TESTIMONY OF CLAUDE DAVIS HOWES

Re-publication prohibited without written permission from:

Don Matthews

1050 NE 239th Place

Wood Village, Oregon 97060

(503) 669-0430

american.survival@verizon.net

During the last of 1940, I was out of work and heard The Dredge Columbia, which was owned by The Port of Portland, was going to Tongue Point near Astoria to dredge a naval base.

I contacted the chief engineer, Stanley Carlson, whom I had known for several years. He gave me a job as fireman. Everything was working fine at Tongue Point. On our day off we would either go home to Portland or go to Astoria and fill up on beer. Our cook had a hog ranch up the highway a few miles -- he couldn't make hotcake worth a damn. He took the chief some hot cakes one morning. The chief asked him who told him he could cook? "Why those cakes are tougher than a mother-in-law's heart."

Jan. or Feb. 1941

Some lame duck came aboard the dredge. We found out later he was Mr. Hanscomb from the Pacific Naval Air Base Contractors. He wanted the dredge for a government project at Wake Island. Mr. Hanscomb made a deal with the Port of Portland to rent the dredge. Of course he had to have a crew so he started on the chief first. I think he offered the chief $300.00 per month, but Tiny (we all called him Tiny, he only weighed 290 lbs. and wore No. 19 shirt) held out for more money. I think they settled for $400.00 and bonus. Now Tiny wanted some of us to go along with him as we were experienced and he would not have to break in new men.

We finished the job at Tongue Point and the dredge was towed to the Port of Portland Dry Dock for overhauling. We changed the digger engine, put in a new pump and went over everything from stem to stern. The chief had quite a time getting his crew as we had to pass a physical examination. Tom Gillen, Frank Follett and Herman Britt were the engineers. George Dowling, Whitey Campbell and myself were the firemen elected to ride the dredge from Portland to Wake. There were 12 of us in all, engineers, firemen and deck hands.

The dredge was planked on the outside with double 3 in. plank to ward off the heavy waves and we had plenty of them. We pulled out of the Associated Oil dock April 25, '41, at 5 A.M., towed by the steamer Portland and the government tug, Seminole. The steamer Portland left us at Astoria. I don't remember crossing the bar, as someone was passing around a bottle about that time. Here we were out in the ocean bouncing around like a cork. We had to keep steam in case the dredge took water.

At night, the men that were not on shift would gather in the lever room where we had a two-way radio, and we would get our location from the Seminole. Everybody brought along a few bottles of seasick medicine -- of course, we were all seasick. I know Gillen and Tiny had three cases. The Seminole was just a little too light for the dredge. We were all over the ocean, first to the port, and then to the starboard. It took us 16 days from Portland to Honolulu. Were we glad to see land again. I know we landed in Honolulu on Mother's Day as we all sent a message home.

We layed in Honolulu 9 days as one of our light engines went haywire on the way. We all had a chance to see that beautiful beach at Waikiki. I didn't see anything beautiful about it, if you walk on the beach the coral cuts your feet. Of course, the water is awful warm and the weather is ideal, but I think we have a lot nicer beaches here in Oregon. One thing that did interest me was the tropical birds in the park at Waikiki. I had often seen pictures of them in magazines and they really are beautiful.

We pulled out of Honolulu May 21, '41, the Seminole still towing us. We were out 4 days when the tug got orders to turn back towards Honolulu. Nobody knew why. We bounced along for a couple of days when we meet a tug by the name Viro. The Seminole just cut loose and left us out there rolling around. The Viro had quite a time getting a line on us, after she had shot three times, we finally got one.

The Viro was an awful small tug. It couldn't keep the cable tight

and did we swing. Part of the time we were alongside the tug. The Viro

towed us for 3 days but could make no headway.

(POEM)

Finally the oil tanker Kenawa came to our rescue and we had to bounce

around again for at least an hour. The Kenawa made good time, about

8 knots. We pulled in to Wake Island June 6, '41. If there ever was a deserted

place, Wake was it -- nothing there but birds, rats and hermit crabs. The

highest wave on Island only 15 ft. above water. It took some time to get

the dredge stripped and ready for work.

Wake Island is shaped like a horseshoe. There are three islands in all -- Wake, Peal, and Wilks. This forms a lagoon in the center.

Aerial mosaic of Wake Island, December 3, 1941

Japanese air raid on Midway Island, June 4, 1942

Our job was to dredge out this lagoon for seaplanes. This lagoon was very

shallow and full of coral, and it was really very hard on the old tub. The

Columbia was not built for this kind of material. They had to use tons of

powder on this coral in order for the dredge to suck it up. The blasting

loosened several tubes in the boiler. Everybody was going to quit -- the

dredge was broke down half of the time. Some of the men only stayed a couple

of months, and they were smart. The chief planned on pulling stakes when

his 9 months were up, so we agreed to stay with him. Whitey Campbell and

Herman Britt only stayed a couple of months. I don't know if they smelt a

mouse or not, but before the year was up we all wished we had never seen

Wake Island.

(POEM)

We had to get our supplies from Honolulu. Every ship that came in would bring

a bunch of new men, and there was always a gang going back.

On Dec. 8 or the 7th here in God's country, Mr. Teeters, the Superintendent for the P.N.A.B. Contractors, came aboard the dredge about 10:30 A.M. and told us war had been declared, that the Japs had hit Honolulu, for us to go ashore. We got our personal things together and by this time it was noon. We thought we had better eat as dinner was ready. Just about this time we heard planes. We were expecting some American planes in and thought nothing of it, until someone said the island was on fire. The planes came back over the dredge and we could see that rising sun on the wings. Oh my God, what a feeling -- I thought our goose was cooked. Twenty Jap bombers (2 engine jobs) were bombing and machine-gunning the island. They got seven of our planes on the ground the first day -- we only had 12 in all. We also lost about 30 men and several were wounded. Pan Air Hotel and installations was wiped out killing several of their employees, which were mostly Guam boys. The clipper which was laying at the dock during the bombing escaped without a scratch, and the personnel took off for Honolulu and left us holding the sack. Dan Teeters was the only one that stayed by us, or at least he was the only one that did anything for us after the surrender. Mr. Teeters acted as interpreter for us.

Well, we all left the dredge and went ashore. Nobody knew where to go or what to do as there was no dugout or protection from the bombing. The dredge crew split up , but as I had known the chief and Gillen for a number of years, I thought I would stick with them. Tiny suggested that we get away from the buildings and, as he was our boss on the dredge, some of us decided this would be a good idea. Now our gang consisted of four engineers, two firemen, one blacksmith, and one electric welder.

Engineers: Stanley Carlson, Thomas Gillen, William Harvey and Frank Follett.

Firemen: George Dowling, myself C. D. Howes

Blacksmith: Owen Thomas

Welder: Johnson

The first night we did not have anything to dig with so we just slept under the sky.

Dec. 9, '41

We decided we had better dig in, and believe me, that coral is tough digging. Johnson and I decided to hole up together. We finally got a hole about two feet deep and covered it with mattresses which we got from camp. Tiny and Gillen holed up together, of course their hole had to be a little bigger. Pop Thomas made a hole by himself. Harvey never did get in a hole, he just layed out under the brush and watched them come over. Follett had the deepest hole of all. Whenever he heard a plane, he would dive in head first, and his head, which was kind of scarce of padding, sure was skinned up.

12/9/41

Here they come again, with only three of our planes in commission. At 12:00

noon there were 16 Jap bombers, came over at about 10,000 ft. Lt.

Liener and Capt. Elrod met them coming over and shot down one.

Three Marines were reported missing and they hit the hospital at Camp 2 full

of patients which was wiped out. Joe Troy, one of the dredge men was

wounded as he was helping out in the Hospital. After each raid we would pack

a few more rocks and put on our dugout. Tiny and Gillen put so many on theirs,

it caved in. Pop Thomas stood that bombing better than I expected as he was

70 years old.

Excellent site on the Marines defense of Wake, |

Dec. 10

At 10:20 A.M. another raid of 18 bombers came over at about 16,000 ft. They split and some of them came back over Camp 2, doing considerable damage. Capt. Elrod brought down 2 of them and our A.A. guns reported two smoking.

There were only 400 Marines on Wake and about 1,100 contractor men. We could not all man the guns as they did not have enough. I think everybody did their bit. We would go out at night and move the guns and ammunition to new positions. Some of us stood guard and others filled sandbags. Some of the contractor men were World War No. 1 vets, and this was right down their alley.

Dec. 11

They came prepared to take the island -- with 2 heavy cruisers, 5 destroyers, and 2 transports, they began shelling the island. Thank God we were out in the brush for they really did mess things up. One of the bombs landed a good 100 ft. from our dugout. If you don't think that is hard on the nerves, you want to try it sometime. We managed to get 3 of our fighters in the air with two 100 lb. bombs a piece.

Capt. Elrod, Freuler, and Capt. Tharin bombed and sank 1 cruiser and 2 destroyers. The 5-in. guns reported good hits on the other cruiser and a transport. It was later reported that our subs sank all but one destroyer. Lt. Lieber reported that he bombed and machine-gunned a Jap sub. The Major went later and said that there was oil on the water. At 9:30, 17 bombers came over at about 20,000 ft. Lt. Kenney and Lt. Davidson got 2 of them. They did not come over at the same time everyday. But Capt. Elrod was usually there to meet them.

