|

Prisoners of War in the Philippine Islands Military Intelligence Division Report September 20, 1944 |

| Main | Camp Lists | About Us |

PRISONERS OF WARIN THEPHILIPPINE ISLANDS20 September 1944Prepared by MIDWashington, D.C.DISTRIBUTION

CONTENTS

I. INITIAL PHASE I. INITIAL PHASE The surrender of our forces on Bataan on April 9, 1942, and the subsequent surrender of Corregidor, with the accompanying order for our forces to surrender throughout the Philippines, brought on the most ruthless mass treatment of our prisoners of war in Japanese hands. This treatment was apparently based upon a fixed policy of indifference, debilitation and humiliation. On many occasions the treatment of those captured was a matter of revenge. At Fort Drum for instance, the officers and men were subjected to 48 hours of "hazing" after their surrender, during which time they were not allowed to sit down or to sleep or to have water or food. It is reported that this was due to the fact that Fort Drum had dropped a 14-inch shell amidst a large group of Japanese on Bataan, killing a high-ranking Japanese officer whose brother was still in Manila and who ordered this special treatment of the Fort Drum contingent. The forces both on Bataan and Corregidor were subjected to bombardment for hours after their terms of surrender had been accepted by the Japanese. The "Death March" from Bataan to San Fernando was another form of punishment on the part of the Japanese. The Japanese have tried to counteract our accounts of the crowding and maltreatment of our POW in their hands by publishing accounts of how Japanese citizens were crowded and underfed at the time of and just prior to the outbreak of hostilities, particularly in Java and Singapore. The Japanese Military in the Philippine Islands, as elsewhere in the field, showed little evidence of a sense of responsibility for the lives and welfare of the prisoners. The survivors of Bataan were informed that they would be treated as "captives." After the fall of Corregidor they were raised to the status of prisoners of war, but their lot showed small signs of improvement. Camp Commanders and their subordinate officers paid little attention to the prisoners and left their welfare to uncouth privates and non-commissioned officers who gave them their orders and made them salute and bow to all Japanese soldiers above the rank of private, regardless of whether they (the POW) were generals or privates. Japanese generals and other high-ranking officers visited the camps but no apparent improvements were initiated following such visits. However, POW above the rank of Lt. Colonels were soon relieved from this treatment by being sent to Formosa where they were better cared for. Conditions of the POW in the Philippines has greatly improved particularly since the arrival of the Red Cross packages and our government's official protest to the atrocities committed against our POW. This showed that, contrary to the Japanese policy, we had a real interest in the welfare of our prisoners in Japan's hands. The trend of the war also is having a certain effect on their treatment. Apparently, as long as the Army in the field exercise control of the POW, there can be little hope of much improvement, unless their policy is changed. II. RELIEF TO POW IN THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS The International Red Cross has not been permitted to visit POW Camps in the Philippine Islands or any other POW Camp south of Canton, as they are considered by the Japanese to be in the zone of battle. The Red Cross which operated in the Philippines before Pearl Harbor was under the American Red Cross, and as a result of this, the Japanese, when they took control, refused to permit it to function. In May 1942, the newly organized Philippine Red Cross was given the existing Red Cross credits of money and food stocks, but the Japanese would not let the International Red Cross recognize it. This has hindered the Philippine organization as it has no official status and the work done is under the Japanese Red Cross guidance. Even so, the Filipino Red Cross was refused entry five times to Cabanatuan when it came with truck loads of supplies for the POWs. There is other evidence that the work of the Philippine Red Cross has been limited because of Japanese supervision. In the fall of 1942, the first consignment of Red Cross food packages arrived in time to save the lives of many POWs. In most cases, the Japs withheld rice and other rations while Red Cross supplies lasted. From February to July 1944, the YMCA had permission to send books, athletic equipment, musical instruments, seeds , gardening and carpentry tools into the Philippine POW Camps. However, these activities were greatly hampered due to lack of shipping space, communications, and other obstacles. At the present time, the Japanese do not permit either the YMCA or the International Red Cross to be active in the Philippines. United