Treatment of Allied POWs and Civilian Internees in Japanese Camps During WWII

The treatment of Allied POWs and civilian internees by Japanese forces during World War II was marked by widespread brutality, neglect, and violations of international norms, such as the Geneva Convention (which Japan did not ratify for POWs, though it adhered to some Hague Conventions). Approximately 140,000 Western Allied military POWs and around 130,000 Western civilians were held, with death rates for POWs reaching 27-40% due to starvation, disease, forced labor, and abuse—far higher than in European theaters. Conditions varied by region and camp commandant, but common features included overcrowding, inadequate food and medicine, grueling work, minimal recreation, and frequent physical punishments. Civilian internees, often including women and children, generally faced slightly less severe labor demands but similar deprivations. Below is a detailed breakdown by region, drawing from historical accounts.

The Philippines

In the Philippines, major camps like Camp O’Donnell, Cabanatuan, and Bilibid Prison held tens of thousands of American and Filipino POWs following the 1942 surrenders at Bataan and Corregidor, alongside civilian internees in places like Santo Tomas University in Manila. Living arrangements were primitive: at O’Donnell, up to 60,000 POWs were crammed into a former Philippine Army base with bamboo barracks lacking walls or roofs in many areas, leading to exposure to monsoon rains and extreme heat. Overcrowding fostered disease outbreaks like dysentery and malaria, with death rates peaking at 400-500 per day in the early months; overall, about 26,000 of 45,000 POWs died there from neglect.

Work was mandatory and exhausting, including burial details for the dead, farming, and infrastructure repairs, often under brutal guards who beat prisoners for perceived slowness. At camps like Palawan (Camp 10-A), POWs built airfields barefoot in loincloths, crushing coral by hand and pouring concrete without tools, facing executions for complaints. Recreation was virtually nonexistent, limited to clandestine card games or storytelling to maintain morale amid constant abuse.

Food rations were meager—typically a handful of poor-quality rice daily, infested with weevils, leading to severe malnutrition and beri-beri. Red Cross parcels arrived sporadically but were often looted by guards, with one rare distribution in 1944 stripped of medical items. Medicine was absent; prisoner doctors improvised with scavenged materials, but untreated injuries and diseases claimed thousands. Civilians at Santo Tomas (about 4,000, mostly Americans) fared slightly better initially, self-organizing into committees for sanitation and education, but endured similar starvation and disease, with children particularly vulnerable. Atrocities escalated later, culminating in massacres like Palawan’s December 1944 execution of 139-150 POWs by burning and machine-gunning in trenches to prevent liberation.