My partner Johnson moved out on me. Here I was alone in our dugout listening to those bombs, wondering what was coming next. I heard someone calling me. Here was Dowling shaking like a leaf, so he crawled in with me. "They're shelling the island," he told me, just as if I didn't know it. Dowling said, "I'm going up to the tunnel," so I was left alone again. Now the tunnel was a shaft under the aggregating plant which was covered with about 20 ft. of gravel, so it made a pretty good dugout.

Dec. 12

About 5:15, one 4 engine patrol bomber came over and dropped a few bombs with little damage. Capt. Tharin was in the air and machine-gunned him full of holes; reported engine smoking.

Dec. 13

Maybe they thought the 13th was unlucky so they did not show up. Thank God they gave us a rest. We had very little food, only canned tuna, and catsup. We did manage to get a loaf of bread which I stole from a cache. Pop Thomas went out looking for something to eat and came back with a 5-gallon can of cookies. Did those taste good.

Dec. 14, 3:40 A.M.

One Jap patrol bomber dropped several bombs on the island but not much damage done. They came back at 11:30 A.M. 37 bombers came over at 20,000 ft. and hit the Marine camp on the south beach. Little damage done, otherwise.

Dec. 15

At 8 A.M., 4 Jap patrol planes bombed the island with very little damage.

Dec. 16, 11:40 P.M.

27 Jap bombers came over and hit Camp No. 2 fairly hard. They also bombed Camp No. 1 but very little damage.

Dec. 17

They gave us another rest, no bombing.

Dec. 18 11:30 A.M.

27 Jap bombers attacked our AA positions but very little damage. Two Jap planes shot down.

Dec. 19 11:35 A.M.

36 Jap bombers in two flights came over at 24,000 ft. Our AA shot down four of them.

Dec. 20

U.S.P.B.Y. came in bringing orders from Honolulu, but did not stay long. At 2:30 P.M., 27Jap bombers came over at 19,000 ft. Bombed Camp 2 hitting it pretty hard. They also bombed Peal Island and hit our AA position, damaging several buildings on Peal; none killed. Some ammunition hit.

Dec. 21 9:40 A.M.

Several Jap fighters came over, most bombing bad, very little damage. Our plane (as I think we only had one left) was unable to locate the carrier. They came back at 12:25 A.M., 33 bombers came in from the West, bombed Peal Island. Sgt. Wright was killed, 4 wounded on the range finder. We went out at night and moved the guns into coast defense position as it was getting pretty hot.

Dec. 22 12:45 to 10:05

We were heavily bombed.

Dec. 23

They came back with several ships. We were heavily shelled and bombed. Japs began landing at 3:00 A.M. and did we mow them down. The surrender took place at 8:00 A.M.

Japanese lost: 27 planes, 3 fortresses, 1 transport, 6 destroyers, 3 cruisers. Killed: 5,000 men.

American lost: 12 planes, 37 civilian contractor employees, 10 Pan American employees and 49 Marines. Killed: 96 men.

As I said before, our dugout was some distance from camp. We did not know they had taken the island. The night of Dec. 23, Tiny, Harvey and myself were going to camp to get some water. We had to walk up the beach some distance before we could get out on the main road. Just as we came to the aggregating plant, we heard Japs talking. Tiny and Harvey, who had been on ships before, told me to run. We started for the tunnel and I got tangled up in some wire. I thought I was a goner, but I finally got free. We made it to the tunnel which was about 100 ft. long. Tiny and Harvey were in the lead and I had quite a time keeping up with them. When we reached the other end, I sat down to rest. When I got my wind, I asked them if they could see any Japs as they were near the door. They did not answer. I moved over closer to the door and discovered they had left me. I did not know what to do. I thought the Japs would get me for sure. I watched the road and listened to make sure there were no Japs around. Then I made a run for the brush. When I got back to the dugout, the gang was killing the last bottle the chief had been saving for Xmas. They thought the Japs had caught me as I did not keep up with them. We decided to lay low and surrender the next morning.

Dec. 24

Tiny, Harvey, Gillen, Pop Thomas and myself packed and started up the road to surrender. We met two Japs on bicycles. They asked us the time. Gillen and Pop Thomas pulled their watches out and the Japs took them. Pop Thomas' watch was very expensive. It had a locomotive on the back with a diamond for a headlight. These two Nips showed us where to surrender. We were allowed to keep the clothes we had on. They searched us, took our suitcases and slapped our faces. Tiny was very much taller than the Japs and they could hardly reach to slap him.

We were loaded in a truck and taken to the airport where the rest of the men were. Some of the men did not have any clothes on, some had only shorts. They told us that the Japs had taken their clothes. If they had a pair of shorts, they were allowed to keep them. They took their American money, tore it up and threw it in the ditch. Then they were marched to the airport. Everybody was kind of shaky as we had heard the Japs did not take any prisoners. We were made to sleep without any covers. Although it was very warm on Wake, the nights were cool.

Dec. 25

Our superintendent, Dan Teeters, and Tommy got some clothes for the men. Our 1941 Xmas dinner consisted of bread and water. The cans they brought the water in had been used for gasoline, so you can imagine how it tasted. Xmas night we were marched to camp, which was about two miles, and were assigned to barracks. While marching to the barracks, I noticed two American flags on the road where the Japs had thrown them. We were unable to pick them up, for if we had, God knows what they would of did to us. The men had to walk on them, and it really hurt me to see our flag in the mud, which to my knowledge had never been there before.

They stood guard over us with machine guns. I think we had them out-numbered as they lost most of their men taking the island. The contractor men were not allowed to take firearms to the island, so consequently we had nothing to defend ourselves with.

The next day, Dec. 26, we were taken out on details to find food which we had hid out in the brush. We were always under guard. One of the Jap officers by the name of Katsumi, who used to be an importer in Chicago, went along with the detail. He pulled his gun on several of the men when they would try to eat some of the food. We had to work every day, digging dugouts, putting up barbwire, building pillboxes, and working on the airport.

Jan. 12, '42

The Marines and some of the contractor men were taken away. U.S. planes came over the island about once a week to look things over. The Japs tried to get them but they were out of range. The Japs had damaged one of their planes landing in the lagoon and had lifted it on a barge for repairs.

Feb. 24

U.S. planes came over and made a direct hit on the damaged plane. They also hit the dredge and burnt the top deck which was wood constructed. Although American planes were still in the vicinity, Katsumi took a detail of men to the dredge to put out the fire. The contractors had provided no dugouts or shelter from the bombings. This was one of the first things the Japs did after taking the island.

American ships shelled the island very heavy from the sea. We found several of the shells including two that hit the dredge and found that they were dummies. The Japs said, "American ammunition no good." They intended to finish the dredging but could not furnish the oil to run the dredge.

Feb. 26

I was working on the paint gang. We were painting on the radio station. One of the Nips that could speak a little English came running out hollering "American hay-tie [heitai]" (which means "American soldier"). We found out later that two flyers off the Enterprise had swam ashore. They were put in the guardhouse and we did not get to talk to them. Tommy the Chinese boy was working in the mess hall and he was detailed to take their food to them. They were in the guardhouse about four days, then they were blindfolded and taken away, nobody knew where to.

Two of the contractor men, Fred J. Stevens and Logan Kay, stayed out in the brush 77 days after surrender. They lived on bird eggs and what they could go out at night and find. One of our men, Julius Hoffmeister, broke into a warehouse and stole some alcohol and cigarettes. The Japs caught him in the act. Stealing is one of the worst things you can do in Japan. On May 10 '42, they blindfolded and had him kneel down beside a hole they had dug. One of the Jap officers cut off his head with a sword and the body fell in the hole. All the American foremen were made to witness the execution.

Two of our men that worked on the dredge, Elmer Mackie of Portland, Oregon, and Don Sullivan of Long View, Wash., left the island at night in a small boat. The Japs told us about a month later they had located them and killed them.

June 1942

They took some more of the contractor men away. We found out later that they were taken to China.

Sept 30

My gang left the island, 265 of us. We were loaded on a ship with double decks. I happened to be in the lower deck where it was very hot. At night we would take turns fanning each other so we could get some sleep. We were allowed to go on top each day for a short period to get fresh air. Several of the men passed out on the trip it was so hot.

We arrived at Yokohama Oct. 11 '42. Had to wait several hours in the station for our trains. Some Nip that could talk pretty good English sure filled us full of bull. He told us we were going to work on a farm 4 hrs. a day and would be allowed to go to the picture shows.

We were loaded on the train and taken to SHIMONOSEKI. Here we had to wait for a boat, so we were taken upstairs in a building where we were allowed to rest. This Nip that could talk English took up a collection of Japanese money, which some of the men collected on Wake, and went out and bought cigarettes. We had to wait here several hrs.

Finally we were marched to the boat and taken to the island of Kyushu, then by train to Sasebo. We were marched through town about 3 A.M. so the Jap civilians could see us, as I think we were the first prisoners taken to Sasebo. At the edge of town, we were loaded in trucks and taken to Camp 18. We were given blankets which were full of fleas and lice and nothing to sleep on but the hard floor. We thought maybe we would get a little rest as we were very tired after our trip on that hot boat. But the next day we were put to work on a big concrete dam.

