OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS

WASHINGTON

MEMORANDUM for Mr. Tamm

SUBJECT: The Japanese Problem

There is transmitted herewith a copy of a report on the Japanese Question which was prepared by Lieutenant Commander K. D. Ringle, U.S.N.

This report was prepared at the request of the Office of Naval Intelligence following the statement by Mr. C. B. Munson, in his survey of Japanese on the West Coast, that Lieutenant Commander Ringle was particularly well acquainted with the Japanese problem.

Although it does not represent the final and official opinion of the Office of Naval Intelligence on this subject, it is believed that this report will be of

interest to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

H. E. Keisker,

Commander, U.S.N.R.

DECLASSIFICATION ON 5/14/85

BY 1678RFP IAG

Mr. E. A. Tamm

Federal Bureau of Investigation

U. S. Department of Justice

Washington, D. C.

Copy to:

Alien Enemy Control Unit, Department of Justice

Special Defense Unit, Department of Justice

RINGLE REPORT

BIO/ND11/EF37/A8-5

Serial LA/1055/re

BRANCH INTELLIGENCE OFFICE

ELEVENTH NAVAL DISTRICT

FIFTH

FLOOR, VAN

NUYS BUILDING

SEVENTH AND SPRING STREETS

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA

CONFIDENTIAL

From: Lieutenant Commander K.D. RINGLE, USN.

To: The Chief of Naval Operations.

Via: The Commandant, Eleventh Naval District.

Subject: Japanese Question, Report on.

Reference:

(b) Reports of Mr. C.B. Munson, Special Representative of the State Department, on Japanese on the West Coast, dated Nov. 7, 1941, and Dec. 20, 1941.

(c) NNI 119 Report, file BIO/ND11/EF37/A8-2, serial LA/861 of 3/27/41, subject-NISEI.

(d) NNI 119 Report, file BIO/ND11/EF37/A8-2, serial LA/5223 of 11/4/41, subject-NISEI.

(e) NNI 119 Report, file BIO-LA/ND11/EF37/P8-2, serial LA/6524 of 12/12/41, subject-HEIMUSHA-KAI.

(f) NNI 119 Report, file BIO-LA/ND11/EF37/P8-2, serial LA/417 of 1/5/42, subject-KIBEI Organizations and Activities.

(g) Dept. of Commerce Bulletin, Series P-3, Number 23, dated 12/9/41.

Enclosures:

(B) F.B.I., L.A. Report re Japanese Activities, Los Angeles, dated Jan. 20, 1942.

1. In accordance with paragraph 2 of reference (a), the following views and opinions with supporting facts and statements are submitted.

I. OPINIONS.

The following opinions, amplified in succeeding paragraphs, are held by the writer:

(a) That within the last eight or ten years the entire "Japanese question" in the United States has reversed itself. The alien menace is no longer paramount, and is becoming of less importance almost daily, as the original alien immigrants grow older and die, and as more and more of their American-born children reach maturity. The primary present and future problem is that of dealing with those American-born United States citizens of Japanese ancestry, of whom it is considered that least seventy-five per cent are loyal to the United States. The ratio of those American citizens of Japanese ancestry to alien-born Japanese in the United States is at present almost 3 to 1, and rapidly increasing.

(b) That of the Japanese-born alien residents, the large majority are at least passively loyal to the United States. That is, they would knowingly do nothing whatever to the injury of the United States, but at the same time would not do anything to the injury of Japan. Also, most of the remainder would not engage in active sabotage or insurrection, but might well do surreptitious observation work for Japanese interests if given a convenient opportunity.

(c) That, however, there are among the Japanese both alien and United States citizens, certain individuals, either deliberately placed by the Japanese government or actuated by a fanatical loyalty to that country, who would act as saboteurs or agents. This number is estimated to be less than three per cent of the total, or about 3500 in the entire United States.

(d) That of the persons mentioned in (c) above, the most dangerous are either already in custodial detention or are members or such organizations as the Black Dragon Society, the Kaigan Kyokai (Navy League), or the Heimusha Kai (Military Service Men's League), or affiliated groups. The membership of these groups is already fairly well known to the Naval Intelligence service or the Federal Bureau of Investigation and should immediately be placed in custodial detention, irrespective of whether they are alien or citizen. (See references (e) and (f).)

(e) That, as a basic policy tending toward the permanent solution of this problem, the American citizens of Japanese ancestry should be officially encouraged in their efforts toward loyalty and acceptance as bona fide citizens; that they be accorded a place in the national effort through such agencies as the Red Cross, U.S.O., civilian defense, and even such activities as ship and aircraft building or other defense production activities, even though subject to greater investigative checks as to background and loyalty, etc., than Caucasian Americans.

(f) That in spite of paragraph (e) above, the most potentially dangerous element of all are those American citizens of Japanese ancestry who have spent the formative years of their lives, from 10 to 20, in Japan [Kibei] and have returned to the United States to claim their legal American citizenship within the last few years. These people are essentially and inherently Japanese and may have been deliberately sent back to the United States by the Japanese government to act as agents. In spite of their legal citizenship and the protection afforded them by the Bill of Rights, they should be looked upon as enemy aliens and many of them placed in custodial detention. This group numbers between 600 and 700 in the Los Angeles metropolitan area and at least that many in other parts of Southern California.

(g) That the writer heartily agrees with the reports submitted by Mr. Munson, (reference (b) of this report.)

(h) That, in short, the entire "Japanese Problem" has been magnified out of its true proportion, largely because of the physical characteristics of the people; that it is no more serious than the problems of the German, Italian, and Communistic portions of the United States population, and, finally that it should be handled on the basis of the individual, regardless of citizenship, and not on a racial basis.

(i) That the above opinions are and will continue to be true just so long as these people, Issei and Nisei, are given an opportunity to be self-supporting, but that if conditions continue in the trend they appear to be taking as of this date; i.e., loss of employment and income due to anti-Japanese agitation by and among Caucasian Americans, continued personal attacks by Filipinos and other racial groups, denial of relief funds to desperately needy cases, cancellation of licenses for markets, produce houses, stores, etc., by California State authorities, discharges from jobs by the wholesale, unnecessarily harsh restrictions on travel, including discriminatory regulations against all Nisei preventing them from engaging in commercial fishing -- there will most certainly be outbreaks of sabotage, riots, and other civil strife in the not too distant future.

II. BACKGROUND.

(1) In order that the qualifications of the writer to express the above opinions may be clearly understood, his background of acquaintance with this problem is set forth.

(a) Three years' study of the Japanese language and the Japanese people as a naval language student attached to the United States Embassy in Tokyo from 1928 to 1931.

(b) One year's duty as Assistant District Intelligence Officer, Fourteenth Naval District (Hawaii) from July 1936 to July 1937.

(c) Duty as Assistant District Intelligence Officer, Eleventh Naval District, in charge of Naval Intelligence matters in Los Angeles and vicinity from July 1940 to the present time.

(2) As a result of the above, the writer has over the last several years developed a very great interest in the problem of the Japanese in America, particularly with regard to the future position of the United States citizen of Japanese ancestry, and has sought contact with certain of their leaders. He has likewise discussed the matter widely with many Caucasian Americans who have lived with the problem for years. As a result, the writer believes firmly that the only ultimate solution is as outlined in paragraphs I(e) and I(h) above; namely, to deliberately and officially encourage the American citizen of Japanese ancestry in his efforts to be a loyal citizen and to help him to be so accepted by the general public.