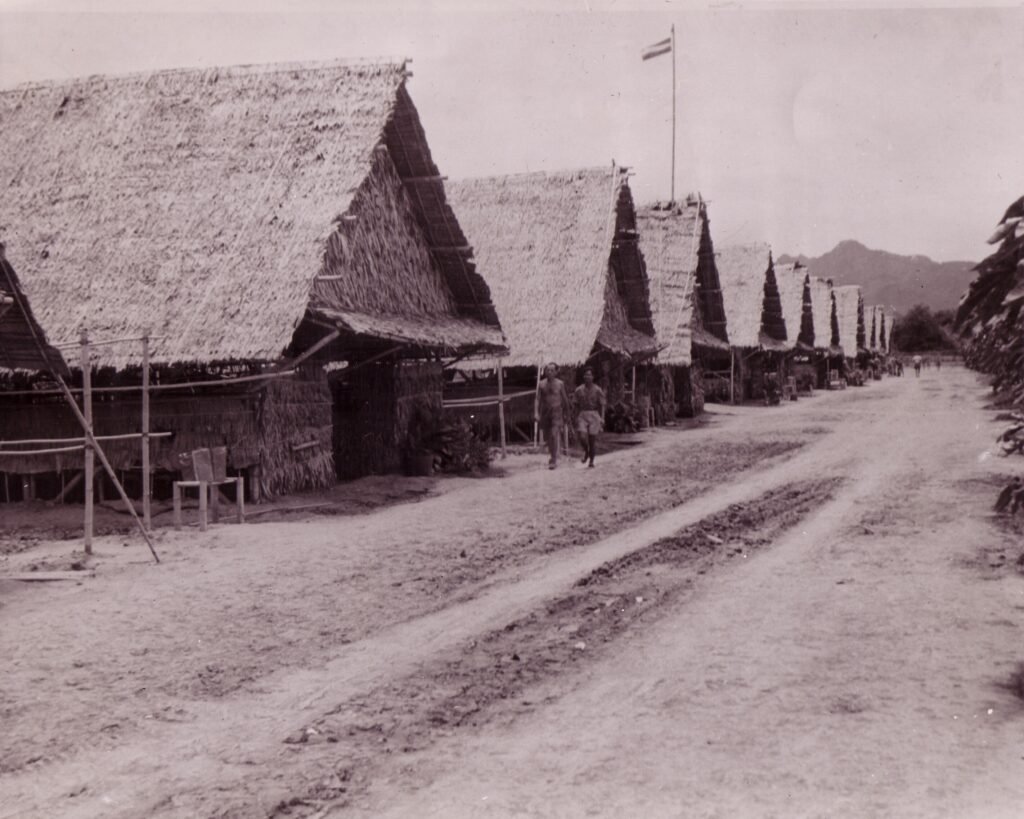

Southeast Asia (e.g., Singapore, Malaya, Thailand, Burma)

SE Asia camps, such as Changi in Singapore and those along the Burma-Thailand “Death Railway,” housed British, Australian, Indian, and other Commonwealth POWs, with civilians interned in nearby facilities like Sime Road. Living arrangements at Changi involved overcrowded former British barracks, with up to 50,000 in spaces meant for far fewer; subcamps like Selarang saw 15,900 crammed into a small parade ground without toilets or water for days as punishment. Conditions were unsanitary, with open latrines breeding flies and disease.

Work dominated life: on the Death Railway, 60,000 POWs (including 16,000 who died) labored 12-18 hours daily building tracks through jungle, using hand tools amid monsoons, with “speedo” periods enforcing faster paces via beatings. Recreation was sparse but inventive in better-managed camps like early Changi, where POWs organized concerts, libraries, and classes under self-administration.

Food consisted of watery rice stew with occasional vegetables, often rotten, causing widespread malnutrition; prisoners bartered with locals or grew gardens when possible. Red Cross parcels were withheld, exacerbating starvation. Medicine was improvised by POW doctors using bamboo for splints and tins for tools, but tropical diseases like cholera and ulcers killed many; in railway camps, outbreaks led to rapid deaths. Civilians (e.g., 20,000-30,000 British and Australians) in camps like those in Singapore faced gender-segregated housing in schools or warehouses, with minimal work (camp maintenance) but high disease rates; death rates matched POWs at 10-30%. Atrocities included the Sandakan Death Marches in Borneo, where 2,500 POWs were force-marched through jungle, with survivors executed—only 6 escaped.

Indonesia (Dutch East Indies)

Camps in Java, Sumatra, and Borneo held about 42,000 Dutch POWs and 100,000-110,000 civilians (mostly Dutch Eurasians, women, and children), in sites like Tjihapit (14,000 internees) and smaller outposts. Living arrangements used repurposed buildings like hospitals or prisons, often segregated by gender; overcrowding led to squalor, with camps surrounded by bamboo fences and guards.

Work for POWs involved airfield construction, farming for Japanese forces, or mining; in Sumatra, Australian nurses were forced to grow food for guards while starving. Recreation included smuggled concerts or religious services in civilian camps to preserve normality.

Food was critically deficient—rice portions shrank to starvation levels, with prisoners resorting to grass or ferns; on Ambon, 80% died from hunger as parcels were refused. Medicine was nonexistent, leading to rampant malaria, dysentery, and beri-beri; nurses traded belongings for smuggled drugs. Civilians endured higher death rates (13-30%), with women managing child care amid brutality; internment lasted until 1945, complicated by post-war Indonesian independence conflicts. Transports on hell ships to Japan or elsewhere added to mortality, with overcrowding and sinkings claiming thousands.

Mainland Japan

Mainland Japan hosted over 100 camps, separated into command groups such as Sendai, Tokyo, Nagoya, and Fukuoka, holding about 25,000 US and other POWs transferred via hell ships for industrial labor; civilians were fewer, mostly in urban internment sites. Living arrangements featured wooden barracks in industrial areas, often unheated in winter, with thin mats on floors; camps like Naoetsu (Tokyo Branch #4) were notoriously brutal, with 8 guards later hanged for crimes. Overcrowding and poor sanitation prevailed, exacerbated by air raids.

