The Sheboygan PressFriday, January

28, 1944

JAP ATROCITIES

|

SENSATION

- February 1943 issue

|

||||

|

|

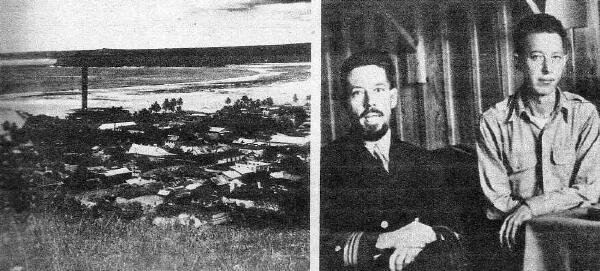

| PEACEFUL SHORES of Guam were the battlefields where the Nips landed in their treacherous attack. | SCENE AT ZENTSUJI: Seated in Jap war prison are two Navy men. They look worn, thin. |

The Japs gave a repeat performance next day, Tuesday. By this time our nerves were steeled against the sound of explosions and the screech, thud and detonation of shells. I noticed then for the first time how almost unconcernedly we took the enemy barrage of bombs and shells. One grows accustomed quickly to the horrors of war and it makes for a general informality.

Someone once wrote -- it was Quentin Reynolds, I think-- that the "wounded don't cry." Ours didn't. With characteristic American grit they grinned at us, wisecracked a bit. I know it made my task a lot easier.

The Japs operated on schedule that day, bombing us three times. During each lull in the bombing I could hear the distant sound of gunfire.

About four o'clock Wednesday morning I was awakened by thunderous explosions. It wasn't a bombing attack. That I knew, for I had already learned by this time the difference between the sound of a bursting bomb and that of an exploding shell. This, I was sure, was the latter. It appeared to be quite some distance away ceaselessly for about an hour. Just about the time I reported at the hospital at five o'clock the thundering stopped.

There were several new patients at the hospital, among them an American, his native wife and her brother. They had been shot -- and bayoneted. The bayonet wounds meant only one thing. The Japs had landed on Guam.

"Jap soldiers have landed," the man gasped. "They shot us, then attacked us with bayonets. They left us for dead. There are swarms of them all over the island."

While I was giving first aid to the two men and the woman, the stillness of the early morning was shattered by a shout, followed a moment later by a terrific burst of machine gun fire directly outside the hospital gates.

Instinctively I dropped to the floor. Then I turned to look. Everyone had done likewise. We literally hugged the floor for at any moment a shell might come crashing through the building or machine gun bullets crack through the windows or walls.

The air was heavy with explosions. Machine guns rattled an accompaniment. Evidently the whole town was under fire. But our own guns were answering the challenge. Gradually the savage cracks cease and the sudden stillness is quiet as startling as the barrage.

I think: How many dead and dying lie in their homes or in the streets? Can our pitifully small garrison repel the invasion? Will aid be sent in time? Is this what has happened in Hawaii? On the floor some of us were whispering words of encouragement, some are sitting up, others standing. The gunfire had ceased. Is the danger over?

Whatever I expected to hear, or see next, whether the screech of shells, the rattle of machine guns, the bursting of bombs or the rush of Jap soldiers through the hospital gates, I did not expect that which I heard -- the sound of an automobile horn.

It burst upon us with sudden furry. What it was for I could not imagine, but it blared away unceasingly for perhaps six to eight minutes, then stopped. I looked at others in the room in search of explanation but their wonderment was as great as mine. Word came then for us to return to our quarters. We didn't ask why. A Navy nurse obeys orders.

Hardly we had reached our rooms when the hospital gates were swung open and several hundred Japanese soldiers spilled through and swarmed over the grounds. From my window I saw them rush in, shouting and gesticulating wildly. They scrambled for the shade of trees, dropping their packs and guns as they flopped to the ground. And then they did an amazing thing. They produced bamboo fans and started fanning themselves. It was almost laughable.

IT was then that I received word that Guam had surrendered.

That long blast of the automobile horn was the signal for capitulation by Captain George Johnson McMillan, Governor of Guam.

My feelings? I ask any American to describe them. I was a prisoner of Japan!

At ten o'clock that morning we were told to return to duty. The Japs were told to return to duty. The Japs were in control of the hospital, and we were to take care of our own patience only. Later that order was countermanded and the Jap doctors took full charge, aided by their own hospital corp men. These latter were merely boys, trained more or less haphazardly in the duties of nursing.

From my window that afternoon I saw a sight I never want to see again. I have seen the dead and the dying, men horribly wounded and torn. I have never flinched at that. But that afternoon I saw the Stars and Stripes hauled down.

