Meeks (NY), Nethercutt (WA), Payne (NJ), Petri

(WI), Schaffer (CO), Sensenbrenner (WI), Smith (MI), Smith (WA), Souder (IND),

Stump (AZ), Watts (OK), and Young (FL). Those of you who reside in any of

these states, take notice, and contact these Congressmen and request their

assistance in matters relating to prisoner of war legislation.

On July 31, 2001, Senator Orrin G. Hatch introduced S. 1272, titled

"POW Assistance Act of 2001" which is worded to assist United States veterans

who were treated as slave laborers while held as prisoners of war by Japan

during World War II, and for other purposes. This bill was cosponsored by

Senator Dianne Feinstein of California.

In a news release Senator Feinstein related the following: "The POW Assistance

Act of 2001 makes clear that any claims brought in state court, and subsequently

removed to federal court, will still have the benefit of the extended statute

of limitations enacted by the state legislatures. The statute of limitations

should not be permitted to cut off these claims before they can be heard

on their merits. Today's bill does nothing more than ensure that these POWs

receive their fair day in Court." Senator Feinstein further remarked that,

"We in the Senate have a moral obligation to do what we can to ensure that

they are justly compensated. I urge our colleagues on both sides of the aisle

to act quickly in support of this bipartisan bill."

On August 2, Senator Jess Bingaman (NM) along with Senator Orrin Hatch (UT)

introduced S. 1302 "Pacific Veteran's Compensation Act." The purpose of this

piece of legislation is to grant a $20,000 gratuity to those veterans that

were prisoners of war of the Japanese military and were utilized as slave

labor in Japanese industrial plants during World War II. The legislation

states that the Secretary of Veterans Affairs may pay a gratuity to a covered

veteran or civilian internee, or to the surviving spouse of a covered veteran

or civilian internee, in the amount of $20,000.

The bill identifies those covered by the bill as member of the U.S. Armed

forces, civilian employee of the United States, or an employee of a contractor

of the United States during World War II; they must have served in or with

United States combat forces during WWII and were captured and held as a prisoner

of war by Japan, and finally were required by the Imperial Government of

Japan, or one of the Japanese corporations, to perform slave labor during

WWII.

Congressman Robert Stump (AZ) seemed to have some reservations relative to

this piece of legislation. Our membership, survivors, and friends residing

in Arizona and all other areas to telephone, fax, or make personal contact

with their elected official in the House of Representatives and request that

he or she support this important piece of legislation.

We would like to point out that there is continual opposition from Japanese

lobbyists throughout the United States expressing opposition to our efforts

currently being conducted in the legislative field. This is being done through

personal contacts of our elected officials in Washington and also in state

legislatures. The Japanese Consul in New York successfully interceded with

the legislatures in Rhode Island and West Virginia and kept a resolution

somewhat similar to that passed in California from being affirmed.

In each instance there was a strong inference of economic retaliation against

the people in each of these states. In West Virginia the Consul wrote to

the Speaker of the House of Delegates as follows: "As you may already be

aware, during this past decade, Japan and Japan based firms have emerged

as one of the largest foreign investors in your state as well as the second

largest market for West Virginia exports, therefore, I would appreciate it

if you would kindly consider our position on this issue." Thereafter, the

resolution was bottled up in the House Rules Committee.

Let's keep the pressure on our elected officials. We have had wonderful media

coverage in the newspapers and on television. The latest coverage was on

August 8, 2001 on ABC's Nightline program. There was an excellent

coverage of what we currently are attempting to accomplish for the entire

one half-hour program. The program was diverse m coverage and exceptional

in its production from the point of view of the former prisoner of war of

the Japanese military during World War II. For further information on our

litigation and legislation efforts please open up the following web sites:

http://www. justiceforveterans.org and http://pages.prodigy.net/edjackfert.

AN OPEN LETTER

TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES

Outrageous ... Reprehensible Irresponsible!! These are but a few words that

express the feelings of the survivors of the Death March on Bataan, Hell

Ships, Prison Camps, and the slave labor detachments of the Japanese during

World War II.

The Americans who were captured in the Philippine Islands and other areas

of the Pacific by the Japanese during World War II were starved, beaten,

tortured, and forced to become SLAVE laborers of Japan's industrial giants

throughout the entire period of the war.

The United States government refuses to permit these former prisoners of

war to sue either the government of Japan or its industrial complexes for

reparations. It is contended that the Peace Treaty with Japan denies the

right to sue to all military and civilian persons who were held captive by

Japan.

However, the governments of Canada, Great Britain and New

Zealand, all signators of the very same Peace Treaty have paid their

service personnel, and in some instances, their civilian citizens, who were

prisoners of war of Japan, reparations in the amounts of $28,000, $25,000

and $30,000 respectively in recognition of the horrendous treatment they

suffered at the hands of the Japanese military and Japanese industries for

whom they were forced to perform slave labor.

An added insult is the attached copy of the item appearing in the June 25,

1987 edition of The Arizona Republic.

Is there any reasonable explanation for the outlandish actions described

in that news item?

We, who suffered the most atrocious treatment known to mankind, ask ... where

is the justice???

Ralph Levenberg Major, USAF (Retired)

POW-Japan 3½ Years

U.S. PAID 141 JAPANESE $28 MILLION SEVERANCE

Arizona Republic

6/25/87

(Knight-Ridder)

WASHINGTON -- In an incident that one congressman called "truly fit for Ripley's

Believe It or Not," the Pentagon has paid more than $28 million in severance

pay to 141 Japanese workers, an average of almost $200,000 each, because

their banking work for U.S. military personnel in Japan was terminated.

John Barber, a civilian employee in the Pentagon comptroller's office, told

a House Armed Services subcommittee that the severance payments were in accord

with the Japanese cultural tradition that workers there are guaranteed lifetime

employment.

