Washington, D. C. 20006

202-887-5105

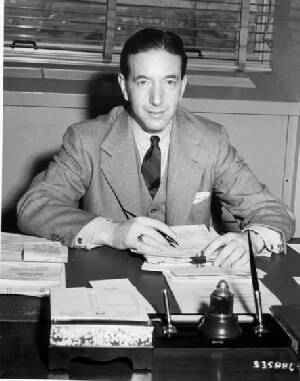

Karl R. Bendetsen

Chairman and Chief Executive, Retired

Government Affairs Consultant

Champion International Corporation

Chairman and Chief Executive, Retired

Government Affairs Consultant

Champion International Corporation

August 5, 1981

Dear Mrs. Baker:

I warmly appreciate your thoughtful letter of August 1, 1981 relative to wartime relocation of persons of Japanese ancestry from the Western Sea Frontier.

I also thank you for sending me a copy of the testimony on behalf of Mr. Dillon S. Myer. I have also perused the other material which you included. It is all very well researched, accurate and illuminating.

I have enclosed a substitute for my original written statement. It has not been revised but has been briefly supplemented on pages 4, 7, 14, 16, 17 and 18.

The Honorable John J. McCloy who was The Assistant Secretary of War during World War II will have submitted a written statement to the Commission. You may wish to write him for a copy. His address is:

The Honorable John J. McCloy

Milbank, Tweed, Hadly & McCloy

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

Milbank, Tweed, Hadly & McCloy

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

I do not believe there is any scintilla of evidence either (a) to support the Commission's preordained conclusions and allegations or (b) of its intention to publish the facts.

I think the remarks of Arthur Goldberg and Abe Fortas are intemperate, slanderous and contemptible.

I would be very interested in knowing what occurred at the hearing in Los Angeles on Tuesday, August 4.

I have enclosed a copy of my letter of transmittal to the Commission of my substitute written statement to which I referred above.

EnclosureWith all good wishes,

Sincerely,

(signed Karl Bendetsen)

Mrs. Lillian Baker

15237 Chanera Avenue

Gardena, California 90249

WRITTEN STATEMENT OF KARL R. BENDETSEN FOR

THE COMMISSION ON WARTIME RELOCATION AND INTERNMENT OF CIVILIANS

Responsive to the request of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Interment of Civilians contained in a letter to Karl R. Bendetsen dated June 22, 1981 (copy attached) and in consonance with his acknowledgment dated June 26, 1981 (copy attached) the following written statement is provided:

I will first comment on the reference found in the attached letters concerning the Aliens Division of the War Department.

During the year 1941, while serving in a staff capacity in the War Department, I was assigned to the newly established office of The Provost Marshal General. I am now unable to recall the date but I believe it was in late summer. There had been no such office since the end of World War I.

My duties were varied although they did include attention to the provisions of the Geneva Convention applicable to prisoners of war and to the need to establish a Prisoner of War Information Bureau in the event war came. These duties also applied to the provisions of facilities by the War Department for housing of such aliens of hostile nations who were regarded by other authorities as dangerous if war came.

The War Department had no jurisdiction or authority over any enemy aliens in the United States excepting only that provided in Executive Order 9066 from and after February 19, 1942 with respect to enemy aliens residing within the Western Defense Command. Such individuals then came under the aegis of the Commanding General of the Western Defense Command and Fourth Army by delegation from The President of the United States.

The office of the Provost Marshal General was then very small and I simply do not recall that it had an Aliens Division or for that matter any section which were extensive enough to be designated as "Divisions." It is not a matter of any consequence or import. I refer to this only because of the exchange of letters.

I believe that from the title of the Commission, it will concern itself among others with the subject of the Aleuts who were evacuated from the Pribilof Islands off the coast of Alaska in the Bering Sea. I had no duties, no assignments nor any authority by delegation or otherwise relating to the Aleuts. I am not familiar with any aspect of that action. I was informed by others that the Aleuts were not self-sustaining and could not become so. They therefore required frequent support and supplies by sea. Because hostilities and the then command of the seas by the Japanese naval forces rendered such support problematical, they were removed to assure their own survival, presumably by the Department of Interior.

I am inclined to believe that the interest of the Commission in asking me for a statement accordingly relates to the evacuation in 1942 of persons of Japanese ancestry from the Western Sea Frontier of the United States under the authority of Executive Order 9066 dated February 19, 1942. In order to be as helpful as I can to the Commission, I will therefore refer in this statement primarily to that subject.