This camp was under the Navy, the camp commander a sergeant by the name of EGAWA, who was very cruel and gave us several beatings. The men were made up in gangs of twenty men to a gang. Each gang had a Nip boss and they all carried a club. If you could not understand them or do what they told you, they would beat you. One of our men, George Dillon, was working under a Nip we called Grandma. Grandma would pick on George every day. One day Grandma got too close and George let him have it with his shovel. Of course, George was put in the guardhouse, which was very small, hardly room enough to lay down. He had a trial and was supposed to of been freed. They took him away, nobody knows what became of him. [See Edward White's affidavit for description of this incident.]

This EGAWA's motto was "one man bad, all men bad," so the whole camp got

a beating. We were made to stand with our hands over our heads while the

Nip beat us. If you were knocked down, the Nip would kick you and pull your

hair. When you got up, he would beat you again. Oreal Johnson from

Idaho was layed up several days from being beat. We always knew when someone

was going to get beat as the Jap guard would say "Bow lo" [bo wo] which meant

beating. If they said "Bow to high que," [bo wo haikyu] that meant everybody

got beat.

Granddad took a few things home with him from the war. Although never a racist or prejudiced man, he seldom had a kind word for the "Nips". I remember a quiet and gentle man who always could comfort me just by offering his knee to sit on. As a boy, I never realized the pain that he suffered. For years he would awaken from nightmares screaming in Japanese, and we NEVER had rice for dinner. I recall asking why and he said that it was only fit for rats to eat.-- Don Matthews, grandson |

We had to work very hard for the amount of food we got, which was a small bowl of rice and watery slop three times a day. Once in a while we would get a small piece of fish. Some of the men would go out in the garden and steal vegetables. Several of them got caught and got beat until their buttocks was raw. We did not have any matches so I made an electric lighter. The Nips found it with three others. We all owned up making them but they beat everybody anyway. Some of the men were not able to walk from these beatings.

About Mar. 7, '43, they rigged up a place to make bread. It was not baked in an oven. They steamed it on top of the stove and it was very soggy. We got this bread once a day. When we got bread, we did not get any rice. Each man got a loaf which was about six inches square and 1½ inches thick. With this we had hot water. We had to boil all the drinking water as the Nips said it was poison. As you know, the Japs use human fertilizer on their gardens and our drinking water was very unsanitary.

Our cook went to work in the kitchen Oct. 23, '43. We thought maybe we would get a little more to eat, but the only ones that got fat were the cooks. Once while at Camp 18, one of the men done something that was not just right and made EGAWA, the camp commander, mad. He would not give us our loaf of bread that night. We only got half of a loaf. He threw the rest in the garbage. As I said before, this EGAWA was a Navy man. We heard he was going to leave and that the Army was going to have charge of the camp. We thought maybe it would be a little better.

The Army moved in Oct. 10, '43, under the command of a Second Lieut. by the name of EKAYGOMI [Ikegami]. Everything went fine for a week or so, then he started to beat us. Every night some one was getting a beating. If he thought the Nip soldier was not hitting you hard enough, he would take the club himself. I could call him by some other name but it may not pass the censor.

Each man was supposed to of got a American Red Cross box of canned food every so often. We never did get a box to ourself at this camp. Once we got a box to every twenty men, another to every ten men. After the Nips helped themselves, there was not much left for us.

Feb. 1944

I was taken sick with pneumonia. I was sick for about a week, working every day before they would let me go to the hospital. This hospital was just a building separate from the barracks. You were allowed to stay in bed, but did not have any medical care. If a man got low enough, they would call a Dr. out from town. He would give the sick man a shot in the arm and the next day the man would die. I got very low and weak. At that time I weighed 112 lbs. I now weigh 180 lbs.

Several of the men had Beri Beri. Their legs and feet would swell until you would think they were going to burst. They could not get their shoes on. The Japs would give them a pair of grass slippers and make them go out and work. One occasion when the Japs wanted some men to unload coal, they picked out three other men and myself who were all sick. I refused to go and the Jap beat me. He finally let me go back into the barracks. These other three men and myself were taken to the hospital and they died from exhaustion and overwork. We lost 52 men while at Camp No. 18. Some died from pneumonia, some from worms, but all from lack of food. One man, Knudt Farstvedt, who lived at Clackamas, Oregon, died 3/26/43 from worms. After he died, a worm crawled out of his mouth. The men were buried in a cedar box filled with straw and layed to rest on a hill near the dam. Oreal Johnson acted as chaplain. Oreal Johnson acted as chaplain at all of these burials and did a very good job under the circumstances.

The winters in Sasebo are very cold. We had about six inches of snow. The men would heat rocks to take to bed. The Japs found the rocks and everybody that had one got a beating. They had several Koreans working at this camp. The Japs found some rocks in their barracks. They beat the Koreans, then made them walk in the snow barefooted for about an hour.

April 17, '44

We left this camp and went to Fukuoka Camp No. 1. We were put to work making an airport. Here we did have medical care as there were some English soldiers there. There were several English officers, one English Dr., one American Dr., and two Dutch Drs.

We were treated a little better but not much. The food was the same rice three times a day, but we were allowed tea with our meals. We did not get as many beatings at this camp, although we were slapped around quite a bit.

We had inspection of quarters about once a week. It seemed every time they had inspections, the Nips would get drunk, then they would beat up on us. One time I did not have my bunk and clothes fix to suit the Nip and he hit me and knocked me down, then kicked me. My face was swollen and bruised for about two weeks.

There was a Nip by the name of Katsui (KAT-SEW-E) [Katsura], he could speak English and had charge of the work detail. He was pretty rough on the men whenever he got a few drinks. One time a gang was digging a ditch in water up to their knees, the weather was very cold. The men got their work finished and clumb out of the ditch, but he made them get back in the water and stay until quitting time.

Dec. 3, '44

230 of us left this camp and were taken to Fukuoka Camp No. 23 to work in a coal mine. Camp No. 23 was paradise in comparison with the others. We had good quarters, a pad to sleep on, five blankets each, and every man had a hot water bottle. We had a very good bathhouse and plenty of hot water. We were allowed to take a bath every day and wash our clothes. This kept down the bugs to a certain extent.

This coal mine was very unhealthy for the men that worked underground. I did not have to go below as I was one of the older men. Even the bosses treated us better, maybe it was on account of them losing. The camp commander at this camp seemed very pleasant. He let us have a Xmas tree Xmas eve, gave each man a Red Cross box and put on a banquet for us, had a little entertainment. We even had a small drink of saki.

Several of the men got very hard beatings over these Red Cross boxes. They would steal canned food from each other. Some of our own men told the Nips and these men got beat and put in the guardhouse. Men will do most any thing to get something to eat when they are hungry. I have ate garbage which the Koreans threw away; also cat and snakes. The Japs took a detail out to catch dogs, but the dogs were too fast for them. I could eat most anything, but when I saw the Japs eating snails, that beat me.

Aug. 15, '45

We stopped working in the mine. The next day, a Jap interpreter told us they had quit fighting but for us to stay in camp. A few days later he told us the war was over and we could go outside of camp. Some of the men went out and came back with chickens, rabbits or anything to eat and did they put on a feed. I could not get around very good as my feet were swollen with Beri Beri. I did not get out and get any chicken. But did I fill up after I got home.

Aug. 28, 30, '45

American planes dropped us food and clothing.

Dad didn't want to fly home from San Francisco so Mom took the Greyhound bus down there to get him. On the bus trip home, the other passengers learned of his story and were very kind to him. He said that one of the things that he missed the most was pie, so at every stop someone would get off the bus and bring him a piece of pie. At one stop, the driver got off and brought him a whole pie to eat! When they arrived home, Virginia (his youngest daughter), Aunt Muriel (his sister in-law) and I went to the station to meet them. The bus doors opened and people started getting off the bus. After a dozen people or so, we saw Mom and she was pointing to a little bent over man whose hat and coat were too big for him. As he got closer, I looked in his eyes..........and it was Daddy! When he came home, he weighed 112 pounds and he had cigarette burns all over his back. -- Florence A. Hughes, daughter (Don's mother) |

The American soldiers came to get us about Sept. 10, '45. We left camp Sept. 19, '45, and were taken by train to Nagasaki, which was eight-hours ride, deloused and given coffee and cookies. We were loaded on a boat and, as I had Beri Beri, was put in the sick bay. We were taken to Okinawa. I caught cold and was taken to the hospital. They thought I had pneumonia. I was held at Okinawa for observation. They took several pictures of my chest and said I had spots on my lungs. I finally talked them into letting me come home. I left Okinawa Oct. 8, '45, on the hospital boat Sanctuary and arrived in San Francisco Oct. 21, '45. I was taken to the Marine hospital at San Francisco for two weeks and landed in Portland Nov. 4, '45.

I often wondered what became of the 98 men we left on Wake Island. But I found out later that the Japs blindfolded them and shot them Oct.7, '43, according to a testimony made by a Jap by the name of Toumiro Miyaki. Former Wake Island Commander Shigematsu Takaibara, and Lt. Commander Soichi Tachibana stood trial in the War Crimes Trial for this mass execution. Miyaki also testified that another American was beheaded in May 1942, meaning Julius Hoffmeister.

(signed) C. D. Howes

INSTRUCTIONS CONCERNING QUESTIONNAIRE

If you are a paid-up member in the Workers of Wake, Guam and Cavite and an ex-Prisoner of War (not dependent member) please fill in the accompanying questionnaire to the best of your ability and memory.

If you have supporting records, such as a diary, to help you, so much the better. Maybe some old friend who was in the same prisons with you might help to remember some of the answers required. You must, realize that it is you only who can supply most of the information which is to explain why you are entitled to collect benefits that may be had under a Tort claim. No one else can supply the necessary information but you.