Lee Middleton, an assistant vice president of American Express Bank Ltd.

in New York, one of two U.S. banks that employed the workers, said that the

payments were "in keeping with market practices in Japan."

But Rep. John Kasich, R-Ohio, took a different view, terming the payments

"insane" and excessive, and saying he soon will introduce legislation to

ban such a practice.

The payments went to the Japanese employees after Chase Manhattan Bank and

American Express Bank Ltd. lost a contract they had with the Pentagon to

supply banking services to American military personnel in Japan, the subcommittee

was told.

War not over for ex-POWs suing Japan firms

By Mark Austin

Daily Yomiuri Staff Writer

September 1, 2001

On Feb. 23, 1942, American and Filipino troops hunkered at the tip of the

Bataan Peninsula, which had been overrun by the Imperial Japanese Army, listened

to U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt tell them in a radio message that "in

every war there are those who must be sacrificed for the benefit of the whole

war effort."

One of those soldiers was 23-year-old Staff Sgt. Lester

Tenney of the Illinois National Guard's

192nd Tank Battalion.

Fifty-eight years later, Tenney told a U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee hearing

on prisoner-of-war victims of the Bataan Death March that "we suddenly realized

(Roosevelt) was talking about us. We were being sacrificed, abandoned for

the benefit of the whole war effort. Well, senators, we were able to live

with that; after all, we were proud young men and women serving our country,

and we took an oath to protect our country at all costs."

After being taken prisoner on April 9, 1942, and surviving the 88-kilometer

Bataan Death March that claimed the lives of at least 10,000 American and

Filipino soldiers, Tenney was transported to Fukuoka in a "hell ship" and

interned at a work camp. For the next three years, he was turned over to

Mitsui Miike Coal Mine Co. each day and forced to work 12-hour shifts shoveling

coal in the Omuta mines.

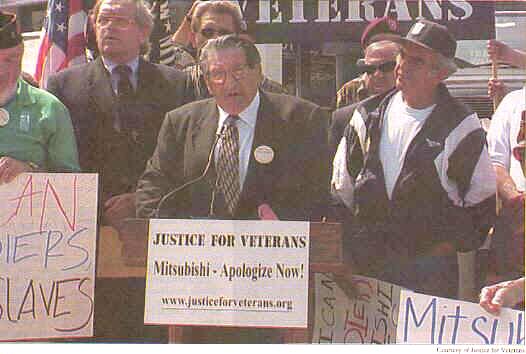

Tenney addresses a rally of former U.S. prisoners of war and their supporters

outside the Mitsubishi dealership in San Diego, Calif., Tuesday. The former

POWs were protesting Mitsubishi's use of slave laborers during World War

II.

Tenney was given little food -- his weight dropped from 84 kilograms to 45

kilograms -- and he still suffers from the beatings he received at the hands

of Mitsui employees. "I have very limited motion in my left arm -- they broke

my left scapula with a pickax -- I wear false teeth because my teeth were

all knocked out, I wear a hearing aid because the beatings to my head ruined

my hearing, my nose is still broken -- still looks like it's all over my

face. I limp every so often, when the pain starts to be very severe in my

hips. I still have nightmares. They're bad enough that my wife gets very

concerned when I start screaming," he told The Daily Yomiuri.

Peace at any cost?

The hearing at which Tenney gave evidence was part of Congressional deliberations

on a bill submitted in March by California Reps. Dana Rohrabacher and Mike

Honda that would allow American former POWs to sue Japanese firms in U.S.

state or federal courts for losses and injuries they suffered during the

time they were imprisoned and forced to work as slave laborers.

The bill focuses on two provisions of the 1951 Treaty of Peace with Japan,

informally known as the San Francisco Peace Treaty.

If it is made law, U.S. courts would be prohibited from interpreting Article

14 (b) to mean that the United States has waived claims by its nationals

against Japanese corporations. The courts also would be obligated to invoke

Article 26 of the treaty, known as the "most-favored-nation clause," and

recognize that since the treaty took effect in 1952, Japan has concluded

reparation settlements with at least six other countries on more favorable

terms than those accorded the United States.

A precursor to the bill was a law passed in California in July 1999 that

allows survivors of forced labor during World War II and their heirs to sue

in state courts the firms that used such labor in Axis-controlled territories.

The wording of the law is clearly aimed at firms that aided the Nazi regime,

but since the out-of-court settlement of Holocaust-related slave labor claims

-- last year, the administration of former U.S. President Bill Clinton mediated

an agreement under which German firms set up a $4.5 billion fund to compensate

former slave laborers -- the focus of its application has shifted toward

Japan.

Recourse to the law

The law was co-authored by Honda, then an assemblyman in the California State

Legislature. During his time in the lower chamber, the third-generation

Japanese-American lawmaker also successfully sponsored a resolution calling

on the Japanese government to issue a "clear and unambiguous apology for

the atrocious war crimes committed by the Japanese military during World

War II" and pay reparations. The resolution split the Japanese-American community

in California, with many fearing it would lead to a "Japan-bashing" backlash

on the scale that occurred during the late 1980s and early '90s, when Japan's

trade surplus with the United States was the bone of contention.

Honda, 59, told The Daily Yomiuri in a recent interview in Washington that

his motivation for introducing POW legislation at the state and national

level was based on his childhood experience as one of about 120,000 Americans

of Japanese ancestry who were forcibly relocated to internment camps in 1942

"just because we looked like the enemy."

Honda played an active part in the redress movement that led to the symbolic

payment by the U.S. government of $20,000 to former internees under the Civil

Liberties Act of 1988.

Fighting alongside him in this struggle to right a historic wrong was John

Tateishi, national executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League.

In a recent interview in San Francisco, Tateishi said he thinks his friend

of 25 years made a bad mistake by sponsoring the POW bill.

"I think it's a terrible bill for him to introduce," Tateishi said. "If this

bill passes, the two provisions that are being waived through this legislation

essentially say that all future treaties are meaningless -- that you can

waive provisions of peace treaties."

