Journal American

'I realized the Japanese were people.

I couldn't hate them'

Cecil Parrott's Memorial Day message has two parts. First, never forget those

who are serving. Second, forgive your enemies.

He knows from experience.

It was late 1942 and Cpl. Cecil Parrott, USAAC, was dying. Amoebic dysentery,

beri-beri and starvation had taken him from a lean 165 pounds to a cadaverous

97. With next to no medicine, his comrades at Camp O'Donnell POW compound

in the Philippines could do little more then put him in the "Zero Ward,"

a crawl space under the barracks where they sent men to die.

Every morning, Parrott would wake up with yet another dead man next to him.

"I noticed that the night before a guy died, he would talk about how abandoned

he felt, how he was convinced no one cared, that his family had forgotten

him. Not me. I would get home to my family," he said.

Armed with faith in the love of his family, Parrott did survive. He actually

saw his family again the day the war ended. By this time, he was working

as a slave laborer in the coal mines at Omuta, near Nagasaki.

Stricken by dysentery again, he was too sick to hear the camp commandant's

announcement that the war was over. But he could see his family clearly,

as if in a snapshot: his mother, brother and sisters. But not his father.

Couldn't figure out why. Later, he found out his father had died a few-months

before.

Parrott has ample reason to hate his enemies. When American and Filipino

troops surrendered at Bataan on April 19, 1942, Parrott was among them. The

troops had been on one-third rations for more than a month and were showing

the effects of malnutrition.

Then began the Bataan Death March. The Japanese marched the survivors some

70 miles up the Bataan Peninsula. In addition to being sick and exhausted,

the Allies had no food. Water consisted of what they could drink from the

fetid tropical streams along the way. The Japanese shot or bayoneted men

for whatever reason they pleased.

"I saw men bayoneted for trying to get a drink. I decided that dying of thirst

was preferable," Parrott said.

A friendly face

By the fifth day of the march, Parrott was too weak to keep up. As evening

came, he saw someone waving at the group of stragglers he had joined. It

turned out to be a Japanese soldier, a cook who had worked on merchant ships

before the war. He'd been to the United States and spoke good English.

He gave the men some boiled rice and fish, not much because he didn't have

a lot to give. One fact historians often forget to mention about the Luzon

Campaign is that the Japanese were nearly as short of food and water as the

Americans, Parrott said.

He also gave them some cigarettes and, most important of all, boiled green

tea with sugar. Parrott thinks that tea, the only clean water he had during

the march, probably save his life.

Armed guards were approaching, so the cook sent the Americans on their way.

His parting words: "I hope you get home to your families."

"So I realized the Japanese were people. I couldn't hate them. It was an

important lesson for me," Parrott said.

It helped him survive. Because he didn't hate the Japanese, Parrott could

observe and analyze them as individuals. It proved invaluable. Among other

things, it helped him communicate with some of the Japanese civilians who

worked at the Omuta coal mines.

He found they often were treated as savagely as Allied prisoners and hated

the Japanese army just as much. As a result, they would pass on bits and

pieces of news about the war, including the fact that, by early 1945, American

B-29s were leveling Japanese cities at will. It gave Parrott reason to hope.

On Aug. 19, 1945, the first American troops arrived at Omuta. They fed the

prisoners, gave them medical care and generally got them ready to go home.

Things were happening so fast, however, that Parrott and his colleagues had

to wait for a couple of weeks. With nothing to do, they occasionally walked

to the nearby town. They were surprised to find the Japanese gracious and

friendly.

One day, Parrott was walking down main street when a young woman invited

him home for lunch. Parrott was happy to accept. She served a delicious chicken

casserole, giving it all to him, taking none for herself, even when he insisted.

He never found out the reason for the meal.

"We should never forget the sacrifices Americans have made in war," Parrott

said. "But we also should remember the point of it all: peace and brotherhood

among all peoples."

The Seattle Times

YOUTHS HELP ORGANIZE EVENT HONORING POWS

REDMOND

By Steve Johnston

Seattle Times Eastside bureau

January 12, 2000

Cecil Parrott was barely out of his teens when he was captured by Japanese

soldiers in the Philippines, only slightly older than the Eastside high-school

students who yesterday put on a program to honor him and a dozen other former

prisoners of war.

Parrott, now 79, was one of the thousands of military and civilian personnel

taken prisoner after the Japanese army overran the Philippines in 1942 and

started them on the infamous 55-mile Bataan Death March.