Starting at the beginning, and viewed in the perspective of the months following December 7, 1941, and particularly the winter and spring of 1942, it will be recalled from your general knowledge that the tides of war in the Pacific were running most adversely to the United States. The nation had suffered many reverses. The Japanese in its superbly coordinated and devastating surprise attacks on Pearl Harbor, the Philippines and Singapore had achieved unprecedented successes.

Japanese naval units had also shelled the West Coast with submarine mounted cannon and had bombed military bases in the Aleutian Islands as far east as the military bases of Cold Harbor and Kodiak. Japanese military forces had assaulted and occupied the Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska. The U.S. Pacific fleet had been crippled. Japanese naval forces dominated the entire Pacific. The situation of the United States was grim and uncertain.

It will also be recalled that the preponderance of all persons of Japanese ancestry residing on the West Coast of the United States had for the most part largely concentrated themselves into readily identifiable clusters.

The legal restrictions of the applicable laws of the United States and California, Oregon and Washington states then in force, combined in influence to further a tendency toward a separate way of life. The Alien Exclusion Acts (which I had always felt embodied very bad policy with which I was never in sympathy) nevertheless were in force over many decades. The fact was that under these Acts, Japanese (who migrated to the United States from Japan) were not permitted to intermarry with U.S. citizens, were not permitted to own land or to take legal title to land and could not become citizens. Over the years, assimilation of the migrants and their families was retarded. These laws did not promote assimilation to a desirable extent.

Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, as Commanding General of the Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, was responsible for the defense of the Western Sea Frontier, including Alaska. The War Department reflected the expressed concerns of General DeWitt and the FBI, and the Justice Department conveyed their great unease and anxiety to The President himself.

An Assistant Attorney General, Mr. James Henry Rowe, Jr., was the principal Justice Department action officer responsible in this field. Mr. Tom Clark (later the Attorney General of the United States and Justice of the Supreme Court) was the Special Representative of the Department of Justice on the West Coast in Los Angeles. His duties then concerned only this subject.

It is widely known and appreciated that Justice Clark himself was a man of compassion and understanding, not given to rash judgments. He knew firsthand that the situation had become a powder keg and he saw no alternative to the decision in the national interest and security and indeed of all concerned in these tense, explosive and trying times, other than to bring about the evacuation of persons of Japanese ancestry then resident along the Sea Frontier to the interior.

Unscrupulous persons imposed on the Japanese residents in southern California. This led to reports that all had lost all their properties. This was not so. A few of them were exploited. During the evacuation, extraordinary measures were taken to preserve their properties.

It will also be remembered by some that during 1940 and early 1941, units of U.S. Marine Reserves and of the National Guard from Arizona, California, Oregon and Washington has been deployed and stationed in the Philippines. These units had been decimated by the Japanese military forces during their conquest of the Philippines. As prisoners of war, U.S. military and civilian personnel, as well as Filipinos were treated with brutality. Many died in captivity as a result. All this had become widely known in the United States. Anti-Japanese feeling was intense, particularly in the West Coast states. The situation which arose from these reports created a powder keg. Violence was near at hand.

General DeWitt, after conferring with various advisors, communicated with General Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the Army, that he felt he could not provide for the security of the Sea Frontier, its sensitive installations, the vital manufacturing establishments, and the harbor facilities; train military personnel and units newly organized; and at the same time deal with inchoate civil violence unless effective means of bringing the deteriorating situation under control could be found.

The Western Defense Command had been designated as a military Theatre of Operations. The Pacific battlefront was ominously near and U.S. defenses were then meager. The Pacific Ocean sealanes were dominated by the Japanese Naval forces.

I was ordered by my superiors in the War Department to proceed to the headquarters of General DeWitt to confer with him and his staff. I made many such trips in December, January and February. I became a "commuter." My capacity was to act as a liaison officer.

My assignment was to gather facts and convey General DeWitt's analyses to his superiors in Washington. Each time I returned from the Presidio I would brief General Gullion, the Provost Marshal General, the Chief of Staff, The Assistant Secretary of War (Mr. McCloy), Mr. James Rowe of Justice and others.

It had not occurred to me that there would be an evacuation or that I would be assigned to General DeWitt's command with duties related to an evacuation of persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. I did not recommend such action. I was not asked my opinion except once during a conference with then Senator Truman. I did not express it, as will shortly be related. Certainly, I did not seek such an assignment and would not have desired it.

I did my best as a staff officer, accurately to reflect the concerns of General DeWitt and his staff, of the FBI, of Sea Frontier and that he had concluded after deep thought that the action which President Roosevelt ultimately took was a regrettable but absolute necessity.