Honda disagrees. "In this country, people have the right to have their day

in court," he said. "It's a guarantee."

And that day may be coming sooner than he anticipated. 0n July 18, the House

of Representatives passed 395-33 a budget provision barring the State and

Justice departments from using taxpayers' money to file motions to block

slave-labor suits.

"This looks like it's going to happen," said Associate Prof. Uldis Kruze

of the University of San Francisco's Center for the Pacific Rim. "It means

the Cold War is over, and the U.S. Congressional leadership, more tied to

local feelings, no longer has to protect Japan from its past."

Dulles' realpolitik

Protecting Japan from its past was one of the aims of the architect of the

San Francisco Peace Treaty, John Foster Dulles. Having served as legal counsel

to the U.S. delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference at the end of World

War I, Dulles was determined that the treaty he brokered among the 48 nations

participating in the San Francisco Peace Conference would not contain provisions

as harsh as those set out in the Treaty of Versailles, of which French Marshal

Ferdinand Foch said presciently at the signing ceremony in 1919, "This is

not a peace treaty -- it is an armistice for 20 years."

Unlike the Versailles treaty, the treaty inked on Sept. 8, 1951 contained

no "war guilt" clause and limited reparations to be paid by Japan. With the

Cold War under way and a hot war raging on the Korean Peninsula, U.S. foreign

policy sought to mold Japan as a bulwark against communist encroachment in

Asia from China and Russia. In a quid pro quo deal, Japan agreed to ally

itself with the United States in exchange for a "soft" peace treaty. For

its part, in the 50 years since the treaty was concluded, Washington has

sided with Tokyo and Japanese firms whenever they have been named as defendants

in reparation suits.

Less than a month after the California restitution law was passed, Lester

Tenney filed a suit in the state seeking damages from Mitsui. But following

the submission of a "statement of interest" by the State Department, which

said that invoking Article 26 would be an "act of extreme bad faith," U.S.

District Judge Vaughn Walker threw out Tenney's case, which had been consolidated

into a class action lawsuit filed on behalf of six other former POWs and

25,000 families.

In his ruling on Sept. 21, 2000, Walker said, "While full compensation for

plaintiffs' hardships, in the purely economic sense, has been denied these

former prisoners and countless other survivors of the war, the immeasurable

bounty of life for themselves and their posterity in a free society and in

a more peaceful world services the debt."

When he read the judge's ruling, "I almost threw up," Tenney said; "To have

a jurist, a man on the bench, say such a thing -- it's disgraceful. I will

say this, for those friends of mine, my buddies who were on Bataan with me,

in Corregidor: We surrendered once, in 1942. We're not going to surrender

again."

The case is now on appeal.

State 'foreign policy?'

California, the only U.S. mainland state ever to have been shelled by the

Imperial Japanese Navy, has become ground zero in the World War II reparations

battle. Even before the legislation enacted by Honda and others in the late

1990s, the JACL, headquartered in the state, promoted the cause of the Asian

and European "comfort women" who were forced to provide sexual services for

Japanese servicemen during the war. While questions have been raised over

the constitutionality of moves on the part of a state to create its own "foreign

policy" concerning the interpretation of treaties concluded by the federal

government, there has been a trend in the United States since the war for

state courts to claim jurisdiction to hear cases brought by alleged victims

of violations of international law.

Concerning the POW bill, Uldis Kruze predicts that "the (George W.) Bush

State Department will twist some elbows in the Senate and argue that Japan

is still our key ally in the Pacific and necessary for balance against an

emerging China."

Tokyo University Prof. Nobukatsu Fujioka, founder of the Japanese Society

for History Textbook Reform, said he believes "the Japanese people would

never imagine that President Bush would sign such an unsuitable bill. All

the claims have been definitely settled by the peace treaty."

Fujioka, who believes Japan should stop apologizing for its wartime

transgressions, said the passage of the bill could trigger an anti-U.S. backlash

in Japan and conceivably even the filing of retaliatory suits for the atomic

bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the firebombing of Tokyo.

Asked to comment on the California law, which places the behavior of Japanese

corporations on a par with that of the Nazi regime, Fujioka said: "I don't

think Japan's wartime (behavior) is comparable to the Nazi crimes against

humanity. Japan never thought of eliminating a nation or a race, but

unfortunately, many people (conflate) Japanese wartime acts and Hitler's

crimes."

Not so, claims Kruze.

"Slave labor was slave labor, in Japan or Germany, no matter what the religious

beliefs of the oppressed were or weren't," he said. "What slave labor was

about was brutality and death -- for millions. It's a miracle that there

are still people alive today who can provide eyewitness testimony to the

brutalities of that type of inhuman treatment."

Kruze believes the Japanese firms named in reparation suits should follow

the lead of their European counterparts. "I would suggest that Mitsubishi

and the other corporations get a fund together and study what the Germans

did in their situation," he said.

But for Tenney, compensation is of secondary importance. "I want an apology

first," he said. "This is not about money. Our lawsuit is a lawsuit about

honor. It's a lawsuit about respectability. It's a lawsuit about responsibility."

Copyright 2001 The Yomiuri Shimbun

Source: http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/ties/ties023.htm

WWII POWs to get apology from Tanaka

Gaku Shibata

Yomiuri Shimbun Correspondent

September 9, 2001

SAN FRANCISCO -- Foreign Minister Makiko Tanaka, in a pair of speeches to

have been given Saturday in San Francisco was expected to praise cooperation

between Japan and the United States and apologize to former prisoners of

war for hardships they suffered during World War II.

Tanaka was expected to vow to strengthen Japan-U.S. cooperation over the

next 50 years in a speech at a ceremony to commemorate the 50th anniversary

of the signing of the Japan-U.S. security treaty, which is organized by the

Japanese and U.S. governments.