For one awe-inspiring moment the flag fluttered in the breeze. The next, it sagged a bit and then disappeared from view. I couldn't see all that was happening, but I heard the crash of drums and the blare of bugles. The ropes on the flagstaff were moving again. The Japanese flag was hoisted to the top and the breeze whipped it out -- the cruel blood-red emblem of the Rising Sun on a background of white.

It was a sad and sickening sight. I wept. Those who watched with me cried unashamedly.

We soon learned what it was like to be prisoners of the Japs. Twice a day in the morning and evening we had to report for roll call. Probably because we were confined to our quarters and the immediate grounds around them, we were not molested, but our armed guards gave us little privacy.

They would enter our rooms whenever they so desired. Occasionally they would chat with us in English and it was English that was well-spoken and well-delivered. Often they would bring parties of sightseers to inspect our room. The sightseers were new Jap arrivals, mostly navel men.

There was no respect for personal possessions. When it prompted our guards to do so they walked into our rooms, opened our desks, bureau drawers and trunks and took what they wanted. Cigarettes and clocks seemed their particular desire, although they seized anything that took their fancy.

During the first few days I saw and heard of no acts of barbarism or brutality. But soon afterward I began to hear stories of atrocities throughout the island -- of attacks on women, of the bayoneting of men and children.

I was forced to undergo but one ordeal. Whenever I met a sentry or an officer I was compelled to bow. That command applied to all of us. At first some of us only nodded. That seemed to annoy the Nips and we were called back and made to bow sufficiently low to please them.

"You are not bowing to the sentry or to me" an officer explained, "You are bowing to the Emperor, you are now a conquered people."

How confident they were of victory. A Jap naval officer inspecting our rooms one day told us smilingly that the Japs had captured Hawaii and Manila, that our entire fleet had been sunk.

"Soon," he added with that sibilance so characteristic of the tongue of his nation, "we shall have occupied Singapore. Then the war will be over. Japan will be an all-conquering nation."

One morning I saw a group of our officers march by. They were heavily guarded. I thought then that they were being taken aboard a boat for Japan and an internment camp. Several hours later they returned. I had ways of obtaining information and I learned that the officers had been unwilling spectators at Jap maneuvers.

That experience was to be mine several days later. Together with my four nurses, a group of American sailors and some civilians, we were summoned to the hospital grounds and told that we were going to witness maneuvers. None of us wanted to go. We were forced to attend.

I stood by silently while the Japs paraded the captured American equipment -- guns and trucks. Then while they deployed in offensive formation, an American flag, probably the one that I had seen hauled down, was placed on a hillside. A cocky little Jap officer barked commands. Rifles and machine guns started firing at the target -- the flag. Within a few seconds it was torn to shreds. The Japs grinned and smirked. But they were not yet finished. They hauled out a particular looking instrument operated by several men. Apparently they wanted to impress us with the variety and quality of their machines of death. It was a flamethrower and the Japs took almost childlike delight in its operation.

Christmas and New Year's were hardly merry or happy occasions though I tried to lighten the burden. The days were passed mostly in recollection and in apprehension. Were the Japs going to keep us here indefinitely? Was it true about Hawaii, Manila and the fleet? I cautioned against pessimism.

ON January 10 I received the dreaded order. We were to pack and be ready to leave. Where? The officer smiled blandly. He didn't know. We were limited to a few personal possessions -- what were left -- and our clothing. My nurses and I remained together and when we appeared for roll call we were assigned our place in the line of march. All of us were prisoners, and among us were many American civilians whose native families were to be left behind.

We rode in a truck on top of our baggage for about six miles to a small port. Far out beyond the reef lay a huge ship. That told us that the worst had come. We were going to be shipped to an internment camp. To Japan? To one of the mandated islands? One guess was as good as another.

The boarding was tiresome. Small launches took us to the steamer.

As I climbed aboard I turned to take a last look at Guam, but smirking Japanese guards ordered me to move on. I climbed down into the hold of the ship. It was dark and musty. The porthole of the cabin to which I was assigned was covered and I was under strict orders not to attempt to remove the covering.

I counted noses. There was myself, Mrs. Jackson, Miss Yetter, Miss Fogarty and Miss Christiansen. And we had two newcomers, Mrs. Ruby Hellmers and her six-weeks-old daughter, Charline [Charlene]. Mrs. Hellmers was the wife of a petty officer in the Navy. He, too, was aboard the ship, but the Japs would not permit him to be with his wife or child. [See photo of four nurses and the Hellmers.]

