|

American Prisoners of War in the Philippines Office of the Provost Marshal General Report November 19, 1945 An account of the fate of American prisoners of war from the time they were captured until they were established in fairly permanent camps |

| Main | Camp Lists | About Us |

REPORT ON AMERICAN PRISONERS OF WARINTERNED BY THE JAPANESEIN THE PHILIPPINES |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

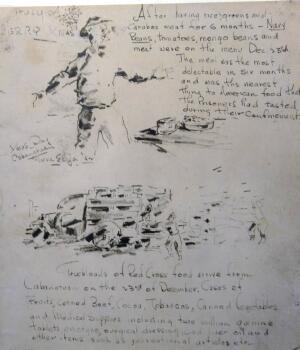

Arrival of first

Red Cross food

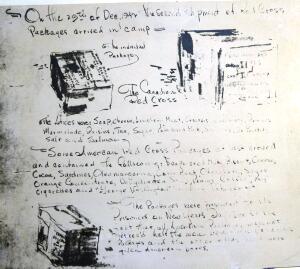

"Xmas Day, Cabanatuan. Nueva Ecija""After having rice, greens and carabao meat for 6 months -- Navy Beans, tomatoes, mongo beans and meat were on menu Dec 23rd. The meal was the most delectable in six months and was the nearest thing to American food that the Prisoners had tasted during their confinement." "Truckloads of Red Cross food arrive from Cabanatuan on the 23rd of December. Cases of Fruits, Corned Beef, Cocoa, Tobaccos, Canned Vegetables and Medical Supplies including two million quinine tablets, emetyne, surgical dressing, cod liver oil and other items such as recreational articles etc." |

This year, too, the Americans were allowed to maintain a commissary, thus enabling them to supplement the monotonous rice diet with fresh vegetables, such as bananas, peanuts, and a few limes and cocoanuts, which they purchased from the Filipinos. Through the commissary, too, they could occasionally obtain small quantities of tobacco.

Thus, what with the Red Cross packages, the few products from the camp farm, the increase, small though it was, of the rations issued by the Japanese, as well as because officers and men alike were receiving some pay, and could thus buy some additional food from the commissary, the year 1943 -- the first half, at least -- proved to be the best, so far as food was concerned, of all the three years at Cabanatuan. The improvement in conditions was evidenced by a notable decline in the death rate among the prisoners, as well as by the fact that many of the men who had been hospitalized all during the last months of 1942 now began to recover their health sufficiently to permit them to be assigned to work details.

Toward the latter part of the year, however, the situation again worsened. The rice issue was cut approximately one-third. Food supplies were still further curtailed by the fact that, because of the scarcity of commodities and the resulting price inflation, the commissary ceased to function in the latter months of the year. As an example of the extent to which prices of food had increased we may cite the fact that a canteen cup of peanuts which could be purchased at the commissary in the early months of 1943 for 50 centavos, toward the end of the year brought approximately 5 pesos. The number of men suffering from diseases of various sorts, as well as from malnutrition again rose, and, despite all the protests lodged with them by the American officials, the Japanese did nothing to alleviate the situation. The Filipino Red Cross and other charitable organizations in Manila made several attempts to obtain permission from Japanese headquarters to supply the camps with the food and medical supplies they so badly needed, but this permission was never granted.

In the urgency of the situation the men had recourse to all kinds of tricks and deceptive devices in their efforts to get additional food. The set traps to catch birds, stole seeds from the Japanese, and planted little gardens all over the area. An "underground" system was devised by the Americans and Filipinos, to facilitate the smuggling of small amounts of food and medicines into the camps. By dint of exercising considerable ingenuity the Americans and Filipinos were able to continue this "underground" quite successfully until the summer of 1944, when approximately sixteen Americans and an unknown number of Filipinos were caught carrying on these operations. The Americans were severely beaten and sentenced to confinement for a long period of time for this infraction of Japanese regulations. The fate of the Filipinos is not known, but it is presumed that they were killed.

