Description

of

Fukuoka POW Camp

17 (Omuta)

Description of the camp, as taken from reports from interned American prisoners of war (Liaison and Research Branch, American Prisoner of War Information Bureau, 31 July 1946; Author: John M. Gibbs).

Notes in blue were

provided

by Louis "Goldy" Goldbrum, former Camp 17 POW #45. Comments

and notes on camp descriptions in green type are provided by Ortwin

Louwerens, former Camp 17 POW. My notes are initialed "LD."

LOCATION:

Omuta, on a bay, about 17 miles northwest of Kumamoto and 40 miles south of the city of Fukuoka, opened on 7 August 1943. The coordinates are 33.000N, 130.420E. Terrain level, well-drained and filled in with slag from a coal mine at Omuta.DIMENSIONS AND PARTICULARS:

The original camp site was 200 yards square. By April 1945, the size had been increased to 200 yards x 1000 yards. The site is a reclaimed grove and the buildings thereon were formerly laborers' quarter constructed by Mitsui (Baron Mitsui) Coal Mining Company and operated by the Japanese Army. A wood fence, approximately 12' high with three heavy gauge wires (first wire approximately 6 feet off the ground), enclosed the compound. The grounds were kept as clean as possible at all times. Some fir trees adorned the compound. The Japanese officials were stationed in the enclosure.PRISONER PERSONNEL:

- Major John R. Mamerow, later sent to Manchuria

- Captain

Achille C. Tisdelle, former aide to General

King (See these news articles.)

- US Navy Edward N. Little, mess officer, later court-martialed for cruelty to Americans

- Captain

Thomas H. Hewlett, camp surgeon

- Lieutenant Harold Proff, medical officer

- Australian Camp Commandant, Lt. Reginald Howel

- Australian Camp Physician, Captain Ian Duncan

LD: The letter

below

is from Camp 17 POW Ortwin Louwerens. Depending upon where the POW's

were housed in Camp 17, (British, Dutch,

Americans, etc. were in separate barracks and areas) some former POW's

concur with Louwerens, most others concur with Dr. Hewlett. I felt this

was an important point of view to include and share with the reader.

The summary is that each prisoner suffered "hell" under the appalling

and inhumane treatment by the Japanese. Differences in opinions

of various reports does not take away from the fact the prisoners all

were subject to atrocities that those of us "not

over there" could ever expect to understand or comprehend.

Dear Linda,

While reading your website on Fu.17 for more reports, I came on that Camp Medical Report by Dr. Hewitt and was completely overwhelmed by the facts that there were numerous wards as well as a surgery department (in the Camp?!!) and most of all that there also has been a Dutch doctor Bras.

I already told you in my comments and sketch of the camp that there only was a medical ward (one barrack) and a separated quarantine ward with some 9 beds (real beds) for Tuberculosis patients. I was there for several days because of my smallpox (the Japanese doctor considered this as very contagious).

Either I missed quite a lot during my 18 months in Fu.17, or I have been completely blind!! But Dr. Hewitt, who made the report,also reported several cases of OEDEMA in 1945. I only can tell you a story most probably related to this appearance of oedema.

The Japanese rice was always polished, of good quality,but unfortunately also too luxurious for POW's and therefore it was (for us) always mixed with soybeans, so called pigeon weed (small grains half white, half red) and potatoes. Soya and pigeon weed have Vitamins B and also the soy-paste in which the vegetables and seaweed were impregnated, not much but just enough.

Sometime at the beginning of 1945- end 1944 we received non-food articles from Red Cross parcel and amongst these also coffee-powder. But we also got a pack American cigarettes and you could swap one American cigarette for some SALT with the Koreans in the mine!! This salt was a delicacy with your meal in the camp but it also produced an hour or two later a swelling in your legs, and we knew that this swelling should not go further than the knees. So when it reached that level we dissolved some coffee-powder in hot tea-water and drank it. After several hours you had to piss continuously to drain the swelling in your legs. Maybe the reported case of oedema was someone who did not have anymore coffee-powder!!

Many cases of the reported pneumonia were also caused by washing yourself clean in the mine (down below there was plenty of water) before going up with the train and expose yourself during 10 to 15 minutes to the draught in the tunnel, only to have more time left in the warm waiting room to take a smoke. We were always warned not to do this.