The foreign minister will stress that during the last 50 years, the Japan-U.S.

security treaty played a major role in maintaining peace in the Asia-Pacific

region and reveal a plan to increase security talks to strengthen the alliance.

At another ceremony to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the signing of

the San Francisco Peace Treaty, which is organized by the Northern California

Japan Society and The Yomiuri Shimbun, Tanaka will apologize to former U.S.

POWs.

Tanaka will speak about the incurable scars left on many people, including

POWs, by World War II.

By humbly accepting the historical facts, she was to echo the grave reflection

and sincere apology contained in a 1995 speech delivered by then Prime Minister

Tomiichi Murayama.

Copyright 2001 The Yomiuri Shimbun

Source: http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/newse/20010909wo42.htm

Japan apologizes to WWII prisoners

CNN.com

September 10, 2001

SAN FRANCISCO, U.S. -- Japan has marked the fiftieth anniversary of the treaty

ending World War II by apologizing to prisoners of war taken during the Japanese

march across Asia.

Though a Japanese prime minister made a similar apology in 1995, Foreign

Minister Makiko Tanaka's apology was the first such gesture on U.S. soil

that singled out POWs.

"The war has left incurable scars on many people, including former prisoners

of war," Tanaka said. "I reaffirm today our feelings of deep remorse and

heartfelt apology," Reuters news agency quoted Tanaka as saying.

Tanaka and Secretary of State Colin Powell spent the day shuttling between

commemorative ceremonies and meeting to discuss security and economic issues.

On September 8, 1951, delegates gathered in San Francisco to sign treaties

reinstating Japanese sovereignty and cementing a defense pact that remains

a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy.

"Our alliance is a living, breathing reality," Powell said in a speech at

the War Memorial Opera House, where the one-time enemies gathered to sign

the peace treaty.

"Japan is our Pacific anchor," he said.

Protesters demand more

Tanaka spoke before him, offering the carefully worded apology. Her statement

did not mollify members of Veterans for Justice, a group seeking reparations

from Japanese companies.

"'Deeply remorseful' is not saying, 'Hey, I apologize,"' said Lester Tenney,

who worked in a Japanese coal mine after his capture. "You know what, I am

deeply remorseful also."

Outside the Opera House, hundreds of protesters chanted, banged drums and

held signs calling for Japanese apologies and reparations.

They represented Chinese whose families were slaughtered during Japanese

occupation and Asian women forced into sexual slavery.

Under the San Francisco Peace Treaty, Japan was not required to compensate

the nations it attacked. American negotiators agreed to those terms because

they wanted Japan to develop as an ally against communism in East Asia.

Legal action

American POWs have sued Japanese companies, seeking compensation for their

forced labor.

The State Department has argued in U.S. courts that the treaty precludes

Japan from compensating American prisoners of war. Powell reiterated that

position to Tanaka over a working lunch.

"The treaty dealt with this matter 50 years ago ... it's a position we have

to defend," Powell told reporters. "At the same time, we have the utmost

compassion for these veterans."

Both sides hailed the treaties as remarkable economic and political successes.

Japan has become the world's second largest economy and an important U.S.

export market.

Despite a prolonged recession, Japanese firms have invested heavily in the

United States.

While the economic ties still bind, Japanese leaders have begun to question

other aspects of the relationship.

There is growing debate in Tokyo over revising the U.S.-written constitution

to loosen the limitation that Japan cannot field anything more than a

Self-Defense Force.

Japanese officials also increasingly criticize the U.S. military presence

on the island of Okinawa, where in June another in a string of servicemen

was accused of raping a local woman.

Powell said U.S. Marines on Okinawa must be better guests. Japan is host

to about 47,000 U.S. military service people under a separate treaty.

"We can always work to make the lives of our gracious hosts as little interrupted

as possible," he said.

© 2001 Cable News Network LP, LLLP.

Source: http://www.cnn.com/2001/WORLD/asiapcf/east/09/09/japan.apology/

American POW wants apology

from Japanese firms

Masayuki Kitano

Japan Today

October 16, 2001

Monday, October 15, 2001 at 09:30 JST TOKYO "He survived the Bataan Death

March and was forced to spend over two years shovelling coal in a mine operated

by a Japanese firm.

But more than half a century after his ordeal as one of Japan's prisoners

of war (POWs) ended, American Lester Tenney, 81, says he no longer harbours

anger towards the country or its people in general.

Instead, Tenney, who worked as a forced labourer from 1943 in the Mitsui

Miike mine operated by Mitsui Mining Co Ltd in Omuta, southern Japan, wants

an apology for the harsh treatment he received and to be paid for his work.

"These companies that beat us, didn't feed us and didn't give us medical

care. These are the ones that we are interested in. No one else," he said

in an interview in Tokyo.

Tenney was taken prisoner in the Philippines and survived the infamous Bataan

Death March of April 1942 before being sent to Japan in a cramped, disease-ridden

ship.

More than 36,000 U.S. soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen and civilian

construction workers are said to have been forced into slave labour in Japan

during the war. About 10,000 died in captivity and thousands more suffered

malnutrition and serious illness.

"I think it's time to get this thing over with," said Tenney, who was in

Japan to speak to college students and schoolchildren about his wartime

experiences.

Dozens of lawsuits have been filed in the United States seeking compensation

from Japanese firms.

But ex-POWs such as Tenney suffered a setback in September last year, when

U.S. District Judge Vaughn Walker dismissed a series of suits seeking reparations

for thousands of former U.S. and other Allied prisoners of war.

A suit filed by Tenney against Mitsui Mining, Mitsui & Co Ltd and their

U.S. subsidiaries was thrown out by Walker along with suits against other

major Japanese firms including Nippon Steel Corp and Mitsubishi Corp.

Mitsui & Co was named in Tenney's suit due to its pre-war ties to Mitsui

Mining, said Bonnie Kane, a lawyer representing Tenney.