States Financial Assistance. The Swiss Minister at Tokyo was authorized by the Department of State in a telegram dated 19 August 1944, to arrange for financial relief or assistance for American POW in the Philippine Islands at the rate of 20 pesos (the equivalent of $10.00) monthly for each prisoner. Officers were to share equally in this relief. Negotiations are now in progress to fulfill this request on the basis of 9,000 American POW in the Philippine Islands, as reported by Tokyo. It was desired that these sums of money should be expended on a group basis rather than to individuals, with the advice and cooperation of Camp committees, leaders or spokesmen. Priority was to be given to the purchase and distribution of medical and food supplies. Such supplies were to be distributed in addition to, and not in lieu of, those regularly supplied by the Japanese. A monthly telegraphic report was desired, showing the number of Army, Navy, and Marine Corps who benefited, and the total amount expended. III. INFRACTIONS OF THE GENEVA CONVENTION Japanese Policy The outstanding infraction of the Geneva Convention regarding the treatment of Prisoners of War was the announced policy of the Japanese that they would treat the soldiers captured in the Philippines Islands as captives rather than as prisoners of war. They carried this out by under-feeding them, over-marching them, under-clothing them, beating them, and executing them at the slightest provocation. The POW were given practically no food or water during the first week of captivity, and a minimum of rice, soup, and water rations thereafter. Prisoners were denied all fruit even though it was everywhere and rotted on the ground near some of the camps. The Japanese distributed one each of certain items in order to be able to say that their POW had been fed eggs, fruits, and other foods. As a result of Japanese treatment, hover, during the first months of imprisonment, our men died at the rate of 30 to 50 per day. For nearly a year they were not allowed to write, and no new reading material was allowed into the camps, with the exception of a few propaganda newspapers proclaiming the Japanese Naval victories. During the past two years the Government of the United States has on numerous occasions brought to the attention of the Japanese Government, through the Swiss Government, reports of neglect and mistreatment of American prisoners of war and civilian internees in Japanese hands. In Secretary of State Hull's protest of 27 Jan 1944, 89 violations were directly attributed to the Japanese. Domei reported from Tokyo on February 5, that Sado Iguchi, Spokesman for the Board of Information, has stated that the information published in this country and Great Britain concerning Japanese mistreatment and neglect of prisoners of war is without foundation. While the question of the atrocities apparently is being considered by the Japanese as "belonging to the past," the Department of Stated is continuing to exert pressure through the Swiss Government to get POW conditions ameliorated. Target Areas According to Article 7 of the Geneva Convention (Evacuation from Combat Zones), Prisoners of War should not be kept near, or made to work in, combat areas. While the two Main Camps, Cabanatuan and the Davao Penal Colony are not in target areas, the various work details in the ports and working on the airfields are. Our government has protested the Japanese policy of segregating our prisoners near or on military objectives. IV. POW FIGURES Original Number of POW Total Figures: According to the official casualty reports, the Japanese captured at least 50,000 of the American and Filipino fighting forces in the Philippines. Approximately 17,000 were American soldiers, sailors and marines; 12,000 were Filipino Scouts, and 21,000 members of the Philippine Commonwealth Army. A high percentage of the POW died due to Japanese treatment, or rather, lack of proper treatment. During the first half year of captivity about 5,000, or nearly 30%, of the Americans died, while an estimated 27,000, or 80%, of the Filipinos died. April 1944 Estimate Since Sept. 1942, the tendency was to send more and more skilled POW to work in Japan. Some were sent to Formosa and some to Southeast Asia. By April 1944, the estimated number of POW in the Philippine Islands had been reduced to 7,000: and the remaining 1,200 at various work camps mostly around Manila. In July and August 1944, transfers to and from Mindanao were reported. It appears that in June, most of the able-bodied prisoners were moved north from Davao Penal Colony, leaving only the sick and feeble there. Later some 800 were brought to work on the airfields. These were reported to have been transferred north by the end of August. In July, some 1200 British and Australians were reported to have come to Manila from Singapore. In the second week of September our submarines reported having sunk some Japanese transports north-northwest of