Discovery of Allied POW and Civilian Internee Camps

The locations of many Japanese-run POW and civilian internment camps in Japan, the Philippines, Southeast Asia (including Singapore, Malaya, Thailand, and Burma), and Indonesia (Dutch East Indies) were gradually uncovered through a combination of Allied intelligence efforts, aerial reconnaissance, escaped prisoners, and local resistance networks during World War II. By mid-1944, as Allied forces advanced in the Pacific, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and other intelligence agencies had compiled lists of known camps based on radio intercepts, debriefings of escaped POWs (such as those from the Bataan Death March or hell ships), and reports from Filipino guerrillas or Dutch resistance in Indonesia. For instance, camps in the Philippines like Cabanatuan and Los Baños were pinpointed through guerrilla intelligence and aerial photos, enabling targeted raids. In Japan proper, where over 100 camps held about 25,000-30,000 Allied POWs by 1945, locations were identified via B-29 reconnaissance flights and signals intelligence, though exact conditions remained unclear until surrender. Civilian internee camps, housing around 130,000 mostly Dutch, British, American, and Australian non-combatants (including women and children), were often in urban areas like Santo Tomas in Manila or Tjihapit in Java, discovered through similar means but with added input from neutral diplomats or the International Red Cross, which had limited access. In remote areas like Borneo or Sumatra, some camps remained unknown until post-surrender surveys, with RAPWI (Recovery of Allied Prisoners of War and Internees) teams facing challenges in locating an estimated 350,000 captives across vast, war-torn regions.

Liberation Efforts by Allied Forces

Liberation varied by theater and timing, with immense efforts involving coordinated military operations, often under urgent conditions to prevent massacres as Japanese forces retreated or faced defeat. In the Philippines, early liberations occurred through daring raids amid ongoing combat. For example, on January 30, 1945, US Rangers and Filipino guerrillas rescued 486 POWs from Cabanatuan in a nighttime assault, trekking survivors to safety amid Japanese pursuit; only two rescuers died, but the operation highlighted risks from malnourished prisoners unable to march far. Similarly, the February 23, 1945, raid on Los Baños freed 2,147 civilians and POWs using amphibious vehicles and paratroopers, with minimal casualties but requiring immediate medical evacuations.

Japan’s unconditional surrender on August 15, 1945, triggered widespread liberations across Japan and Southeast Asia. In Japan, US forces under General Douglas MacArthur prioritized rapid occupation; B-29 bombers and naval task forces identified and secured camps starting August 29, with ground troops from the Eighth Army landing at Yokohama to liberate sites like Yokohama and Naoetsu. POWs witnessed atomic bomb effects (e.g., Nagasaki’s flash on August 9), signaling imminent freedom. In Southeast Asia, British-led South East Asia Command (SEAC) under Lord Mountbatten executed Operations Birdcage (leaflet drops urging safe surrender) and Mastiff (for POW recovery), though Mastiff focused more on Europe; instead, RAPWI coordinated efforts from August 15, deploying teams to unknown camps amid logistical chaos. Singapore’s Changi was liberated on September 5 by the 5th Indian Division, including Gurkha units, who secured the camp and provided immediate aid to emaciated prisoners. In Indonesia, liberations were complicated by the Indonesian independence struggle, with some internees held in “recovery camps” for months post-surrender. Efforts involved thousands of troops, medical personnel, and ships, with challenges like disease outbreaks, Japanese non-cooperation, and terrain.

Emergency Supply Drops by Parachute

To avert starvation in the interim between surrender and ground liberation, Allied forces launched massive airdrop operations, expending significant resources on aircraft, packaging, and coordination. Starting August 27, 1945, US B-29s from Guam and Okinawa dropped over 4,000 tons of food, medicine, and clothing to 154 known camps in Japan, China, and Korea, using improvised “storepedos” (welded oil drums) or parachute-fitted kit bags. Drops included Red Cross parcels with bully beef, sugar, and warm clothing, crucial for weakened prisoners facing winter. In Southeast Asia, British and Australian aircraft conducted similar drops under RAPWI, though less reliable due to monsoons and remote locations; for example, at Changi, parcels arrived post-surrender rumors, easing tensions. These operations saved thousands from imminent death but faced risks like inaccurate drops or injuries from falling containers.