Tokyo and Washington as well as Japanese firms such as Mitsui Mining have

maintained that claims against the Japanese government or nationals were

settled by the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, a position that Walker upheld

in his ruling.

Tenney appealed unsuccessfully against the federal court ruling. However,

Kane said she expects to file another appeal.

Apologizing and paying wages are the only things Japanese companies that

used POWs as forced laborers can do to make up for the past, Tenney says.

"In the year 2001, they can do nothing today about not having given us food,

about medical care, or about stopping the beating," he said.

A spokesman for Mitsui Mining said a "certain number" of Allied POWs were

used as laborers at the Mitsui Miike mine, which the company acquired from

the Japanese government in 1889 and stopped operating in March 1997.

"Our company provided a place for Allied POWs to work, but this occurred

under the jurisdiction of the military," said Mitsui Mining spokesman Minoru

Sasaki, adding that the company did not know the exact number of POWs who

worked in the mine.

Tenney says he was often beaten with a hammer or a pickaxe when he failed

to work fast enough to satisfy the Japanese operators of the mine.

He says he is not seeking a specific amount of money, and that receiving

an apology "to give us back our honor" is the most important thing for former

POWs.

In the wake of the court's rejection, an initiative to support POWs has emerged

in Congress.

Two Californian members of the House of Representatives, Republican Dana

Rohrabacher and Democrat Michael Honda, have proposed a bill that would let

former POWs pursue compensation in U.S. courts.

But strong opposition exists in some quarters, as reflected in an opinion

article written by three former U.S. ambassadors to Japan that appeared in

the Washington Post late last month.

Walter Mondale, Thomas Foley and Michael Armacost said they were "extremely

concerned" that Congress was considering passing legislation that would require

courts to entertain former POWs' lawsuits.

Such measures would undermine U.S. relations with key ally Japan, and have

"serious, and negative, effects" on national security by abrogating the San

Francisco Peace Treaty, they said.

The current U.S. envoy to Japan, Howard Baker, said he agreed with his three

predecessors.

"I can say that it will remain the position of the U.S. government that all

such issues were liquidated by the treaty itself," Baker said. (Reuters News)

© Reuters 2001

EDITORIAL

October 3, 2001

GI war claims

Clarence M. Graham, an

80-year-old World War II veteran, spent three-and-a-half years as a prisoner

of the Japanese. He was among tens of thousands of American GIs who wound

up as slave laborers in Japan. His worst experience was working in a condemned

coal mine near the city of Omuta, Japan.

"We were taken prisoners by the Japanese and were used as slaves, tortured

in various ways and maintained on starvation rations," Graham told Tom Brokaw,

who reported his recollections in The Greatest Generation Speaks.

"Many were murdered. Many died of diseases and starvation."

"It was very hot work, and very deep. The air was quite bad in there. The

dust was terrible because it was a soft bituminous coal, and it filled the

air and there were no currents and we had to breathe it. You had to keep

your wits about you to stay alive because one false move, and your life was

nothing in that country. They’d kill you in an instant if you disobeyed.

"I had a little belt on my waist, and all we wore was a loincloth. Sometimes

I got to coughing so bad that I would take off my whole wardrobe and wrap

it around my face so I could breathe." We had a cigar box with rice in it

and that would be our ration for a 12-hour shift."

Graham considered himself lucky, however, because, unlike some others, "I

had a battery light that didn’t leak on me and get acid on my skin."

Another GI, Lester Tenney, spent two years in a Mitsui coal mine,

working more than 12 hours a day on meager rations of rice and water, as

The Hill’s Melanie Fonder reported. In 1999, he sued the company, but

the U.S. State and Justice departments blocked the suit on the grounds that

it violated the U.S.-Japan peace treaty.

Last July, Graham, Tenney and other World War II veterans who were slave

laborers in Japan won a major victory when the House voted 395-33 to bar

the U.S. government from preventing them from suing Japanese companies for

reparations. Reps. Dana Rohrabacher (R-Calif.) and Mike Honda (R-Calif.)

are leading sponsors of the bill.

Last month, the bill was opposed by three former ambassadors to Japan: former

Vice President Walter F. Mondale (D-Minn.), former Speaker Thomas S. Foley

(D-Wash.) and Michael H. Armacost, now president of the Brookings Institution.

In a morally obtuse op-ed page article in The Washington Post, they argued

that such lawsuits were barred by the U.S.-Japanese peace treaty. They also

noted that Americans imprisoned by the Japanese were paid more than $90 million

in assets seized from Japan, which came to about $3,000 a prisoner, which

amounts to about $23,000 today.

Mitsubishi was among the biggest employers of American slave labor. Foley

is a member of a Mitsubishi Corporation advisory panel that meets once a

year to give strategic advice to the company. Although it is a paid position,

Foley assured The Hill that this role had nothing to do with his opposition

to the veterans’ lawsuit. He said he was merely supporting State Department

policy. Former Rep. Robert Michel of Illinois, who was the Republican leader,

has joined forces with the former ambassadors.

It is inconceivable that, as members of Congress, they would have supported

Japanese war criminals at the expense of former GIs.

The Japan-U.S. peace treaty indeed states that the signatories waived "all

reparations claims of the Allied Powers, other claims of the Allied Powers

and their nationals arising out of any actions taken by Japan and its nationals

in the course of the prosecution of the war." Steven C. Clemons pointed out

in an op-ed article in The New York Times that America’s principal

negotiator, John Foster Dulles, feared that heavy reparations burdens would

cripple Japan, make it vulnerable to communist domination and prevent it

from rebuilding.

However, Article 26 of the treaty states that, "should Japan make a peace

settlement or war claims settlement with any state granting that state greater

advantages than those provided by the present treaty, those same advantages

shall be extended to the parties to the present treaty."

Japan did, in fact, grant other states, including the Netherlands, the right

to have nationals sue Japanese corporations for reparations. Therefore, U.S.

veterans who were slave laborers also have that right, according to Article

26.