You are invited to ask friends to help supply dates and names of places, etc., but, this is your claim alone.

It is necessary that this form be completed and sent to your treasurer, Lindley H. Pryor, 429 North Holly Street, Medford, Oregon, by February 1, 1951, in order that Mrs. Mary H. Ward can have them in Washington, D, C. in time to be of any value to you,

If you are a "dependent member" fully paid in the Workers of Wake, Guam and Cavite, this "Statement of Dependent" should not prove difficult in filling it out properly. Simply answer each question carefully and to the best of your knowledge.

[NOTE: If anyone can supply me with the questions for these next two questionnaires, please let me know.]

Answers to questions:

1. Howes, Claude Davis

a. Yes.

b. Same.

2. 238 N. Fargo St., Portland 12, Multnomah, Oregon

3. 238 N. Fargo St., Portland 12, Oregon

4. 238 N. Fargo St., Portland 12, Oregon

5. Dec. 4, 1893, Minneapolis, Minn.

6. American

7. Oregon

8. Pipefitter, electric welder

9. Fireman

10. Fireman, evaporator operator, digger, engine operator, pipefitter, boiler repairs, repairs to machinery, acetylene burning, oiler

11. Gateman on bridge (where I am sitting most of the time)

12. Employed

13. Due to my physical condition traceable from being a prisoner. I had to change my occupation to a much easier one as my feet and legs swell when I stand for too long a period. Also I get pains in my back and have a bad heart. I get short of breath.

13a. Portland, Oregon

13b. Portland, Oregon

14a. My contracted rate of pay was 145.00 per month, which was raised Oct. 1941 to 180.00 per month. We were to work a 48-hr. week with time and one-half for time worked over 48 hrs. We were promised all the overtime we wanted to work. We would not need any heavy clothes, such as long underwear or heavy shirts as the weather on Wake Island was very warm.

14b. Transportation from the Mainland to Pacific Islands and all incidental expenses such as subsistence, medical examination, vaccination, photograph, etc., were to be paid by the Employer. The contract for employment at Wake Island required a man to stay only 9 months on the Island. If the employee completed his contract, he was to receive his salary until his return to the port of embarkation. If an employee was injured or sick while on the Pacific Islands, he was to be placed on compensation in lieu of his monthly salary. For the fourth month of employment on Wake Island, an employee was to receive a bonus of (Refer to Contract).

14c. No.

14d. None.

15. Dredge fireman

16. Yes. Evaporator operator, digger, engine operator, pipefitter, boiler repairs, repairs to machinery, acetylene burning, oiler.

17. 145.00 per month, with bonus after the third month.

18. It was increased Oct. 1941 to 180.00 per month.

19. Portland, Oregon, April 25, '41

20. There was no cost of fare. I rode the dredge and worked on the dredge from Portland to Wake Island.

21. Dredge Columbia.

22. June 6, '41

23. Wake Island

24. Only to Japan as a prisoner.

25. None, as I rode the dredge from Port. to Wake

26. Good.

27. Naval Air Base, as part of the National Defense Program.

28. Copy of Contract

29. Yes.

30. No.

31. No.

32. No.

33. While at Camp No. 18, Sasebo, we were working on a concrete dam. We were carrying sacks of cement on our backs and piling them about 12 ft. high. We piled the sacks so as to make steps. I had only carried about six sacks when I fell off the pile and hurt my back. The Jap boss tried to make me carry more but I could not as my back pained me considerable. The Jap beat me severely with a sledge hammer handle which most of them carried. Although my back pained me, he made me do other work. We did not have any Drs. at Camp 18, only a Japanese medic to dress our wounds. If we needed a Dr., they would order one out from town and this was very seldom done. If a Dr. did come out from town, he would give the man a shot in the arm and the man would die in the near future. This Camp No. 18 was the worst camp I was in. We even heard about this camp while waiting for our train at Yokohama from a Jap that could talk English. He said it was a very bad camp. We got several beatings at this Camp No. 18 which I will describe in question No. 61 and No. 66.

34. Yes. U.S. Army at Okinawa. T.B. (get copy of exam).

35. Excellent. We had to be in good condition or they would not sign us up.

36. Very very poor.

37. I have pains in my back, my feet and legs swell when I stand for a long period. I have pains in my left chest mostly when I lay on my left side. It makes me very short of breath. The Veteran Administration Dr. stated I should be taking something for my heart. He mentioned Digitalis. I have defective vision and arthritis.

38. Yes. U.S. Marine Hospital, San Francisco, Calif. Beri beri, hematuria, hypertrophic, malnutrition, helminthiasis, arthritis, defective vision.

39. Yes. Dr. Davis, U.S. Public Health.

40. No.

41. Copy no. of bombings

42. 15 days.

43. None whatsoever.

44. About 10:00 AM Dec. 8, '41, Mr. Dan Teeters, the Superintendent of the Island, came aboard the dredge and told us that the Japs had bombed Honolulu, for everyone to go ashore. As there were no dugout or shelter from the bombing, we did know where to go. We thought we had better eat something before going ashore. The Japs came over before we had finished our lunch. We went ashore and milled around the mess hall. Stanley Carlson, our chief engineer, suggested we get away from the buildings. Some of the men were detailed to fill sand bags. As Carlson was our boss on the dredge, I went with him and five other dredge hands. As we did not have any shovel to dig in with, we had to lay on the ground for two nights. We finally found a shovel and managed to dig a hole about two feet deep as the coral ground was very hard digging. We put 2X4 over the hole and covered them with mattresses. We ate at the cookhouse the second day, but after that we had to russel our own food. There was plenty of food in the warehouse but it was locked. All my gang had to eat for several days was sardines and catsup which we found in the brush.

45. None.

46. How was we to know that Japan was getting ready to attack the Island if Pearl Harbor didn't know that they were going to be attacked?

47. Sometime in Nov. 1941 I heard there was an order out to evacuate the women and children from the Island. But I did not hear nothing in respect to attacks or removal of the men.

48. Yes. The Clipper which carried mail and passengers to and from the Philippines was laying at dock when the Jap bombers came over and bombed the Island the first day. The crew unloaded the mail and cargo to the dock, and all the officials except Dan Teeters our Superintendent left on the Clipper for Honolulu. As I stated in Question No. 47, sometime in Nov. 1941 I heard that there was an order out to evacuate the women and children from the Island. About this time, Nov. 1941, Mrs. Teeters, the wife of our Superintendent Dan Teeters, evacuated the Island.

49. Yes. There were NO American ships that came to Wake Island between the time of the first raid and capture of the Island.

50. Yes. Saturday, Dec. 20, U.S. PBY landed at Wake Island some time in the night and left early in the morning. Not that I know of.

51. The contractors had no ships or airplanes in the vicinity.

52. About 1100.

53. Dec. 24, 1941. The gang I was with did not surrender until then.

54. All I know is Dan Teeters came aboard the dredge about 10:00 AM, Dec. 8, 1941, and told us that Japan had bombed Honolulu and for us to go ashore.

55. Yes. I helped fill sand bags for the Marines. I also went out with details at night to move the guns and ammunition. At the request of Leal Russel under the direction of the Marines in charge.

56. No. As I was on the dredge, it was very inconvenient for some of the dredge crew to take the training. In regards to the time the training was given. Although I know several of the men on the Island did get training on the guns. As I am a vet of World War No. 1, I have had some military training.

57. No. Under our contract we were not allowed to take firearms to the Island.

58. Yes. Marines. Major Devereux.

59. Not known exactly. Increased to about 500.

60. Yes. The Marines did not go out on work details, so consequently they did not get beat around like we did.

61. Lack of food was the greatest privation. All we got to eat was a small bowl of rice three times a day, and a small bowl of water soup made from vegetable tops or weeds. We got a small piece of fish about twice a week. At Camp No. 18 we got no sugar, salt, meat, and the only vegetable was what they call DYCONS [daikon]. Our housing was very poor. When it rains our beds would get wet. Our clothing and shoes were very poor for the rain and snow as we had to work in all kinds of weather. We did not have any place to dry our clothes overnight. If we got around a fire to get warm, the Jap boss would beat you with a club. We got very little water to drink as it came over the hill where there were gardens. As the Japs put human fertilizer on their gardens, the water had to be boiled before using.

As I stated in Question 33, I hurt my back while carrying cement at Camp No. 18. We got several beatings which was an injury to our body. I made an electric cigarette lighter as we had no matches. The Japs found it and 3 or 4 others which some other men had made. Although we owned up to making them, everybody got a beating. George Dillon, one of the prisoners at Camp 18, hit a Jap boss (we called Grandma) with a shovel. Everybody in camp got beat for this, and what I mean we got BEAT. They lined us up in rows about 10 feet apart so the Jap would have room to swing his club. We had to hold our hands over our head. The Jap was supposed to hit us on the buttocks. Sometimes he would hit high or low, knocking the man down. The Jap knocked me down and as I could not get up quick, he kicked me. When I got up, he beat me some more. I was lame and bruised for several days. Oreal Johnson from Boise, Idaho, could not walk for several days from this beating. If the camp commander did not think the Jap soldier was hitting you hard enough, the commander would take the club and beat you.

