|

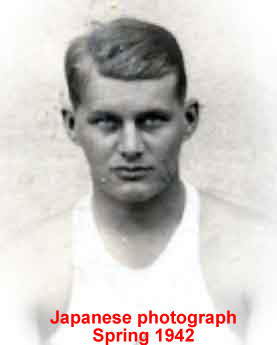

Carroll D. "Barney"

Barnett PFC , USMC, Sumay Marine Detachment, Guam |

Main Index Page Main Zentsuji Page About Us

|

January 7, 1921 - December 4, 2001 May God embrace him. May he rest in peace.

|

|

|

The following interview was conducted on

10 February 2000 and 26 October 2000. We all knew about the methods of the Japanese…they would take no prisoners. The news about the Rape of Nanking and other Japanese atrocities were known to everyone. We simply decided to have a good time until the war started. Governor McMillan had tried to get us all evacuated but was told the ship, the SS Harrison,(2) and its current load of passengers from China and the Philippines, was too valuable to risk by attempting to gather the men and nurses on Guam. We were simply deserted and sacrificed. After the war and shortly after I returned home to my home town of Waukee, (3) I was visited by two men from the FBI. They came to my home and I was told, in no uncertain terms, to keep quiet about my knowledge that we knew the attack was coming and the events leading up to the 8th of December. If I refused to keep quiet, I would be immediately given a courts marshal and put in prison.(4) The implication was that I kept my mouth shut. When friends asked what the FBI wanted with me, I simply said I'm not allowed to speak about what happened." Had the Japanese known their attack on Pearl Harbor was to be so successful, I'm sure they would have capitalized on the destruction of the fleet and seized Hawaii. While we were in prison, many sentries and civilians with whom we made contact expressed the same conclusions. Still, most recognized they could not seize the mainland because they understood every American owned a gun. The right to own a gun was unique to the Japanese at that time. They constantly made reference to the fact that they would have to negotiate a peace sooner or later. On 8 December, I was just leaving the galley, heading for the Marine Radio Station, when the first bombing raid started. A bomb hit next to the radio station and killed a guy inside. I think he name was Anderson. We started to run across the field when the first bomb exploded. I remember seeing "Babbs" (5) get hit and his leg was torn to shreds. From the first attack on, the Marines at Sumay didn't do a damn thing. Our weapons were useless relics, many of us were unarmed and Col. McNulty was absolutely useless. No one had much respect for him. He was simply sent to Guam to finish out his years until he could retire. I was assigned to a transport section, given a truck and told to wait at a particular point away from the base. The morning of the first attack was pure chaos and confusion. After the attack, McNulty told me to take the truck, a twelve foot, stake body, International K7, and wait near the gravel pit, about three miles southeast of Sumay. Told to, "stay out of the way", the only person I saw was Dewey Danielson, (6) who checked up on me and brought me a couple sandwiches. On the day of the invasion, I was in my truck and was told the island had surrendered and we were to march into the barracks and surrender. As some 35 to 40 men began to assemble, I decided to hide out and ducked into the bushes. I felt certain the Japs were going to kill all of us. Later that morning, I began driving the truck away from camp with four other Marines aboard, all of us intent on hiding out up on Mt. Almagosa until the American fleet arrived in a few weeks. As we headed uphill, from both sides of the road about fifty Jap soldiers suddenly stood up and aimed their rifles at us. This was one ambush we were not going to get out of so we stopped and raised our hands. De Saulniers (7) and the other three men walked back while I was forced to drive the truck, loaded to the gunwales with Jap soldiers. Two guards were in the front seat with me and two others hung from the running boards on each side. With the back crammed with Jap soldiers, I started to think that, since I was soon to die, I'd kill as many as possible. About a mile ahead lay a curve and I would drive over the cliff. As I started to shift gears, the Jap guard next to me stopped my hand, indicating I was not to shift out of first gear. I could never get up speed to kill the bastards so we arrived in camp some twenty minutes later. They marched us back to the Marine barracks, stripped us of our clothes, watches, wallets, rings, pens and anything of value. We sat outside, stark naked on the grass, while they looted the barracks. Under the burning sun, we simply sat in a circle, praying for something to happen to end the tension. The total lack of water simply added to the terror. Just before dusk, we were given some clothes, taken inside and spent the night in the pool room. Just before dawn, we were fed a rice ball about the size of a small chicken egg. Little did I know this would be my last food for weeks. As the sun rose, the five of us were taken across the golf course and lined up against the fence by the Pan Am station. Two machine guns and a firing squad was arrayed in front of us. The officer shouted a sequence of orders that we all assumed meant to take aim and fire. Instead of firing on the command, they charged towards us, bayonets fixed and screaming at the top of their lungs. Just as they came within a few feet, they turned their rifles sideways and struck each of us. We