Ultimately, an Executive Order was prepared in the Justice Department, not in the War Department. No such order could have been presented to The President of the United States without the full approval of the Attorney General of the United States, Mr. Francis Biddle. The Executive Order thus prepared became Executive Order No. 9066, dated February 19, 1942.

Shortly after Executive Order 9066 was issued, I was again sent to the headquarters of the Western Defense Command at the Presidio of San Francisco. While I was there, The Honorable John J. McCloy, The Assistant Secretary of War, and the Chief of Staff of the Army (General Marshall) were conferring with General DeWitt.

I completed the special assignment which I had been sent to do. I had paid my departure respects to General DeWitt's Chief of Staff, General (Allison J.) Barnett, and left without seeing General DeWitt or his conferees, for the San Francisco airport, to board a United Airlines flight for Washington, D.C. And as I was about to board the aircraft, an aide of General DeWitt drove out on the airfield in a military car. He came to me and said, "Bendetsen, you're wanted at the Presidio." I asked, "What has happened?" He replied, "I don't know what has happened, but General DeWitt, General Marshall and Mr. McCloy are together and they are waiting for you. My orders were to come out and get you. I told the airline that General DeWitt had asked that the flight be held, if necessary." We drove immediately to the Presidio. I was ushered into the august presence of The Assistant Secretary of War, Mr. McCloy, Generals Marshall and DeWitt.

To my great surprise, General DeWitt then said, "Bendetsen, as you know, The President has signed Executive Order 9066, providing for the evacuation from the Sea Frontier of all persons of Japanese ancestry. Mr. McCloy, General Marshall and I feel that you are the best choice to be in charge of this difficult assignment."

General DeWitt then added: "There is no time to lose. You are designated as an Assistant Chief of Staff of the Fourth Army and Western Defense Command. I will create the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA). You will be the commanding officer of the WCCA. You will also be appointed as an Assistant Chief of Staff of my general staff. In this capacity you will be empowered to issue orders in my name to yourself as commanding officer of the WCCA. You will thus have full power and authority to act." He then called in his sergeant (clerk) who operated the stenotype and dictated his order:

I hereby delegate to you all and in full my powers and authority under Executive Order 9066, which in turn have been delegated by The President to the Secretary of War, by the Secretary of War to the Chief of Staff, and by the Chief of Staff to the Commanding General of the Western Defense Command and Fourth Army. All rules and regulations of the Fourth Army over which I have any control or authority, you have authority to suspend, as in your judgment may be necessary. You will take this action forthrightly, you will establish a separate headquarters, you will have full authority to call upon all Federal civilian agencies as provided in the Executive Order and to call for assistance and cooperation of the State authorities as The President has in turn asked the Governors of the states concerned to provide. You will do this with a minimum of disruption of the logistics of military training, operations and preparedness, and with a minimum of military personnel, and with due regard for the protection, education, health and welfare of all of the Japanese persons concerned. You will, to the maximum, take measures to induce them to relocate voluntarily under your authority, in areas east of the Cascades, Sierra Nevadas, and north of the southern half of Arizona and New Mexico, so that the burden upon them will be at a minimum. You will make known that the Army has no wish to retain them at any time for more than temporary custody. It would be contrary to the philosophy and desires of the Army to do otherwise. These measures are for the protection of the nation in a cruel and bitter war, and for the protection of the Japanese people themselves. You will use all measures to protect the personal property of Japanese, including crops.There were 24 temporary assembly centers which were selected, established and equipped along the West Coast. I later selected the sites for the ten relocation centers to which those Japanese persons who had not already relocated in the interior could be moved pending their relocation and absorption into the economies of the interior states.

The procedure followed was to designate evacuation zone control areas. I called upon all of the Federal Agencies for assistance, including the Federal Reserve and the banks in the Federal Reserve system. I used agencies of the Departments of Agriculture and Interior. Such authority had been delegated by President Roosevelt in Executive Order 9066, as above stated.

General DeWitt's order to me directed in very specific words that "You will protect their crops, and harvest them and see that they are paid for their produce." We harvested all crops, we sold them, we deposited the money to their respective accounts. We kept families together.

As indicated, we established 24 interim family assembly centers. The families were not separated. We made special arrangements aboard the trains for their protection and for their reasonable comfort and health. Step by step, we evacuated people from designated evacuation zones into the assembly centers which had been prepared to house them.

Under my direction the relocation centers were built and furnished with residential equipment, bedding, beds, dressers, tables, chairs, schoolrooms and teaching equipment, infirmaries, dormitories, bathing and sanitary facilities, as well as kitchens and dining halls, fully equipped.