Luzon from which at least 60 to 75 Australians were rescued. In September 1944, the number of American POW reported by the Swiss from Tokyo was 5,700 in Japan, 1,700 dead and 9,000 in the Philippines -- a total of 16,400. This total approximates the MIS-X total of April 1944, of 7,000 in the Philippines and 10,000 in other Japanese-occupied territory. The P.M.G. totals in April concurred with the estimate of approximately 9,000 in the Philippines and 10,000 in Japanese-occupied territory, a total of some 19,000. This includes the unreported deaths in the Philippines. Evacuees from the Philippines declare that the number of POW who died there was nearer 5,000. Estimated total of POW in Philippine Islands as of Sept. 15, 1944: The Japanese have shown little interest in submitting accurate POW figures. Therefore, the total of 9,000 may be maintained by the Japanese in order to profit by the $10.00 expendable per POW. V. CORRESPONDENCE Five batches of mail, containing a total of 40,320 pieces, have come through Japanese hands from the Philippine Islands to the United States during the year Aug 1943 to Aug 1944. Most of these were postcards; many merely contained vital statistics for insurance purposes. Over half of the mail (24,915) came from two camps #1 and 3 at Cabanatuan. These camps contained about 3,500 POW during that period, but many of the personnel may have been moved to Japan, and the other POW who replaced them may have written also, which no doubt helped to swell the grand total of cards from the Cabanatuan Camps. In the last mail, letters from the Cabanatuan Camps averaged about one letter per person for the half year period. The second largest number of letters received during the year was from Davao -- 5,700 cards. There were nearly 2,000 POW at Davao during that period but in the last mail only 10 cards from 8 POW were received. This restriction may have been caused by disciplinary measures because of the several escapes from this camp. Another reason may have been the sinking of shipping from Davao. During the first year, Apr 1942 to Apr 1943, contrary to the rules of the Geneva Convention, POW in the Philippine Islands were not allowed to send any mail out of the camps. The first mail received from the POW in the Philippines reached the United States prior to Aug 1943, and contained 3,675 letters from 21 different camps, numbered from 1 to 17, plus numbered 10A, 10B, 10C, and 10D. Most of these camps are near Manila. Camp #6 contained only one civilian and was not heard from again; neither was Camp #14, containing 6 POW. Since December 1943, no mail has been received from Camps #11, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17. The second consignment of mail, which came in Sep 1943, was larger, containing nearly 8,000 pieces; 4,460 from Cabanatuan and 1,851 from Davao, indicating a "letter" from each POW. The third batch totaled only 746 and might be considered as just an overflow of the second. The fourth batch, received a month later, was the largest: 27,405. From Cabanatuan alone came over 13,000 cards, with 3,660 from Davao. The latest shipment received 27 July 1944, totaled 5,599 cards and 11 letters from 5,130 American POW in the Philippine Islands. Nearly all this mail is undated, but letters from other camps, received at the same time, were dated from September 1943 to March 1944. The mail contained many single card acknowledgments of packages received and also requests for additional insurance. Cablegrams brought some comfort to the POW, for at least 275 acknowledgments were observed in the mail. This is a small percent considering there are about 7,000 American POW in the Philippine Islands, but it is very likely that many more cablegrams were received but the acknowledgments were not included in the July mail. Cablegrams can be sent once a year by the next-of-kin, except in case of an emergency when more than once can be sent. The table on the following page breaks down the origin of these letters as to Camps and personnel. A 50-word message card is still being used, with one line for the writer to underscore as to whether his health is excellent, good, fair, or poor. The camp rules permit POW to write such a card every three months. However, no definite schedule for delivery of such mail has been established. There is no limit on the number of letters going to the Islands but they must not exceed 25 words including the signature and must be typed or printed in capital letters. The Red Cross has three form letters which can be used. The first is the ordinary postage-free letter. The second in an airmail special called Form No. 11, and the third is a simplified postcard available at local Red Cross Chapters. In addition to these is the Provost Marshall General's Form No. 111 which is recommended for more reliable delivery. TABULATION OF MAIL DATED FROM SEP 1943 THROUGH MAR 1944, RECEIVED 27 JULY 1944, BY U.S. RESIDENTS FROM AMERICAN POWS IN THE P.I.