III. ELABORATION OF OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN PARAGRAPH I.

(1) For purposes of brevity and clearness, four Japanese words in common use by Americans as well as Japanese in referring to these people will be explained. Hereafter these words will be used where appropriate.

ISSEI (pronounced ee-say) meaning "first generation." Used to refer to those who were born in Japan; hence, alien Japanese in the United States.

NISEI (pronounced nee-say) meaning "second generation." Used for those children of ISSEI born in the United States.

SANSEI (pronounced san-say) meaning "third generation." Children of NISEI.

KIBEI (pronounced kee-bay) meaning "returned to America." Refers to those NISEI who spent all or a large portion of their lives in Japan and who have now returned to the United States.

(2) The one statement in paragraph I(a) above which appears to need elaboration is that seventy-five per cent or more of the Nisei are loyal United States citizens. This point was explained at some length in references (c) and (d). The opinion was formed largely through personal contact with the Nisei themselves and their chief organization, the Japanese American Citizens League. It was also formed through interviews with many people in government circles, law-enforcement officers, business men, etc., who have dealt with them over a period of many years. There are several conclusive proofs of this statement which can be advanced. These are ---

(a) The action taken by the Japanese American Citizens League in convention in Santa Ana, California, on January 11, 1942. This convention voted to require the following oath to be taken, signed, and notarized by every member of that organization as a prerequisite for membership for the year 1942, and for all members taken into the organization in the future:

"I, __________, do solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I hereby renounced any other allegiances which I may have knowingly or unknowingly held in the past; and that I take this obligation freely without any mental observation or purpose of evasion. So help me God."

(b) Many of the Nisei leaders have voluntarily contributed valuable anti-subversive information to this and other governmental agencies. (See reference (d) and enclosure (B).)

(c) That the Japanese Consular staff, leaders of the Central Japanese Association, and others who are known to have been sympathetic to the Japanese cause do not themselves trust the Nisei.

(d) That a very great many of the Nisei have taken legal steps through the Japanese Consulate and the Government of Japanese to officially divest themselves of Japanese citizenship (dual citizenship), even though by so doing they become legally dead in the eyes of the Japanese law, and are no longer eligible to inherit any property which they or their family may have hold in Japan. This opinion is further amplified in references (c) and (d).

(3) The opinion expressed in paragraph I(b) above is based on the following: The last Issei who legally entered the United States did so in 1924. Most of them arrived before that time; therefore, these people have been in the United States at least eighteen years, or most of their adult life. They have their businesses and livelihoods here. Most of them are aliens only because the laws of the United States do not permit them to become naturalized. They have raised their children, the Nisei mentioned in paragraph (1) above, in the United States; many of them have gone in the United States army. Exact figures are not available, but the local Military Intelligence office estimates that approximately five thousand Nisei in the State of California have entered the United States army as a result of the Selective Service Act. It does not seem reasonable that these aliens under the above conditions would form an organized group for armed insurrection or organized sabotage. Insofar as numbers go, there are only 48,697 alien Japanese in the eight western states.

The following paragraph quoted from an Associated Press dispatch from Washington referring to the registration of enemy aliens is considered most significant on this point: "The group which must register first comprises the 135,843 enemy aliens in the western command -- Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, and Washington. The group includes 26,255 Germans, 60,905 Italians, and 48,697 Japanese." It is assumed that the foregoing figures are based either on the 1940 census or the alien registration which was taken the latter part of 1940.

There are two factors which must be considered in this group of aliens: First, this group includes a sizeable number of "technical" aliens; that is, those who, although Japanese born and therefore legally aliens, entered the United States in infancy, grew up here, and are at heart American citizens. Second, the parents of the Nisei, mentioned in paragraph I(f), should be considered as those who are most loyal to Japan, since they themselves are the ones who sent their children to be education and brought up entirely in the Japanese manner.

(4) Paragraph I(c) needs no further elaboration.

(5) Paragraph I(d) has been elaborated at length in references (e) and (f).

(6) Elaboration of paragraph I(e). The United States recognizes these American-born Orientals as citizens, extends the franchise to them, drafts them for military service, forces them to pay taxes, perform jury duty, etc., and extends to them the complete protection afforded by the Constitution and Bill of Rights, and yet at the same time has viewed them with considerable suspicion and distrust, and so far as it is known to the writer, has made no particular effort to develop their loyalty to the United States, other than to permit them to attend public schools. They are segregated as to where they may live by zoning laws, discriminated against in employment and wages, and rebuffed in nearly all their efforts to prove their loyalty to the United States, yet at the same time those of them who grow to about the age of 16 years in the United States and then go to Japan for a few years of education find themselves viewed with more suspicion and distrust in that country than they ever were in the United States, and the majority of them return after a short time thoroughly disillusioned with Japan and more than ever loyal to the United States.

It is submitted that the only practical permanent solution of this problem is to indoctrinate and absorb these people, accept them as an integral part of the United States population, even though they remain a racial minority, and officially extend to them the rights and privileges of citizenship, as well as demanding of them the duties and obligations.

Furthermore, if some such steps are not taken, the field for proselyting and propaganda among them is left entirely to Japanese interests acting through Consulates, Consular agents, so-called "cultural societies", athletic clubs, Buddhist and Shinto priests -- who through a quirk in the United States immigration laws may and have entered the country freely, regardless of exclusion laws or quota as "ministers of religion" -- trade treaty aliens, steamship and travel agencies, "goodwill" missions, etc. It is well known to the writer that his acquaintance with and encouragement of Nisei leaders in their efforts towards Americanization was a matter of considerable concern to the former Japanese Consul at Los Angeles.

It is submitted that the Nisei could be accorded a place in the national war effort without risk or danger, and that such a step would go farther than anything else towards cementing their loyalty to the United States. Because of their physical characteristics they would be most easily observed, far easier than doubtful citizens of the Caucasian race, such as naturalized Germans, Italians, or native-born Communists. They would, of course, be subject to the same or more stringent checks as to background than the Caucasians before they were employed.

(7) No elaboration is considered necessary for paragraphs I(f), I(g), and I(h).

(8) Elaboration of paragraph I(i). The opinion outlined in this paragraph is considered most serious and most urgent. There already exists a great deal of economic distress due to such war conditions as frozen credits and accounts, loss of employment, closing of businesses, restrictions on travel, etc. This condition is growing worse daily as the savings of most of the alien-dominated families are being used up. As an example, the following census, taken by missionary interests, of alien families in the fishing village on Terminal Island is submitted:

"How long can you maintain your family without work?"

| Immediate attention | --- |

9 families |

| 1 month | --- | 52 families |

| 2 months | --- | 64 families |

| 3 months | --- | 81 families |

| 4 months | --- | 32 families |

| 5 months | --- | 20 families |

| 6 to 10 months | --- | 129 families |

| Over 10 months | --- | 90 families |

| Total | --- | 477 families. |

Large numbers of people, both Issei and Nisei, are idle now, and their number is growing. Children are beginning to be unable to attend school through lack of food and clothing. There have been already incipient riots brought about by unprovoked attacks by Filipinos on persons of the Japanese race, regardless of citizenship. There is a great deal of indiscriminate anti-Japanese agitation stirring the white population by such people as Lail Kane, former Naval Reserve officer, James Young, Hearst correspondent, in his series of lectures, and John B. Hughes, radio commentator, transcripts of whose broadcasts are submitted as enclosure (A).