While at Camp No. 18, I did not feel very good and wanted to stay in bed. The Jap made me get up and report on sick call. It did no good, I had to go out and work. Several days went by and I got worse. Finally, I refused to get up as I was very sick. The Jap let me stay in from work. The Jap wanted some men to unload some coal. He picked three other sick men and myself. The other men went but I was too sick and weak. I weighed 112 lbs. at the time. My average weight is 165 lbs.

These three men and myself were put in what they called Byoin or hospital. It was a building by itself, very poorly constructed, and the only heat was a charcoal open fire. We were not fed as much as the men working, so when a man got sick, he would not get enough or the right kind of food to bring him back to health. While I was in the hospital, several of the men died. The men were dying off like rats. I got very bad with dysentery and pneumonia, but would not give up and let them call a doctor out from town as I knew what happened in the past, which I explained prior in Question 33.

The three men that unloaded the coal all died from pneumonia. Stanley Simmons, one of the patients, would heat our rice and soup on the charcoal fire, and I give him credit for me being here today. William Hogan, one of my friends from Portland, was very sick with pneumonia. He thought he was going to die. He called over to his bunk and said, "Curley, if you get home, explain to my wife and tell her I tried to pull through."

I also suffered from Beri Beri, dysentery, hook worms, malnutrition, hematuria, and arthritis. When you went to the toilet, you had to ask the guard in Japanese. If you did not say it right, he would hit you with a club. I had a fellon(?) on my little finger and from the lack of medical treatment, I lost the end of it. After I got out of the hospital, I was made to go to work. As I was very weak, I had to rest once in a while. The Jap boss (whom we called the RAT) would hit me with his sledge hammer handle and make me go to work. One time while in line, this RAT gave us "left turn." As we could not understand him, we turned right. He beat everyone in the gang (20 men).

We were moved from Camp 18 4/17/44 to Fukuoka Camp No. 1. The Japs at this camp delighted in having inspections of bunks and quarters so they could slap some one around. I did not have my clothes piled just right. The Jap hit me and knocked me down. Then he kicked me. My face was bruised for several days.

62. The Japs took everything.

63. $309.45

64. I was on Wake Island until 9/30/42, then taken to Sasebo Camp 18, Japan. 4/17/44 we were taken to Fukuoka Camp No. 1. 12/3/44 I was taken to Fukuoka Camp No. 23.

65. While on Wake Island, we had to fortify the Island, such as pillboxes, barb wire, dugouts, of which there were none. I also worked on a paint gang. At Sasebo Camp No. 18, we were building a concrete dam. At Fukuoka Camp No. 1, we were making an airport. We had to unload rocks from freight cars. At Camp No. 23, Fukuoka, I worked at a coal mine. I did not go below ground as I was one of the older men. I worked making briquets which was very dusty and unhealthy. We also had to dump cars loaded with waste from the mine. Our Jap boss was good to me as he could understand. But his superintendent would beat me whenever he came around. I was at this Camp 23 Fukuoka when liberated.

66. As I stated in Question No. 53, my gang, Stanley Carlson, Tommy Gillen, Owen J. Thomas, William Harvey and myself, C. D. Howes, did not surrender until Dec. 24, '41. We gathered our belongings and started towards Camp No. 2. As we were going up the road, two Japs were coming towards us. They stopped us and asked what time. Thomas and Gillen pulled their watches out and the Japs took their watches. Carlson and Harvey, who had been to Japan before on boats, could understand Japanese a little. Carlson asked these Japs where to go. We went over to one of the buildings and the Jap there took our suitcases, searched us, took everything but one package of cigarettes. The Jap then slapped our faces, loaded us on a truck, and took us to the airport where the rest of the men were. These men did not have any clothes as the Japs had stripped them when taken prisoners. If they had shorts on, they were lucky. Although Wake Island is very warm, it is chilly at night when you don't have anything to cover up with. We had to stay on the airport that night, Dec. 24, '41.

Our Xmas dinner consisted of bread and water. The water was in cans which had been used for gasoline. You can imagine how that tasted. All the sick and wounded had to stay on the airport two nights out in the open. We were marched to Camp No. 2 Xmas night. As we were marching, I noticed an American flag on the ground and the men were walking on it. This really hurt me as I know our flag had never been trampled on before.

The next day, Dec. 26, '41, we were taken on details to find food which the contractor men had hid in the brush. A Jap officer (KATSUMI) went out with us. He could talk English. I heard he was an importer at Chicago before the War. If the men would try to eat any of the food, he would pull his gun and threaten to shoot them. I worked a couple of months cleaning the dredge as the Japs wanted to keep it in running order. Then I worked building pillboxes. These pillboxes were concrete, about two feet thick with plenty of reinforcement. I also put up barb wire around the Island. I helped make dugouts which we used when the American planes came over the Island. Feb. 24, '42, U.S. planes bombed and burnt the top deck of the dredge which was wood constructed. Several men were detailed by the Japs to go to the dredge and put out the fire while U.S. planes were still in the vicinity. I went on the paint gang Feb. 24, '42, as the contractors had plenty of paint. The Japs painted everything on the Island. Feb. 26, we were painting on the radio station when one of the Japs came running out and told Joe Troy that two American swam ashore. We heard later they were aviators off the Enterprise. These aviators were kept blindfolded while on the Island. They were taken away but I do not know where.

May 10, '42, while I was on Wake Island, Julius Hoffmeister broke into a warehouse and stole some liquor and food. The Japs caught him in the act. They kept him in the guardhouse a couple of days. Finally they dug a hole, then they blindfolded Hoffmeister and had him kneel down on a board at the end of the hole. One of the officers took a sword and cut off Hofmeister's head and the body fell in the hole. Several of the American foremen were made to witness this execution.

I left Wake Island Sept. 30, '42, with 264 other men. We were taken to Japan. 98 contractor men were left on Wake. Oct. 7, '43, they were marched to the beach and shot according to a testimony made by Warrant Officer Toumiro Miyaki at a war crime trial. Some of these men worked with me on the dredge. We were taken to Japan on a double-deck ship. I was in the lower hole. It was very hot. We would take turns and fan the men so they could get some sleep. Some of the men were taken off the boat at, I think they called it, Takewa Bay. These men were overcome with the heat and were taken to a hospital.

We landed in Yokohama Oct. 11, '42, and had to stay at RR station a couple of hours waiting for our train to SHIMONOSEKI. A Jap soldier at the station knew where we were going and he said, "Camp very bad," (meaning Camp 18, Sasebo). When we arrived at SHIMONOSEKI, we were taken upstairs in a building and had to wait about two hours for our boat to KYUSHU Island. While waiting, one of the Japs took a collection of Japanese money, which some of the men had collected on Wake, and went out and got us some cigarettes. I think we got one apiece.

We were taken to KYUSHU, then loaded on another train, had several meals, and arrived at Sasebo Oct. 13, '42. We were marched through town and at the foot of a hill were loaded in trucks and taken to Camp 18. Here we were issued blankets full of fleas and lice. We could not sleep at night as we had too much company (meaning fleas and lice). That heat on the boat really took the sap out of us. We thought maybe we would get a day's rest but we had to go to work the next day. This camp was under the Navy and the camp commander was a Sergeant by the name of EGAWA. He was very cruel and delighted beating someone or watching it done.

We were put to work building a big concrete dam. The men were split up into a gang of 20 men, each gang had a boss. The bosses all carried a club, most of which were sledge hammer handles. If you did not understand what the boss said, he would hit you with his club. I got beat lots of times as I could not learn their language. When we had to go to the toilet, we had to go past the guard and ask him in Japanese if we could go to the toilet. If you did not say it right, he would beat you with his club. Some of the men carried cement, some shoveled sand, and some shoveled rock.

As I stated prior in Question 33, I hurt my back while carrying cement, and in Question 61, where we got beat for George Dillon hitting the Jap with the shovel. Also in Question 61 about me making the cigarette lighter. It seemed like someone was getting beat every night. We always knew before we got in from work if we were going to get beat. If everybody was going to get beat, the Japs would say, "Bow-Low Hi-que" [bo wo haikyu]. Several of the men got beat for stealing something to eat. I have seen some of these men after they got beat in the bathhouse and their buttocks would be bleeding. I stole food, too, such as garlic and onions, but I never got caught. I hate to admit it but I ate garbage while at Camp 18. A man will do most anything for food if he is really hungry.

The food was about the same in all the camps I was in. A small bowl of rice and bowl of watery soup. We got a small piece of fish about twice a week. We had to work hard and we lost about 55 men at this camp from our work and malnutrition. Also several died from dysentery, worms, and pneumonia. We did not get very many cigarettes, about one package a week. We were credited with 10 sen a day for working. Sometimes it would be at longer intervals. We had to pay 60 sen for a package of cigarettes, so we had to work six days to get 10 cigarettes.

They changed the guard every month. We would just about get acquainted and they would ease up on their clubs. Then a new guard would come and we would get beat more. This EGAWA really was a _ _ _ _. I can't think of a word that would suit him. One of our men, Joe Troy, was working in the kitchen with the Japs and he noticed a tag on a flour sack. It was American Red Cross flour. I don't know how he did it but he talked to Egawa into making bread for the men. So we got bread at night for our supper. When we got bread, we did not get any rice. Once in a while they would make a gravy and dumpling. This really was a treat after eating rice so long. Once somebody did something that made Egawa mad, so we only got half a loaf of bread. Now these loaves were about six inches square and about one and one-half inches high. You can imagine how heavy they were.