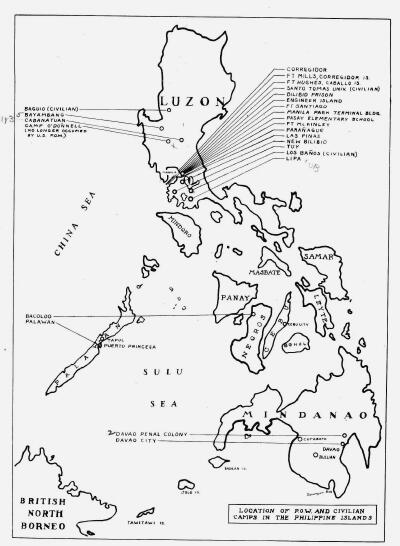

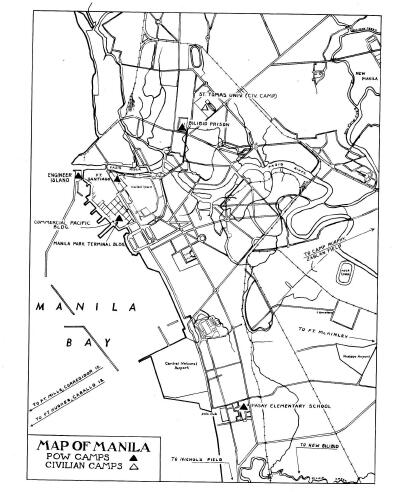

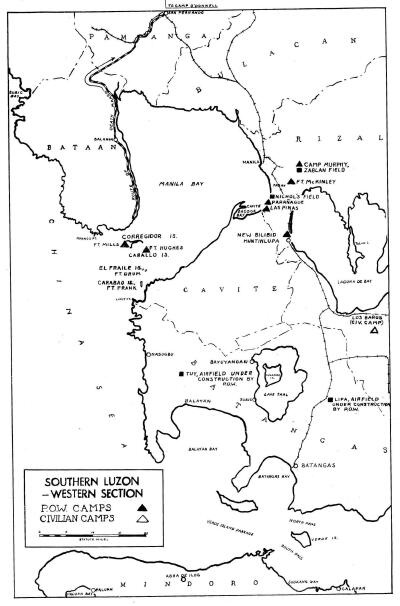

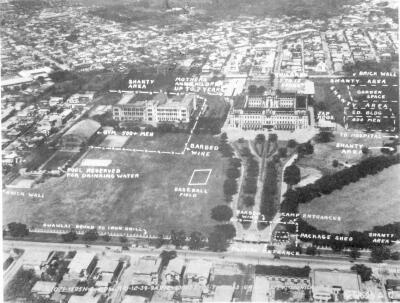

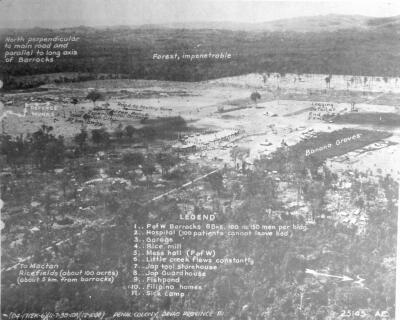

VI. INDIVIDUAL CAMPS IN THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS A. North of Manila 1. O'Donnell -- Terminal of the "Death March": After the surrender at Bataan on April 9, 1942, Americans and Filipinos were marched, regardless of their condition, practically without food or water, to San Fernando, a road distance of approximately 140 miles. From there they were taken in box cars to Camp O'Donnell in Tarlac Province, Luzon. The march lasted a week. During this "Death March" (for the route see illustration), many were forced to go barefoot and hatless over the hot rocky roads. They were actively prevented from getting water, were only fed once, and given little rest. Those who fell by the wayside, or who were observed trying to drink water or get food from the natives, were either clubbed, shot or bayoneted. Most of those who succeeded in getting water from carabao wallows came down with dysentery. Many got malaria and other diseases. Along the road they were laughed at, struck, beaten and spit upon by passing Jap soldiers and officers. Others, thirsty and crazed for want of food, went insane and were killed by the Japanese. Filipinos, however, took every opportunity to throw the prisoners food and cigarettes. Cans of drinking water were left on the highways near the road toward the end of the march and, if not turned over by the Japanese, were drunk from by the Americans. The Japanese tortured their prisoners in other minor ways, such as preparing food near their halting place and then, on some pretext of non-cooperation, taking it away and marching them on. All POW, from privates to generals, were required to salute all Japanese, from privates, up. The prisoners were marched to San Fernando in successive groups ranging from about 500 to 1,500. Each group was only fed once, a saucerful of rice, some on the third day, others not until the seventh. Groups of 1,500 Americans and Filipinos were forced into the same barbed wire enclosure built to accommodate the 500 size groups. As most of the prisoners had diarrhea and dysentery, contracted from the polluted water they drank along the way, human defecations soon covered the whole area, if it was not already so covered by the previous groups. For this reason, and due to the over-crowding, to even sit up in a comfortable position was hopeless. Sleep was "impossible." The stench was terrible. Two days were spent at one of these temporary camps before marching on to San Fernando. There they were put into box cars which might have accommodated 25 to 50 persons. Over one hundred POWs were put into each and the doors locked. There were no sanitary arrangements. The situation was "indescribable." At Capiz, Tarlac Province, the prisoners were unloaded and put into another temporary open camp in the burning sun (as usual) for several hours while they were counted. Many were beaten up for no apparent reason. Then, placed in columns of four, they were marched to O'Donnell Prison Camp, an old Filipino Army Cadre. Of the ten thousand Americans who surrendered on Bataan, many died enroute and the health of the others was so undermined that they died at the rate of fifty a day, on the starvation diet given at the unhealthy Camp O’Donnell. Over 2,000 Americans died of disease and undernourishment before the remainder were moved to Cabanatuan in July 1942. Finding sufficient able-bodied men to bury the dead was a problem. Often, a high percentage of the burial detail would be thrown into the common graves because they had died from overwork. Sometimes exhausted men were buried before they were actually dead. 2. Cabanatuan -- Camp No. 1 and Camp No. 3. Route: The 7,000 Americans from Corregidor fared better. However, they were crowded into a small open area for a week prior to going by boat to Manila, and were made to wade ashore before being paraded through the streets -- in order to make a more defeated impression. After a short stay at Old Bilibid prison, they were packed into freight cars and sent to Cabanatuan. The surviving Americans from O'Donnell soon joined them there. They brought up the death rate at Cabanatuan to about 50 a day. Two camps were formed at Cabanatuan. No. 1, where most of the officers were located -- about 9 miles from the city, and No. 