Some few of the men were able to secure extra food while they were on outside work details. For example, the guards set over the men assigned to the wood-chopping detail occasionally permitted their charges to trap and cook iguanas and wild carabao. Others, so great was their need for food, occasionally stole a few vegetables from the farm, even though they ran the risk of being severely beaten or even shot, for so doing. Some of the prisoners who drove trucks for the Japanese were able to smuggle small amounts of food into the camp, and thus managed to weather this difficult period more successfully than did others who were not so fortunate.

Once again the Red Cross packages, though fewer in number than those received in 1942, arrived just in time to save many lives. Approximately three of these individual Red Cross boxes were issued to each man in the first days of 1944. During this year the food situation became increasingly more critical. The rice issue was cut down several times in the course of the year, almost none of the vegetables grown on the farm were allotted to the prisoners, and the commissary was now closed, and thus cutting the men off from one more avenue for securing food.

Now they were driven to catching or trapping birds, cats, dogs and iguanas in order to have food for their starving bodies. The number of thefts of products from the farm increased every day. Toward October, when the last of the details were being evacuated to Japan, the men stole and pilfered from the camp farm and gardens all the food they could possibly eat, regardless of the consequences.

Some extracts from a diary kept by one of the American prisoners of war give a vivid picture of the terrible food conditions that prevailed at Cabanatuan during the latter half of this year:

20 May 1944: We had dog meat day before yesterday. Sure tasted good. Any meat tastes good these days.By comparison, the Japanese ate very well during 1944. They raised over one thousand ducks, several hundred chickens, and a few hundred pigs. Rice was still their main article of diet, but they had meat, vegetables and fruit in ample abundance to stave off starvation or any vitamin deficiencies among their own troops.

20 June 1944: One of the Japanese Dr's visited the hospital this week and promised Red Cross chow. He also asked our Dr's if they could use cats and dogs for meat...

4 August 1944: we are eating anything we can get our hands on. Some bean leaves and ochre leaves I ate didn't go so well, however. Some people ate corn stalks and the flowers, papaya trees, fried grub worms, dogs, cats, lizards, rats, frogs and roots of various kinds -- anything goes that can be chewed.

29 September 44: The commissary is just about closed. I doubt very much if anything else comes in. The last corn that came in cost 1,000 pesos a bushel.

Clothing. -- No clothing of any sort was issued to the prisoners of war in 1942. The garments they were wearing at the time they were captured soon began to wear out, particularly since for some time they were not able to keep it properly washed. The only possibility of getting new ones lay in stripping the clothing from the bodies of those who perished in the camp. Soon, therefore, the men found it necessary to patch and repair and otherwise take all possible measures to keep what clothes they had in wearable condition, if they were not be entirely naked.

The situation as regards clothing showed very little improvement in the next year. Clothing was issued only to those men who were picked for shipment to Japan, and their old clothes were collected and turned over to the camp supply officer, who had them deloused and distributed to the more needy among the prisoners who remained in the camp. One "G-string" was issued to each man every three months. Aside from these items the only clothing that came into the camp for distribution to the prisoners this year consisted of a few articles such as socks and handkerchiefs, which some charitable organizations smuggled in without the knowledge of the Japanese authorities. The prisoners were deprived of shoes early in 1943 by order of the Japanese general who inspected the camp, who decreed that from that time henceforward all Americans assigned to the farm and other work details would be compelled to go barefoot. This harsh decree was mitigated in only one instance by the Japanese camp commander, to permit members of the wood-chopping detail to wear shoes. No raincoats were ever issued to the men who had to work on the farm and in the fields all through the rainy season without any protection at all against the wind and rain.

The Japanese did issue several hundred pairs of shoes to the prisoners during 1944, but inasmuch as these were given only to the men who were being sent to Japan, it left the remaining prisoners at Cabanatuan no better shod than they had been before. The evacuees to Japan also received one suit of dungarees when they left. The only other item of clothing issued by the Japanese this year were a few "G-strings."