They changed the camp commander Oct. 10, '43, and the Army moved in. The camp commander's name was EKAYGOMI [Ikegami]. He was just as bad as EGAWA, only worse. If he did not think the soldier was beating you hard enough, he would take the club and beat you. (I explained in Question 61 I was in the hospital and very low.)

We moved to Camp No. 1 Fukuoka 4/17/44. At this camp we worked on an airport. We got slapped around quite a bit, but did not get beat like we did at Camp 18. The housing here was very poor. They had straw on the roof and you could see the rats building their nests in the straw. The roof leaked bad when it would rain. The food was about the same, only we got tea to drink instead of hot water. Once in a while they would make tea with so much sugar in it that it was like syrup, but otherwise we got no sugar or salt with our tea or rice.

We had several English, Dutch and Java soldiers at this camp. We also had several English officers, two Dutch Drs., 1 English, and one American. As I told you before, I lost the end of my little finger. When I went to this camp, I reported on sick call as I still had my finger bandaged. I showed it to the English Dr. He was going to cut it off but did not have his instruments ready, so I had to go back next day. He took the bandage off and the end of my finger came off with the bandage, it was so rotten. I still had Beri Beri, so this English Dr. gave me a shot in the spine. He told me to lie down for a certain length of time. If you raised your head, it would pain something awful. These English officers did not go out of the compound and work, but the other soldiers did.

We were only allowed to smoke at certain times, in the morning before going to work, about 10:10 AM, at noon, at 2:30 PM, then after we came in from work.

We had a guard at this camp we called Buck Tooth. We were supposed to stand and salute him whenever he came through the barracks. As I had Beri Beri, I could not get up very quick. He would come down to my bunk and bump me on top of my head with his gun. He kept the top of my head sore most of the time.

I was moved from this camp 12/3/44 to Camp 23 Fukuoka. Here I worked in a coal mine. This was paradise compared to the other camps. We had a waterproof barracks, 5 blankets each, and every man had a hot water bottle. We had a large bathhouse and plenty of hot water. You could take a bath every day. We were really working for the coal mine, not the Army or Navy. We were treated much better at this camp.

The camp commander could talk a little English. At Xmas time, he let our cooks cook something different and really put on a banquet for us. He even gave us a small drink of sake, after which we had some entertainment put on by the prisoners. We each got a Red Cross box. This was the first time we had a box to each man. Some of the men ate so much that they were sick. We got three Red Cross boxes in the 9 months we were there. Maybe this was on account that they were losing the War.

This mine was very unhealthy for the men that had to go below ground. And it was very dangerous. Several men got hurt, some got their feet smashed. One man, Jack Kilburn, lost control of his legs and could not walk for several months. We had a cow at this camp and we got a cup of milk about every 10 days if we had the money in our account to pay for it.

The food was about the same, rice and soup and not much of it. We did get beans at this camp once in a while whenever they did not have enough rice. We had to walk about 1/4 of a mile from the barracks to the mine. As my feet and legs were swollen with Beri Beri, it was very hard for me to walk and keep up with the rest of the men. As I stated prior, this camp was paradise compared with the others.

We stopped working in the mine Aug. 15, '45. A Jap interpreter told us they had stopped fighting but for us to stay in the camp. Then a couple of days later, he told us we could go outside but we had to report when we went out and when we returned. Finally the Japs moved out of the compound and we could do as we pleased. I forgot to mention most of the men at this camp were soldiers that were taken prisoners in the Philippines. There were about six American officers who took charge after the Japs moved out. We butchered the cow Aug. 20, '45. We got some of the meat, but the Japs got most of it.

Aug. 28, '45, American planes dropped food to us. Aug. 28 more food was dropped. About this time, some Red Cross workers visited the camp whom we had not seen since taken prisoner. The Americans came after us and we left camp Sept. 19, '45. We went by train to Nagasaki, then by boat to Okinawa where I was hospitalized.

67. I described prior about Julius Hoffmeister getting his head cut off. Elbert Knox was in the guardhouse at Camp 18 and very weak. The Japs beat him and he died.

68. Sept. 19, '45. I think I described this question prior in Question 66. We were taken from camp by truck to train, then to Nagasaki where we were deloused and gave doughnuts and coffee. We were taken to Okinawa where I was hospitalized.

69. On the USS hospital ship SANCTUARY as I was in very bad health to travel otherwise. I don't know who paid passage.

70. San Francisco, Calif. Oct. 22, '45, Pier 7.

71. We were unable to communicate with our family for two years. My wife did not know of my whereabouts until 1943. It is very hard for me to answer these questions when I think of my prisoner life. Words cannot express what we went through -- hunger, poor housing, very little water, very little soap and lousy beds. While at Camp 18, we found a root that was sweet which men would chew to satisfy their thirst. If the Jap caught you chewing, he would beat you and make you spit it out.

72. Not known exactly.

Answers to questionnaire:

EA.922647

3. Portland, Oregon, March 22, 1941

4. Wake Island

5. Dec. 23, 1941

6. Japanese

7. Sept. 19, 1945

8. Oct. 22, 1945

9. 44 months, 19 days

10. Wake Island, Dec. 23, '41 to Sept. 30, '42

Sasebo Camp No. 18, Oct. 13, '42 to April 17, '44

Fukuoka Camp No. 1, April 17, '44 to Dec. 3, '44

Fukuoka Camp No. 23, Dec. 3, '44 to Sept. 19, '45

11. (Wake Island) As the men I was with did not surrender until Dec. 24, the day after the capture of the Island, we were slapped in the face and kicked by the Japanese guard. We were then taken to the airport and made to sleep in the open without any covers. Our Xmas dinner consisted of bread and water. The water was in cans which had been used for gasoline. As we could not understand their language, they would beat us with a stick if we did not do as they commanded.

When going from Wake to Yokohama, I was two decks down on the boat. It was so hot we could not sleep. Part of the men would lay on the steel deck and some would fan them so they could sleep.

Sasebo Camp No. 18 was the worst camp for beatings. I just cannot recall all of them as all of the guards carried sledge hammer handles. And if you did not understand, they would beat you. If one man did something the guard did not approve of, the whole camp got a beating (265 men). One of our men, George Dillon, hit one of the guards with a shovel. We were all beat for this (265 men). I was made to hold my hands over my head and the Jap guard beat me on the buttocks about 12 blows. He knocked me down and then kicked me until I got up and then beat me the same more. He must have hit me in a vital spot as my back pained me for several days. They beat us something awful and it was hard to take when you could not hit back. I still have trouble with my back at times.

I made an electric cigarette lighter and the Japs found it with 3 or 4 others. We all owned up to making them but they beat the whole camp for this. Tommy Gillen had his hand broke from this beating.

One morning our guard we called the RAT gave us "left face" and we turned right. Our gang of 20 men got beat for turning the wrong way. The guard spoke in Japanese and we could not understand his command.

When you went to the toilet, you had to go past the guard at the gate. You had to tell him in Japanese where you were going. If you could not tell him, he would beat you with a club. I got several beatings for this as I couldn't pick up their language.

I got beat for taking a hot rock to bed. I got beat for not getting up in the morning when I was very sick. The guard beat me and I had to go outside in the cold for sick call. I had to work several days before they would let me stay in. At this time I only weighed 112 lbs. My regular weight was 165 lbs. We were so thin from lack of food the guard would hide us when any big shot officers would come around. If I tried to get around a fire to get warm, I was beat and made to go back to work.

Fukuoka Camp No. 1

I got several beatings at this camp from Buck Tooth, the guard, as I was sick from a shot in the spine for Beri Beri and could not stand up and salute when he went through the barracks. I got beat for not having my clothes piled just right when we had inspection. The guard hit me in the face with his fist and slapped me, he knocked me down, then kicked me. Every time the guards got drunk, they would have inspection and someone would get beat.

Fukuoka Camp No. 23

I got slapped a couple of times at this camp by the Jap superintendent for not working hard enough. I was so weak I could not work. This camp was paradise to Sasebo Camp 18 and Fukuoka Camp No. 1.

12. I had dysentery which lasted about two weeks for which I received no medical care. I had pneumonia which lasted about 3 weeks for which I received no medical care but was allowed to stay in what they called the Hospital (2 weeks in hospital). I contracted Beri Beri about April 1943 and had it for about one year before I received any medical care. This I received when I moved from Sasebo to Fukuoka, which was a shot in the spine. I still had Beri Beri when I arrived in San Francisco in 1945. I had Beri Beri about 2 years. I think I still have some symptoms of Beri Beri as I have shortness of breath and have slight heart trouble. I have received no medical care, only rest and good food.

Malnutrition, which was caused from the lack of food. This I had during the time I was a prisoner about 44 months. I lost the end of my little finger which started from a scratch and turned to gangrene. I had it dressed by Ben Marsh, one of our men. He put merthiolate on it but it rotted off after about a month. An English Dr. at Fukuoka healed it for me (worms). I only weighed 112 lbs. during the time I was a prisoner. My average weight was 165 lbs. prior to Dec. 1941.

I was unable to work at my trade, which was pipe fitting and welding, due to my physical condition.

13. The food was about the same in all camps I was in. It consisted of a small bowl of steamed rice and a small bowl of watery soup seasoned with a fish head. This we got 3 times a day. About once a week we would get a very small piece of fish.

14. Malnutrition -- undernourished and starvation

Beri Beri -- swelling of the feet and legs such as dropsy, caused from eating polished rice which in polishing a vitamin is removed in the huskHematuria -- blood in the urine, caused from worms. The worms were sustained in the water which maybe was not boiled before it was rationed out to the prisoners.