He was captured April 9, 1942, and released more than three years later outside

a small city in Japan, where he had been forced to work in a coal mine. He

didn't know Japan had surrendered a week earlier until a U.S. soldier showed

up at the camp and told the prisoners they were free.

Parrott, now a Bellevue resident, weighed 163 pounds when captured and 97

pounds when released. He said he spent years overcoming the POW experience.

"I was a mess," he said. "I couldn't be confined in a house for more than

30 minutes before wanting to run out. I had nightmares."

Bruce Luce, an 18-year-old senior at Redmond High School, hasn't had any

experiences to match what Parrott and the other former POWs event through,

hut he felt a kinship with the men wearing the distinctive maroon jackets

that marked them as ex-prisoners.

Luce's grandfather, Wendell Luce, was a POW during World War II after his

B-17 bomber was shot down over Germany.

"I never realized how hard it was on my grandmother to have my grandfather

held prisoner," Luce said. "She received a telegram saying he was missing

in action, but nothing else."

Luce was happy to volunteer to help put together a program with the Lake

Washington post of the Veterans of Foreign Wars to honor the former POWs.

Twelve of the men present yesterday were WWII prisoners; the other was captured

during the Korean War.

"I thought it would be a good idea to have the students know what these men

event through," Luce said.

Working with Redmond High School's Student Leadership Program, Luce and

classmates Sarah Summerhays and Hunter Hargraves organized the program at

the Redmond VFW post.

"Once the kids got involved, they took over the program," said John Kenny

of the VFW. "Redmond sent us three kids, and they did it all."

At the ceremony yesterday, U.S. Sen. Patty Murray

said the WWII veterans, who included her father, were "America's greatest

heroes but also America's most silent heroes."

The men, now in their 70s and 80s, each received Congressional Merit certificates

from Murray. The luncheon ceremony included a student musical program, a

poem by one of the students and a video put together by students showing

news footage of wars.

ARIAKE SHINPO (The Ariake Daily News)

May 1, 2000 Monday, page 7

"No bad memories of life as a POW"

Former US soldier, Parrott, stands at old POW camp site after 55 years

For the first time in 55 years, Mr. and Mrs. Parrott stand on former POW

camp site in Shin-Minato-machi

After becoming a prisoner of the Japanese military during World War II, Cecil

Parrott (79), from Bellevue City in the United States, spent some two years

in Omuta at Fukuoka Camp #17. On the 25th, for the first time in 55 years,

he stood where the old camp was. Looking over the site which had completely

changed, Parrot remarked briefly as he thought over the past, "Good..."

Parrot came to Omuta accompanied by his wife, Ruby (79), and friend, Wes

Injerd, interpreter and amateur historian who lives in Dazaifu. After lunch

at the Mitsui Minato Club with a Japanese friend, Takehisa Kabashima (92),

and his family who live in Miike, they all visited the former camp site in

Shin-Minato-machi. What was once a tree-less area has now become a field

of weeds and bushes, nothing like what it was over a half century before.

Squinting his eyes and looking all around, Parrott's face showed his strong

emotions.

Parrott is a former US soldier who became a POW in the Philippines and survived

the "Bataan Death March." Most of his time was spent in Omuta, from 1943

till just after the end of the war. Parrott said that during this time he

worked in the Miike Coal Mine. Once a timber he was carrying dropped on his

foot and broke a bone, so he was sent to Fukuoka Camp #1.

Yet even from the Death March Parrott was treated kindly by the Japanese,

such as when a military cook helped to sustain his life. Then later while

at the Omuta Camp, while helping a Japanese carpenter construct a new barrack,

was able to communicate successfully and received friendly treatment. Even

when the war ended and he was to return to the US, one of the military staff

at the camp came to see Parrott off, weeping, sad to see him leave.

Being finally free to take a walk in the city at the end of the war, he was

invited to the house of a young Japanese lady who fed him a chicken dinner.

He was also given some "tea and cookies" by a man in his fifties, and had

many other friendly contacts with both soldiers and civilians alike. "That's

why I have no bad memories here. It was good that I came to Omuta," Parrott

remarked.

After returning to the US, however, Parrott suffered some 15 years from the

effects of the war, one of which was a fear of large groups of people. He

found work as an engineer at Boeing and, after retiring, began his own business.

In 1986 while on a tour of Japan, Parrott and his wife left the tour group

and came to Omuta Station. They soon returned, however, as they had no

acquaintances there nor an interpreter.

Injerd is doing volunteer research on the war and collecting information.

He has gathered testimonies of those who were at the Omuta POW camp such

as Lester Tenney who has brought a civil lawsuit against the Mitsui Mining

Company for its forced labor and who also visited Omuta in December of last

year. Injerd is seeking those who worked as guards or anyone who can share

what it was like at that time at the POW camp.