Work was intense and hazardous: POWs labored in mines (e.g., Omine, Kinkaseki in Formosa but similar in Japan), steel mills, shipyards, and factories for companies like Mitsui and Mitsubishi, often 10-12 hours daily without pay, violating conventions. At Fukuoka #1, prisoners mined coal amid cave-ins and gas explosions; beatings were routine for quotas. Recreation was minimal, though some camps allowed hidden diaries or shared stories; punishments for such included torture.

Food rations were scant—rice balls and weak soup, leading to weight loss of 50-100 pounds; Red Cross parcels were rare, with many receiving only one over 3.5 years. Medicine was withheld; at Mukden (though in Manchuria, similar to Japanese camps), suspected experiments like live dissections occurred without anesthesia. Diseases thrived due to no supplies, with prisoner medics improvising. Atrocities included executions under the Enemy Airmen’s Act for captured flyers and mass killings to prevent rescues. Civilians faced detention with disability compensation post-war for resulting illnesses. Liberation in August 1945 brought air-dropped supplies, but many camps like Fukuoka #24 saw prisoners take over amid chaos.

So… how many camps were there now?? Read this summary, POW and Civilian Camps throughout the Japanese Empire.

Sample Camp Report

PRISONER OF WAR CAMPS IN JAPAN & JAPANESE CONTROLLED AREAS AS TAKEN FROM REPORTS OF INTERNED AMERICAN PRISONERS

LIAISON & RESEARCH BRANCH AMERICAN PRISONER OF WAR INFORMATION BUREAU

by JOHN M. GIBBS – 31 July 1946

FUKUOKA CAMP NO. 17

ON THE ISLAND OF KYUSHU, JAPAN

1. LOCATION:

Omuta, on the bay, about 17 miles northwest of Kumamoto and 40 miles south of the city of Fukuoka, opened on 7 August 1943. The coordinates are 33 N, 130 25’E. Terrain level, well drained and filled in with slag from a coal mine at Omuta. Dimension of original camp site, 200 yards square which by April 1945 had been enlarged to 200 yards wide by 1,000 yards long. The site is a reclaimed grove and the buildings thereon were formerly laborers quarters constructed by Mitsui Coal Mining Co. and operated by Japanese Army. A wood fence approximately 12 feet high with 3 heavy gauge wires (first wire approximately 6 feet off the ground) enclosed the compound. The grounds were kept as clean as possible at all times. Some fir trees adorned the compound. The Japanese officials were stationed in the enclosure.

2. PRISONER PERSONNEL:

Maj. A. C. Tisdell, spokesman; Maj. Thomas H. Hewlett, camp surgeon and Maj. John R. Mamerow, medical officer.

Camp first occupied 10 Aug. 1943 by 10 officers, 133 NCO’s and 358 privates, a total of 501, all Americans, from the Philippines. 497 American prisoners from the Philippines reaching the port of Moji, Kyushu on 29 Jan. 1945, were divided among the Fukuoka area installations as follows:

100 to camp #3 located at Tobata

193 to camp #1 located at Kashii

110 to the Japanese Military Hospital at Moji

95 to camp #17

Only 34 of the hospital prisoners, later transferred to No. 22 survived. The death of the 76 prisoners while in the hospital was due to the horrible conditions of travel from the Philippines to Moji, and extreme malnutrition.

An earlier group of 200 American prisoners from the Philippines reached Moji on 3 Sept. 1944 all of whom were assigned to camp #17, making a total of 814 American prisoners, which was the maximum. The camp was liberated on 2 Sept. 1945. There were 1721 prisoners in the camp toward the closing of it on 2 Sept. 1945. British, Australian, Dutch and American prisoners evacuated the last minute from the Philippines and Siam were in desperate physical condition when they arrived.

3. GUARD PERSONNEL:

Asao Fukuhara, Camp Commandant

Camp surgeon, an unnamed Japanese Army man

Civilian guards, 2 pseudo named as the “sailor” & “one arm bandit”, both Japanese.

There were Japanese orderlies who worked as hospital attendants, number and names unknown.