Fortunately. I had been told that Mrs. Hellmers and her baby would accompany us and I had managed to obtain a nursery basket from the hospital. Otherwise there would have been no place for the infant to sleep. There were just four bunks in the cabin -- four bunks for six women and a baby. We agreed quickly. Two of us would have to sleep on the floor, alternating each night. We tidied up the cabin, arranged our belongings and waited, endlessly it seemed, for the ship to sail. But when at length it did I was seized with a new fear.

This was a Japanese ship. As such, it was a target for our American planes and warships. Would it be bombed or shelled, perhaps sunk? United States planes or ships would have no way of knowing that the ship carried American prisoners of war. I confided my fears to my companions. They had similar thoughts. That fear remained with us constantly. We were not concerned then so much with our unknown destination and our problematical fate as we were with the fear that the ship would be bombed or shelled or sunk.

Adding to our desolated spirits was, the food. We were served rice twice a day, occasionally with a bit of fish. For breakfast we had two pieces of bread and a liquid that might have been either coffee or tea but tasted like neither. It was scarcely a sustaining diet, no less a nourishing one.

I counted the days. Each day was becoming increasingly colder. From that I assumed we were traveling northward. Toward Japan? I didn't know.

The coldness penetrated our cabin and chilled us, but somehow the mustiness remained. It seemed to cling to the walls with apparent unfriendly determination. Since we were not permitted to open the porthole we kept the door ajar for ventilation. Every so often the guard, who stood with a bayonet-fixed rifle just outside, would stick his head through the aperture, count us and then pull back his head like a jack-in-the-box. That guard had a penchant for looking in at us at wrong moments. It was disconcerting, to say the least.

Late on the fifth day after we sailed from Guam we felt the ship slowing down. I sensed a feeling of impatience among the officers and guards. They barked commands and the conversational tome which they had used during the voyage was dropped suddenly. I was cautioned by the guard outside our cabin to await orders. My first thought was that we were going to be transferred to another ship. Then came the word. We were going ashore.

I think my courage then was at its lowest. It was the infectious smile of Mrs. Hellmers' that gave it buoyancy. I think now that perhaps she was the bravest of us all. We nurses were alone, but Mrs. Hellmers had a six-weeks-old infant daughter to care for and a husband whom she might never see again. Even now I marvel at her conduct, her genuine optimism that everything would turn out all right. And when the order was given to appear on deck, she picked the infant from her basket, wrapped the baby warmly and stepped from the cabin.

Flanked on either side by heavily armed guards we remained on deck until it was dark. It was bitterly cold and the wind cut through our tropical clothing. Mrs. Hellmers shivered and I took off my Navy cape and draped it over her shoulders.

Off in the distance toward the east, shore lights flickered. We were apparently in a port of considerable size. Small boats ploughed shoreward and we could see that some were covered with snow and ice. Much later, when we were ashore, I was told that it had been snowing that day. Small wonder it was so desperately cold. We were near famished, too, having eaten nothing since seven o’clock that morning -- the usual two slices of bread.

The cold was becoming numbing and I wondered how much longer we were going to be forced to endure it. Then the scow arrived, mooring fast to the ship. We marched aboard and were taken immediately to the wheelhouse. There, for the moment, we were sheltered from the biting, cutting wind.

A pitchy darkness surrounded us. I saw the ship fade out into the night as the scow churned through the rough and choppy water. Some minutes later we landed on a dock swarming with soldiers, sailors and what looked like police. Although we didn't know it, we were in Japan!

Once ashore the Japs wasted no time. Everything had been pre-arranged. The five of us and the infant were bundled into an ambulance that jounced and jolted for at least six to eight miles and then braked to an abrupt stop. There was little formality now. We stepped from the ambulance and were led to what seemed to me to be an enormous soldiers' barracks, and indeed it was. Weak from hunger and cold we almost stumbled our way in.

MY first impression was heart rending. The barracks, fully 250 feet long, was divided into many compartments. We were assigned to one of them. The beds were extremely narrow scarcely two feet wide, and hard as wood. The straw mattresses served no purpose what so ever, but we dropped upon them out of sheer exhaustion.

I reached the point of utter desolation that night. Even the brave Mrs. Hellmers faltered. The kaleidoscopic events of the day had drained our strength into nervous exhaustion. What we wanted most was food and warmth and sleep. The barracks were miserably frigid.

Then from somewhere an officious little Japanese bustled up. He brought us soup, cabbage soup, tasteless but hot. It was far from satisfying but its warmth sent us to sleep.