There are just enough half truths in these articles and statements to render them exceedingly dangerous and to arouse a tremendous amount of violent anti-Japanese feeling among Caucasians of all classes who are not thoroughly informed as to the situation. It is noted that in these broadcasts, lectures, etc., there are no distinctions made whatever between the actual members of the Japanese military forces in Japan and the second and third generation citizens of Japanese ancestry born and brought up in the United States. It must also be remembered that many of the persons and groups agitating anti-Japanese sentiment against the Issei and Nisei have done so for some time from ulterior motives -- notable is the anti-Japanese agitation by the Jugo-Slav fishermen who frankly desire to eliminate competition in the fishing industry.

It is further noted that according to the local press, Congressman Leland M. Ford has introduced a bill in Congress providing for the removal and internment in concentration camps of all citizens and residents of Japanese extraction, which according to the census figures would amount to about 127,000 people of all ages and sexes in the continental United States, plus an additional 158,000 in Hawaii and other territories and possessions, excluding the Philippines, (see reference (g) for population breakdown). It is submitted that such a proposition is not only unwarranted but very unwise, since it would undoubtedly alienate the loyalty of many thousands of persons who would otherwise be entirely loyal to the United States, would add the extra burden of supporting and guarding these people to the war effort, would disrupt many essential businesses, notably that of the growing and supplying of foodstuffs, and would probably cause a widespread outbreak of sabotage and riot.

IV. RECOMMENDATIONS.

(1) Based on the above opinions, the following recommendations for the handling of this situation are submitted:

(a) Provide some means whereby potentially dangerous United States citizens may be held in custodial detention as well as aliens. It is submitted that in a military "theater of operations" -- which at present includes all the West coast -- this might be done by review of individual cases by boards composed of members of Military Intelligence, Naval Intelligence, and the Department of Justice.

(b) Under the provisions of (a) above, held in custodial detention such United States citizens as dangerous Kibei or German, Italian, or other subversive sympathizers and agitators as are deemed dangerous to the internal security of the United States.

(c) Similar procedure to be followed in cases of aliens -- not only Japanese, but other aliens of whatever nationality, whether so-called "friendly" aliens or not. This suggestion is made since it is believed that there exist other aliens -- Spanish, Mexican, Portuguese, Slavonian, French, etc., who are active Axis sympathizers.

(d) Other suggestions as listed in reference (a).

(e) In the cases of persons held in custodial detention, whether alien or citizen, see that some definite provision is made for the support of their dependent families. This could be done by:

(1) Releasing certain specified amounts from these people's "frozen" funds monthly for the support of these dependents.

(2) Making definite provisions through relief funds for the support of such dependents, so that they will not become either public charges or embittered against the United States, and themselves dangerous to the internal peace and security of the country.

(f) In the interest of national unity and internal peace and security some measures should be instituted to restrain agitators of both radio and press who are attempting to arouse sentiment and bring about action -- private, local, state, and national, official and unofficial, against these people on the basis of race alone, completely neglecting background, training, and citizenship.

DIO(2)

DECLASSIFICATION ON 5/15/85

BY 1678RFP/AG

CONFIDENTIAL

BIO/ND11/EF37/A8-5

SUBJECT: Japanese Menace on Terminal Island, San Pedro, California.

REFERENCE: (a) Report on subject prepared by Counter Intelligence Section, ONI, January 18, 1942.

PREPARED BY: Lieut. Comdr. K. D. RINGLE, USN.

DATE: February 7, 1942.

1. The land on which the Japanese colony on Terminal Island is established is owned by the City of Los Angeles and administered under the Harbor Department. This land, including the sites of the various fish canneries and the waterfront and moorings at Fish Harbor, has been leased by the City of Los Angeles to the fish canneries for many years. The canneries in turn built the houses and barracks now occupied by the Japanese and sub-leased them to the cannery employees.II Japanese Population.

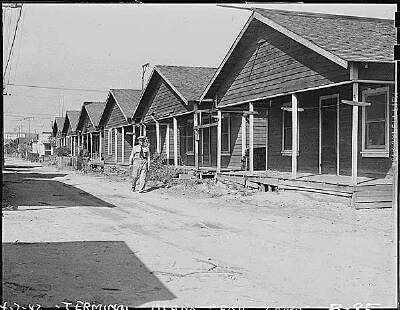

"View of homes from which residents of Japanese ancestry were evacuated on Terminal Island in Los Angeles harbor." (04/07/1942)

This was done so that at any hour of the day or night when fish were brought in, cannery employees could be quickly called to work and the fresh fish processed before any deterioration or spoilage set in. Also, the cannery employees engaged in the actual taking of fish at sea were likewise leased dwellings here. These sub-leases are very short-term leases, subject to quick cancellation if the lessees should cease to be employed by the canneries. It should therefore be self-evident that this entire colony has existed since its inception due to the tolerance, knowing or unknowing, of the Los Angeles city government and the fish packing industry.

1. The total Japanese population, including both alien and American born, is at present about 2500. It is interesting to note in this connection that there are only about 800 aliens, the balance being entirely American-born. Of these 800 about 375 male alien fishermen were taken into custody by the Department of Justice on 2 February 1942, leaving an alien population of about 425 at present, largely women.

2. It will be noted that this is a decrease in Japanese population from that reported in reference (a). Causes for this decrease are as follows:

(a) Due to the unsettled political situation between the United States and Japan during the last two years, a great many of the alien families have returned to Japan.

(b) There have been no replacements arriving from Japan for those who have died or who have moved away.

(c) The American-born children as they come of age have turned to other means of livelihood and have moved away from Terminal Island. This is considered to be a result of the Americanizing influence of their education in the American public schools.

(d) The fish canneries themselves have been gradually replacing a great many of the former Japanese employees, both afloat and ashore by non-Japanese, such as Jugo-Slavs, Filipinos, Negroes, and the like.

3. There does exist in the present population a large element of what is considered to be the most dangerous class of persons of the Japanese race in the United States. This class is composed of those persons born in the United States, sent to Japan in infancy, raised and trained there, and who have returned to the United States within the last four or five years as adults, and who have been permitted entry as American citizens because of their American birth. There are several hundred of this type of person presently residing on Terminal Island and engaged either in the taking or processing of fish. It is felt that these persons constitute the greatest menace of the whole colony to the security of the United States.III The Fishing Fleet.

1. The menace of the so-called Japanese fish boats has been decreased greatly in the last few years, due to the action of the United States authorities in such cases as that of the fish boat Nancy Hanks. It is quite true that formerly there were a number of actual alien-owned and alien-documented vessels operating out of the Port of Los Angeles, paying so-called "light money" for the privilege of so operating. However, largely due to the rigid enforcement of the customs laws, these vessels have either been withdrawn or have changed their documentation to American ownership. In the case referred to of the Nancy Hanks, the customs instituted a suit against the owners for non-payment of duty on fish brought into the United States and sold in the domestic market, by a foreign-owned vessel.IV Analysis of the Hazard to the Security of the United States due to this Japanese Colony on Terminal Island.

In order that these vessels could be documented under the laws of the United States, it was required that at least 51% of the vessel be owned by American citizens, and that an American citizen be master of the vessel. These laws were in the past evaded by having the ownership vested in the American-born children of aliens and by having the American-born master be merely a dummy, the real control of the vessel and her crew being vested in the head of the fishing crew who was known as the "fish boss," who directed all movements of the vessel at sea. The latter practice was common even on those vessels owned by the fish packers themselves. Hence, this evasion of the law was done with the tacit consent and connivance of the fish packing companies, although it is exceedingly doubtful if this can be proved in any court of law.