While reading your website on Fu.17 for more reports, I came on that Camp Medical Report by Dr. Hewitt and was completely overwhelmed by the facts that there were numerous wards as well as a surgery department (in the Camp?!!) and most of all that there also has been a Dutch doctor Bras.

(Louwerens

was misinformed - there was a Dutch doctor; many references

are made of him. LD)

I already told you in my comments and sketch of the camp that there only was a medical ward (one barrack) and a separated quarantine ward with some 9 beds (real beds) for Tuberculosis patients. I was there for several days because of my smallpox (the Japanese doctor considered this as very contagious).

(We believe Louwerens is

describing the Dutch side and that is why he

felt the American descriptions were inaccurate. LD)

Either I missed quite a lot during my 18 months in Fu.17, or I have been completely blind!! But Dr. Hewitt, who made the report,also reported several cases of OEDEMA in 1945. I only can tell you a story most probably related to this appearance of oedema.

The Japanese rice was always polished, of good quality,but unfortunately also too luxurious for POW's and therefore it was (for us) always mixed with soybeans, so called pigeon weed (small grains half white, half red) and potatoes. Soya and pigeon weed have Vitamins B and also the soy-paste in which the vegetables and seaweed were impregnated, not much but just enough.

Sometime at the beginning of 1945- end 1944 we received non-food articles from Red Cross parcel and amongst these also coffee-powder. But we also got a pack American cigarettes and you could swap one American cigarette for some SALT with the Koreans in the mine!! This salt was a delicacy with your meal in the camp but it also produced an hour or two later a swelling in your legs, and we knew that this swelling should not go further than the knees. So when it reached that level we dissolved some coffee-powder in hot tea-water and drank it. After several hours you had to piss continuously to drain the swelling in your legs. Maybe the reported case of oedema was someone who did not have anymore coffee-powder!!

Many cases of the reported pneumonia were also caused by washing yourself clean in the mine (down below there was plenty of water) before going up with the train and expose yourself during 10 to 15 minutes to the draught in the tunnel, only to have more time left in the warm waiting room to take a smoke. We were always warned not to do this.

Ortwin

Camp interns included 10 officers, 133 NCOs and 358 privates, a total of 501, all Americans, from the Philippines. 497 American prisoners from the Philippines reached the port of Moji, Kyushu, on 29 January 1945 and were divided among the Fukuoka area installations as follows:

100 to Camp #3, located at Tobata

193 to Camp #1, located at Kashii

110 to the Japanese Military Hospital at Moji

95 to Camp #17

Only 34 of the hospital prisoners, later transferred to Camp #22, survived. The death of the 76 prisoners while in the hospital was due to the horrible conditions of travel from the Philippines to Moji and extreme malnutrition.

An earlier group of 200 American prisoners from the Philippines reached Moji on 3 September 1944, all of whom were assigned to Camp #17, making a total of 814 American prisoners, which was the maximum. The camp was liberated on 2 September 1945. There were 1721 prisoners in the camp toward the closing of it on 2 September 1945. British, Australian, Dutch and American prisoners evacuated the last minute from the Philippines and Siam were in desperate physical condition when they arrived.

GUARD PERSONNEL:

Asao Fukuhara, camp commandant.Unnamed Japanese officer, camp surgeon and civilian guards.

Several pseudo names were given by the POW's for the Japanese Guards:

Sailor, One-armed Bandit, Pig, Smiley, Long Beach, Riverside (the Japanese Interpreter), Yotojisa also called Flangeface, Fox, Screamer, Devil, Wolf, Sikimato San-called Blinkey, Mouse, Big Stoop, Gold teeth, Turtle, Devil, Toko-San also called Billy Goat, Rat, Greyhound, Wingy, Pretty Boy and The Bull.

(See the

Biographies for some of the

names recalled by POWs in their personal accounts. LD)

NOL: The guards were Japanese military personnel; Japanese civilians were the foremen (hanchou) and "overmen" in the mines and sink factory. The Japanese soldiers were young and fanatic and therefore not easy or friendly.

NOL: The guards were Japanese military personnel; Japanese civilians were the foremen (hanchou) and "overmen" in the mines and sink factory. The Japanese soldiers were young and fanatic and therefore not easy or friendly.