3, about 6 miles from Cabanatuan. The camps lacked the proper and necessary sanitary arrangements and the dead were left lying around. Even after they had been removed, the nauseating odor from the nearly graveyard and its shallow graves affected the surviving POW. Attempts to escape or to use the black market to get in food were severely punished, usually by torture and death. Innocent associates of the escapers were penalized. In one case when a man escaped while on a work detail, five American POW were selected summarily and shot. The camps were divided into "shooting squads" of ten men each, upon the escape of anyone or more, the rest of the squad were to be shot. Medical supplies offered by the Philippines Red Cross were refused entry on five different occasions. The hospital was just a place to die. Number of POW. In September 1942, groups were selected to go to Japan. About 5,000 Americans were sent there within a year. One thousand were sent to Davao. That left about 6,000 in Cabanatuan, of which about 2,000 were too sick to survive long. In April 1944, due to the death rate, withdrawals, shipments to Japan and elsewhere, it was estimated that there were about 3,500 POW at Cabanatuan. At the end of June 1944, a large group of American and Australian POW arrived in Manila reportedly from Davao and Singapore. The bulk of these were said to have been confined to Cabanatuan. This raised the number to about 4,700. That was reduced to 4,000 when the Australians were shipped to Japan in September '44. Food consists of rice, native vegetables and carabao meat, poorly prepared and in insufficient quantities. Practically no meat was issued for the first 6 months after the fall of Bataan. The diet has not varied much except for the occasional Red Cross packages brought by the Gripsholm which were distributed to the POW in Davao from Christmas 1942, to Feb '43, and from Thanksgiving to Christmas late in 1943. No further arrangements for food shipments have been approved by the Japanese. However, late in 1942, Philippine women obtained permission to open canteens for the POW at Cabanatuan as well as at Santo Tomas and sold canned products at reasonable prices. The items sold consisted chiefly of pork and beans, peanut butter, jellies and jams. In this way, Americans with a little money could obtain the saccharine missing in Oriental diet. At Davao, they had an insufficiently stocked canteen operated by the POWs. Clothing. Meagre quantities have been provided by the Japanese authorities. Many of the men at the camp are barefooted and wearing loin cloths only. Their feet become sore and infected from going barefooted while working on work details. Work. All prisoners are forced to perform labor. Officers and men work from 6:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. and 1:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. on a farm. They must walk two miles to the farm from the barracks. Pay. Officers receive pesos 25 per month ($12.50). They have been receiving this sum since January 1943 only. Miscellaneous reports from letters of enlisted men state that they are now being paid varying amounts, ranging from 10 sen to 30 sen per day. This constitutes a daily wage of 3 to 9 American cents. Financial assistance to POW on the same basis of $10.00 per man per month has been requested by the State Department. Recreation. The men are allowed to use spare time as they please. They have organized dramatic and entertainment groups but they are usually too fatigued after the day's work to take part in active sports. A card from a POW states that he had been acting as Master of Ceremony at the camp show twice a week. POW mail refers to a library and books at Cabanatuan which has made it possible for POW to study Spanish and mathematics. One officer reported he had a small garden. 3. Bayambang is located on Luzon Island about 20 miles south of Lingayan Gulf and about 40 miles NE of Cabanatuan. POW are reported to be working here either on agricultural projects of airfields or both. No further details as to this camp have been reported. B. Manila Area. POW have been imprisoned in this area in at least seven different locations. 1. Old Bilibid Prison was first used as a transfer center and for the last year or so, now as a POW hospital. POW cases from the various camps and work details are sent here. 2. Fort Santiago, with its old prison cells, is said to be used as a punishment and torture prison. 