In the last two or three years, this situation has gradually been rectified by a more rigid inspection and supervision of these vessels by the Customs and the Coast Guard, until at the present time it is doubtful if any of the documented vessels are actually alien-owned or alien-controlled.

Nevertheless, there are a large number of small undocumented vessels used in inshore fishing which are completely alien-owned and alien-controlled, since they do not come within the documentation laws of the United States. These as a rule are the small one and two-man vessels of less than five tons.

Since the outbreak of the war on December 7, 1941, there has been no Japanese, either alien or citizen, permitted to leave the harbor on any fishing vessel, large or small. This was done by the Department of Justice acting through the Immigration Service by telegram received on December 7th, which is quoted in part as follows: "It is important in addition to prevent departure persons of Japanese race claiming United States citizenship." This restriction is still in effect.

1. As has been pointed out, it is very evident that a hazard definitely exists due to the location of this large Japanese colony in the heart of the Los Angeles harbor district. It is considered that this hazard can be broken down as follows:

(a) Physical observation and espionage - 75%.2. An analysis of the above hazards is as follows:

(b) Sabotage - 20%.

(c) Fifth column activity - 5%. By fifth column activity is meant preparation for and assistance to any attempted attack or invasion from outside sources.

(a) It is evident that observation and espionage has been going forward for a great many years. Therefore, it is evident that the physical location of all fixed defense works and harbor improvements and the like are already known to the Japanese. These fixed installations would include such items as the exact location and extent of Reeves Field, Naval Operating Base, Fort MacArthur, oil, gas, and power lines, tank farms, marine oil loading terminals, important docks, oil refineries, shipbuilding installations, railway lines and bridges, anti-submarine nets and buoys, harbor approaches, and side to navigation, and the like.

The items which would be of value to the enemy and which these people are in an unexcelled position to observe and report on, are such items as arrival and departure of convoys, including size, strength of escort, and bulk of cargo; troop movements; arrival and departure of major units of the fleet; progress of shipbuilding, including launching and commissioning of men-of-war, as well as merchant marine; progress of construction of Naval Operating Base, including new dry dock and the channel approaches thereto; delivery of new aircraft; the strength or lack of strength of the aerial defenses of the Naval Air Station and Naval Operating Base; and similar matters.

As long as this colony, which contains known alien sympathizers, even though of American citizenship, is allowed to exist in the heart of every activity in the Los Angeles Harbor, it must be assumed that items such as the above are known, observed, and transmitted to the enemy quickly and easily.

(b) Sabotage. The only reason that sabotage is considered to be no more than 20% or the total hazard, is because of the rather rigid and effective guards and protections which have been placed into effect within the last six months. These protective measures included the emptying of marine loading terminals of oil, gasoline, and other inflammables; lights and guards on ships and docks; constant patrol of the waters of the harbor by the Coast Guard and recently by the City Police of Los Angeles and Long Beach; the posting of guards on bridges leading to Terminal Island; the fencing and private guards required under the terms of the contracts by firms engaged in defense work, such as Bethlehem Shipbuilding Company, Los Angeles Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Company, etc.; and the presence of troops in the immediate vicinity.

It should not be inferred from the above that full and adequate protective measures have been placed into effect -- far from it. There still exists a great need for increased police and fire protection and the reduction of possible fire hazards due to the tremendous lumber yards, free-flowing oil wells, exposed water, gas, gasoline, oil and transmission lines, and installations, etc. These hazards are at the moment beyond control of the naval and military authorities, but would serve as ideal objectives for saboteurs having as ready access to them as the Japanese colony on Terminal Island.

(c) Fifth Column Activity. This hazard is considered to be only 5% of the whole, for two reasons: First, this colony is quite concentrated and under constant observation, and can be quickly and immediately surrounded by troops on the spot. Second, because in spite of what has been said previously, there do exist in this colony a great many known and trusted nisei (American citizens of Japanese ancestry), who would immediately resent and combat any such attempt and who are at present acting as observers and informers for the Naval Intelligence Service and the F.B.I.

On the Japanese

Question in the U.S.:

A Compilation of Memoranda

by Lt. Com. Kenneth

Ringle

June 19, 1942

The

accompanying statement of views on the Japanese question in the United

States was prepared by Lt. Com. K. D. Ringle on the basis of his

acquaintance with the problem over a period of years. Commander

Ringle's background and experience with the Japanese include the

following: (a) three years' study of the Japanese language and the

Japanese people as a Naval Language Student attached to the United

States Embassy' in Tokio from 1928 to 1931; (b) one year’s duty as

Assistant District Intelligence Officer, 14th Naval District (Hawaii)

from July, 1936 to July, 1937; (c) Assistant District Intelligence

Officer, 11th Naval District, in charge of Naval Intelligence matters

in Los Angeles and vicinity from July, 1940 to the present time.As a result of the above, Commander Ringle has developed a very great interest in the problems at the Japanese in America, particularly with regard to the future position of the United States citizen of Japanese ancestry. He has sought contact with certain of the nisei leaders. He has likewise discussed the matter widely with many Caucasian Americans who have lived with the problem for years.

The Commander’s statement represents his own personal opinion and does not necessarily reflect the policies of the War Relocation Authority or the Navy Department. It is submitted for purposes of file and information.

CONTENTS

Definitions

General Opinions

Backgrounds

Dual Citizenship

The Nisei

Issei versus Nisei

Americanization of the Nisei

Importance of School Influence

Intense Desire to Conform

A Change in Position of Women

Adoption of Western Dress

Effect of Religion

End of the Caste System

Examples of Economic and Social Ambition

Loyalty of Group

“Fish out of Water"

Nisei Dependence on Issei Waning

Japanese~American Organizations

Japanese Language Schools

Japanese Newspapers

Why Certain of the Kibei Are Dangerous

Procedure for Segregation

Opportunity for Change in Classification

Segregation of Disloyal Aliens

Committee of Loyal Nisei Can Help

Release of Certain Internees Possible

General Effect of Segregation Desirable

Semi-Military Structure Proposed

Suggestions for Work Program (continued)

Suggestions for Insignia

Voluntary Enlistment Should Be Stressed

Plan for Use of Work Corps in Harvesting

Advantages of Harvesting Plan

General Views on Employability of Evacuees

Views on Self-Government

Youth Organizations

Care of Orphans

Buddhism and Shintoism.

Project Newspapers

Documentation

Intelligence Work Within Relocation Centers

ISSEI (pronounced ee-say) meaning "first generation.” Used to refer to those who were born in Japan; hence, alien Japanese in the United States.

NISEI (pronounced nee-say) meaning "second generation.” Used for those children of ISSEI born in the United States.

SANSEI (pronounced san-say) meaning "third generation.” Children of NISEI.

KIBEI (pronounced kee-bay) meaning "returned to America.” Refers to those NISEI who spent all or a large portion of their lives in Japan and who have now returned to the United States.

THE

JAPANESE QUESTION

IN THE UNITED STATES

A Compilation of Memoranda by Lt. Com. K. D. Ringle

GENERAL OPINIONS

(b) That of the Japanese born alien residents, the large majority are at least passively loyal to the United States. That is, they would knowingly do nothing whatever to the injury of the United States, but at the same time would not do anything to the injury of Japan. Most of the remainder would not engage in active sabotage or insurrection, but might well do surreptitious observation work for Japanese interests if given a convenient opportunity.

(c) That, however, there are among the Japanese, both alien and citizen, certain individuals, either deliberately placed by the Japanese government or actuated by a fanatical loyalty to that country, who would act as saboteurs or agents. This number is estimated to be less than three per cent of the total, or about 3500 in the entire United States.