Letter from Sen. Patty Murray to Cecil

Parrott:

UNITED STATES SENATE

October 30, 2000

Mr. Cecil Parrott

16245 Southeast 7th Street

Bellevue, Washington 98008-4915

Dear Mr. Parrott:

Thank you for your recent letter regarding the payment of reparations to

former World War II POWs. I appreciate hearing from you.

As you know, Senator Bingaman has introduced a bill, S.1806, which authorizes

the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to pay a gratuity of $20,000 to veterans

(or their surviving spouses) who served at Bataan or Corregidor in the

Philippines during World War II, and were captured and held as Prisoners

of War by Japan. Currently, this bill is pending in the Veterans' Affairs

Committee. As a member of the Veterans' Committee, I have worked to bring

this important legislation to the Senate floor for a vote.

As the daughter of a disabled American veteran, veterans' issues have always

been one of my highest priorities. It is no accident that I am the first

woman ever to serve on the Senate Veterans' Affairs Committee; I sought this

assignment to work on behalf of Washington's veterans. Rest assured, I will

certainly keep your thoughts in mind during any Senate consideration of these

important issues.

Again, thank you for writing me. I appreciate your input, and I encourage

you to keep in touch.

Sincerely,

(signed)

Patty Murray

United States Senator

Letter from Rep. Jennifer Dunn to Cecil Parrott:

UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

November 22, 2000

Mr. Cecil W. Parrott

16245 SE 7th St

Bellevue, WA 98008-4915

Dear Mr. Parrott:

Thank you for contacting me regarding U.S. prisoners of war (POWs) held by

Japan during World War II. I appreciate hearing from you and welcome the

opportunity to respond.

As you may know, legislation has been introduced in the U.S. House of

Representatives that seeks to compensate Americans who were forced to perform

slave labor by the Japanese during World War II. Representative John Mica

(R-FL) introduced H.R. 4438 which seeks to provide $4 per day plus interest

for each day that veterans, who survived the Bataan Death March, were held

as POWs by the Japanese. Additionally, Representative Dana Rohrabacher (R-CA)

introduced H.Res. 304 which expresses the sense of the House that Japan should

formally issue a clear and unambiguous apology for World War II war crimes

and seeks release of all records dealing with Japanese experiments on American

POWs.

Additionally, the Senate Judiciary Committee recently held a hearing on POW

survivors of the Bataan Death March in which several POWs described their

experiences. The POWs reported being shipped to Japan on ships whose lethal

conditions earned them the name "Hell Ships," and then of having to work

in mines, steel mills, and elsewhere for Japanese companies. I was deeply

touched and saddened by their descriptions of being starved, beaten by company

employees, and forced to do hard manual labor for Japanese companies.

I share your desire to seek reparations for U.S. POWs held by Japan during

World War II. As we continue to hold committee hearings and debate legislation

on this important issue here in Washington, D.C., rest assured that I will

keep your thoughtful comments in mind. Again, thank you for taking the time

to share your views with me. I look forward to hearing from you in the future.

Best regards,

(signed)

JENNIFER DUNN

Member of Congress

Lake Washington Veteran

The American ex-POW's and their Enemies

June 2001

The servicemen and women captured by the Japanese at the beginning of World

War II went through hell. Their captors did not know the meaning of the word

decency. The Japanese guards would beat or kill our people just on a whim.

This came to an end in 1945 when Japan surrendered to us "unconditionally".

In 1951, a formal peace treaty was signed in San Francisco by all nations

that participated in the Pacific war. Representing our government were the

desk warriors from our state department. Apparently the people who did the

fighting in the Pacific were excluded from this delegation. Since these

Washington warriors did not see combat they were apparently unaware that

Japan surrendered unconditionally. The treaty as signed could have been written

by the Japanese. Our delegation signed an agreement that granted the Japanese

government and their corporations amnesty for their wartime crimes. Many

of our ex-POW's lost their right to sue these organizations for our state

department to make such an agreement was either an act of stupidity or a

sellout to our business interests. (In those days we were using the Japanese

for cheap labor.)

In 1999, two ex-POW's filed suit against the Japanese in U.S. District Court

in San Francisco. They are asking compensation from these wealthy corporations

that used them as slave laborers. Providing testimony for the Japanese was

our very own state department. They told the judge if he ruled in favor of

the POW's it would be 'an act of bad faith'. As a result of the statement

from this government agency, the judge ruled against our POW's.