Well-Organized Recovery Efforts and Repatriation

RAPWI, activated August 15, 1945, orchestrated recovery with teams of medical officers, nurses, and administrators fanning out to camps, providing on-site care and evacuations. In Japan, POWs were processed at airfields like Atsugi, with nurses and medics assessing health; severely ill were airlifted, others shipped home. Repatriation involved hospital ships like USS Benevolence and troop transports; Australians, for example, sailed from Yokohama or Manila in September-October 1945, with 14,000 returning by boat after sheltering from typhoons. In Singapore, Gurkhas reunited emotionally before shipping to Dehra Dun, India, by late September. Civilians in Indonesia faced delays, some held until 1946 amid conflicts. Identification used camp rosters, fingerprints, and debriefings; war graves units like the Australian War Graves Group reburied deceased at sites like Yokohama Cemetery. Efforts repatriated over 100,000 by late 1945, though some lingered in recovery camps.

Incidental Note on Long-Term After-Effects

A great number of liberated POWs and internees never fully escaped the shadows of their ordeal, suffering lifelong physical ailments like chronic malnutrition-induced heart disease, gastrointestinal issues, and weakened immunity, alongside psychological scars such as PTSD, depression, and anxiety—studies 40 years post-war showed former POWs significantly more depressed than controls, with higher rates of alcohol abuse and impulse control problems. These effects rippled to families, manifesting as intergenerational trauma through strained relationships, economic hardships from lost years, and inherited health vulnerabilities, often compounded by societal stigma or inadequate veteran support.

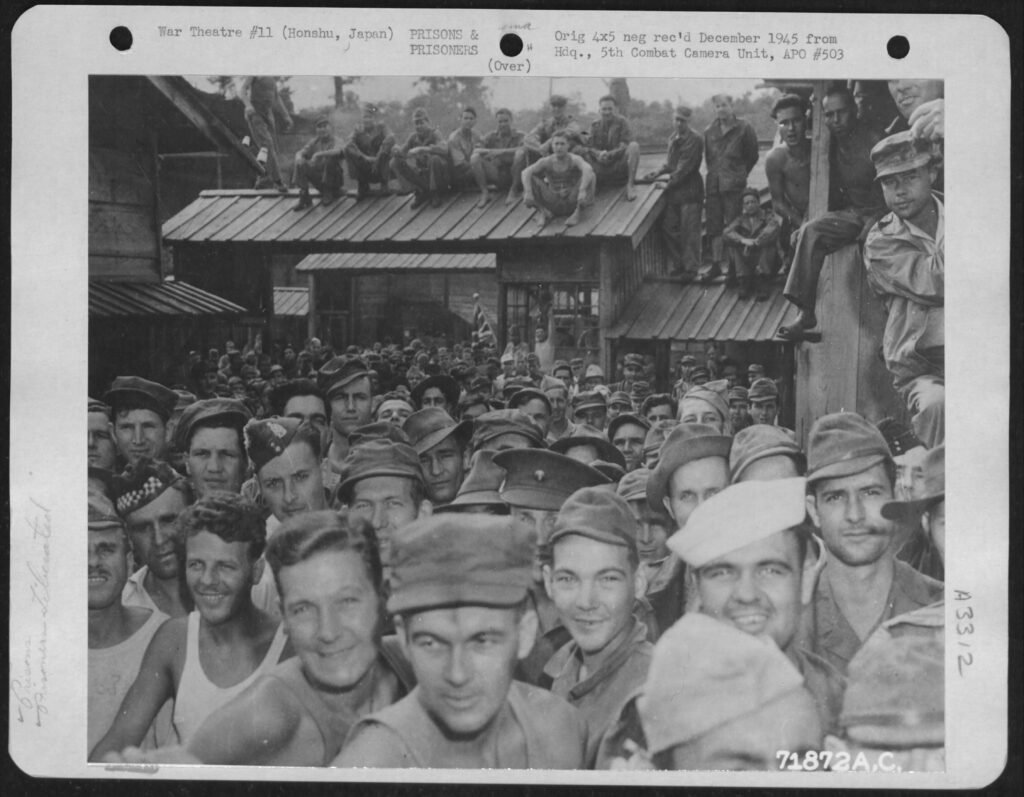

“An indescribable scene of jubilation and emotion…”

“Their faces express the emotions of these overjoyed G.I.’s, for they now know their dark days have come to an end.”

The excitement of the prisoners was a never-forgettable sight. As has been said, many of them were unclad, some clad merely with a G-string, others with trunks, while some others were dressed in non-descriptive apparel. They carried home-made improvised national flags of the United States and Great Britain.