As for the argument that the veterans already had received $3,000 ($23,000

in today’s dollars), that hardly seems to compensate for their years

in hell. Why not let a judge and jury decide what constitutes adequate

reparation?

But the veterans are not only on solid legal ground (as if the State Department

had not looked the other way at innumerable breaches of laws and treaties),

they are also on high moral ground. It is nothing short of shocking to see

men who once occupied positions of great importance and trust in our government

opposing GIs who were victims of such atrocities.

The Senate should ignore those who pander to war criminals and give this

bill another veto-proof show of support.

POW Forced-Labor Lawsuits:

Four Years Later

by Kinue Tokudome

Translated from the Japanese monthly, Ronza, September 2003 issue

It has been four years since former American POWs filed lawsuits against

almost sixty Japanese companies, seeking an apology and back wages for their

wartime forced labor. After a series of pre-trial motions, these lawsuits

are still far from being resolved. This article chronicles the recent

developments surrounding these lawsuits and examines the issues that these

lawsuits present beyond their legal implications.

Developments in the Court

Pre-trial motions for POW forced-labor lawsuits have been made at both federal

and California state courts. Those cases which were heard by the federal

court were all dismissed in January of 2003 by the Ninth Circuit Court of

Appeals. It is reported that plaintiffs plan to appeal to the U.S. Supreme

Court.

At the California state courts, POW cases against Mitsui and Mitsubishi,

and a Korean-American case against Taiheiyo Cement, were both allowed to

proceed to the trial stage. The defendants filed a petition with the California

Court of Appeal to vacate the lower courts' decisions. The Taiheiyo case

was again allowed by the Court of Appeal to proceed in January of 2003 while

a different panel dismissed the POW case in February of 2003. Here are some

of the highlights of that ruling.

The Judge first wrote that this was a remarkable case. After having declared

that the Peace Treaty simply precludes this lawsuit from going forward, the

opinion devoted considerable space for the description of POWs' sufferings.

It explained, "The very process of explaining the effect of the treaty also

requires that we recognize the sacrifice of these plaintiffs. That sacrifice

deserves to be explicitly recognized by the judiciary of this country, regardless

of the validity of the legal claims they are now making..." It continued:

Most of the plaintiffs were taken prisoner in the spring after the surrender

of Bataan in April 1942. Then came the infamous "Bataan Death March," where

prisoners, most weak and ill, were prodded by bayonets to march in the tropical

heat for six days and nights without hardly any food and water. If they failed

to keep up they were run through.

The prisoners were eventually put into "hell ships" to be taken to Japan.

POW ships are supposed to be marked, so that one side does not attack its

own nationals. The hell ships, however, were unmarked, and in fact a number

were sunk by American submarines en route to Japan...

The conditions were horrendous, and bespoke gratuitous cruelty. The prisoners

were packed like sardines into hatches, which were always sealed; sick prisoners

could not get air...

Once in Japan, the prisoners were forced into slave labor for private Japanese

companies (usually mining) that supplied the Japanese war effort. As the

plaintiffs themselves now point out, the use of that forced labor was contrary

to clearly established international law regarding the use of the labor of

prisoners of war...

The experience of Frank Bigelow, a veteran of Corregidor, was typical:

"Everyday the Japanese Army delivered us to a coal mine owned by Mitsui...

We were told to work or die -- long hours, short rations. Usually, tiny portions

of rice and seaweed soup could barely sustain us as we were doing physical,

heavy labor. I was skin and bones, and at 6 foot, 4 inches, I weighed just

95 pounds."

There were constant beatings, which would increase whenever the United States

won an important battle. Over 11,000 of the 27,000 some Americans captured

and interned by the Japanese military during World War II died.

The California Court of Appeal, although describing POWs' sufferings in detail,

explained that the Peace Treaty waived their claims so as not to repeat the

failure of the Versailles treaty and to rebuild Japan and its economy as

quickly as possible. As for the individual claims, which POWs argued were

not waived, it said, "...even allowing POWs to pursue private claims against

the large Japanese companies who had exploited their labor would be ruinous

as well. An economy dominated by these 'zaibatsu' would suffer greatly if

they could be subjected to such claims."

Upon hearing this ruling, plaintiffs filed a petition for review with the

California Supreme Court. Although the Supreme Court very rarely grants such

a review, it granted review on April 30, 2003 for both the POW case and the

Taiheiyo case. Therefore, forced-labor lawsuits against Japanese companies

are back to square one after four years since the first filing. The main

focus of the review will most likely be on the constitutionality of the

California statute that made these lawsuits possible. It will probably take

6-12 months before the Court issues a ruling.

Developments Outside the Courts

On September 25 2002, House of Representatives Subcommittee on Immigration,

Border Security and Claims, Committee on the Judiciary held a hearing on

POW forced-labor lawsuits. Committee members asked the government officials

what actions the administration took since the joint resolution, which called

for the U.S. government to play a facilitating role in these lawsuits, had

been passed in December of 2000. William Taft, State Department's legal advisor,

answered:

We have been in touch with the Japanese Government and with some of the

companies, and I would have to say that we have not been encouraged... We

have not been encouraged that they are prepared to settle these suits...

We have tried to tell them that this is something that we would like them

to be more forthcoming on, but we have not gotten a response.

About this testimony by Taft, Japanese House of Councilors member Mitsuru

Sakurai submitted a written question to Prime Minister Koizumi in December

of 2002 asking, "Who from the Japanese side responded, and how and when?"

Prime Minister Koizumi responded in a written answer:

We have indeed been contacted by the U.S. side as Mr. Taft testified, but

I would rather not reveal the details of our exchange because they were of

diplomatic nature between Japan and the United States.