3. Several hundred POW are housed in the warehouse of the Commercial Pacific Building, between Piers 5 and 7. 4. The Manila Park Terminal Building is at the end of Pier 7 and right near the Commercial Pacific Building. The POW from here may have been moved to the Commercial Pacific Building. 5. Engineer Island -- at the mouth of the Pasig River; was used to house POW working on the docks. 6. Pasay Elementary School -- This camp on Park Avenue, about 300 yards east of the point where F. B. Harrison (Street) passes the entrance of the Manila Polo Club Field in Pasay, just south of Manila. The number of prisoners was between 150 and 400. They worked at Nichols and Neilson Airfields and were marched there every day at 0745 and returned at 1715. They received poor treatment, and were under-fed; lacked clothes; and were poorly paid. This camp may have been moved nearer work elsewhere. 7. Fort McKinley -- Some POWs and internees reported here ( C. Work Details Beyond Manila: 1. At Nichols Field (probably completed by now). 2. At Camp Murphy and Zablan Field. 3. At Parañaque and Las Piñas. 4. At Fort Mills on Corregidor. 5. At Fort Hughes on Caballo Island. 6. At Tuy Airfield in Batangas. 7. At Lipa Airfield in Batangas. 8. New Bilibid Prison at Mintinlupa, Laguna de Bay Rizal. Quantity held here unknown, possibly Filipinos. ON 7 April, 500 reportedly shipped from this camp to Davao, and 60 escaped 25 July 1944. 9. Nasugby in Batangas is indicated because it was there that a group of POW were captured at Fort Drum and made to work on the docks without hats, food or water, for two days in the broiling sun. At the end of that time, some of the men were drinking salt water and were semi-delirious. They were then marched by the Japanese through the town. During and following the "Victory Parade" many of the POW collapsed. To show the contrast, they were followed by well fed and rested Jap troops. After the parade our men were fed for the first time, and sparingly thereafter. So great was their hunger that death seemed preferable to two of these prisoners who thereupon made their escape. One of them reached Australia in safety. 10. Limay, Bataan. Following the fall of Bataan and Corregidor, a group of about 200 American soldiers convalescing from wounds and disease were taken from a hospital to collect scrap metal for about two hours a day on Bataan. They were camped near the town of Limay to which they were permitted to go under Japanese guard. The American officer who was put in charge of this group under the orders and surveillance of the Japanese became very friendly with the Jap Camp Commander who treated him very well. They took over a one-room house in which to live. There were two mattresses in it, a "Beauty Rest" and a thin one. The Japanese "pulled his rank" to get the thin one, much to the pleasure of the American. This preference indicates that the Japanese are not particularly conscious of inflicting hardships on POW by supplying them with the thin mattresses customary in Japan. Because of his friendship with the Jap Camp Commander, the American was permitted to visit his wife, interned at Los Baños, under escort. He is said to have been allowed to stay in the camp for three or four hours on his first trip, and later on was able to stay over-night. He was permitted to visit his wife in the camp about ten times over a period of six months. Such kindnesses on the part of the Japanese are rare, but have occurred elsewhere. On one occasion the American was permitted to go hunting, with the Japanese, who furnished him with a shot gun. The Japanese carried sub-machine guns to protect themselves from the guerrillas. D. Civilian Internment Camps There are at present three civilian internment camps in the Philippine Islands, all located on Luzon. It is not usual to include internment centers with prisoner of war camp reports, but in this instance, it is pertinent to do so, not only as targets to avoid, but because they contain Army and Navy nurses. 