(d) That, of the persons mentioned above, the most dangerous are either already in custodial detention or are members of such organizations as the Black Dragon Society, the Kaigun Kyokai (Navy League), or the Heimusha Kai (Military Service Men's League), or affiliated groups who have not yet been apprehended. The membership of these groups is already fairly well known to the Naval Intelligence and the Federal Bureau of Investigation and should immediately be placed in custodial detention, irrespective of whether they are alien or citizen.

(e) That, as a basic policy tending toward the permanent solution of this problem, the American citizens of Japanese ancestry should be officially encouraged in their efforts toward loyalty and acceptance as bona fide citizens; that they be accorded a place in the national war effort through such agencies as the Red Cross, U.S.O., civilian defense, and even in such activities as ship and aircraft building or other defense production, even though subject to greater investigative checks as to background and loyalty, etc., than Caucasian Americans.

(f) That, despite paragraph (e) above, the most potentially dangerous element of all are those American citizens of Japanese ancestry who have spent a number of the formative years of their lives, from the age of 13 to the age of 20 in Japan and have returned to the United States to claim their legal American citizenship within the last few years. These people are essentially and inherently Japanese and may have been deliberately sent back to the United States by the Japanese government to act as agents. In spite of their legal citizenship and the protection afforded them by the Bill of Rights, they should be looked upon as enemy aliens and many of them placed in custodial detention.

The last issei who legally entered the United States did so in 1924. Most of the alien group arrived before that time; therefore, these people have been in the United States at least eighteen years, or most of their adult life. They have their businesses and livelihoods here. Most of them are aliens only because the laws of the United States do not permit them to become naturalized. They have raised their children in the United States; many of them have been in the United States army.

Exact figures are not available, but the Military Intelligence Office in Los Angeles estimated on June 15, 1942 that approximately five thousand nisei in the State of California have entered the United States army as a result of the Selective Service Act. It does not seem reasonable that these aliens under the above conditions would form an organized group for armed insurrection or organized sabotage. Insofar as numbers go, there are only 48,697 alien Japanese in the eight western states.

(The Associated Press dispatch from Washington referring to the registration of enemy aliens stated: "The group which must register first comprises the 135,843 enemy aliens in the western command -- Arizona, California, Idaho, Utah, Montana, Nevada, Oregon and Washington. The group includes 26,255 Germans, 60,905 Italians, and 48,697 Japanese." It is assumed that the foregoing figures are based either on the 1940 census or the alien registration which was taken the latter part of 1940.)

There are two factors which must be considered in relation to the issei. First, the group includes a sizeable number of "technical" aliens; that is, those who, although Japanese-born and therefore legally aliens, entered the United States in infancy, grew up here, and are at heart American citizens. Second, the parents of the kibei, should be considered as those who are most loyal to Japan, since they are the ones who sent their children to be educated and brought up entirely in the Japanese manner.

I do not consider that merely registering the birth of a child twenty or more years ago with the Japanese consulate is indicative of any subversive intent on the part of the parent. The parents at that time were not at all sure that they would remain all their lives in the United States nor were they sure that the child would be able to enjoy his citizenship here. They wanted to protect the child so that if he so desired, he could at some later date either return to Japan or otherwise benefit from his Japanese citizenship. In many cases this registration was made merely so that he would be eligible for an inheritance from relatives still in Japan. The situation is exactly that which obtains when American parents resident in England register the birth of their child with the American consulate, so that the child can have the benefit of American citizenship if he so desires. Such a child is as truly a dual citizen as the Japanese child born in the United States. It is only in the Japanese machinery for the divesting of such citizenship that any difficulty exists.

I have stated above that seventy-five percent or more of the nisei are loyal United States citizens. This opinion was formed largely through personal contact with the nisei themselves and their chief organization, the Japanese American Citizens League [JACL]. It was also formed through interviews with many people in government circles, law-enforcement officers, business men, etc., who have dealt with them over a period of many years. There are several conclusive proofs of this statement which can be advanced. These are:

(b) Many of the nisei leaders have voluntarily contributed valuable anti-subversive information to governmental agencies.

(c) The Japanese Consular staff, leaders of the Central Japanese Association, and other who are known to have been sympathetic to the Japanese cause do not trust the nisei.

(d) A great many of the nisei have taken legal steps through the Japanese Consulate and the Government of Japan to officially divest themselves of Japanese citizenship (dual citizenship), even though by so doing they become legally dead in the eyes of the Japanese law, and are no longer eligible to inherit any property which they or their family may hold in Japan.

The United States recognizes these American-born Orientals as citizens, extends the franchise to them, drafts them for military service, forces them to pay taxes, perform jury duty, etc., and extends to them the complete protection afforded by the Constitution and Bill of Rights, and yet at the same time has viewed them with considerable suspicion and distrust. So far as it is known to the writer, no particular effort has been made to develop their loyalty to the United States, other than to permit them to attend public schools. They are segregated by zoning laws, discriminated against in employment, and rebuffed in nearly all their efforts to prove their loyalty to the United States. Yet at the same time, those who grow to the age of about 16 years in the United States and then go to Japan for a few years’ education find themselves viewed with more suspicion and distrust in that country than they ever were in the United States. The majority of them return after a short time thoroughly disillusioned with Japan and more loyal than ever to the United States.

It is submitted that the only practical, permanent solution of this problem is to indoctrinate and absorb these people, accept them as an integral part of the United States population, even though they remain a racial minority, and officially extend to them the rights and privileges of citizenship, as well as demanding of them its duties and obligations.

If such steps are not taken, the field for proselyting and propaganda among them is lost entirely to Japanese interests acting through consulates, consular agents, so-called "cultural societies,” athletic clubs, trade treaty aliens, representatives of steamship and travel agencies, “goodwill" missions, etc. Much can also be accomplished through Buddhist and Shinto priests who, through a quirk in the U. S. immigration laws, may and have entered the country freely, regardless of exclusion laws, as "ministers of religion.” It is well known to the writer that his acquaintance with and encouragement of nisei leaders in their efforts towards Americanization was a matter of considerable concern to the former Japanese Consul at Los Angeles.

It is submitted that the nisei could be accorded a place in the national war effort without risk or danger, and that such a step would go farther than anything else towards committing their loyalty to the United States. Because of their physical characteristics they would be most easily observed, far easier than doubtful citizens of the Caucasian race, such as naturalized Germans or Italians. They would, of course, be subject to the same or more stringent checks as to background than Caucasians before they were employed.

In considering the degree to which the nisei have become Americanized and the factors which have brought this about, the attitude of the issei parents has a great influence. It has been conceded generally that there are a great many issei who are at least passively loyal to the United States. It must be remembered always that the last issei to enter the United States did so in 1924. It should likewise be recognized that American influences have affected these issei, consciously or unconsciously, directly or indirectly, constantly since that time. Furthermore, it must be remembered that one of the chief factors affecting this Americanization of issei has been the children themselves, in the reports they bring back from their school life, their play, or from their associations with white American children.

These factors have worked to a greater or less degree on the individual issei. The real conflict between the two ideologies, American and Japanese, is in the issei, for they have their background of life in Japan and must struggle to reconcile these two very different phases of their lives.