There are words to describe the State Department action in both 1951 and

1999 but the editor would never allow me to use them.

Two members of Congress are as outraged by these actions as we are. They

introduced house bill H.R. 1198. If passed, the bill will state the Japanese

are obligated to honor all claims of the 48 nations who signed the peace

treaty. Apparently six nations that did not have our state department as

their representative received much more favorable peace terms. As of this

writing, the bill has 45 co-sponsors. It has both Democratic and Republican

support. We have contacted both Jennifer Dunn and Jay Inslee and asked them

to be cosponsors.

There is something wrong with this picture. The United States carried the

biggest burden in the war against Japan. We did most of the fighting. We

had the most casualties. We forced the Japanese to surrender to us

unconditionally, yet six nations have a more forceful peace treaty than we

do. Of course, they may not have been represented by desk warriors.

Our Post is honored to have two members who participated in the Bataan Death

March, Cecil Parrott and O. A. Greer.

They are two of the finest human beings you will ever meet. They have, for

years, worked helping the poor and needy Veterans. The State Department owes

them, and other survivors of these death camps, an apology. There is a place

for desk warriors, but dictating the terms of the peace treaty is not one

of them.

John Kenny Public

Affairs Officer

Bellevue vet refused to die

in POW ordeal

Now war against terrorism

delaying his hope of justice

By Mark D. Baker

Journal Reporter, Eastside Journal

September 30, 2001

BELLEVUE -- This is a story of survival, of heroism and triumph and a final

quest for justice.

This is Cecil Waldo Parrott's story, the story of a man who survived as other

men dropped dead around him -- during the Bataan Death March, in the darkness

and desperation of the Zero Ward, as a slave laborer far below ground in

Imperial Japan's coal mines.

Maybe it was the friendly Japanese soldier he met along the way or the daydreams

of a future love that kept him going. Maybe it was the poetry he wrote, reminding

him of better days to come, or the myriad recipes he jotted down on the back

of canned food labels -- recipes concocted after the coal mines had blackened

his skin, but not his heart.

There may be days in a man's life when he thinks it might be better to be

dead than to witness the horror all around him.

Cecil Parrott has lived through such days.

One thousand, two hundred and twenty-eight days.

For more than three years during World War II, Parrott was imprisoned by

the Japanese -- from the time of the 55-mile death march on Bataan in April

1942 until the end of the war in August 1945.

During the eight-day forced march in the Philippines, he lost 66 pounds.

When he finally made it to Camp O'Donnell, a POW camp on Bataan, he carried

just 97 pounds of skin and bone on his 5-foot-8-inch frame.

Shipped to Japan in September 1944, Parrott spent a year working day and

night in the coal mines of the southern Japanese cities of Omuta and Fukuoka.

He is one of an estimated 5,000 to 6,000 men still living who worked there

-- for nothing. Not a dime.

It was war.

As they die off, men who were imprisoned by the Japanese during World War

II, those who suffered unspeakable horrors during the death march, in the

POW camps and coal mines, are going to their graves feeling slighted, says

Parrott, now 81.

While many Americans have embraced a new kind of war in response to the terrorist

attacks of Sept. 11, some veterans from an old war are still fighting.

"I went to Boise, the county seat, and signed up for the Army. And the

reason I chose the Philippines was because my older brother used to pal around

with a guy who was in the service before that. And he'd been in the Philippines.

And he talked as if it was a glorious place to be." -- Cecil W. Parrot

on his decision to join the Army in November 1940, a year before the Japanese

bombed Pearl Harbor

Vet not bitter, seeks redress

This month is the 50th anniversary of the formal peace treaty signed in San

Francisco between the United States and Japan. According to Japan and the

U.S. State Department, one provision of the treaty banned claims by Americans

used as slave laborers.

Parrott and the men who served alongside him have been fighting to get

compensation for the horrors they lived through. Bills in Congress seek to

pay the men, but now any action has been pushed back by the focus on the

terrorist attacks.

Parrott is also part of a class-action lawsuit filed in California in 1999

and now headed for the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals seeking damages

against present-day Japanese corporate behemoths Mitsui and Mitsubishi, owners

of the mining companies Parrott and about 20,000 other POWs worked for during

the war.

Ex-POWs such as Parrott want what they say is their fair share. In the other

major theater of World War II, a $5 billion settlement last year was divided

between nearly a million survivors who had worked as slave laborers for German

companies during the war.

A Bellevue resident since 1956, Cecil Parrott is a gentle soul. He is thoughtful

and reflective, and he does not seem bitter about his experience. He's not

some old war bird seeking revenge.