GENERAL CONDITIONS:

(a) housing facilities. The barrack comprised 33 one-story buildings, 120' x 16', with ten rooms to a barrack, of wood construction with tight tar paper roofs. More barracks were built a more prisoners arrived. Ventilation was satisfactory. Three to four officers were billeted in one room, 9' x 10'. No heating facilities, and while the climate was mild, it must be remembered that the men were sensitive to temperatures around 50 degrees F, and because of their weakened condition due to malnutrition, the dampness and cold were very penetrating. The barracks were light enough during the day without artificial illumination. Each room had one 15-watt light bulb.

Air raid shelters were dug into the earth about 6' deep and 8' wide, 120' in length, timbered in similar manner, to coal mines, covered with 3' of slag and an adequate splinter-proof roof.

OL:

During the bombardment in June 1945 two of

our barracks -- one of them was my housing -- were hit and burned down;

the

occupants of these two barracks had to sleep with one blanket on the

tables at the far end of the mess hall till the day we were evacuated!

Luckily the occupants of the two barracks worked in separated

mine-shifts.

The beds consisted of tissue paper and cotton batting covered with a cotton pad 5'8" long and 2' 6" wide. Three heavy cotton blankets were issued by the Japanese in addition to a comforter made of tissue paper, scrap rags and scrap cotton.

(b) latrines. In each of the 33 buildings, and at the end thereof, were three stools raised from the floor about 1.5 feet on a hollow brick pedestal, each being covered with a detachable wood seat, and one urinal. A concrete tank was underneath each stool. The prisoners made wood covers for each of the stools, thereby reducing the fly nuisance. The offal in the tanks were removed by the Japanese laborers each week.

OL: A Japanese farmer did the offal to use

it as dung in the fields, a common use in Japan where the offal was

gathered in pits in the field.)

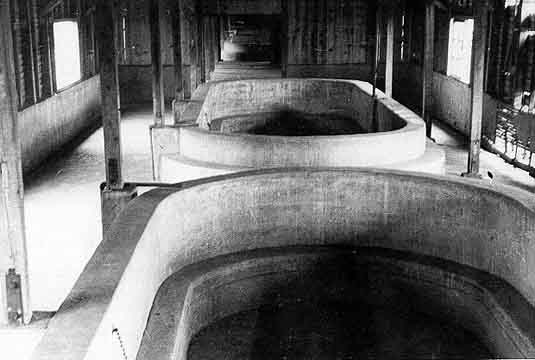

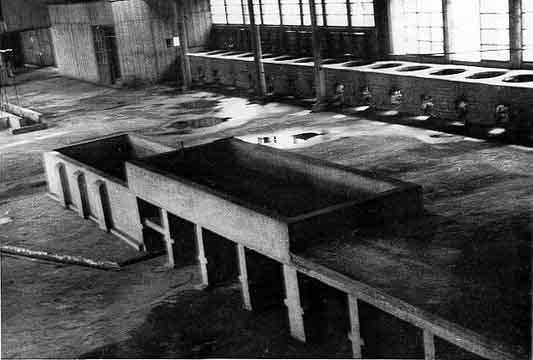

(c) bathing. The bathing facilities were in a separate building equipped with two tanks (shown above) approximately 30' x 10' x 4' deep, with very hot, steam-heated water. The American camp spokesman would not permit the men to immerse themselves during the summer months on account of skin disease. In the winter the tubs were used but not until the men had taken a preliminary bath before entering the tubs. The men were required to watch each other to see that none "passed out" because of the heat and their weakened condition. After bathing, the men would dress in all the clothing they had and go to bed for the night. Even then the prisoners would fill their canteens with hot water and place them beneath the covers. With these precautions, the men slept comfortably through the cold nights. Every two barracks had an outside wash rack, 16 cold water faucets and 16 wood tubs with drain boards. Prisoners washed their clothes by scrubbing with brushes on the drain board and rinsing them in the tubs. There was a constant shortage of soap.

OL: The

mineworkers had to take a bath in the mining-compound with two large

tanks with hot water, because you needed it to wash off the coal dust.

I think it was the same in the sink factory.