When all those who had not resettled themselves had been moved to relocation centers and all arrangements had been made for training of personnel for full staffing of these centers, the Army by Presidential order then turned over the centers to the War Relocation Authority. It was headed by a man named Dillon Myer.

The following is a summary:

First, about their assets, their lands (Nisei could own land), their possessions, their bank accounts and other assets, their household goods, their growing crops -- nothing was confiscated. Their accounts were left intact. Their household goods were inventoried and stored. Warehouse receipts were issued to the owners. Much of it was later shipped to them at government expense, particularly in the cases of those families who relocated themselves in the interior, accepted employment and established new homes.

Lands were farmed, crops harvested, accounts kept of sales at market and proceeds deposited to the respective accounts of the owners.

Second, it was never intended by Executive Order 9066 and certainly not by the Army that the Japanese themselves be held in relocation centers. The sole objective was to bring about relocation away from the Sea Frontier. Japanese were urged to relocate voluntarily on their own recognizance and extensive steps were taken to this end. The desire was to relocate them so that they could usefully and gainfully continue raising their families and educate their children while heads of families and young adults became gainfully employed. They were to be free to lease land, raise and harvest crops, go into business. They were not to be restricted so long as they did not seek to remain or seek to return to the war "frontier" of the West Coast.

In furtherance, from the very beginning I initiated diligent measures to urge the Japanese families to leave with the help and funding (whenever needed) of the WCCA (Wartime Civil Control Administration) on their own recognizance and resettle east of the mountains. To this end, I conferred with the governors of the seven contiguous states east of the mountains. I called a Governors' Conference at Salt Lake City. I invited them to urge attendance by members of their cabinets, by members of their legislatures and by the mayors of their communities. It was a large and successful conference. I advised them in full, sought their full cooperation, asked them to inform their citizens and to welcome and help the evacuees to feel welcome without restrictions, to become members of the inland communities and schools and to help them find employment and housing. I told them that these people would become a most constructive segment of their respective populations. Those who resettled certainly did. Where needed, I told them that the WCCA would provide financial support for a limited period.

Further to this end, I conferred with the elders of each major Japanese community along the Pacific Coast, wherever they were. I carefully explained all this to them. I expressed deep regret that this unfortunate situation had arisen. I urged them to persuade their fellow Japanese to leave before the evacuation to assembly centers began and while it was proceeding. I assured them that the WCCA would provide escort, if requested, for those who felt insecure. We organized convoys and shipped to those who had resettled their stored possessions. I urged their cooperation. To their eternal credit, it was given.

This phase of resettlement from the temporary assembly centers came to a regrettable and necessary halt. Hostility toward the Japanese in the interior, at first minimal, developed quite suddenly and intensively in the western states of the interior as word of the brutalities committed against U.S. military and civilian forces by the Japanese became generally known.

The protection of the evacuees mandated that such a measure be instituted. I visited each assembly center and discussed the reasons for this with leaders among the evacuees. They fully understood. Assurances were given that unremitting efforts would be taken with state and city officials and with community leaders to deal with and to defuse these attitudes. Further assurances were given that resettlement from the ten relocation centers would resume in due course. Fortunately, within four to five months these hostile feelings moderated due to the good offices of the officials, community leaders and the press of these interior states. The process of relocation from the assembly centers to the relocation centers resumed. The WCCA resumed its actions to foster relocation or more properly "resettlement" directly from the relocation centers.

Over four thousand took advantage of the opportunity to leave on their own recognizance with WCCA help in the first three to four months following March 1942.

Persons of Japanese ancestry along the Western Sea Frontier were not interned. Internment was never ordered. There was no confiscation. The intention and purpose was to resettle these persons east of the mountain ranges of the Cascades and Sierra Nevadas, away from the Sea Frontier and away from the relatively open boundaries between Mexico and the states of Arizona and New Mexico.

Some readers may find it useful for reference purposes to here describe the coverage of the Official Report date June 5, 1943. With others I assisted in the preparation of that report.

The letter of transmittal of the Report to the Chief of Staff of the Army consisted of ten paragraphs, in itself a brief summary. It is included in the Official Report.

The Library of Congress card catalogue reference under the letter "U" is officially titled:

United States Army, Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, Japanese Evacuation from the West CoastThe Report is in nine parts consisting of 28 chapters with extensive reference materials and special reports appended. These reference materials included the reports of many Federal civilian agencies which had been placed under General DeWitt's direction by order of The President. In addition, various primary source materials were selected and bound together. Two of these special reports, for example, were from the Farm Security Administration of the Department of Agriculture and the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, a part of the Federal Reserve system. The special reports numbered twelve in all.