He doesn't talk much about the war, unless you ask. Then, from behind

bespectacled clear blue eyes, he tells you plenty.

"I think it's due to us, I really do," Parrott says. "We worked as slaves

for the Japanese. I don't know how much money they made back in that time,

but they made money off of us."

"If you had a ring that was so tight on your finger, because your finger

had swelled up some, they would cut your finger off. That's how cruel they

were." -- Parrott, on the treatment of Americans by Japanese soldiers

during the Bataan Death March

Born in Mount Vernon, in the Skagit Valley, on July 20, 1920, Parrott spent

his boyhood moving from town to town in Idaho, following a father who looked

for work as a carpenter during the Great Depression.

Before joining the Army in 1940, Parrott met a girl named Ruby at a vocational

school in Weiser, Idaho. They married in 1947; after the war, and 54 years

later they are still married and living in the Lake Hills area.

Unable to have children of their own, the couple adopted identical twin girls

in 1955, Mary Ann and Cheryl Lee.

But before all the good years of home and family, Parrott went through hell.

In November 1940, he found himself in the tropical wonderland of the Philippines.

It would be more than a year before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and

for Parrott, a private first class in the Army Signal Corps, the future was

bright and the nights were warm.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor changed all of that. America was at war,

and in early April 1942 the Japanese captured Bataan on Manila Bay.

Parrott and 70,000 other American and Filipino soldiers found themselves

walking 55 miles from the tip of the Bataan Peninsula inland to Camp O'Donnell.

Still in uniform, a young Cecil Parrott grins after his return from captivity

following Japan's surrender.

Starved and mistreated, kicked, beaten and stabbed along the way, only 54,000

made it to the camp. Almost 10,000 died; the rest escaped into the jungle.

Parrott believes that if not for one compassionate Japanese soldier who he

and five other marchers encountered along the way, he would not have made

it.

After five or six days of marching, they had fallen off from the main pack,

Parrott says. Up ahead, the soldier waved in a friendly, come-here way.

"By the time he waved at us, I was on my last legs and I couldn't keep up,"

Parrott said.

The Japanese soldier said in English: "You, come here, come here," Parrott

recalls. The men walked over, their legs buckling underneath them.

"You hungry?" the Japanese soldier asked. His own troops off on maneuvers,

the soldier offered the men some leftover food -- one mackerel, cut into

five pieces, some rice and some sweet tea. He told the men he that he had

been brought in as part of Japanese reinforcements. He said he had no hatred

toward Americans.

"I probably weighed about 80 pounds. When I was down there, somebody would

be dead next to me every morning I woke up. I decided I wasn't going to die

like the rest of them. There was no way I was going to go to Boot Hill."

-- Parrott, recalling Zero Ward at a POW camp in Cabanatuan City

At Camp O'Donnell, the POWs were slowly starving to death. The men ate whatever

they could find. If a stray dog or cat came into the camp, the men would

catch the animal if they could and skin it, cook it and eat it.

Parrott even ate cobra meat one time when a Japanese guard stabbed the snake,

yanked its fangs out and barbecued it for the POWs.

The regular diet consisted of a watery rice stew for lunch and rice with

maggots and vegetable tops for dinner.

Parrott was later moved to another POW camp, Camp No. 1 in Cabanatuan City.

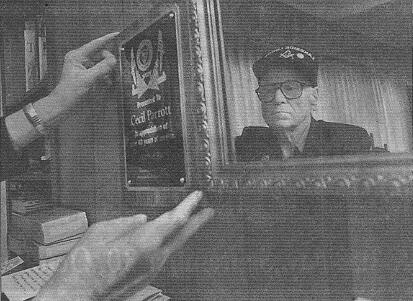

A plaque on the wall attests to Cecil Parrott's long involvement in a local

organization of former prisoners of war.

There, Parrott came down with dysentery and beriberi. One day, he was hauled

to Zero Ward, an area under the camp's barracks that held other men too sick

to function.

They were given no food and no water -- just left to quietly stop breathing.

"I was put down there to die," Parrott says. "I had no treatment of any kind."

It was a dreadful pit of a place filled with emaciated bodies and broken

spirits. Parrott saw that the men there had lost their will to live. They

talked about how their families had abandoned them, how they did not receive

any mail from them. But Parrott knew none of the men got mail -- the Japanese

didn't allow it. Parrott also knew the Zero Ward inmates were losing touch

with reality as their bodies withered.