(d) mess hall. There was one unit mess with 11 cauldrons and 2 electric cooking ovens for baking bread, 2 kitchen ranges, 4 store rooms and 1 ice box. Cooking was done by 15 prisoners of war, 7 of whom were professional cooks, all working under the supervision of a Japanese mess sergeant. The men working in the coal mines were given 3 buns every second day to take with them for their lunch when they did not return to the camp to eat. Other days they were given an American mess-kit level with rice. Prisoners ate in the mess hall in which were placed tables and benches.

Goldy: The

mess was entirely ruled

by

Lieutenant Little. If supervised by a Japanese mess sergeant, it

was seldom evident. Little went as far as ingeniously

constructing scales to make sure the POWs did not get an extra grain of

rice. People working in the mine received only two meals a

day. Going to work, they received a box about the size of a

25-cigar box with steamed rice and topped off by several slices of

salted radishes and several strips of soy-soaked seaweed.

OL: There was plenty of hot tea in a huge wooden container in the mess hall, but it was tea from the stems only; tea leaves were not for POWs.

OL: There was plenty of hot tea in a huge wooden container in the mess hall, but it was tea from the stems only; tea leaves were not for POWs.

(e) food. Usually consisted of steamed rice and vegetable soup made from anything that could be obtained, three times a day. Upon occasion of a visit to this camp by a representative of the Red Cross in April 1944, a splendid variety of fats, cereals, fish and vegetables were served, which naturally impressed the representative, and in his report to headquarters he called particular attention to the menu. It is known that the spread was to impress the Red Cross man, and that it was the only decent meal served in two years. Rice and soup made with radishes, mostly water, remained the diet throughout. The men working in the mines were given 700 grams of rice, camp workers 450 and officers 300. Our American camp doctors stated that such scant ration was insufficient to support life in a bed patient. All of the prisoners were skeletons, having lost in weight an average of around 60 pounds per man. Again, only men in the mines were given buns to eat. The city water was drinkable.

Goldy: I do

not recall any vegetable soup or buns except on rare occasions. We

were given a roll or baked sweet potato when we came out of the mine at

the end of the work shift.

OL: I have never received any bun -- this was luxury -- as a meal for the mines, neither as one of the other meals, with the exception of 2 or 3 times we got baked bread (a third of a loaf as a complete meal). As for a meal, it normally was always rice with some pickled vegetables and/or seaweed and not more than a spoonful. I think the POW-personnel working as cooks did their utmost to make the best of it.

LD: Several POW's have mentioned buns, however several noted that the buns were allotted by the mess hall crew and receiving one was sometimes dependent upon who, at the time, the mess crew "favored."

OL: I have never received any bun -- this was luxury -- as a meal for the mines, neither as one of the other meals, with the exception of 2 or 3 times we got baked bread (a third of a loaf as a complete meal). As for a meal, it normally was always rice with some pickled vegetables and/or seaweed and not more than a spoonful. I think the POW-personnel working as cooks did their utmost to make the best of it.

LD: Several POW's have mentioned buns, however several noted that the buns were allotted by the mess hall crew and receiving one was sometimes dependent upon who, at the time, the mess crew "favored."

(f) medical facilities. Medical section and surgical section of the infirmary had ten rooms each with capacity for 30 men. Isolation ward could accommodate 15 men. Daily medical and dental inspections by American officers, but they had but little to work with in the way of medicines and instruments. The dentists had no instruments and could only perform extract ions, and without anesthesia. For dysentery, the Japanese provided a powder which they concocted, the use of which produced nausea and diarrhea when administered to the American patients. There were no American hospital corpsmen in this camp until April 1944, when 10 men were added to the hospital corps with two doctors and one dentist. After October 1944 medical supplies were provided and an operating room installed. Prior to October 1944 the camp was practically without medical supplies. The Japanese doctor was entirely disinterested.

OL: The only doctor I have seen during my

18 months was the Japanese doctor and American orderlies -- mostly Navy

personnel -- who did an excellent job under these circumstances. I

myself

was treated because of ulcers because of lack of vitamins -- two times

by

incision with a razorblade with no painkillers and another time because

of a kind of tropical open wound, neglected and looked very bad and

like green moss growing on it, but the orderly managed to clean the

whole wound with pincers up to the fresh meat and powdered it with

silver-nitrate of which he (the orderly) still had something left.