Medical Supplies. -- No medical supplies of any sort were issued to the prisoners during the first six months of their imprisonment, repeated requests of the American medical personnel for medicaments and other medical supplies being either consistently ignored or flatly refused by the Japanese. Some relief was obtained from small quantities of quinine, aspirin and sulfathiazole which a few of the prisoners carried with them on their march to the camp, but this supply was hopelessly inadequate to treat the malaria, dysentery, and other infectious diseases which decimated the numbers of the camp inmates. It was impossible to care for infected wounds properly, with no bandages, antiseptic ointments, or anything of the sort. Bandages were used over and over again until they practically rotted away. In view of these terrible conditions it is not surprising to learn that there were often as many as forty deaths in the camp in one day during 1942, and that the average mortality was thirty per day. By 31 December of that year about 2,500 Americans had perished at Cabanatuan from malaria, dysentery and other diseases, as well as from starvation.

Among the supplies received from the American Red Cross in 1942 was a fairly large quantity of emetine, carbazone and yatren for the patients with dysentery, as well as some anti-malarial remedies, sulfa drugs and a quantity of ointments of various kinds, dressings, bandages, etc. By practicing the most rigid economy the American physicians managed to make these supplies, limited as they were, last for three months. And even this small amount worked wonders, particularly in the treatment of the less serious cases. After the Red Cross supplies were exhausted, the Japanese for the remainder of the year issued sufficient quinine for the patients with malaria, although they gave the Americans little else in the way of medical supplies.

All things considered, the situation as regards medical supplies and the care of the sick was somewhat better in 1943 than it had been in 1942. Throughout 1943 the prisoners were given periodic shots of cholera, dysentery and typhoid serum. For, although the serum available was old, and was not regarded as having much prophylactic value, the American physicians in charge felt that it might possibly be better than no serum at all.

Again the supplies sent by the American Red Cross, which were received in the latter part of 1943, contained a fair amount of medicines and other medical supplies. The Japanese, however, did not turn all these supplies over to the Americans, in spite of the repeated protests made by the American Administrative Staff against this practice. Nevertheless...

Again the supplies sent by the American Red Cross, which were received in the latter part of 1943, contained a fair amount of medicines and other medical supplies. The Japanese, however, did not turn all these supplies over to the Americans, in spite of the repeated protests made by the American Administrative Staff against this practice. Nevertheless, even with the limited stores of drugs and supplies at their disposal, the American medical staff managed, by means of careful and judicious use of the drugs they had available, to keep diseases among the prisoners down to a surprisingly low minimum during 1944. The Japanese issued an ample amount of quinine for the malaria patients, and there were enough vitamin pills on hand to permit each man to have one pill every day for several months.

Dental supplies were woefully inadequate, and the methods of treatment used were make-shift. Fillings for cavities were made from silver pesos that have been brought into the camp unbeknownst to the Japanese. Few local anesthetics were available for extractions, and the equipment for grinding, as for extraction, was sketchy in the extreme, to say nothing of its painfulness. (One prisoner told of having several teeth drilled by means of a drill run by foot power, something on the order of a sewing machine.)

Work Details. -- Soon after the camp was occupied in June 1942, work details were organized by the administrative staff, and all prisoners except officers were assigned to one or another of them. It was the policy of the Japanese, at least in the beginning, not to force American officers to work, and they were so informed by the Japanese commandant. Later, however, in view of the fact that the quota of men available for the work details had been so reduced by reason of the large number of deaths as well as because of the increase in sickness -- approximately 70 per cent of the prisoners were suffering from the strain of the long, arduous campaign just ended, as well as from exposure, general mistreatment, and the complete change of diet -- the officers were told that it would be necessary for them to volunteer for service in the various details, if the camp was to operate at all. This they did very willingly.

The work details were employed, for the most part, in performing such tasks as were necessary for the smooth running of the camp, and in improving the living conditions of the prisoners, so far as possible. They were usually in charge of an American officer and a Japanese non-com, with one armed Japanese guard for approximately every ten men in the detail.