To the best of my recollection we arrived at the camp on January 15 and for almost two months we faced the ordeal and privations of the temporary alien camp in Zentsuji on the island of Shikoku, one of the larger islands of the sprawling Japanese archipelago.

Remember, it was mid-winter and winters in Japan are severe as we soon found out. Our barracks were not heated and the charcoal pots, later replaced by a small coal stove, provided little warmth. Our blankets were of synthetic material, and to keep warm at night we went to bed fully dressed even to our coats and gloves.

I had succeeded in inducing one of the attendants to rearrange our beds, explaining that they were too narrow for comfort or for rest. A small wooden platform was built and the straw mattresses were placed side by side, and in six-in-a-bed fashion. We slept, not always comfortably, it is true, but at least more warmly than would have been the case had we slept alone. Charlene, the baby, remained trundled in the nursery basket and under real blankets that I had taken from the hospital at Guam.

Food, what there was of it was far from nourishing. At first we received soup and rice three times a day. Later the menu -- I grace it by that name -- was changed to vegetable soup. There was no meat and no salt. During the fifty-odd days that we were at Zentsuji we received eggs twice and fruit three times. Occasionally we were honored by receiving a small loaf of bread.

At that, I think the women fared far better than the men. I know for certain that our quarters, bad as they were, were luxurious in comparison to those of the male prisoners. In the same barracks there were rooms for men. Forty enlisted men were assigned to one room, ten to 12 officers to another. Communication with them was forbidden, and the Japanese soldiers took particular delight in issuing orders to the Americans.

Toward the end of February I noticed for the first time that the faces of my companions were becoming drawn and thin. Experiences such as we had shared cannot help but sear an individual. This was something more than that. It was under-nourishment. All of us were beginning to lose weight. Our vitality was ebbing fast. Our transfer to the new internment camp at Kobe came just in time.

I left Zentsuji with no misgivings. Whatever fate lay before us at Kobe could hardly be worse than Zentsuji. It wasn't for when we arrived on March 12 it was as if we stepped back into the sunlight. To begin with, the camp was comparatively new and our room decidedly larger and warmer. And there was a noticeable lack of soldiers. Here, the police were on guard.

Here the food was better. There was meat, vegetables, butter, milk and eggs. Not every day of course, but far more frequently than we had thought possible. Salt was still a scarcity and sugar was rationed to a teaspoon a day. Here, too, without explanation we were free at last from the constant and embarrassing practice of guards entering our room. I wondered why. This sudden transformation was almost incredible of belief. I didn't know the reason then. I do now. Sooner or later, there would be an exchange of prisoners. The Navy nurses and Mrs. Hellmers would undoubtedly be among those to be exchanged and when we got back to America, the Japs would want no stories of privation, brutality, and barbarism.

The guards were almost courteous. Several times, under police escort of course, we went for walks through the streets of Kobe, and twice we were permitted to go on shopping trips.

In the camp were many nationalities -- Dutch, Scotch, British, Canadians, Guatemalans and ten Catholic priests, two of whom were subjects of Spain, who were released later with profuse and profound apologies.

There was an incessant flow of rumor, much of it so wild as to be utterly unbelievable. We discussed these reports briefly among ourselves, for the recurrent topic was how the war was progressing and, what our chances were of being rescued. Naturally we, received, only such items of news as the Japs wanted us to receive. Always they were the same -- Japan had won another great victory at sea, Japan had conquered the East Indies, the United States fleet was now all but destroyed. We didn't believe these statements but we couldn't challenge them.

IT remained for Jimmy Doolittle to answer them for us -- with bombs.

To say I saw the raid would be, an exaggeration. I saw one plane on that April morning but I heard many. It was close to noon when the American bombers dropped over the city of Kobe. From my vantage point at the window I could see the one plane swoop down low, its glass-like nose pointing earthward. It was not extremely high. The funny part of the whole thing was I didn't recognize it as an American plane. From any distance beyond several hundred feet, particularly when a plane is in the air, the U. S. Army insignia, the star in a circle can be mistaken easily for the Japanese insignia. In fact, there was so close a resemblance that the Army changed its markings by eliminating the star with in a circle.

My first intimation that Kobe was being bombed came when I heard several loud explosions, followed almost immediately by the wail of sirens. Faint columns of smoke arose at scattered points over the city.

Was it an American attack? I reasoned it was. Japan was not at war with Russia for we certainly would have been told that. Nor could the planes have been Chinese. British, perhaps, but far more likely American. To me, and I can speak for my friends also, those bursting bombs sounded awfully good. I was filled with pride that America was striking back, taking the war directly to the heart of the enemy, launching the offensive.