If the above is conceded, it must therefore be conceded that the Americanization of the nisei has proceeded with at least the tacit consent, if not the active cooperation, of many of the Japanese-born parents. In fact, it is such a natural thing that it has proceeded and will proceed to a greater or lesser degree despite the active opposition of the parents. The degree to which the parents oppose it is a measure of the strength of the loyalty to Japan of the parents. That there are factors in America tending to strengthen that loyalty is conceded. These factors are the Japanese associations, the Japanese consular system, and most of all, the fact that the parents cannot become citizens of this country although they may have the status of legal residents. That some of the nisei are more Americanized than others is not so much a measure of the success of an Americanization program as it is a measure of the strength of the opposition to such a program, usually on the part of the parents. Unless there is conscious, active continuous opposition, the child will absorb Americanization as naturally as he breathes.

It is, I think, a Japanese characteristic to have a very great reverence for and thirst for knowledge and education. The teacher is a person of importance in the Japanese mind and the words and teachings of the teacher are greatly respected. Therefore, the fact that the teacher said thus and so not only affects the children but by being reported by the children to the parents affects the parents likewise. Furthermore, I do not believe it can be said that the school influence ceases with the dismissal bell. Quite the contrary. The school influence carries over into the home and to the hours outside the school through such media as school books, school magazines, extracurricular school activities such as games, sports and contests, hygiene, diet, dress, and so on.

The nisei children have always been in the minority in schools and community life, and have naturally and very conscientiously striven to conform to the standards of the majority, which are the American standards. The expression so common in England that a thing "is or is not done" is fully as applicable to the nisei, obtaining to a far greater degree than would be the case with the average Caucasian American.

I think this idea of conformity can best be illustrated by a story told me by Fred Tayama of Los Angeles. In discussing the evacuation program, Fred stated that the greatest concern on the part of his wife and himself was the inevitable loss of Caucasian American teachers and playmates for his children. Fred said, “My parents came over here many years ago. They desired quite earnestly to adapt themselves to the ways and customs and life in this new country. They were poor and had to work very hard for long hours in order to provide a living for themselves and for us children. They were anxious that we attend American schools; that we children who were born here and were citizens of this country should have every opportunity to make our own place in this country. Nevertheless, we suffered somewhat in that our parents could not fully bridge the gap, largely because of language, and were not able to take an effective part in such American activities as the Parent-Teacher Association, consultation with individual teachers, community meetings and projects, and other normal community activities in which the Caucasian American participates.

"We, the nisei, feel that we have bridged that gap. My little girl is 10 years old. She plays the violin in the school orchestra. She has a job in the school library on a volunteer basis. She belongs to a number of school associations. We are members at the Parent-Teacher Association, and freely and frequently consult with our daughter's teacher. As far as we are able to tell, our daughter mingles with her Caucasian schoolmates on terms of absolute equality. She can understand a very little bit of Japanese which she has picked up from her grandmother, but cannot and will not speak the language at all. We have no intention of ever sending her to any language school. We value her association with her teacher and playmates above everything else, and those are the things which we are being asked to give up by this evacuee program. I deeply hope that some method can be worked out whereby contacts and friendships between the two racial groups can be maintained and most of all whereby Caucasian American teachers can be employed on the projects to further the Americanization influence and keep alive American outside contacts.”

I believe that this is a typical sentiment with these people.

It is granted freely that the position of women is far, far higher in America than it is in Japan. This fact is fully as apparent to the issei mother as it is to any other person, probably more so. The issei mother in nearly all cases desires a higher position not only for herself but for her daughters. Even in opposition to the father, she will encourage her daughter to adopt American standards, and encourage her sons to accord women the position they occupy in American life.

Furthermore, coeducation proceeds to a far greater degree in this country than it does in Japan. There the boys and girls are put into separate schools at a very early age and there is very little association between the sexes. Here coeducation proceeds through college. Boys and girls learn to know and understand each other to a degree that is completely impossible in Japan. In this manner, the girls themselves demand and receive from the boys the deferential treatment accorded to American women in general.

This difference is best exemplified by the breakdown on this account of the Japanese marriage system. In Japan, marriages are arranged by family contracts, usually by means of a marriage broker or "go-between.” The parties to the marriage very seldom, if ever, know one another before the marriage. Often, they have not even seen one another before the marriage service. In America this system was among the first Japanese customs to be broken down. The forms still persist to some degree, largely as a sentimental concession to the parents, but in nearly all cases the boys and girls are well acquainted and in love on their own, and they themselves as a rule arrange the formalities of "go-between" and contact between families.

So far has the Japanese custom broken down that if a marriage is attempted on the old system, the children themselves can and often do refuse to have anything to do with it unless and until a genuine acquaintanceship and affection has developed between the two parties. It is quite customary that it the girl decides to refuse, the parents no longer insist.

The difference is also noted in dress. The issei women have universally adopted western costume. The nisei, both boys and girls, despise the Japanese dress since it is confining, uncomfortable, and most of all does not conform to customary American standards. The girls in particular have taken enthusiastically to American customs in the use of such items as cosmetics, makeup, silk stockings, methods and styles of hair dress, and the like. It is true that on certain ceremonial occasions they occasionally resort to the Japanese kimono. This, however, is a sort of fancy dress costume and even on these occasions the American style of hair dress and the use of American cosmetics and makeup still persist. I have never seen in the United States a Japanese girl use the Japanese style of hair dress or the Japanese style of makeup even on the most ceremonial occasions.

Religion has likewise played its part. The Christian religion as practiced in the United States is a powerful influence toward Americanization. The Buddhist religion, being very adaptable, is to a large degree conforming to the American thought and way of life. It has had to in order to persist. It has streamlined itself so that it now includes such American customs as young peoples' associations in which both boys and girls participate; there are Young Men’s and Young Women's Buddhist Associations, modeled on the YMCA and the YWCA. Many other customs and innovations have been introduced so that at the moment the Buddhist religion itself as a religious belief is not contrary to the American way of life. That many of the priests are alien importations who have deliberately used their influence in favor of Japan, and who may have been planted here by the Japanese government for that very purpose, is freely admitted and must always be borne in mind. Also it is conceded that most of the pro-Japanese issei are members of the Buddhist faith and therefore may have been instrumental in the introduction of alien priests. Nevertheless, the tenets of the faith are perfectly acceptable and cannot be classed as un-American.

The effectiveness of religion is best exemplified by the conditions on Terminal Island before the evacuation. Even in that very Japanese community, the Baptist Church was the center of community life. The Sunday School at that church was the social center of all nisei activities.

It conducted cooking and sewing classes; had church suppers, socials, baseball games, picnics and the like, all on the American style. The pastor of that church was himself a nisei educated in the United States and ordained in an American Theological Seminary. There was also attached to the church a Caucasian American missionary who was a member of the Baptist Board of Home Missionaries. The contrast between the activities surrounding the Baptist Church and those surrounding the Buddhist Temple, which was less than a block away, was startling. The Christian Church always had at least five times as many people participating in their activities as did the Temple.

Inquiry has been made concerning the caste system among the Japanese in America. In general, it does not exist, for a very good reason. Practically without exception, all of the issei who came to America came from the same social group. Hence the caste lines were not imported. There did and do exist social distinctions, but these social distinctions as a whole are essentially the same as those in any American community. They are based on business success, degree of education, religion, and so on, the same as in any American community. This complete breakdown of the caste system is best exemplified by the case of Walter Tsukamoto, a very brilliant young nisei attorney from Sacramento, who has been voted the outstanding nisei in the United States and who is admired as a speaker and as a lawyer. Tsukamoto came from the "Eta" class of "untouchables” who are almost pariahs in Japan.