Parrott, however, refused to die. He was too young to die, he told himself;

he had too much to live for. He did not want to be buried at Boot Hill; the

makeshift cemetery at the camp where each grave held 15 to 20 bodies. After

10 days in Zero Ward, the Japanese guards gave up on his dying and took him

back up out of the death chamber.

He credits his desire to live, his desire to one day eat rich, healthy meals,

to drive a new car, to fall in love, to hug family and friends, for keeping

him alive.

Back home in Idaho, Parrott's parents, John and Clara, had no idea what had

happened to him after Japan captured Bataan. They received a telegram saying

their son was among the dead and missing, along with another young soldier

from Weiser. It was not until 1943, a year after the march, that the couple

received word their son was a POW.

Later, Parrot was allowed to send a 45-word telegram to his mother: "Please

know that I am well. Am informing everyone of my health. Hope that brothers

and sisters are in good health. Give regards to all friends. Pass my love

to all relatives. Divine love to you and Dad. Four son, Cecil W. Parrot."

Although he wasn't the only POW to emerge alive from the Philippines, Parrott's

survival is nothing short of a miracle, say those who know of the horrors.

POWs came home with stories of being beaten and tortured and witnessing public

executions in which their comrades were blindfolded and decapitated.

"Camp O'Donnell was, for many, the most horrific experience of the war,"

writes Hampton Sides in his current best-selling book, "Ghost Soldiers,"

published this year.

"It was the place where all the seeds of hunger and disease sown on Bataan

came to full fruition. Americans had not seen derivational grotesqueries

on such a vast scale since the days of Andersonville, the infamous Civil

War death camp for Union soldiers in Georgia. One prisoner later wrote, 'Hell

is only a state of mind: O'Donnell was a place.'"

Twenty-seven percent of Japanese captives died during the war, compared to

4 percent of Allied POWs held in German and Italian camps, according to Sides'

book.

In September 1944, Parrott was put on one of the infamous Hell Ships, so

named because of their horrendous living conditions, and taken to Japan.

"That was one of the worst beatings I ever got. In fact, we called him

The Maniac because he was a known killer. He beat one guy, actually broke

his back with a 2 by 4." -- Parrott, describing a Japanese guard who

beat him after a day in the coal mines

At Camp 17 in Omuta, Parrott and other POWs mined coal for Mitsui Mining.

Later he was taken to another city, Fukuoka, for more dangerous and exhausting

work. One day a large timber fell on his ankle, nearly mangling it. He walked

club-footed for awhile, but the ankle eventually healed itself.

On another day, he was bloodied by a Japanese guard. The man accused Parrott

-- who then weighed all of 125 pounds -- of not saluting him, and he beat

Parrott to a pulp.

After three years of being around Japanese soldiers and guards, Parrott learned

to speak the language and is still fluent today. Prisoners had to learn to

count in Japanese because the guards would call out their numbers and if

they didn't respond they were beaten over the head with a stick.

At night, he and other POWs wrote poetry and recipes -- filled with eggs

and butter and "nothin' but good stuff" -- on the backs of canned-food labels.

Anything to keep them going.

On Aug. 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, killing

about 135,000 civilians. On Aug. 9, another bomb hit Nagasaki, killing about

70,000. Japan surrendered a few days later, and the war was over.

But Parrott and other POWs in Fukuoka, situated between Hiroshima and Nagasaki

in southern Japan, did not know it.

They were told American planes were in the area on reconnaissance missions,

not to drop bombs. It wasn't until Aug. 19, four days after Japan surrendered,

that American troops showed up to release and feed the POWs.

By September, Parrott was home, checking in and out of Fort Lewis, receiving

hugs from family and friend.

But he never got to see his father again. John Henry Parrott, 63, died in

a Wieser hospital from a lengthy illness shortly before his son's rescue.

"I know back in 1951, when they met in San Francisco, they had no idea

how we were treated. I think it was stupid of the State Department, at that

time, to make the decision that they did against us, without even knowing

anything about it." -- Parrott, on the peace treaty that barred any

claims by Americans

Government defends 50-year-old treaty denying former POWs right to reparations

For years after the war, Parrott went on with his life, trying to bury the

memories and the horrors he lived through. After graduating from Oregon State

University in 1952, he worked 18 years as a Boeing engineer.

Then one day a couple of years ago, he got a call from Lester Tenney, a former

POW and retired Arizona State University history professor, who was suing

Mitsui and Mitsubishi. Suddenly Parrott was part of a class action lawsuit.

And he got to thinking.

"Our government stood behind the guys that were fighting Germany, and they

allowed their claim to go through. I don't understand why they don't let

our claim go through," Parrot says.