were sent sprawling against the fence and onto the ground. They repeated this sadistic ritual three times. When they prepared again for the fourth time, a new set of orders seemed to have been shouted by the officer. The soldiers removed clips of ammunition from a box on their belts and loaded their rifles. Now we knew the end was coming. Just then, a soldier came running across the field, spoke briefly with the officer and an order was given to stand down. The officer departed with the runner but returned some twenty minutes later. He now addressed us as we stood at attention. "We have decided not to kill you if you will be slaves. If you agree, your lives will be spared. If you do not agree, you will die now." We all nodded our agreement. The officer continued, "If you are ever unhappy, we will gladly complete at any time." The Japs loaded us aboard a truck and drove into Agaña. At the city jail, we were placed in a windowless cell, a drain hole in the center for relieving ourselves. With a war merely two days old, we felt horribly alone, believing that all others had been murdered. All we could see were the Jap jailers and none cared if we lived or died. Next to the jail was the island's cold storage unit. The Japs systematically looted all the contents. When they discovered some canned peaches, we were told to "sample a half peach" to see if it may be poisoned. Not dying from my half peach, the rest were removed by the Japs. All that remained was twenty one cases of butter, eighteen inch cubes weighing about 50 pounds each. The Japs hauled them into our cell and stacked them along the wall. A tropical jail cell is not a refrigerator and within hours, melting butter covered the floor, seeping into every crevice and saturating our clothes. Within a few days, every part of our bodies was covered with the rancid, slimy oil. The smell became unbearable yet the butter was all we were to eat until the night before we left Guam. To this day in my mind, the rancid smell of that butter can be recreated in an instant. The oily ooze, covering the floor, made sleep a luxury. The gentle slope to the center became a slippery slope that seemed vertical. On the 6th of January, J.H. Lyles and J.H. "Little" Jones, (8) were shoved into our cell. They were the first fellow Americans we had seen since the invasion. Apparently, the Japanese had announced they were taking the prisoners to Japan. Word had spread that any Americans left on the island would be killed on sight so Lyles and Jones had come in from the boonies and surrendered. They were the first indication I had that any others had survived the invasion. On the afternoon of the 8th, the seven of use were taken to the cathedral. I was so weakened by starvation that I had to be carried inside. It was exhilarating to discover that all these men were alive! I was so sure that we were the sole survivors. That evening, I was given a tiny potato, my first food in almost thirty days. On the 10th, I was trucked to Piti and carried aboard the ship. The stink of rancid butter was not much different than most others when it came to fouling the air. I was placed against the hold, almost unable to move. When a bucket of worm ridden rice was lowered into the hold, it was almost every man for himself. I hollered and finally, someone passed me a small portion of rice. When one man pushed his rice away, saying, "I won't eat this bug ridden garbage," I again hollered and got his share. In Zentsuji, I was sold into slavery along with thirty to forty other men to work for a railroad company. Every day we would load and unload box cars in Takamatsu. At night, we would be returned to our quarters in Zentsuji. 1. Chief of Staff: Prewar Plans and Preparations, p 98, Exploratory Studies, 25 Jan 39, Col. Frank S. Clark, War Plans Department, "If the American government…had so considered, the Japanese denunciation of the Washington Treaties [Naval Limitations] would have been followed by the impregnable fortification and garrisoning of the Philippines and Guam…Whether right or wrong, they have successively undermined the possibility of successful defense…of these possessions." Back 2. As a result of a continuous string of "war warnings", Governor McMillan (Captain, USN) ordered the military and civilian dependents, along with dependent children, sent back to the States beginning in June of 1941. On 17 October 41, the last of the dependents departed aboard the military transport MTS Henderson, except Mrs. Ruby Hellmers, the pregnant wife of John Anthony Hellmers, Chief Commissary Steward, Admin. Staff, U.S. Navy. The SS Harrison (American President Lines) was conscripted by the military as a transport. It passed through Manila at the end of November. Back 3. Waukee, 10 miles west of Des Moines, Iowa, was a small town of about 300 people before the war. Today, it is simply a part of the urban sprawl of Des Moines. Back 4. Chief of Staff: Prewar Plans and Preparations, p 353, As late as 31 Jul 41, Chief of Staff Marshall explicitly directed the War Plans Department "To avoid major military and naval commitments to the Far East at this time." This was classified as Top Secret. Back 5. James W. Babb, Pfc, USMC. His leg was amputated. Back 6. Danielson, Dewey C., FM1c, Sumay Back 7. Armand C. De Saulniers, PFC, USMC, Sumay Back 8. Sgt. John H. Lyles and PFC John H. Jones, USMC, Sumay Back |

||

Barney & Dorothy

Barney & Dorothy