4. GENERAL CONDITIONS:

(a) Housing Facilities:

The barracks comprised 33 one story buildings 120′ x 16′ with 10 rooms to a barracks, of wood construction with tight tar paper roofs, and windows with panes. Ventilation satisfactory. Three to 4 officers were billeted in one room 9′ x 10′ and 4 to 6 enlisted men in room of same size. No heating facilities, and while the climate was mild, it must be remembered that the men were sensitive to temperatures around 40 Fahrenheit, and because of their weakened condition due to malnutrition the dampness and cold was very penetrating. The barracks were light enough during the day without artificial illumination. Each room had one 15-watt light bulb.

Air raid shelters were dug into the earth about 6 feet deep and 8 feet wide, 120 feet in length, timbered in similar manner, to coal mines, covered with 3 feet of slag and an adequate splinter-proof roof.

The beds consisted of tissue paper and cotton batting covered with a cotton pad 5’8″ long and 2½’ wide. Three heavy cotton blankets were issued by the Japanese in addition to a comforter made of tissue paper, scrap rags and scrap cotton.

(b) Latrines:

In each of the 33 buildings, and at the end thereof, were 3 stools raised from the floor about 1½’ on a hollow brick pedestal, each being covered with a detachable wood seat, and 1 urinal. A concrete tank was underneath each stool. The prisoners made wood covers for each of the stools, thereby reducing the fly nuisance. The offal in the tanks was removed by Japanese laborers twice each week.

(c) Bathing:

The bathing facilities were in a separate building equipped with 2 tanks approximately 30′ x 10′ x 4′ deep, with very hot steam heated water. The American camp spokesman would not permit the men to immerse themselves during the summer months on account of skin diseases. In the winter the tubs were used but not until the men had taken a preliminary bath before entering the tubs. The men were required to watch each other to see that none “passed out” because of the heat and their weakened condition. After bathing the men would dress in all the clothing they had and go to bed for the night. Even then the prisoners would fill their canteens with hot water and place them beneath the covers. With these precautions the men slept comfortably through the cold nights.

Each 2 barracks had an outside wash rack, 16 cold water faucets and 16 wood tubs with drainboard. Prisoners washed their cloths by scrubbing with brushes on the drainboard and rinsing them in the tubs. There was a constant shortage of soap.

(d) Mess Hall:

There was 1 unit mess with 11 cauldrons and 2 electric cooking ovens for baking bread, 2 kitchen ranges, 4 store rooms and 1 ice box. Cooking was done by 15 prisoners of war of whom 7 were professional cooks, all working under the supervision of a Japanese mess sergeant. The men working in the coal mines were given 3 buns every 2nd day to take with them for their lunch when they did not return to the camp to eat. Other days they were given an American mess-kit level with rice. Prisoners ate in the mess hall in which was placed tables and benches.

(e) Food:

Usually consisted of steamed rice and vegetable soup made from anything that could be obtained, 3 times a day. Upon occasion of a visit to this camp by a representative of the Red Cross in April 1944 a splendid variety of fats, cereals, fish and vegetables were served, which naturally impressed the representative and in his report to headquarters, he called particular attention to the menu. It is known that the spread was to impress the Red Cross man, and that it was the only decent meal served in 2 years. Rice and soup made from radishes, mostly water, remained the diet throughout. The men working in the mines were given 700 grams of rice, camp workers 450 and officers 300. Our American camp doctors stated that such scant ration was insufficient to support life in a bed patient. All of the prisoners were skeletons having lost in weight an average of around 60 pounds per man. The city water was drinkable.

(f) Medical Facilities:

Medical section and surgical section of infirmary had 10 rooms each with capacity of 30 men each. Isolation ward could accommodate 15 men. Daily medical and dental inspections by American officers, but they had but little to work with in the way of medicines and instruments. The dentist had no instruments and could only perform extractions, and without anesthesia. For dysentery the Japanese furnished a powder which they concocted, the use of which produced nausea and diarrhea when administered to the American patients. There were no American hospital corpsmen in this camp until April 1944 when 10 men were added to the hospital corps with 2 doctors and 1 dentist. After Oct. 1944 medical supplies were provided and an operating room installed. Prior to Oct. 1944 the camp was practically without medical supplies. The Japanese doctor was entirely disinterested.