Commodore Boone preceded the group along the pipe-line and was ashore first. Obviously it gave him the distinction of being the first American ashore in the environs of Tokyo. This fact was an after-thought because the scene was one of such intense emotion that no one could be mindful of distinctive conduct at the moment. Everyone was motivated by an impulse to get ashore and lend every effort in the relief of the starved and suffering Allied prisoners of war.

— Commodore Boone and the Liberation of Omori and Shinagawa camps, Aug. 1945 (Task Group 30.6)

“Approximately 250 white prisoners wore observed in the encampment and on the roof waving wildly.”

“A total of about 150 persons were observed on the ground waving joyously.”

“… discovered signs at Sendai camp #2 indicating that the POW’s there needed cigarettes and food.”

“Prisoners of war at all camps seemed jubilant at seeing our planes.”

— USS Belleau Wood Reports, Aug. 1945

“The missions were unusually successful in spite of inclement weather and all camps in the area were supplied with some of the necessities and comforts of life. It was evident by the elation of prisoners shown in photos that the immediate appearance of carrier aircraft raised the moral of allied prisoners of war.”

— Task Group 38.1 Report

“Commander Task Group 30.6 with a medical and evacuation party… proceeded to the Omori Camp number 8, which was known by intelligence to be Tokyo Headquarters Camp. The appearance of the landing craft in the channel off the prisoner of war comp caused an indescribable scene of jubilation and emotion on the part of hundreds of prisoners of war who streamed out of the camp and climbed up over the piling. Some began to swim out to meet the landing craft. After some difficulty in being heard, the prisoners of war were assured that more boats would be coming and that they should stand steady for an orderly evacuation, and that the liberation party wanted to go immediately to those who were ill and extend medical assistance and evacuate them first.”

“Information was obtained from Commander MAHER and other POW officers that there were many seriously ill at a POW camp called Shinagawa hospital. CTG 30.6 determined to evacuate this hospital as soon as possible… This party completed its mission and returned with the report that inspection of Shinagawa revealed it to be an indescribable hell hole of filth, disease and death.”

“All personnel performed in an outstanding and exceptional manner, responding to the acute need and the obvious urgency of fast action to extend medical care to those in need of it and to avoid an eruption from the extreme tension thot existed in the camps. Boats crews, ship’s personnel, evacuation teams, processing teams, and commanding officers worked long, consecutive hours with cheerfulness and efficiency and with obvious satisfaction of playing a part in the relief of human suffering.”

— Task Group 30.6 Report, Aug. 29, 1945 (later commended for “rapidly releasing and efficiently caring for approximately 20,000 Allied Prisoners of War”)

“The rescue and repatriation of United Nations prisoners of war became urgent and acute coincident with the signing of the terms of surrender on 4 September 1945. The great hue and cry created by the distressing conditions noted among the first recovered Allied military personnel elevated to the highest priority evacuation of all prisoners… Their physical condition was so poor that it became necessary to examine and to screen them on the assumption that all were ill.”

— Fifth Fleet Report

First On Board – USS Haven, Sept. 11, 1945

“At 1900, the first ex-prisoner of war was admitted to the USS HAVEN’s Hospital from the Japanese Army Hospital at Nagasaki. Three other ex-prisoners of war, a Dutchman, and Englishman, and an American, had been able to get to the USS HAVEN from Fukuoka #2 Japanese Prison Camp and were admitted to the Hospital.”

— Task Group 55.7 – USS Haven Report

“On Sept. 23, the Rescue arrived back in Guam, and after discharging a few prisoners whose home had been on Guam, she proceeded on her triumphal voyage to San Francisco where her repatriates saw the United States again for the first time in years and realized that the dream which kept them alive many grim months had at last come true.”

— Task Group 30.6 – USS Rescue Report

From heaven did the LORD behold the earth;

To hear the groaning of the prisoner;

to loose those that are appointed to death.

Psalm 102:19-20

For further study:

What, Where and When We Knew About the Existence and Location of POW Camps Around Fukuoka, Japan

Finding Our POWs – The Recovery and Evacuation of POWs from Japan, Aug.-Sept. 1945

Recovery and Rescue of Prisoners of War, September 1945

The Liberation of POW’s, Sept. 1945

The Evacuation of POWs in 1945 by United States Navy Hospital Ships

japanpow(at)use.startmail.com

Copyright 2001-2026, Wes Injerd. All Rights Reserved.