The main work detail in 1942 was the wood-chopping detail, made up of one hundred of the strongest and healthiest men in the camp, who went out every morning to the foothills of the Sierra Madras mountains to fell trees and cut the logs into cordwood, which was then loaded onto trucks and taken back to the camp to be used as firewood in the mess halls. These men were the only ones among the prisoners who were allowed outside the camp boundaries during the first few months. Another detail, also chosen from among the healthier men in the group, consisted of approximately two hundred officers and men whose job it was to carry rations and supplies from the Japanese area and distribution points to the American mess halls. Still another of the main details was the burial detail, which varied in size from day to day, depending on the number of men to be buried.

A large number of the prisoners was assigned to details whose chief task it was to render service of one kind or another to the Japanese. A small group was assigned to set as orderlies to the Japanese officers and non-coms. A few others were detailed to take care of the power plants that supplied electricity for the Japanese quarters. (There were no electric light facilities in the area occupied by the American prisoners of war.) Some of the prisoners the Japanese used to haul supplies by truck from the nearby town of Cabanatuan, and to keep the trucks that had been assigned to the camp in good repair. Each day, too, they called for other groups of prisoners to perform various menial tasks in the Japanese area, such as washing rice that was to be cooked for the Japanese, cleaning their barracks, feeding their chickens, washing their bath houses, and cleaning out the latrines.

In 1943 a more stringent policy was adopted by the Japanese with respect to work details. Because of the number of attempted escapes during 1942, a system of self-guard, so-called, was set up, whereby every ten men were placed in a shooting squad. If one of these men escaped, the other nine were shot. All prisoners were confined to their barracks at 9 P.M. and a guard posted at both ends of every building.

The farm was constantly increased in size, until by 1945 there were over five hundred acres under cultivation. In order that enough men might be available for the farm and other work details, the Japanese ordered that the population of the hospital should be reduced to approximately five hundred men. All the others were forced to work, no matter what their physical condition. As a result, many men who should have been in the hospital were forced to do heavy labor far beyond their strength.

The work detail for the farm alone was sometimes numbered as high as 2,000 men. They were divided into gangs of one hundred and assigned to various jobs, such as hoeing, digging, carrying water, planting, harvesting and tool-making. All officers were required to work, and chaplains and doctors were particularly singled out for the dirtier tasks.

During the months from January to August work on the farm was exceptionally heavy, and most of the men in the camp, sick or well, were assigned there. A daily detail of men carried water and took care of a herd of Brahma steers. Frequent beatings were administered to the men. They labored on the farm from 6 A.M. to 5 P.M., without shoes and with little or no clothing to protect them from the weather, and then either stood guard there during the night or, if allowed to go back to camp, had to carry five-gallon buckets of water long distances for irrigation purposes. Only the coming of the rainy season eliminated the necessity for these evening water-carrying details.

The latter part of the year the Japanese started to construct a new barbed wire fence. This made it necessary for the wood chopping detail to work longer and harder hours, cutting fence posts of a certain size and circumference. A fence detail was picked to erect a double fence 10 feet high, with a distance of approximately twenty feet between each fence. (The Japanese moved their guard and guardhouses in between the two fences.) Each fence consisted of ten strands of wire about one foot apart. An improved electric light system for the camp was installed during this period.

A large number of details left the camp this year, and the Japs concentrated those who remained in the area on the east side of the camp, and closed up the old hospital area. The shift involved moving many men, and all of it was carried out by the American prisoners. This type of work was always done at noon or during the rest period of the regular detail.

In January 1944 the Japanese commenced rebuilding an air field about two miles from the camp. Each day 500 to 1000 Americans, composed of both officers and men, would march barefoot through mud to this airfield. They worked all day with picks and shovels leveling off the field. Apparently this detail was less unruly than the farm detail, because the Jap guards did not molest the men during working hours. The work they did was very hard, hot and heavy. In consideration of this fact they were given an extra ear of corn or a camote at noon, in addition to the regular rations assigned to all work details. The detail lasted until 1 September, at which time the Japanese suddenly decided that enough work had been done there by the Americans, and allowed the finishing touches to be performed by Filipino labor.

The farm detail proved to be heavy during this year, and there are frequent reports of beatings and mistreatment of prisoners. The new camp commander who had come from Davao decided that a picked detail of American carpenters and mechanics should be selected to construct a house for him. The men, mostly officers, spent several months in the construction of this dwelling, but it was still unfinished when the Americans returned to liberate the Philippines.