Regardless of what the peace treaty between the two countries says, Parrott

contends he and his fellow POWs are getting a raw deal.

In recent years, the State Department has testified in cases against Mitsui

and Mitsubishi, saying terms of the peace treaty with Japan should be upheld.

Parrott has no ill feelings toward the Japanese; much of the reason is the

friendly soldier who may have saved his life during the death march.

In 1981, he returned to Japan for the first time and tried to find the camps

where he had lived, but they were gone. Only a smokestack remained at one.

He returned again last year to Japan and stayed with the parents of a Japanese

woman he met a few years ago at Newport Hills Community Church. Coincidentally,

the woman's grandfather, an engineer, designed part of a coal mine where

Parrott labored during the war.

But such friendships don't change his feelings about the war, and Parrott

said he wants justice before he dies.

"I really think the American people should not forget what these brave men

went through."

Mark Baker can be reached at mark.baker@eastsidejournal.com or

425-453-4248.

Terrorist attacks divert attention

from POW bills

By Mark D. Baker

Journal Reporter

September 30, 2001

Fifty-six years after World War II ended, Congress was ready a couple weeks

ago to send President George W. Bush a bill that could help the men who toiled

in Japan's coal mines.

But now, lawmaker's are focused on responding to the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks;

leaving many congressional bills for another day.

The U.S. Senate approved an amendment Sept. 10 that would bar the Justice

and State departments from spending funds to oppose slave-labor lawsuits

brought by former prisoners of war against the Japanese businessesthat once

enslaved them. The House approved a similar measure in July.

"Anything that is divisive has pretty much been booted to next year," said

Gary Burns, an aide to Rep. John Mica of Florida. Mica authored the Samuel

B. Moody Bataan Death March Compensation Act.

That bill, and one in the Senate, seek to pay the former POWs for the traumas

they suffered.

But it is the amendments that would restrict how the State and Justice

departments operate in court that could have the biggest effect.

Several California lawsuits also seek reparations for the men who worked

in the coal mines.

A class-action lawsuit that includes Cecil Parrott, a Bellevue resident

and ex-POW, was dismissed last year in federal court in San Francisco. The

case has been appealed to the 9th Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals, said

David Casey Jr., a San Diego attorney representing Parrott and thousands

of other men.

U.S. standing by treaty

The case, along with several others, hasfailed so far largely because the

U.S. State Department acted as a witness for Mitsui Corp. and Mitsubishi,

the companies that owned the coal mines the men worked in, Casey said.

The State and Justice departments have testified in several cases brought

before California courts, saying the 1951 peace treaty between the United

States and Japan should be upheld. The treaty bars any claims against Japan

for wartime atrocities, a State Department official said.

The State Department is "strongly opposed" to Congressional action, the official

said. The U.S. government interprets the treaty as "waiving all claims,"

he said.

"So it is the position of the executive branch and the present administration

that the treaty should be upheld," he said.

"The situation with Japan was different from the situation with the Germans

in that there was no comprehensive treaty with Germany that included anything

regarding claims."

About 1 million wartime survivors who performed slave labor for Nazi-backed

companies during World War II, along with their descendants, split a $5 billion

settlement last year.

Washington Sen. Patty Murray and Rep. Jennifer Dunn, R-Bellevue, are backing

Parrott's fight.

"She believes that our veterans shouldbe able to have their fair day in court,"

said Todd Webster, Murray's press secretary. "Until this time, the State

and Justice departments have been preventing that."

Murray's father, Dave Johns, was a disabled World War II veteran who died

about a decade ago from complications related to multiple sclerosis, Webster

added.

Payment proposals differ

Besides the recent amendment concerning lawsuits, there is also a bill pending

in the Senate to pay veterans who were captured and held as POWs by Japan,

or their surviving spouses, $20,000.

Mica's bill, introduced last year, would pay them $4 a day for each day spent

in captivity, plus interest compounded at a rate of 3 percent a year.

Samuel Moody, the man the bill is named for, was a resident in Mica's east

central Florida district and was part of the death march. He wrote a book

about his experience, "Reprieve from Hell," and his story touched Mica, Burns

said. Moody died in 1999.

The Congressional Budget Office prepared a cost estimate of the bill in April.

It found there are about 4,500 remaining veterans of the death march. On

average, each veteran spent about 3 years in captivity, as Parrott

did, which would make the payments about $27,000 each under the bill.

In addition to House Bill 963, House Bill 304 has been introduced by Rep.