Hypertrophic -- pertaining to heart and feet. I claim my heart trouble was sustained from Beri Beri. My feet are in very bad condition due to improper shoes.

Arthritis -- pains in arms and legs, sustained from sleeping in damp and wet bunks.

Defective vision -- pertaining to eyes. I wore glasses before going to Wake.

Helminthiasis -- I do not know what this word means.

15. The living conditions were very poor. At Sasebo we slept in an old cement shed on mats which were very hard. We were given cotton blankets full of fleas and lice. We could not sleep and get rest as the fleas and lice were so bad. I had to line my blankets with paper and grease my body with cup grease in order to get any rest. The toilets were very unsanitary, just a hole which caught the waste, then the farmers would gather it to put on their gardens. The toilet floor was always covered with maggots.

At Fukuoka the sleeping quarters were very very bad. The roof and walls were covered with straw and just full of rats. Sometimes they would fall on our bunks. Whenever it rained, our blankets got very wet as the straw was very poor roofing and the rats ate holes in it.

Our rice and soup was rationed out in square containers 8x8x10. One container had to serve 20 men. Two men were picked by the guard to dish out the food. We had bowls about the size of a restaurant soup bowl. The guard watched the men dish up the rice and soup to make sure they did not pack the rice. It was just put in loose.

One time we were working on a road and it was raining. The guard made us sit by the road and eat our dinner although there was a shack nearby. While we were eating, trucks were going by and splashing mud in our food. The guard just laughed and would not let us move. We had to work in the rain and as our clothing was very poor, made out of burlap and dyed green, we would get very wet and had no place to dry them overnight.

The first winter we did not have any stove or heat in our sleeping quarters and quite a few men died of pneumonia. The second winter we had oil drums for stoves but had very little wood, only the scraps that we could pick up around the dam which we were building.

The laundry facilities were very poor as we were gave very little soap. Very seldom we had soap to wash our bodies with. There were no barber facilities. We had to shave ourselves and have our buddies cut our hair. Most of us had our hair cut close or shave our head so the lice would not get in our hair.

The water was very unsanitary, as I stated prior, as it flowed through the gardens where they had put human fertilizer.

The work was very hard for a man that was not getting enough to eat. At Sasebo I was working on a concrete dam. Sometimes we had to carry sacks of cement on our backs and stack it in a shed. I fell with a sack and hurt myself. The guard beat me and tried to make me carry more but I was unable to as I hurt my back. Other times we had to shovel rock and sand. The guard would stand above on a walkway. If we quit shoveling, he would throw sand on us.

My shoes were wore out and the Japs had none. I had to wire the soles on as it had come loose from the upper. Once the Japs issued tabbies [tabi], a sort of tennis shoe with a split toe. These were very poor for rainy weather. I could not wear these as my feet were swollen from Beri Beri.

I did not get any mail from home until 1944. My wife and daughter says they wrote every day. I received only six letters in the whole time I was a prisoner. I wrote several cards to my wife but she only received two and that was sometime in 1944. My folks did not know where I was at until 1943. (Repairs to clothing)

ASSORTED NOTES IN HOWES' PAPERS

Left Associated Oil dock 4/25/41, 5 A.M.

Arrived Honolulu 5/12/41

Layed up Honolulu 9 days to repair light engine

Pulled out from Honolulu 5/21/41

Arrived Wake Island 6/6/41

Dec. 8, '41: The Superintendent came aboard the dredge about 10:30 A.M. and told us war had been declared.

We were heavily bombed and shelled until day of surrender 12/23/41.

My gang was taken to Sasebo Sept. 30, '42

Arrived Camp No. 18 Sasebo Oct. 13, '42

Left Sasebo April 17, '44, to Fukuoka Camp No. 1 until War was over.

Came home on hospital ship.

I weighed 112 lbs.

Major James P. Devereux

Commander of Marines

Winfield Scott Cunningham

Rear Admiral, U.S.N.

Cunningham went to Wake Nov. 28, '41

Dec. 7 (7 A.M. about) Pearl Harbor hit.

Wake hit Dec. 7, just before noon.

Wake shelled for 15 days. 16 days of battle.

Dec. 11, ships seen. We got 2 destroyers and damaged others.

Dec. 20, P.B.Y. landed on Wake with information.

Dec. 23, Japs landed on Island.

American casualties - 33 fighter squadron, 15 defense squadron, 33 to 80 civilians - actual figures not known.

Jan., Marines taken to Yokohama (Cunningham).

Dr. for contractors - Dr. Lawton E. Shank.

Dr. Shank stayed on Island with 97 contractor men, all were massacred by Japanese.

Civilians helped move guns and passed ammunition.

Dan Teeters, contractor boss.

Civilians volunteered for duty - About 38 percent of civilians.

At outbreak of war, 439 Marines on Wake. After first raid, 416 Marines left.

About 312 civilians helped defend Island, moving guns, passing ammunition.

Captain Wesley Platt, Wilkes Island.