There exists among the nisei a desire to rise above their environment and to separate themselves, if possible, from a purely Japanese community. This was shown to me plainly by two young men from Terminal Island, both college graduates and both young men of considerable ability. One of them asked me point blank what I thought his chances were of getting employment as a machinist in the ship building plants developing in Los Angeles harbor. He stated that he was a college graduate with a degree in engineering; that he was a good machinist with a considerable knowledge and experience in Diesel engines; that in the last few years he had made his living as the engineer of a fishing boat. He stated that he could see no future in his present employment and that as long as he continued living on Terminal Island and engaging in the fishing industry, he would be classed as "just another damn Jap." He thought he saw in the demand for skilled laborers in the ship yards an opportunity to separate himself from this Japanese environment, to do a patriotic service for his country, and to establish himself in a recognized trade or industry. I told him that I thought his chances were very slim, not because of his race, but merely because he belonged to a minority group in the American population of whose loyalty and integrity the people at large were not sure. He replied, "Well, thanks for the answer. It's at least an honest one and nobody can stop me from trying." But he did not get the job.

The other case is somewhat similar. The boy had made and invested a certain amount of money in the fishing industry and had profited thereby. He immediately retired from going to sea and was engaged in furnishing fishing supplies, such as nets, floats, hooks, provisions, and the like. He married the girl or his choice who had gone through high school with him and immediately purchased a lot with a most attractive house in the near town of Lomita, and moved from Terminal Island.

A third case, which to me is quite typical, is that of Harvey Hanamura. Harvey was educated in Los Angeles and was a graduate of the University of California. He likewise was engaged in the fishing industry. In the course of conversation one day he told me that he and his younger brother were the only two members of his family in the United States; that his parents had returned to Japan. He stated that his father had returned reluctantly but from a sense of duty since he, the father, was the eldest son of the eldest son, and as such, was in line for the legal position of "head of the family" in Japan. He had in fact returned in response to the pleas and demands of Harvey's grandfather. Harvey stated that his father in Japan was now growing old and that he in turn was writing Harvey, urging that he return to Japan and take up his duty and legal obligations as “head of the family." I asked Harvey if he intended to do so. He said "Not at all, Mr. Ringle, I have been there. I went over when I was about 18 and took two years of college. I don’t want any more! Furthermore, my wife was born and brought up here and is American and would be utterly miserable in Japan. Again, my son who is now only two was born here. He is the third generation. I intend to do everything I can to bring him up completely and entirely in the American way, and to sever all ties and connections with Japan. I will never see my father or my mother again. It is rather difficult at the moment to resist my father’s pleas, but he will not live many more years and if I can hold out that long the connection will be permanently broken.”

Loyalty is a rather dominant characteristic of these people. Just because of that, loyalties are rather slow in being given, but once conferred are conferred without reservation. I think this hesitancy to confer loyalty accounts for a great deal of the apparent suspicion and unwillingness to accept individual leadership on the part of the Japanese in America. I believe, however, that by and large, the nisei and many of the issei have definitely made up their minds to confer their loyalty on the United States. I think that by and large we are justified in counting on that loyalty.

Another factor which is not commonly realized is that the nisei is not welcome in Japan. He is complete "fish out of water” and no one feels it more keenly than he. In making this statement, I refer to the nisei who grows up in the United States to the age of about 17 or more and who then goes back to Japan either to finish his education or to seek employment. In Japan he is looked upon with far more suspicion than a white person. He is laughed at for his foreign ways. He is called an American spy. In other ways he does not conform and finds himself unable to do so. He cannot live on the Japanese standard of living, on the Japanese diet, or accustom himself to Japanese ways of life. It is my firm belief that the finest way to make a pro-American out of any nisei is to send him back to Japan for one or two years after he is 17 or more. Often a visit of only a few months is sufficient.

This is exemplified by the story of a maid who worked for me. Her parents had taken her back to Japan to a small farming village when she was 16. She was utterly miserable. She did not speak the Japanese language any too well -- which is the case with most nisei. She was forced into Japanese dress which was uncomfortable and in her eyes appeared ridiculous. She was laughed at and talked about and ridiculed by the entire village for her American way of thinking and her American mannerisms. She was called forward, immodest, and fresh. She was so utterly miserable that she finally prevailed upon her parents to allow her to return to the United States alone, which she did.

It may well be asked why the views expressed herein are not more common. This is attributable to the extreme youth of the nisei, and to date, their economic dependence on the issei. This dependence is very real, and has forced many nisei to do things which they would otherwise not have done. For instance, the holding of jobs was sometimes made contingent upon regular contributions by nisei toward the purchase of Japanese war bonds; upon nisei joining some Japanese society, and the like.

Also, the Caucasian Americans of power and influence whose opinions and decisions carry weight are the same people who -- rightly at the time -- brought about the exclusion act, and who therefore see in all Oriental faces, issei and nisei alike, the very alien and incomprehensible type of peasant who was entering the country twenty-five or thirty years ago. The white contemporaries of the nisei, the young people who were their school mates, are not yet in positions of influence in politics or business. Ten to fifteen years from now when both groups have matured, these conditions will no longer obtain, and they will meet on grounds of mutual acquaintance and understanding.

To summarize the above, it is my belief that the Americanization process is a very natural one; that had this war not came along at this time, in another ten or fifteen years there would have been no Japanese problem, for the issei would have passed on, and the nisei taken their place naturally, and without comment or confusion in the American community and national life.

There is no place where the sharp cleavage between the generations is more pronounced than in the field of organizations. Therefore, this section must of necessity be divided into two parts -- issei organizations and nisei organizations.

Issei Groups. The first were very definitely Japanese in character and origin. Possibly the first groupings were the "kenjin kais." These were merely social organizations formed on the basis of places of origin, exactly similar to the "Kansas Club", the "Iowa Club" and others prevalent in California. They held social gatherings, picnics, and the like and no doubt served as clearing houses for news of family and friends and gossip based on the original town, village and prefecture or "ken" in Japan. There were also guild or occupational organizations. Next, certain patriotic organizations made their appearance. These begin to be subversive in character, for they included such groupings as the “Japanese Military Service Men's League"; the "Military Virtue Society"; the "Japanese Navy League"; and a host of others. While the members of most of these groups were probably not anti-American in word, deed, or intent, they were very definitely and strongly pro-Japanese. The organizations served as collection agencies for contributions to the Japanese war funds; purchased Japanese war bonds in large quantities; and contributed money and goods and services to the Japanese troops in the war against China.

All of the organizations were bound together through the Central Japanese Society. This Society was a sort of "holding company" in which all of the lesser groups were share holders and contributors. The Central Japanese Society was headed in Los Angeles by a man named Gongoro Nakamura, who was looked upon generally as the most dangerous Japanese in Southern California because of the power he wielded and because of his close association with the Japanese consulate. He was placed in custodial detention along with many other leaders on the seventh of December. It should be noted, however, that this Central Japanese Association served a very useful purpose for the Japanese alien during the twenty years preceding the war. The Japanese, after all, was an alien and a citizen of Japan. His status in the United States was somewhat ambiguous. The open purpose, rather well carried out, was to look after and in so far as possible, protect the interests of the alien Japanese resident in this country. That it also served to keep alive some of his interests and ties with the home country was inevitable. It was through this organization that the language schools were fostered; delegates were sent back to Japan for specific purposes, such as attending the celebration of the 2600th anniversary of the founding of the Japanese Empire in 1940. It was through this organization that the "Japanese Overseas Compatriots Society" was founded in Tokyo at that time.