The U.S. media have been consistently sympathetic towards POWs. Just this

past June, Reader's Digest, which has a circulation of 17 million across

the U.S., ran an article entitled, "Vets vs. Uncle Sam: Don't make them fight

twice," written by CNN commentator Tucker Carlson. He chronicled the wartime

sufferings of Dr. Lester Tenney who is one of the plaintiffs in the

POW forced-labor lawsuits. He concluded, "Whoever has the strongest legal

case, it's clear who has the moral high ground..."

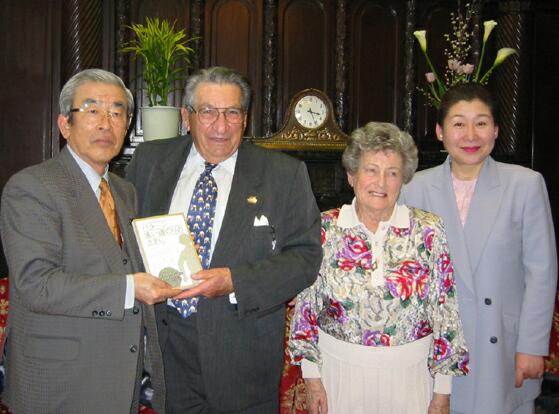

Dr. and Mrs. Tenney with Vice Speaker of the Upper House, Mr. Shoji Motooka,

and Upper House member, Ms. Tomiko Okazaki

Dr. Tenney has been featured in the U.S. media countless times and his enduring

spirits and humanity touched many hearts of American people. He has become

the poster boy of sort for all POW forced-labor lawsuits. His message of

reconciliation through "forgiveness" and "responsibility" reached Japan last

March. The Japanese edition of his memoir My Hitch in Hell was translated

by volunteers and published in Japan. During his visit to Tokyo on the occasion

of the publication of his book, he was greeted warmly by many Japanese people

including more than a dozen National Diet members. Dr. Tenney spoke in front

of them:

A Japanese industrial giant, a corporation, allowed its employees to physically

abuse me on a daily basis any time I didn't work fast enough, didn't work

hard enough, or if the Japanese lost an important battle. That experience

alone was, by far, the worst of all my experiences as a prisoner of war.

But we must learn to forgive, and those who committed these atrocities to

humanity must come forward and accept responsibility for their actions. I

hope that with dignity and responsibility we can continue building our future

together.

Copies of his memoir were presented to 200 members of the Japanese Diet who

belonged to the Foreign Relations and Security Committees of both houses.

Dr. Tenney also met Mr. Koichi Ikeda, a former Japanese POW who was forced

to work in Siberia after WWII and with whom he had exchanged emails. Dr.

Tenney embraced Mr. Ikeda telling him, "I know what you went through and

share your pain."

Questions that POW lawsuits pose for Japan

For the defendant companies, not only has the four years of legal battle

failed to bring a resolution to POW forced-labor lawsuits, but it has also

not improved their company image due to the media coverage on the lawsuits.

What questions do these developments pose for Japan? Is fighting these lawsuits

all the way by insisting that the Peace Treaty resolved the issue the best

course of action even if defendant companies can prevail in the court in

the end? Shouldn't Japan take these lawsuits as an opportunity to finally

start a process of "facing the past," not for the passive purpose of shedding

the image of a nation that does not learn from the past, but for the purpose

of actively reaching out to former victims of its past wrongdoings in order

to achieve reconciliation while the former POWs are still alive?

Recently, three persons enhanced my belief by sharing their own views.

The

first was my friend Mr. Clay Perkins, who offered to purchase 200

copies of the Japanese edition of Dr. Tenney's book. Having been deeply moved

by the original edition, he told me that I could use the 200 copies the way

I thought was best. When I let him know that we would donate them to Japanese

Diet members, he sent me a message to accompany with each copy. It read: The

first was my friend Mr. Clay Perkins, who offered to purchase 200

copies of the Japanese edition of Dr. Tenney's book. Having been deeply moved

by the original edition, he told me that I could use the 200 copies the way

I thought was best. When I let him know that we would donate them to Japanese

Diet members, he sent me a message to accompany with each copy. It read:

It has been fifty-seven years since the end of the war. Japan and the United

States have gone from bitter enemies to the best of friends. It is in that

new spirit that I address you -- as a friend. I want to share our common

history so that we can be closer as human beings.

I am proud to call Dr. Tenney my friend. In spite of his prison experience,

he bears no ill will against Japan or the Japanese people. I hope that you

too will find in this book his well-tempered faith in humanity.

Next, I attended the annual convention of the American Defenders of Bataan

and Corregidor held in Albuquerque this May. More than 300 former POWs of

the Japanese, most of whom are now in their 80s, were gathered there along

with their families. They reaffirmed their

determination

in fighting their legal battle against Japanese companies. There I met with

some of the children whose fathers were POWs and did not survive. One of

them was Mr. Duane Heisinger, a retired Navy captain, who just published

a book about his father entitled, Father Found. In it he chronicles

the life of his father who died on a POW transport "hellship." Captain Heisinger

searched for the former POWs who were with his father during the war, listened

to their stories, and "found" his father 58 years after his death. The voyage

of the particular hellship that his father was put into was one of the cruelest

-- only about 300 out of 1,600 POWs who were on board survived. Captain Heisinger

movingly described what his father might have said to his children with his

last breath. After I came home, he wrote to me: determination

in fighting their legal battle against Japanese companies. There I met with

some of the children whose fathers were POWs and did not survive. One of

them was Mr. Duane Heisinger, a retired Navy captain, who just published

a book about his father entitled, Father Found. In it he chronicles

the life of his father who died on a POW transport "hellship." Captain Heisinger

searched for the former POWs who were with his father during the war, listened

to their stories, and "found" his father 58 years after his death. The voyage

of the particular hellship that his father was put into was one of the cruelest

-- only about 300 out of 1,600 POWs who were on board survived. Captain Heisinger

movingly described what his father might have said to his children with his

last breath. After I came home, he wrote to me:

My desire is to find mutual understanding and perhaps reconciliation among

those of us, Japanese and Americans, who lost fathers during the WWII days,

by learning together more of the historic events. That is where my heart

is.