(g) supplies (1) Red Cross, YMCA, other: The first Red Cross and YMCA supplies were received early in 1944 on the Japanese ship Teia Maru. The items in the food parcels were doled out to the men sparingly provided he had a consistent work record in the coal mine and was not guilty of infractions of rules. In the aggregate each man was given the equivalent of about one complete parcel during the full period of the confinement. The favoritism shown the mine workers in the distribution of parcel items defeated the intention of the Red Cross because it tended to give protein foods to the more healthy rather than to the weak. The 1944 Red Cross shipment contained medicines, surgical instruments and other supplies which the Japanese refused to make available for the benefit of the invalid men, but helped themselves to them. The YMCA furnished several hundred books. (2) Japanese issue: The clothing (cotton) was issued by the coal mine company and was adequate. British overcoats were given out by the Japanese army. Each prisoner was given three heavy cotton blankets and a comforter made of tissue paper and scrap rags and scrap cotton. The canteen was practically bare. From it the men received regularly five cigarettes per day. Canned salmon could be bought about every two months, one can per man.

Goldy: I do

not recall canned

salmon,

but I recall a round container containing dry fish powder, which we

used as a condiment over our rice. At one time there was a

beached whale, and we got left-overs.The whales was spoiled and

some chose not to eat any. They were the fortunate men, as the whale

made most of them very sick. The Red Cross parcel was a joke and not

even worth mentioning.

OL: Rationing of cigarettes was based on one cigarette for one working-day; that is one pack of 10 cigarettes for one ten-days shift; I never have seen the mentioned can of salmon. Because of the scarceness of cigarettes they were priceless; two cigarettes for a half bowl of rice, or one and a half cigarette for the soup was a common daily deal in the mess hall. During my time I received one Red Cross parcel, that is to say that we only received the non-food articles; the cans of food were stored by the Japanese and occasionally we saw or tasted some in our soup and the market-value in cigarettes was accordingly double or triple! Unfortunately this storage-room (like my barrack) was also hit and burned down when our camp was hit during a bombardment.

OL: Rationing of cigarettes was based on one cigarette for one working-day; that is one pack of 10 cigarettes for one ten-days shift; I never have seen the mentioned can of salmon. Because of the scarceness of cigarettes they were priceless; two cigarettes for a half bowl of rice, or one and a half cigarette for the soup was a common daily deal in the mess hall. During my time I received one Red Cross parcel, that is to say that we only received the non-food articles; the cans of food were stored by the Japanese and occasionally we saw or tasted some in our soup and the market-value in cigarettes was accordingly double or triple! Unfortunately this storage-room (like my barrack) was also hit and burned down when our camp was hit during a bombardment.

(h) mail. (1) incoming: First incoming mail was received in March 1944, thereafter each 60 days. Some received mail, some received none at all. It as all at the "whim" of the Japanese. However, if there was bad news, the Japanese most always made sure a POW received that mail.

(2) outgoing: Prisoners were allowed to write a card about every six to eight weeks. Very few made them "home."

(i) work. In coal mines and zinc smelters three shifts per day of approximately 100 men per shift. Conditions in the mines were pronounced dangerous although only three men were killed outright during the period of confinement of 22 months. Many men received painful injuries from falling rock and other causes. Fortunately for the prisoner there was among the group an experienced coal miner who gave the men safety talks and pointed out some of the dangers of coal mining, which were not apparent to the novice miners. The coal mines were operated largely by American prisoners, the smelters by the British and Australian prisoners. Coal mines were approximately 1 kilometer from camp. Hours of work: 12 hours per day, 30 minutes lunchtime. The men were given one day off every 10 days.

Goldy: My

left hand was crushed in a

mine cave-in and thanks to the expertise of Dr. Hewlett, it was able to

be repaired when I returned to the US and entered a VA hospital.

OL: In the mine we were divided in working-shifts of about 15-20 men to work in one coal-galley supervised by a civilian hanchou who told you with arms and legs what you had to do and then find out for yourself. There were no instructors or something of the kind. The shifts were a 10-day shift and depending on the changing of the shifts you had a day (off) in between and that only occurred once in a month. Because of roll-calls and endless counting procedures in the camp and on the mining compound you were about 12 hours ¨busy.¨ You had quite a rotten day when there also was one of the regular inspections on the camping ground. Work in the mines was done mostly by POW-s and also Korean contract-workers; unpleasant people.