The Oregonian

February 20, 1942

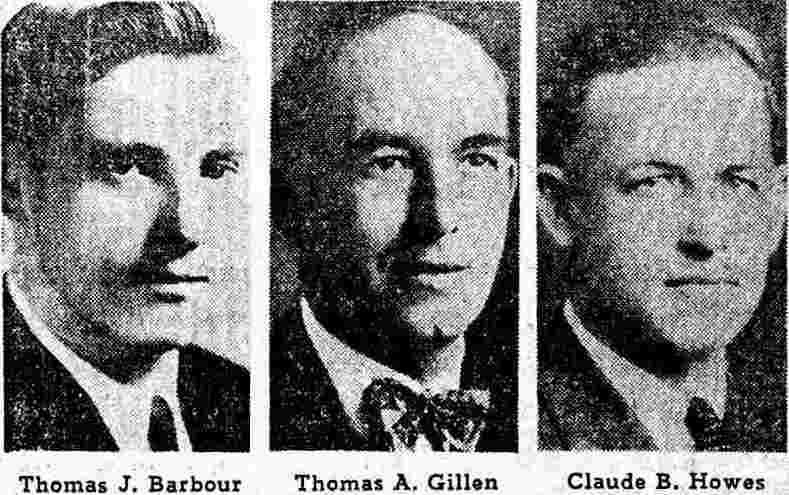

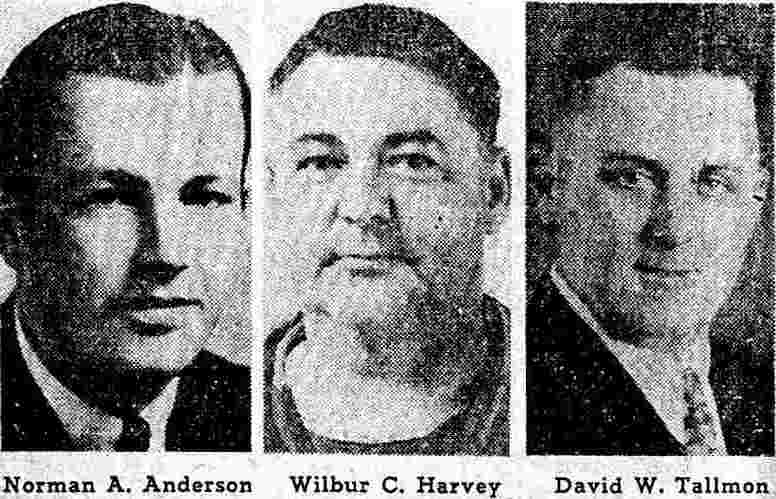

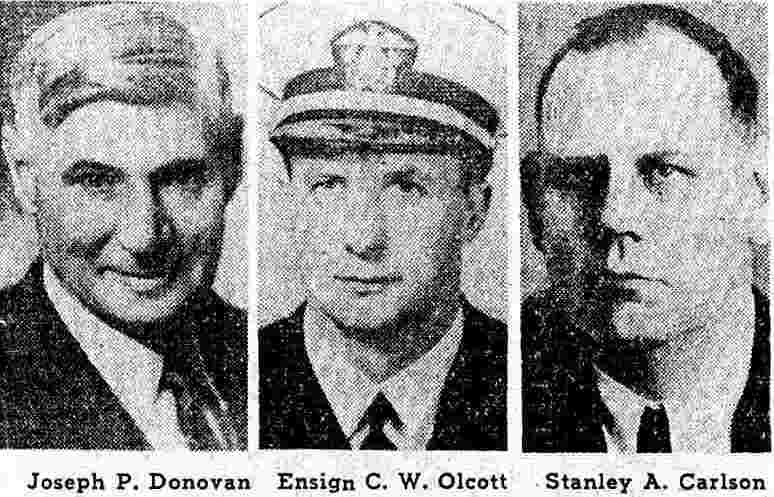

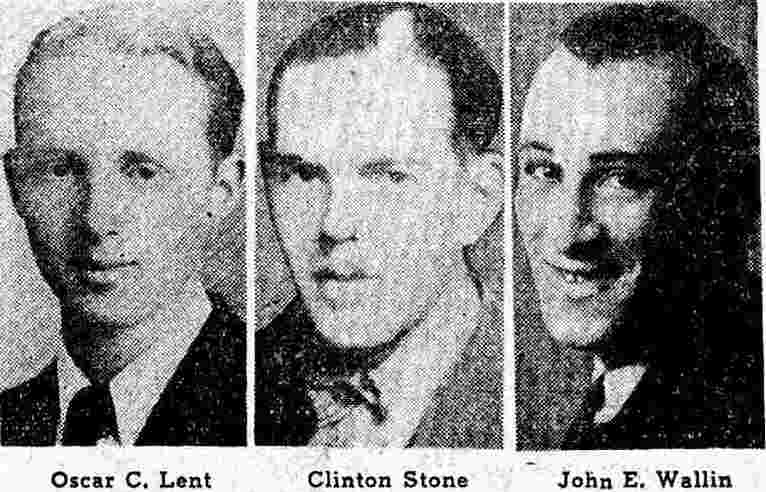

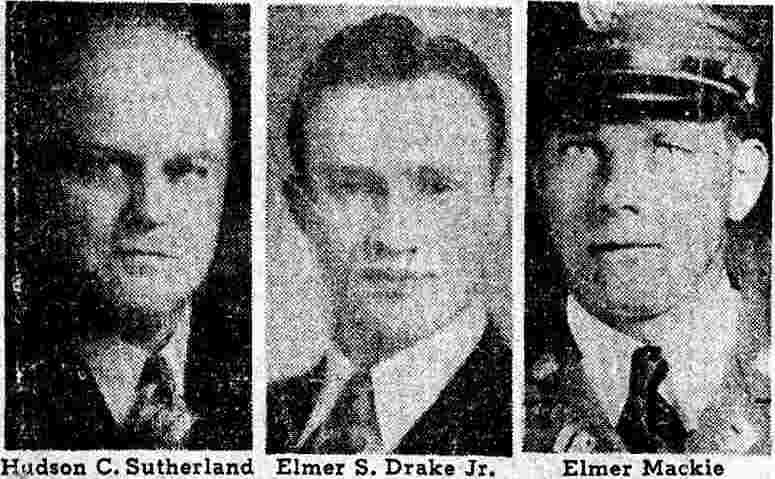

These Are Portland Men Reportedly Among Prisoners Captured by Japanese at Guam and Wake Islands

40 Local Men Listed as Probable Captives of Japs In Report Released by United States Authorities

Relatives and friends of 40 Portland men listed by the government Thursday as "probable" prisoners of the Japs buoyed hopes that the hapless group was still alive.

Publication of the list was the first news of 38 of the men, word having been received earlier about the plight of two of them -- Ensign Chester W. Olcott and Hudson C. Sutherland.

Olcott Ex-Grid Star

Ensign Olcott is the son of ex-Governor Ben Olcott. He was on a special mission at Wake with a small Company of naval men, arriving at the ill-fated island presumably a few days before the Jap attacks. Word that he was a probable prisoner was received several days ago by his father from naval officials. Young Olcott is an ex-Rose Bowl end of Stanford, and was stationed at the naval air station at Haneoke, T.H.

The voice of Hudson C. Sutherland, a graduate of old Portland academy and well known in local construction circles, who was a superintendent of a Wake project, was heard late in January in a broadcast from Tokyo. In the broadcast, apparently from a recording aboard ship, Sutherland was heard to say the Japs had given the Wake prisoners "good treatment."

Wife Resides Here

His wife is living with a friend, Mrs. Lillian G. Hamilton, at 7101 S. E. Gladstone street. Their daughter, a school teacher, is employed in Salinas, Cal.

In addition to Ensign Olcott, the other service men listed were:

Thomas Vernon Lusk, son of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas S. Lusk, 3131 N. E. Flanders street, who enlisted in the marine corps here May 12, 1939. He was at Guam.

Elmer Sidney Drake Jr., a corporal in the Wake marine garrison, son of Mr. and Mrs. Elmer Sidney Drake Sr., 124 S. E. 28th avenue, who was a member of the marine corps reserves until he enlisted January 12, 1940. He is a graduate of Roosevelt high school.

Malcolm Walker, machinists' mate, first class, formerly of 5236 N. E. 37th avenue, who first enlisted in the navy in 1934 and was long in the submarine service after completing courses at the navy's school in New London, Conn. He re-enlisted December 1938, and was stationed at Guam.

Merlin Winfield Ankrom, son of Mr. and Mrs. Claude B. Ankrom, 2131 S. E. 54th avenue, who had been a member of the naval reserves but enlisted in the marine corps here September 5, 1935. He was with the Guam marine detachment.

Stanley A. Carlson -- Mrs. Carlson, 6925 N. Campbell avenue, wife of the dredge Columbia's chief engineer, said she was "certain" the listing of her husband's name meant he was still alive, else she would have been notified otherwise immediately after the fall of Wake.

Thomas J. Barbour -- Hope for his safety was shared by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas L. Barbour, 5105 S. E. 38th avenue, Born November 2, 1919, in Victoria, B. C., Thomas was educated in Woodstock grade and Franklin high schools. He served two years in a CCC camp at Baker before leaving for Wake island last April. He wanted the dredge job in order to earn money to pay his way through college.

Nathan Smith Plummer, son of Mrs. Lelah B. Plummer, 3216 S. E. Stark street, who enlisted in the marine corps here October 20, 1939. He was at Guam.

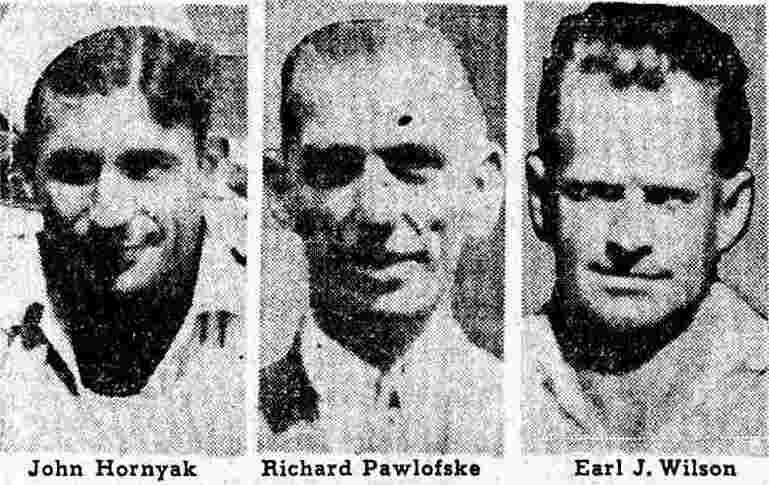

More than half of the 34 Portland civilians listed as "probable prisoners" were employees on the dredge Columbia at Wake Island. The dredge left Portland last April 26 in tow of a navy craft, arriving at Wake, after a stopover at Pearl Harbor, June 6.

Notes on many of the civilian follow:

Thomas A. Gillen -- Mrs. Gillen1153 S. W. 13th avenue, wife of the Columbia's first assistant chief engineer, re-echoed Mrs. Carlson's theory. Gillen was long chief engineer at Multnomah Lumber & Box company here. Last word from him was a letter written November 29 at Wake and received here December 3. Gillen was counting days until he could return, for his letter said: "It's only 93 more days now."

Norman A. Anderson -- His mother, Mrs. Carl Anderson, 6113 S. E. Rhone street, said she and her husband last heard from their son, a dredge employee, about Thanksgiving day. Norman, she said, is a native of Portland, 20 years of age, a graduate of Franklin high school. A brother, Clarence, is an employee in the Bremerton navy yard.

Wilbur C. Harvey, George W. Dowling -- Both were employed on the dredge Columbia at Wake. Neither has relatives in Portland, but both planned to marry Portland women upon their return, scheduled for next month, to the mainland.

Dowling's fiancee requested that her name be withheld. She said Dowling was a fireman on the Columbia, that he had worked on dredges in this vicinity for many years. He has a sister living in Spokane.

Harvey planned to marry Margaret Woods, elevator operator in the Lewis building, she reported, opening a locket containing his picture.

Joseph P. Donovan -- Mrs. Donovan, 1929 N. E. Ainsworth street, was happy to learn of the presence of her husband's name on the list, as well as those of others on the dredge crew whom she knew. Donovan, 64, has lived two years in Portland, and the Donovans had just bought their home here when he left to work at Wake.

John Hornyak -- A fireman on the dredge Columbia, Hornyak, 32, is a native of Hartford, Conn., where relatives reside. His wife is living with her mother, Mrs. A. G. Fry, 2331 S. E. Yamhill street. At the end of a six-year period of service in the navy in 1937, Hornyak and the Portland girl were married and lived in Hartford until two years ago, when they came here and Hornyak became an employee of Swift & Co. He went to Wake island last April.

Elmer Mackie -- For five years before he went to Wake island to work as third mate on the Columbia, Mackie, 29, was an employee on the government dredge Multnomah in the Columbia river. Several years earlier he was a member of the Oregon national guard. He is the son of Mr. and Mrs. William P. Mackie, 3820 N Gantenbein avenue, and a brother of William P. and Lillian Mackie, both living with their parents, and Mrs. Eileen Van Beek, 7039 N. Montana avenue.

Claude B. Howes -- His family, living at 238 N Fargo street, last heard from him in a letter written on Wake December 1 and received here December 8, although they have been assured by the dredging company that he was probably a prisoner and alive. Howes, 47, who has made his home in Portland for21 years, was formerly employed as a welder by the Port of Portland. Awaiting further news of him are his wife, Cora Kay, and two daughters, Florence and Virginia.