1. Santo Tomas (See Manila map) The buildings and grounds of this institution contain some 4,500 internees including 75 Army nurses. For buildings and camp layout, see photograph. The last 500 internees were recently added when all American members of religious organizations, nuns and priests were brought there in an effort to eliminate the possibility of cooperation between the Americans and the Filipinos. This still further crowded the limited capacities. The inmates had Filipinos build shacks for them which were parked around the grounds as indicated on the photograph. There are about 600 of these. They afford a small degree of privacy to the occupants. Men and older children live in them. Women must be inside the main buildings by 1930. Parcels are delivered for the internees in the compound near the main gate. After the Filipinos have left and the parcels have been inspected, the internees are allowed in to get them. Thus contact between Filipinos and whites in avoided as much as possible. This is the reason for the Swawlai matting on the iron fence. There are, however, many "incidental" holes in this coverage. On the whole, Japanese treatment of internees has been reasonable, in contrast to the treatment of POW. 2. Los Baños Camp Los Baños Camp, some 65 miles southeast of Manila, is about 5 miles from Laguna de Bay (see map). It was formerly the Agricultural School of the University of the Philippines. In May 1942, in order to make more room at Santo Tomas, 800 of the ablest-bodied men were moved to Los Baños. Eleven Navy nurses voluntarily went there to help run the hospital. At the time of the American landings on Guadalcanal (August 1942) some of the younger men escaped and joined the guerrillas. More were going to do so but one of the escapees advised them not to, because of the difficulties of survival. The Japanese reaction to this was to put the camp on a stricter military basis and to put up an outer 8-strand barbed wire fence, to keep out the guerrillas. The location of the camp near the foothills of a mountain makes it healthy, but the reported addition of 300 internees from Davao strains the facilities of the camp and makes it overcrowded. Certain internees from Los Baños camp have been moved to Fort McKinley where a major ammunition dump for central Luzon is maintained. The State Department has protested such actions as contrary to Article 9 of the Geneva Convention, and has requested removal of the internees. 3. Camp Holmes, in the Bontoc Mountains, off the NE end of Trinidad Valley, seven miles north of Baguio (see map) contains some 500 civilians. Its location is one of the healthiest in the Philippines Islands. E. Bacalod, Negros (See map) Ten non-commissioned officers and enlisted men were brought here on May 13, 1942, from Bataan to act as truck drivers. Often they had to drive under fire into guerrilla-held territory. One of them escaped on April 1943, and seven more successfully escaped on 4 July '43, leaving two of their number behind. As their services were needed, those remaining were not severely punished; a stricter watch was kept over them, and dieting restrictions were temporarily increased. 1. Duties: Their principal duties were driving trucks, hauling ammunition and supplies, and making repairs. They drove International G.I. Chevrolets, 1935 Fords, and Chevrolets converted into ammunition trucks. Also one 21/2 ton "Jimmy." 2. Living Conditions: They lived in Japanese soldiers' quarters and had much the same food. This being insufficient they had to supplement it with food bought from the Filipinos, which usually had to be smuggled in to them. Their usual food was fish and rice, supplemented by vegetables and whatever other food supplies the Japs had. 3. Pay: The maximum wages paid were 25 pesos ($12.50), which was reduced to 3 pesos per month ($1.50). 4. Treatment: At first not too bad. With successive new commanders, treatment became worse -- less food, greater restrictions, and harsher punishments for misunderstanding, etc. After the first of the eight escaped in April 1943, all freedom was taken away. (a) They were told they would be treated as POW -- their names and general locations were sent to parents in the United States (one year after capture!). (b) They were informed that they had been treated very kindly, and if the treatment seemed harsh, it was the same as that of Japanese soldiers who are used to being slapped and kicked around. Besides which, the Japanese said they felt they were giving our people the same as had been given to the Jap POWs abroad. The men were required to raise their left hand and swear that they would not attempt to escape under any circumstances. That was early in June 1943. In July, conditions for them became intolerable and they escaped. Two American prisoners were left behind. Local circumstances prevented the remaining two from leaving at time. No word as to any serious reprisals has been heard. F. Puerta Princesa, Palawan (See map) 1. Location and Personnel In September 1942, approximately 400 American POW, mostly marines, were transferred from Cabanatuan to Puerto Princesa on Palawan. They were lodged in the old Philippine Constabular Barracks, surrounded by a double row of barbed wire. Earlier reports indicated that they might have been kept at the Iwahig Penal Colony, inland across the Bay from Puerta Princesa, but this has been refuted by returned personnel. Due to transfers north to Manila, and to deaths, only about 300 POW remain in Puerta Princesa. 