OL: In the mine we were divided in working-shifts of about 15-20 men to work in one coal-galley supervised by a civilian hanchou who told you with arms and legs what you had to do and then find out for yourself. There were no instructors or something of the kind. The shifts were a 10-day shift and depending on the changing of the shifts you had a day (off) in between and that only occurred once in a month. Because of roll-calls and endless counting procedures in the camp and on the mining compound you were about 12 hours ¨busy.¨ You had quite a rotten day when there also was one of the regular inspections on the camping ground. Work in the mines was done mostly by POW-s and also Korean contract-workers; unpleasant people.

(k) treatment. Often the men were beaten without cause with fists, clubs and sandals. Failure to salute or bow to the Japanese was an offense which usually was followed by compelling the prisoners to stand at attention in front of the guard house for hours at a time. Some men were beaten daily and other harassed by guards while trying to sleep during their rest time.

OL:

The worst cases I saw were an American NCO Johnsen

or Jones (something like that) who got a beating in front of the

guardhouse with a rod or something of the kind, because he wore his US

Army cap. The beating (we saw it from our barrack) was so bad that he

died the next day. In another case an Australian who took a nap in the

coal mine and fell asleep, without warning his other companions; so at

the roll call outside he was missing. After we were back in the camp

again he had woken up and reported to the guards of the other shift.

The Japs considered this as an effort to escape and was punished by

kneeling in front of the guardhouse with a bamboo stick between his

knees and calves on his legs during the whole night in wintertime. The

result was quite evident: both legs to the knees amputated. But he

survived anyway.

(l) pay. (1) Officers: were paid 20 yen per month until June 1944, when it was increased to 40 yen less 18 yen per month for mess. Each prisoner received 5 cigarettes per day regularly except for about one day per month. Postal savings accounts for officers were deposited with Protecting Power amounted to 7,688.26 yen. Prisoner of War headquarters ran its own destitute welfare. (2) Enlisted men: NCOs were paid 14 sen per day and privates 10 sen per day. No postal savings were deposited with Protecting Power.

OL: The payment

was very unimportant to us as long as we received our cigarettes each

10 days a package of 10 and toothpowder and some soap.

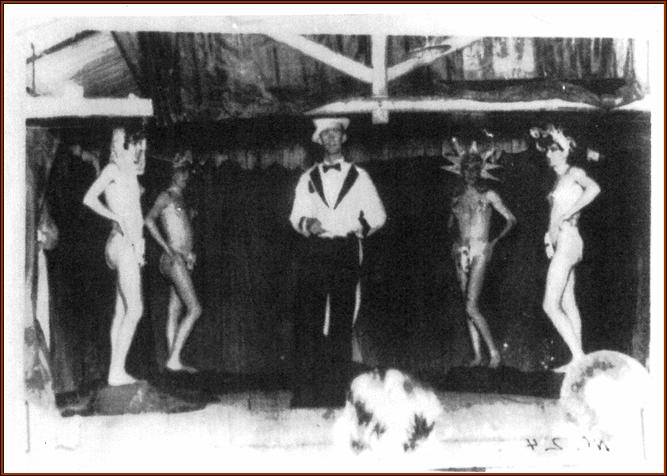

Lester Tenney Tennenberg wrote- "I was asked by Major Mamerow to be in charge of the little entertainment we could have, and 'The GREAT ZIGFIELD' was the culmination of my effort... a musical comedy was the result. The Japanese allowed this show, and Baron Mitsui (Mitsue, Baron Mitsui, Coal Mining Company) came for the opening night." (August or September 1944)

(m) recreation. The YMCA provided equipment for such outdoor games as football, volleyball and tennis, but the prisoners, at the close of work periods, were too tired and weak to play. There were no indoor sports except those made by the prisoners. There was a rotating library of about 300 volumes provided by the YMCA

A vegetable garden was planted and maintained by the prisoners, and some live stock was raised, but the Japanese ate the live stock and none of it was made available

to the prisoners. Entertainment was allowed, tho rare. Often it was for the entertainment of the Japanese rather than the "concession" of such by the Japanese.

(n) religious activities. In July 1944 a Protestant Dutch Army chaplain arrived as one of a prisoner detail. Until his arrival the camp was without a chaplain. From July 1944 Protestant services were held each Sunday.

(o) morale. Was low because of inadequate food, long and hard working hours which left no time except for work and sleep. There was no laughter, no singing, nothing but depression which condition was made worse by beatings and the harassing activities of the Japanese guards during the sleeping hours.