Pay. -- No pay was given to either officers or men until November of 1942, at which time the Japanese announced that a pay schedule had now been drawn up, and that henceforth the American officers would receive the pay of the corresponding rank of the Japanese officers. They would, however, be charged for quarters and subsistence, and a large portion of the balance of their pay remaining would be put in their account in the Japanese Postal Savings. The announcement also stated that the enlisted men and non-coms would receive ten centavos each day that they worked.

The rise of prices for foodstuffs and commodities in Manila and nearby markets in 1943 operated to make the pay rate for officers and enlisted men less valuable than it had been before. Only after many requests from the American authorities did the Japanese finally grant a slight increase in the pay rate. But even this increase had little effect on purchasing power, for by that time prices of goods had gone completely beyond control.

There was little or no change in the pay schedule in 1944. But the prisoners began to experience difficulty in getting their pay. There were a few months when the Japanese "forgot" to pay them. Always before, when details left Camp Cabanatuan they were given their pay card to carry with them. This was not done in the case of those details that left after September 1944. Nor did the prisoners who remained in the camp receive any pay after that date.

Burials. -- Burial parties were composed of the healthier Americans, who reported to the hospital area each morning, accompanied by a Japanese armed guard. Four men were assigned to each body. After all the bodies to be buried that day had been placed on bamboo frames, the burial detail, regardless of weather conditions, would move to a distance of about one and one-half miles from the compound to an area designated by the Japanese as the burial grounds. Here the bodies were dumped into shallow graves, about four feet deep, and half-full of water. Usually fourteen or fifteen bodies were placed in a single grave. For the first few months the Japanese would not allow an American chaplain to accompany these details. Toward the end of 1942, however, they rescinded this order and granted permission for one chaplain to accompany each burial detail.

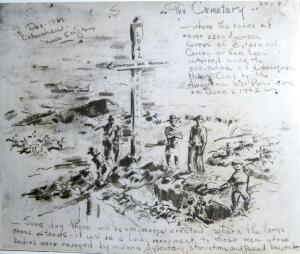

During 1943 the number of deaths fell to only a few persons each month. The situation, insofar as burials were concerned, was also greatly improved. A detail was assigned to improve the cemetery grounds worked with such vigor that by Memorial Day, 1943, a fence had been erected around the cemetery, the graves marked, and a large cross placed at the entrance. This year the Japanese permitted the Americans to hold Memorial Day services for the first time since their internment. They also furnished wreaths for the occasion, which were placed on a small concrete memorial monument. At this time there were some 2,500 Americans buried in the cemetery. Throughout the remainder of the year a chaplain was permitted to accompany each burial party and to conduct a brief burial service.

There were very few deaths during 1944. Those who were buried were placed in separate graves, each with a marker. The burial detail continued to function, and the cemetery took on a new aspect in consequence of their devoted labor. Wooden crosses were placed over all the graves, and the huge cross erected at the entrance of the cemetery was marked with the inscription, "American Prisoner of War Cemetery." Memorial Day exercises were again allowed at the cemetery, but because of the heavy work details only a few were able to attend and these men went only under a heavy guard.

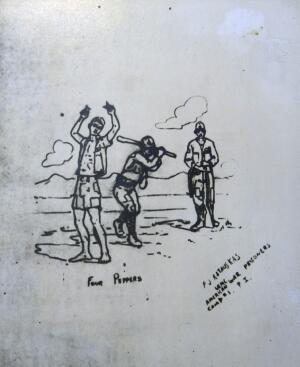

Brutalities and Atrocities. -- The thread of the story of Japanese brutality toward their American prisoners runs all through every account heard of life in the prison camp. This brutality manifested itself in an almost sadistic refusal to permit the prisoners to lead even a semblance of a decent existence, so far as food, clothing, living quarters, and indeed almost every other phase of everyday life. But it also showed itself in specific acts of physical cruelty, inflicted sometimes in punishment of minor infractions of rules, but almost more frequently apparently for the sheer pleasure of wreaking a spiteful and cruel vengeance on the Americans, whom they hated with the awful hatred of a people driven by perhaps unconscious feelings of inferiority, and who, having managed somehow to gain a momentary advantage over the object of their hatred, can find no treatment sufficiently degrading to show their feelings of hatred, superiority -- yes, and of fear.