Lastly, I had an opportunity to exchange emails with Mr. Hampton Sides,

the author of Ghost

Soldiers

whose Japanese edition was just published by Kobunsha. His book on the rescue

mission of American POWs in the Philippines in 1945 became a bestseller in

the U.S. two years ago, and a Hollywood motion picture based on the book

will be released early next year. The book starts with a chapter describing

the Palawan massacre where Japanese soldiers herded 150 American POWs into

air raid shelters and burned them to death. Mr. Sides wrote to me: Soldiers

whose Japanese edition was just published by Kobunsha. His book on the rescue

mission of American POWs in the Philippines in 1945 became a bestseller in

the U.S. two years ago, and a Hollywood motion picture based on the book

will be released early next year. The book starts with a chapter describing

the Palawan massacre where Japanese soldiers herded 150 American POWs into

air raid shelters and burned them to death. Mr. Sides wrote to me:

I can only hope that my book will bring to Japanese readers a rich and vivid

sense of the times, and that it may also help explain why so many ex-prisoners

of Japan still harbor such intense animosity toward their captors. No one

in the United States should be allowed to forget what these men endured.

My book is in no way intended to be an attack on the Japanese -- indeed,

I spent four months living in Japan with my family researching the book and

had a fabulous and unforgettable experience and made many friends. But in

the end, I think the Japanese public will only benefit from knowing the truth

about how its army treated captives during the war.

Shouldn't we listen humbly to these people who are in no way anti-Japanese?

What they are trying to say is based on a deep human desire of "telling and

sharing the truth." It will never disappear even after the perpetrators win

in the court or all victims have passed away. It is fortunate for Japan that

former POWs express their willingness to forgive if their former captors

acknowledge the fact of forced labor and take full responsibility for it.

To refuse it by saying "they must be after money" is to deny their human

dignity yet again.

Achieving a meaningful reconciliation, however, requires the full disclosure

of historical records. Stuart Eizenstat, who played a central role in the

U.S. mediation between the German government/companies and their wartime

slave/forced-labor victims, wrote in his book, Imperfect Justice,

"I believe the most lasting legacy of the effort I led was simply the emergence

of the truth." He went on to write that at the encouragement of the U.S.,

twenty-one countries established historical commissions. Many countries decided

to squarely face their wartime histories and record them accurately for their

future generations.

But Japan still has not started such a task. The Japanese companies that

used POWs as slaves have yet to acknowledge their involvement and to open

their company archives. This is in stark contrast with efforts made by German

companies such as Volkswagen, whose history project includes opening the

company record on wartime slave labor to the public, building a memorial

within the company site, and publishing memoirs of victims. The excuse made

by some Japanese, "The Holocaust and what Japan did during WWII were different,"

sounds hollow.

Japan should also recognize how important it is for the victims that those

who were responsible for their sufferings acknowledge their wrongdoings and

offer a sincere apology. Eizenstat described a moving scene where German

President Rau acknowledged the sufferings of former slave/forced laborers

before them, begging forgiveness on behalf of the German people. One survivor

was so moved that he spontaneously leaped from the audience to the president's

microphone and cried, "This is what we wanted to hear." The Japanese government

and defendant companies will be well advised to think how much this exchange

meant not only to the victims, but also to the future generations of Germany.

Mr. Eizenstat wrote me saying that he agreed with the conclusion of the op-ed

piece I published in the Asahi Shimbun where I essentially wrote:

Now is the time for the Japanese defendant companies and the government of

Japan to recognize the historical fact of POW forced labor, offer a sincere

apology and try to find a way, through consultation with the U.S. government,

to compensate the victims.

Being a lawyer, he could not have agreed with my conclusion without realizing

its implication to the Peace Treaty. Congressman Christopher Cox, who strongly

opposed Congressional support for POW lawsuits, also wrote to me on one occasion,

"Voluntary compensation would not abrogate the San Francisco Peace Treaty."

Dr. Tenney recently told me:

What we need is for the Japanese Government, along with those Japanese companies

that used POW labor, to come forward and offer to share in a fund for the

benefit of all mankind, including the former POWs who were enslaved by the

various Japanese companies, through education and a lecture series. Education

and communication is the only way the countries of the world will ever be

able to get along.

Lastly,

the office of Senator Orrin Hatch, chairman of the Senate Judiciary

Committee, sent me the following message: Lastly,

the office of Senator Orrin Hatch, chairman of the Senate Judiciary

Committee, sent me the following message:

Chairman Hatch remains fully committed to continuing to fight for justice

for these POWs and continues to explore legislative options. We hope that

any obstacles we have encountered in past efforts will be surpassed, and

Chairman Hatch hopes to gain the necessary support from his colleagues on

both sides of the aisle to finally obtain justice for the victims of this

horrible ordeal.

True to his words, Senator Hatch introduced on July 17, 2003, a "Resolution

of Claims of American POWs of the Japanese Act of 2003," which would

authorize the U.S. Government to pay $10,000 to each surviving POW who

was held and forced into slave labor for private Japanese companies during

World War II. It passed in the Senate on the same day.

It is high time Japan should also make efforts to achieve meaningful

reconciliation by showing sincerity.

* Kinue Tokudome is a Japanese journalist who lives in Irvine, CA.

* Ronza is a Japanese monthly magazine published by the Asahi Shimbun.

* All photos used by permission.

High Court Rejects WWII POW Labor Case

By ANNE GEARAN, Associated Press Writer

October 6, 2003, 11:20 AM EDT

Read

full article here

The following articles deal with Chinese forced

labor during WWII and subsequent legal issues, and shed much light on

the background of the Japanese Government stance regarding POW compensation

over the last sixty years:

Page 1 INDEX

|