Dana Rohrabacher and would simply ask Japan to issue a formal apology for

World War II crimes and to release all records dealing with Japanese experiments

on American POWs.

"If we don't do something soon, we won't have a problem anymore because they'll

all be gone," Burns said of the ex-POWs.

The lawsuits in California fall under a 1999 state law there, that allows

victims of slave labor to sue multinational corporations in state courts.

The first lawsuit was brought by former POW Lester Tenney, a retired

Arizona State University professor and a San Diego resident.

Cecil Parrott, Death March survivor, dies

2004-04-18

by Lori Varosh

King County Journal Reporter

He survived the infamous Bataan Death March, and endured savage beatings,

bouts of dysentery and starvation as a Japanese POW in World War II.

But Cecil Waldo Parrott lost his final battle.

The Bellevue resident did not live to win reparations for himself and thousands

of other POWs forced to work without compensation for Japanese companies.

Parrott died Thursday at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Seattle.

He was 83.

Though he endured 1,228 days in captivity, as one of 70,000 U.S. and Filipino

soldiers who surrendered to the Japanese on April 9, 1942, Parrott maintained

his faith in family and refused to hate his captors.

He was a gentle man who "loved the Japanese people,'' said his son-in-law

David Andress of North Bend. "He was very forgiving of the Japanese people,

because he knew it wasn't the people (who caused the suffering), it was the

military.''

Born in Mount Vernon on July 20, 1920, Parrott spent his boyhood moving from

town to town in Idaho as his carpenter father sought work during the Great

Depression.

He met his future wife, Ruby, at a vocational school in Weiser, Idaho. They

would marry in 1947, after the war ended.

Parrott enlisted in 1940, and spent more than a year stationed in the Philippines

before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. He was a corporal in the U.S. Army

Signal Corps when the Japanese captured the Bataan peninsula.

More than 10,000 soldiers would not survive the resulting Death March, victims

of exhaustion, thirst, disease and horrific treatment by their captors.

"If you had a ring that was so tight on your finger, because your finger

had swelled up some, they would cut your finger off. That's how cruel they

were,'' Parrott told the Journal in an interview in 2001.

"I saw men bayoneted for trying to get a drink. I decided that dying of thirst

was preferable,'' he said.

He credits a cook from the Japanese army with helping him survive and enabling

him to see the enemy as individuals.

He and other stragglers were stopped by the cook, who shared what little

he had ----some boiled rice, sweet tea and one mackerel, cut into five pieces.

The tea, the only clean water he had during the march, probably saved his

life, Parrott told the Journal.

Surviving the nearly 70-mile march was no guarantee of surviving the war.

By late 1942, in Camp O'Donnell in Luzon, dysentery, beriberi and starvation

had carved 68 pounds from his 165-pound frame. He was sent to "Zero Ward,''

a crawl space under the barracks where men were left to die.

Every morning, Parrott would wake up with yet another dead man next to him.

"I noticed that the night before a guy died, he would talk about how abandoned

he felt, how he was convinced no one cared, that his family had forgotten

him,'' Parrott told the Journal in May 1995. "Not me. I would get home to

my family.''

Parrott simply refused to give up. He weighed 96 pounds when he was liberated

from a Japanese work camp on Aug. 19, 1945.

Parrott moved to Bellevue in 1955 and worked as an engineer for Boeing until

the layoffs of the early 1970s, son-in-law Andress said. Then he opened his

own general contracting business before retiring a decade ago.

He was known for helping veterans and for putting in grab-bars for seniors

for a minimal charge, just to help out, Andress said.

"He was a giving person,'' Andress said.

The war brought Parrott a Purple Heart, Bronze Star and other medals, but

left him with nightmares and digestive problems throughout his life, Andress

said.

He testified against some of the prison guards after the war, "but he was

able to separate individual Japanese people,'' Andress said.

"We should never forget the sacrifices Americans have made in war,'' Parrott

told the Journal in 1995. "But we also should remember the point of it all:

peace and brotherhood among all peoples.''

In 1999, Parrott joined a class-action lawsuit filed in California seeking

damages against present-day Japanese corporations Mitsui and Mitsubishi,

owners of the mining companies that used the labor of 20,000 POWs during

the war. They have not been compensated to this day.

"What's sad,'' Andress said, "is at the end he was very upset'' about that.

Parrott is survived by his wife of 56 years, Ruby of Bellevue; daughters

Cheryl (and David) Andress of North Bend and Marcy (and Tim) Davis of Yakima;

and five grandchildren.

Services have not yet been scheduled.

-- Posted by permission --

Back to Main Page Index

|