The guards kicked and beat the prisoners on the slightest excuse -- or indeed, frequently on no excuse at all. Several of the prisoners who attempted to escape were executed. After a few such more or less abortive attempts the Japanese administration instituted the so-called "shooting squad" order, according to which all the men in the camp were divided into squads of ten men each. If any one of the ten succeeded in escaping, the other nine were to be summarily executed in reprisal. Actually, there is only one instance known at Cabanatuan of a "shooting squad" having been shot for the escape of one of its members. In spite of the rule, the usual punishment meted out to members of a "shooting squad" for the attempted escape of one of the group was solitary confinement and short rations. Nevertheless, the rule naturally operated to curb the number of attempted escapes, even though it did not entirely prevent some of the prisoners from continuing their efforts in that direction.

Several prisoners who attempted to barter with the Filipinos for food and medicine were also executed, after having first been tied to a fence post inside the camp area for two days.

A telegram sent by Secretary of State Cordell Hull, protesting the treatment of American nationals in the Philippine prison camps, cites evidence presented by escaped American prisoners of war as to the treatment accorded them in these camps:

At Cabanatuan during the summer of 1942, [the telegram stated] the following incidents occurred: A Japanese sentry beat a private so brutally with a shovel across the back and thigh that it was necessary to send him to the hospital. Another American was crippled for months after his ankle was struck by a stone thrown by a Japanese. One Japanese sentry used the shaft of a golf club to beat American prisoners, and two Americans, caught while obtaining food from Filipinos, were beaten unmercifully on the face and body. An officer was struck behind the ear with a riding crop by a Japanese interpreter.The discipline exercised over the prisoners by the Japanese reached almost inhuman levels during 1943. One supervisor and ten guards were assigned to every prisoners' work detail of one hundred men. The members of the camp farm detail suffered particularly from brutal treatment at the hands of their guards. Every supervisor carried a short club or golf stick, which they did not hesitate to use indiscriminately on the prisoners whenever the fancy struck them. In many instances a wholesale campaign of beatings and torture was visited on the farm detail for no cause whatsoever. Every day from seventy-five to one hundred men in this detail had to be treated on the spot, or were carried back to the camp unconscious from overwork or beatings.

Some of the most common methods of torture visited daily on practically every detail were slapping contests, in which the Americans were forced to slap each other for indeterminate periods of time: "endurance tests," in which they were forced to stand in the hot sun for a half-hour or longer holding a fifty-pound stone over their heads, or to kneel down for the same length of time with a 2 x 4 board under their knees. The only detail that seemed to escape these fiendish tortures was the wood-chopping detail. The reason for this exemption was probably that it was an outside detail that worked several miles from the camp, and also that its work was vitally necessary for the upkeep of the camp, and for the welfare and comfort of the Japanese as well as the Americans.

Several prisoners who tried to escape this year were executed, and a few times the Japanese imposed mass punishment on the prisoners for individual infractions of regulations. The mass punishment most frequently invoked were a decrease in the amount of rice issued, or a temporary suspension of commissary privileges.

As the course of the war turned against the Japanese Army, the camp authorities seemed to grow increasingly more brutal in their treatment of the Americans. In 1944 beatings were of almost constant occurrence, particularly in the farm detail. Every day new instances were reported of the Japanese guards administering severe beatings to the American prisoners working on the farm. There were also several executions during this period.