2. Type of Work The POW have been working on an airfield (enclosed by barbed wire) in the vicinity, which no outsiders are allowed to approach -- not even Filipinos. The airfield, Canigaran, is reported to be of rock construction, and capable of functioning in the raining season. The POW here are being used to improve the roads between Puerta Princesa and Tapul. 3. Escapes Shortly after arriving at Puerta Princesa, eight or ten of the POW escaped, while on a work detail, by walking into the nearby forest. In February 1943, two groups of two men each broke out from their barracks. The first group was recaptured, tortured, and finally killed by the Japanese. The second two were successful. 4. Food At the time of their escape, the POW were being fed rice with a few vegetables, but all in insufficient quantities. No bedding was issued and the POW slept on dirt or cement floors. A very few had blankets of their own. Morale was low and the men did not care what happened. G. Davao Area 1. Davao Penal Colony At Davao Penal Colony, conditions were better than at Cabanatuan. There was a mess hall; food was more plentiful and varied; and the hospital had more medicines. It was not long, however, before conditions became worse. The arrival of some Red Cross food packages in Feb ‘43 saved many lives. A party of ten had sufficient strength to escape into the almost impenetrable jungle in April 1943. At that time, the guards were doubled from 100 to 200 and no immediate punishments were given as an attack by the guerrillas to free the rest was expected. In October, two more men escaped and twelve were men were reported confined for fifteen days as a result. In April 1944, a report was received that 25 POW had been executed in retaliation for those escapes. More restrictions were placed on the prisoners who were forbidden to take canteens to work with them and could not wear long trousers, shoes, or jackets. Apparently, this was to prevent the men from concealing any supplies in their clothing and also to make them more exposed to the perils of the jungle if they tried to escape in shorts only. Men and officers were assigned various work details such as: lumbering, planting rice, plowing, collecting fruits, coffee and other crops; as well as making repairs and building defense works. Their diet consisted of rice for breakfast with reduced amounts of comotes for lunch and supper. Of the thousand that arrived there from Luzon, about half of them were too sick to work. The POW were joined at Davao by another 1,000 who had been kept elsewhere in Mindanao. They were in better condition but were soon reduced by illness, debilitation and lack of proper diet. Although there was plenty of quinine in camp, 99 percent of the prisoners had malaria. Prisoners are required to work for a half day while having attacks of malaria; after recovery on the third day, they must report for full duty. Of the 1,961 prisoners in the Colony in April 1944, 50 were completely bedridden and 500 unable to work. Upon the protest of two colonels to Major Maida, the Japanese Camp Commander, regarding violations of the Geneva Convention, Maida replied, "We treat you like we wish." On 6 June, the 1,200 POW confined in the Davao Penal Colony were bound, blindfolded and placed on board a ship in Davao harbor where it remained until it sailed 12 June. The ship was so crowded that only one in three could lie down. 2. Work details area Davao City After the POW first arrived at Davao, a certain number were separated from those bound for the Penal Colony and were used to drive trucks around Manila. Later some 800 who had been shipped from Manila were reported working on Licanan (Likanan) field while 50 worked on the Matina airfield. These work details were later reported shipped north after the completion of the fields. Apparently most of the able-bodied POWs have been shipped north from the Davao area. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||