MOVEMENT AND HELLSHIP ARRIVALS:

Of the original group of 501 officers and enlisted men who reached this camp in August 1943, at least 15 died. The remainder left for Mukden, Manchuria on 25 April 1945. Other American prisoners, approximately 340, remained at Camp #17 until liberated on 2 September 1945. Dutch, British and Australian POW's were to be interned, along with Norwegian and Czechoslovakian civilians.HELLSHIPS ARRIVALS IN OMUTA:

(Info courtesy of Jim Erickson)The first 500 POWs arrived at Camp #17 on 10 Aug 1943 after a 15 day journey from Manila to Moji aboard the Clyde Maru (known to the men as the Mate Mate Maru).

The next 7 Americans (#506-507) arrived on 24 March 1944 after a journey aboard the Kenwa Maru.

The third group to arrive was a mix of Australian (#507-655), British (#657-664), and Dutch (#668-928) POWs who arrived on 18 June 1944 after sailing on the Teia Maru. (ex Aramis).

The fourth group consisted of 200 British enlisted men and 2 officers (#931-1128) aboard the Hioki Maru.

The second large contingent of American POWs (#1131-1332) arrived on 2 Sept 1944 aboard the SS Canadian Inventor (the Mati Mati Maru).

The next group (#1337-1430) consisted of Dutch personnel transferred from other camps in Japan.

The seventh group were Australians (#1431-1629) who arrived 16 Jan 1945 after a journey aboard the Awa Maru.

A small group of Americans, Australians, British, and Dutch were transported from other Japanese Camps to Fukuoka #17 near the end of Jan 45. (#1632-1683)

On 30 Jan 1945 96 men from the Brazil Maru, including Capt. John Duffy went to Camp #17. Chaplain Duffy was moved to Mukden in April 1945. The other 95 men were assigned numbers 1684 to 1777.

A group of men from Taiwan make up the next group (#'s 1778-1873). The men most likely arrived in mid Jan 1945 aboard the Melbourne Maru, but may have come aboard Enoshima Maru in early Feb 1945. These men included British and Dutch survivors of the hellship Hofuku Maru, sunk off Luzon, 21 Sept 1944 with the loss of about 950 POWs. Many of these men were taken to Taiwan aboard Hokusen Maru in Oct-Nov 1944 and others on Oryoku Maru and Brazil Maru in Dec 44-Jan 45. The remainder consisted of American, Norwegian, and Czech nationals who had been taken to Taiwan aboard Hokusen Maru.

Seven or eight survivors of the Oryoku Maru/Enoura Maru/Brazil Maru journeys of Dec 44-Jan 45 were brought to Fukuoka 17 from Fukuoka 22 in late Feb or early March 45. Two remained at the camp(#1886, #1892) but the others plus several of the original group of American officers including Maj. John Mamerow, were sent to Mukden, Manchuria on 25 April 1945.

In June 1945 a group of about 100 Australians (#'s above 1893) were transferred from camp Fukuoka camp 13-D, Oita, to Fukuoka 17. These men had arrived in Japan in Sept 1944 aboard Rashin Maru.

Fukuoka Camp 17 was liberated on 2 September 1945.

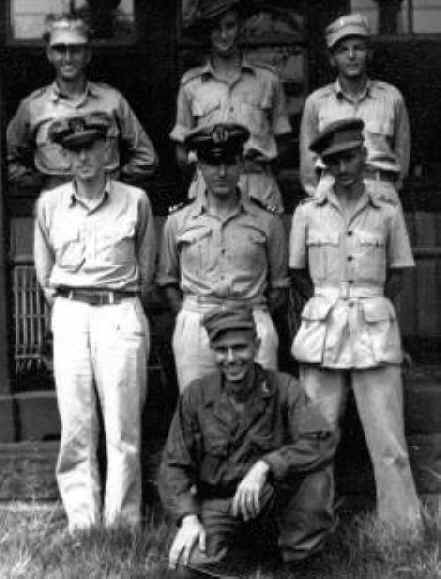

POW Recovery Team Liberators 1945

Lt. Don L. Christison, kneeling, left

Lt. D. L. Christison, back row, middle officer; Lt. Ed Little, standing front, far left