What damage the American raid caused I cannot tell for I have no way of knowing. I believe it must have been extensive for the Japanese were considerably less cocky after that. Not until days after were we told that it was a raid by American planes, but with the announcement was a strong hint of retaliation.

There was, at our camp, a police officer, Isumida, who was in charge of immigration before the war. He spoke a perfect English and he frequently talked with us. He had lived in the United States for 25 years. It was his Americanization, perhaps, that made him appear more human, more of a gentleman, than the rest.

It was he who summoned us to his office one morning in June. He smiled graciously.

"I have good news for you," he said. ”You are going to be exchanged as prisoners of war."

Is it necessary to describe our reactions?

Several days later we were taken by train to Yokohama. It was early morning and we had had no breakfast. We were taken to Tokio [Tokyo] for that. When we got back to Yokohama there was little delay. Within a half hour we were aboard the ship Asama Maru.

Then -- something happened. The ship did not sail that night or the next morning or the night after that. There were wild rumors -- negotiations had broken down, the exchange of prisoners was all a trick. Each day brought new desperation and fear. Would we be taken back to Kobe? Were we destined for another camp? If the negotiations for the exchange had been broken off would we face a new ordeal at Zentsuji?

For eight days the Asama Maru lay in the harbor at Yokohama and it seemed as if the entire activity of the port was centered around it. Japanese officials climbed aboard and left, then came back and left again. I saw our Ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew, confer with them and then they would bustle away.

It was exactly one-thirty in the morning of June 25 when the whistles of the Asama Maru shrieked and the anchor chains rattled. The propeller screws churned and the ship slowly turned toward sea. Ambassador Grew had obtained comfortable cabins for us -- the same six women and the infant, now seven months old, who had remained together constantly since our departure from Guam. The ship stopped at Hong Kong, at Saigon and at Singapore. Naturally, there was no shore leave, and in each port the ship anchored far enough off shore so that none of us could see the cities.

At Mozambique we parted company with Virginia Fogarty, one of my nurses. She was married there to Frederick Mann, former Vice Consul at Osaka, Japan.

It was at Mozambique, a Portuguese colony on the southeastern coast of Africa, that we exchanged, ships. We boarded the liner Gripsholm which was to take us home. Above the huge lettering Gripsholm was the word DIPLOMAT which was to assure the ship immunity.

The rest of that voyage home is anti-climax. We traveled 20,000 miles to get back into the United States and when, on that morning of August 29, I saw again the Statue of Liberty and the towering buildings of New York I knew it was the most glorious moment of my life.

There was one peculiar incident in connection with our arrival. Each of the nurses received a Christmas present, the long-delayed gifts which the Navy had intended to deliver to us at Guam.

My experience is that of hundreds of other Americans who are in Japanese hands today. From what I have learned since then I consider myself fortunate that I was spared the horror that others have faced and are facing.

It is an awful thing to be in their hands. That experience has seared my memory. Even now I sometimes wake up believing I am still in the Camp at Zentsuji or Kobe.

Don't underestimate the Japs. They are tough and tricky and possess a fanatical desire to conquer the white man. We are fighting for our very lives.

I am continuing the fight against them. I am now stationed at the United States National Naval Medical Center at Bethesda, Maryland. When and if we're called to take up posts at the firing line we'll be ready.

I'll be glad and willing to go anywhere I'm ordered. A Navy nurse always follows the flag.

(The opinions and assertions of Miss Olds' article are solely the writer's and are not to be construed as official or reflecting Navy Department policy. Editor's Note.)

AMBASSADOR GREW SPEAKS

"The Japanese Are Tough"

The

story of Navy Nurse Marion Olds is more than just a first-hand account

of life in a Japanese war prison. It is in itslef a challenge to

America to wake up to the fact that in the Japanese it is meeting a

tough, tricky and resourceful foe. Miss Olds' story is but one of the

many corollaries to the account given to the American people by the

Honorable Joseph C. Grew, former United States Ambassador to Japan,

when he returned from the semi-feudal, half-barbarian nation last

August.Miss Olds says that she herself saw no acts of brutality of barbarism, although she heard of many. Ambassador Grew gives direct evidence of terrible atrocities. His radio address to the American people on August 30, 1942, entitled, "The Japanese Are Tough," follows. SENSATION reprints it with the hope that it will help reawaken Americans to the yellow peril across the Pacific. EDITOR'S NOTE.

[The article, "The Japanese Are Tough," has not been transcribed yet. However, you may read the LIFE magazine article of December 7, 1942, for Grew's Report From Tokyo: An Ambassador Warns of Japan's Strength.]