The Official Report, together with all of its appended and supplemental materials, was filed in the Library of Congress and remains there. Other sets were filed in the War Department, in the custody of the Adjutant General (now the Department of Army).

General DeWitt recommended that his Report and all of its supplements be declassified and published immediately. His recommendation was adopted. At the same time, he also recommended that the type which had been set for the printing of the Report, special reports and appendixes remain intact for additional printings, so that distribution of the Report and its associated material could be quickly made available to Federal and state agencies, public libraries, colleges and universities. This was done.

Chapter Two of the Report discusses the need for military control and for evacuation. Chapter Three discusses the establishment of wartime civil control under Executive Order 9066. Chapter Four discusses the emergence of controlled evacuation. Chapter Five discusses the separation of jurisdiction over the evacuation on the one hand and relocation on the other.

Subsequent chapters discuss the evacuation methods, the organization and functions of the cooperating Federal agencies.

The Official Report provides in considerable detail the nature, characteristics, etc. of the Japanese communities along the West Coast. It is urged that the Commission study the Official Report and in so doing give due weight to these details, particularly so as to understand the context and setting. It would aid in comprehending the then perspective. To evaluate these past events in the perspectives of today would not be useful.

In the concluding paragraphs of the Report, General DeWitt states that the agencies under his command, military and civilian alike, as well as the efforts of the cooperating Federal agencies which had been placed under his direction "responded to the difficult assignment devolving upon them with unselfish devotion to duty." The paragraph (8) goes on to state: "To the Japanese themselves great credit is due for the manner in which they * * * responded to and complied with the orders of exclusion."

Within the Western Defense Command, resident aliens who were German or Italian were subject to internment. Hearing boards were established. The intelligence agencies such as the FBI and the Naval Intelligence designated those who were regarded as dangerous. Such individuals were given notice, a hearing board was convened, the individual was present, he was entitled to counsel, a reporter produced the entire record. These records were ultimately reviewed in each case by General John L. DeWitt who made the final decision with regard to whether the individual concerned would or would not be interned.

I had officially conveyed to Mr. Dillon Myer, head of the War Relocation Authority (after I had fully briefed him and his staff) full responsibility and accountability for the ten relocation centers in May of 1943.

I was then ordered to report to the Chief of Staff of the Supreme Commander (Designate) located on St. James Square in Norfolk House, London. This was the Combined U.S./British Headquarters which had the duty of planning Operation Overlord, the cross-channel invasion of 1944. The Commanding General had not yet been selected or appointed. This did not happen until sometime later, of course. As everyone knows, General Dwight D. Eisenhower became the Supreme Commander, Allied Forces. The headquarters to which I reported carried the abbreviation C.O.S.S.A.C. (Chief of Staff of the Supreme Allied Commander). My permanent station then became Norfolk House, St. James, London.

In conclusion, I would add that it is manifestly unfair to judge in today's perspective the events hereinbefore described which followed the sneak attacks on Pearl Harbor, the Philippines and Singapore, as well as the destruction of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The sweeping condemnations recently made of the responsible officials cannot be condoned on any basis. They were each faced with impelling necessity. The slurs and slanders of men who are above reproach demeans the character of those who cast them. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, then President of the United States, who made the ultimate decision was a man of compassion and integrity. His chief legal advisor, Attorney General Francis Biddle was also a man of compassion, well and highly regarded for his balanced judgment.

The Honorable Henry Stimson, then Secretary of War who had been the Secretary of State, was a man of great breadth and tolerance. His place in history bespeaks his humane qualities.

Who can responsibly characterize these men, as well as Earl Warren, the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court as racists, as men of no compassion? When Chief Justice Warren was Governor of California, he reluctantly concluded that there was no alternative to the action taken.

The Honorable John J. McCloy who then was The Assistant Secretary of War and a man of towering stature, tolerance, compassion and discretion came to the same conclusion.

General George C. Marshall, then the Chief of Staff to The Secretary of War is well remembered for the Marshall Plan which generously supported recovery of the war torn nations of Western Europe, including Germany, our enemy. President Truman and General Marshall strongly supported General Douglas MacArthur who devoted himself to the rebuilding of our former enemy, Japan, notwithstanding the fact that members of U.S. forces in their hands as prisoners of war were subjected to torture and brutality.

The circumstances then prevailing bear no remote relationship to these times.

I trust the foregoing will prove helpful to the Commission whose duty it is carefully to consider and make public this authoritative statement.

-- Table of

Contents --