(g) Supplies:

(1) Red Cross, Y.M.C.A., other Relief: The first Red Cross and Y.M.C.A. supplies were received early in 1944 on the Japanese ship TEIA MARU. The items in the food parcels were doled out to the men sparingly provided he had a consistent work record in the coal mine and was not guilty of infractions of rules. In the aggregate each man was given the equivalent of about 1 complete parcel during the full period of his confinement. The favoritism shown the mine workers in the distribution of parcel items defeated the intention of the Red Cross because it tended to give protein foods to the more healthy rather than to the weak. The 1944 Red Cross shipment contained medicines, surgical instruments and other supplies which the Japanese refused to make available for the benefit of the invalided men, but helped themselves to them. The Y.M.C.A. furnished several hundred books.

(2) Japanese Issue: The clothing (cotton) was issued by the coal mine company and was adequate. British overcoats were given out by the Japanese Army. Each prisoner was given 3 heavy cotton blankets and a comforter madeof tissue paper and scrap rags and scrap cotton. The canteen was practically bare. From it the men received regularly 5 cigarettes per day. Canned salmon could be bought about each 2 months, 1 can per man.

(h) Mail:

(1) Incoming: First incoming mail was received in March 1944, thereafter each 60 days.

(2) Outgoing: Prisoners were allowed to write a card about each 6 to 8 weeks.

(i) Work:

In coal mines and zinc smelters 3 shifts per day of approximately 100 men per shift. Conditions in the mines were pronounced dangerous although only 3 men were killed outright during the period of confinement of 22 months. Many men received painful injuries from falling rocks and other causes. Fortunately for the prisoner there was among the group an experienced coal miner who gave the men safety talks and pointed out some of the dangers of coal mining which were not apparent to novice workers. The coal mines were operated largely by American prisoners, the smelters by the British and Australian prisoners. Coal mines were approximately 1 kilometer from camp. Hours of work 12 hours per day, 30 minutes lunch time. The men were given one day off every 10 days.

(k) Treatment:

From time to time the men were beaten without cause with fists, clubs and sandals. Failure to salute or bow to the Japanese was an offense which usually was followed by compelling the prisoners to stand at attention in front of the guard house for hours at a time. Some men were beaten daily and others harassed by guards while trying to sleep during their rest time.

(l) Pay:

(1) Officers: Were paid 20 yen per month until June 1944 when it was increased to 40 yen less 18 yen per month for mess. Each prisoner received 5 cigarettes per day regularly except for about 1 day per month. Postal savings accounts for officers deposited with Protecting Power amounted to 7,688.26 yen. Prisoner of War Headquarters ran its own destitute welfare.

(2) Enlisted Men: NCO’s were paid 14 sen per day and privates 10 sen per day. No postal savings were deposited with Protecting Power.

(m) Recreation:

The Y.M.C.A. provided equipment for such out-door games as football, volleyball and tennis, but the prisoners, at the close of work periods, were too tired and weak to play. There were no indoor sports except those made by the prisoners. There was a rotating library of about 300 volumes provided by the Y.M.C.A. A vegetable garden was planted and maintained by the prisoners, and some live stock was raised, but the Japanese ate the live stock and none of it was made available to the prisoners.

(n) Religious Activities:

In July 1944 a protestant Dutch Army Chaplain arrived as one of a prisoner detail. Until his arrival the camp was without a chaplain. From July 1944 protestant services were held each Sunday.

(o) Morale:

Was low primarily because of inadequate food, long and hard working hours which left no time except for work and sleep. There was no laughter, no singing, nothing but depression which condition was made worse by beatings and the harassing activities of the Japanese guards during the sleeping hours.

5. MOVEMENTS:

Of the group of 501 officers and enlisted men which reached this camp in August 1943, 15 died. The remainder left for Mukden, Manchuria on 25 April 1945. Other American prisoners, approximately 340 remained at Camp No. 17 until liberated on 2 Sept. 1945.

[NOTE from Roger Mansell: Caution! The Gibbs reports were prepared post-war based upon assorted prisoner affidavits and, apparently, on the reports of the International Red Cross representatives in Japan who were notorious for their bias in favor of the Japanese.]

japanpow(at)use.startmail.com

Copyright 2001-2026, Wes Injerd. All Rights Reserved.