Nisei Groups. The nisei, on the other hand, were not too susceptible to this sort of organization. They had no background of a common home town or home state in Japan. They did not understand too much of the language or the Japanese ideology. They were rather impatient with the language schools, but attended at the command of their parents. The nisei grouped themselves into organizations much the same as any group of white Americans, on religious, social, occupational, or other congenial groupings. These organizations were as mutually distrustful of one another as any similar white organizations would be. To illustrate this point, some months ago a group of JACL members went to the mayor of Los Angeles to discuss the entire Japanese situation with him. On learning of their organization and the number and type of persons represented, he said "You people are not truly representative of the group as a whole. Go get yourselves a group or committee which is truly representative and then we can talk."

At first blush this seems to make sense. The Japanese called a mass meeting and attempted to organize a group known as the "United Citizens Federation.” At the organization meeting were representatives of same eighteen organizations, such as the Produce Workers Association, the JACL, the Buddhist Church, the Nisei Merchants Association, various agricultural organizations, the Catholic church group, the YMCA and YWCA, the Boy Scouts, various women’s clubs, etc. It was as heterogeneous a group as would result if an attempt were made to organize the Masonic lodge, the Knights of Columbus, the Rotary Club, the Farmers Grange, the WCTU, the Seventh Day Adventists, and the CIO boiler-makers union. It fell to pieces immediately. The groups had nothing in common whatever except a common racial background and that is not sufficient to hold these people together.

It is my opinion that in this very disunity lies the greatest hope of these people as well as the greatest hope and expectation of the country for them.

The language schools were started originally so that the children might become familiar with the language of their parents and relatives; so that the children might have some channel for tapping the culture, history, art, literature, etc. of Japan, as well as creating opportunities for employment in foreign trade or other fields in which knowledge of an Oriental language would be helpful.

Of course, there were certain disadvantages. Japanese ideology was bound to creep in and it is freely admitted that the issei did very little to discourage it. In many cases they would seek such teaching in a deliberate effort to keep the child essentially Japanese. It is believed that those with this motive were in the minority, however.

Another factor contributing to the growth of language schools was the refusal for many years of school boards and others to allow the teaching of the Japanese language in the public schools. Had the other course been taken by the American authorities -- had they allowed or encouraged the teaching of the language in the public schools under proper supervision as is done with European languages -- and the private unsupervised schools were legally forbidden, both the country and the Japanese themselves would be far better off today. Language after all is merely language and a vehicle for the expression or transmission of thought. The Japanese language itself could have been the medium for the teaching of American ideals.

Even so, it is a known fact that only about 20 per cent of the nisei, and less than 1 per cent of the sansei were students in these schools.

The Japanese language papers served not so much as a vehicle for the spreading of general world news, although they did fulfill that function, as media for spreading news of a more personal nature. The community, particularly the nisei community, read a variety of other papers as well. Of course, the language press served primarily the older issei whose knowledge of the English language was limited, and the kibei who likewise had difficulty with English. It is to be noted that the vernacular papers themselves were commonly printed in both languages, and the tendency in recent years as the issei became fewer and the nisei more numerous was toward more and more English and less and less Japanese. The English sections of the vernacular papers carried news of and pertaining to the nisei as a group rather than general information.

I have no first-hand information as to the extent or amount of subsidies paid by the Imperial Japanese Government to Japanese language newspapers in this country. I am even unable to say which newspapers, if any, received such subsidies although it seems logical to suppose that some of them may have. If exact information on this subject is important to the work of the Authority, I believe that an inquiry either to the Office of Naval Intelligence or to the Federal Bureau of Investigation might be worthwhile.

I do have same knowledge, however, of the setup and operation of the Japanese language press. In most cases, these papers operated with two separate and distinct staffs -- one for the English section and the other for the Japanese section. Usually there was no connection between these two staffs other than a common owner or managing editor.

PROTECTION OF THE LOYAL EVACUEES

Protecting the loyal Japanese from disloyal influences can, in my opinion, best be achieved by separating evacuees into two groups in accordance with the two basic objectives governing the entire relocation program. These objectives, as I understand them, are first and foremost, to protect the country from disloyal acts, and second, to protect the evacuees from thoughtless or misguided acts of violence on the part of Caucasian Americans. If two different types of relocation centers are set up, I believe that the question will be solved.

On the basis of logic and reason, two classes of persons may be considered potentially dangerous to the internal peace and security of the United States and to its war effort. The first are those aliens born in Japan who have retained sufficient of their Japanese ideology and patriotism so that they are in spirit loyal citizens of the Japanese Empire. The second -- who may well be children of the first -- are those American citizens of Japanese ancestry who have spent sufficient time during their formative years in Japan so that they are in all probability citizens of the Japanese Empire in spirit despite their legal American citizenship.

It is my belief that this group -- the kibei -- includes those persons most dangerous to the peace and security of the United States. It seems logical to assume that any child of Japanese parents, who was returned to Japan at an early age, grew up there, studied in Japanese schools, possibly did military service in the Japanese army or navy, and then as an adult returned to the United States, is at heart a loyal citizen of Japan, and may very probably have been deliberately planted by the Japanese government.

Now, at what ages are persons susceptible to such indoctrination? To be on the safe side, the writer has considered such years to be from the age of thirteen to the age of twenty. How many years are necessary for such indoctrination? Again to err on the safe side, this writer has considered three years to be the minimum time.

It is my belief that the total number of American citizens of Japanese ancestry who can be classed as kibei is between eight and nine thousand. The identity of the kibei can be readily ascertained from United States government reports.

It is believed that this class once segregated should hold the status of enemy internees. They should be physically separated from the balance of the Japanese and Japanese descendant population; should be guarded both for the protection of the United States and for their own physical protection; should not be allowed employment in private industry or membership in the War Relocation Work Corps; and at the first opportunity or at the conclusion of the present war be deported to Japan, and their status as legal residents of the United States or as citizens of the United States canceled.

As concrete suggestions of the way in which such a segregation could be determined and effectively carried out, the following is submitted:

2. By a process of registration within assembly and relocation centers, determine the identity, together with the identity of parents, spouses and dependents, of all American citizens of Japanese ancestry who have spent three years or more in Japan since the age of thirteen. If it seems desirable or necessary, these lists may be checked against the records of the Federal investigative services including the records kept by the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization. This second category will include those citizens of Japanese ancestry who, in all probability, may be considered as potentially dangerous. Parents or guardians of such persons are included for the reason that it was these parents or guardians who sent the children to Japan to be so educated and so indoctrinated that they are to all intentions and purposes citizens of Japan and subjects of the Emperor thereof.

It is in this category that the greatest exercise of judgment must be used. A reversal of the commonly accepted legal procedure must be exercised, for the best interests of the United States, with persons considered guilty unless proven innocent. It is suggested that at each assembly or relocation center, boards for the review of such cases be set up. These boards should consist of representatives of the military service, of the Department of Justice, and of the War Relocation Authority. These boards should in no way be confused with or identified with "loyalty boards" but should be set up for the express purpose of deciding on the basis of logic and reason, and in view of the circumstances in each case, whether or not the individual is to be considered in the class of potentially dangerous. It is further suggested that these boards can be guided by the following principles:

(b) Giving due consideration to the predominant position held by the male in Japanese society, the classification of the male should be the primary deciding factor. By this is meant that if a kibei male is married to a nisei female, the family should in all probability be classified as kibei. If the reverse is true and a kibei female is the wife of a nisei male, the family should in all probability be considered nisei and therefore not dangerous.

(c) Children below the age of seventeen shall take the classification of the parent or guardian. Children seventeen years of age or above shall be judged on their own merits and given the choice as to whether or not they will accompany the parent or guardian.