Recreation. -- What with the exhausting labor demanded of them by their captors, the necessity for taking care of their own personal needs such as repairing and laundering their clothes, keeping their barracks in some semblance of order and habitability, etc., the American prisoners, most of whom were in a constant state of fatigue and exhaustion anyway, as a result of too little food and an excess of anxiety and strain, had little time for recreation. Nor was there much opportunity to indulge in it. And, to tell the truth, many of them, in their weakened and despairing state, had little desire to amuse themselves. Fortunately, however, there were those among them whose knowledge of human psychology made them realize how important it was for the men to have something outside of the common routine of their daily existence to divert their minds from the unpleasantness and unhappiness of their existence. It was largely due to the efforts of these few wise ones that the prisoners at Cabanatuan made definite and concerted efforts to promote every form of recreation available to them, and to manufacture others, in an attempt to lift their morale, and to keep them from sinking into the lethargy of complete despair. How well they succeeded is witnessed by the variety of amusements which they managed to contrive in spite of their limited resources, and even more by the amazingly high morale of the majority of the men throughout the three years of their imprisonment. True, there were some who made no contribution toward this effort -- who, in fact, sank into a state of complete indifference, even to the point of torpor. But it must not be forgotten that the men at this camp were not a selected group. They were a true cross-section of American life. Among them were people of all degrees of wealth, education and culture, from the highest to the lowest. Every occupation and profession were represented here, every type of personality, every shade of opinion, political, social and religious. Can it be wondered at, then, that the personal reactions to the situation in which they now found themselves were so various, or that there was not always a unanimous response to the efforts of the more active among them to increase and enlarge their opportunities for recreation, and to keep alive in them, buried as they were here, far away from the lives to which they were accustomed, at least a little of their normal response to leisure-time activities, and a little of their taste for amusement and entertainment? In spite of this variation, however, most of the men did co-operate well with the efforts of those in charge to help them fill their leisure hours with congenial as well as instructive tasks.

A few of the first prisoners to come to Cabanatuan had been fortunate enough to be able to bring with them some reading matter, mostly a few works of fiction, some technical books, and a few scattered magazines. The authorities set aside one small building in the prisoners' area to be used as an exchange center for these books and periodicals. Here a man who had a novel could bring it in and exchange it for a magazine, or a serious technical treatise, or a magazine belonging to some one else in the camp. When he had read it, he took it back to the center and exchanged it for another book belonging to some one else. In this way, all the available reading matter in the camp, scant though it was, was circulated among all the prisoners. The scheme worked out so successfully that the building was made into a library the following year. True, the choice was limited. But the books that were there were read and reread, until pages became worn and soiled and dog-eared from constant handling. Indeed, many of them saw such strenuous use that they fell apart and could be read no longer.

Some of the men had brought decks of playing cards with them, with which they whiled away many a heavy hour. Several ingenious devotees of cribbage contrived boards on which to play their favorite game. There was almost no athletic equipment in the camp, but on a few rare occasions the Japanese provided baseball equipment and permitted the prisoners to indulge in a baseball game.

Some of the chaplains, particularly in the hospital area, organized study groups. The men in these groups studied an astonishing variety of subjects, under the direction of any one in the camp who had special knowledge of that subject. Technical information seemed to be most in demand, and the classes in those subjects were taught by technical specialists among the officers' group. Brief lectures were also given from time to time by those of the prisoners who had specialized technical and professional knowledge. These lectures, however, had to be given without the knowledge of the Japanese guards, and popular as both they and the study groups turned out to be, they could not be continued for long, because the Japanese frowned upon group gatherings of any kind, apparently fearing, probably rightly enough, that such gatherings would afford too much opportunity for the men to engage in "subversive" conversation, or even to plot rebellion or escape.

Those among the prisoners who could play a musical instrument were soon organized into a small orchestra, which furnished entertainment from time to time. And during the Christmas holidays a choral group entertained the patients in the hospital areas with Christmas carols.

In the early part of 1943 the Filipino charity organizations in Manila, with the permission of the Japanese, sent the prisoners a small organ, which was used for religious services, as well as for the programs put on by the entertainment unit. Throughout the rest of this year this unit produced amateur shows once a week. They also exhibited some old American films and a few Japanese propaganda pictures to the prisoners.

The supplies from the American Red Cross in December 1942 included some games, and a number of new books, all of which were gladly welcomed by the internees. The books found their way, along with those already on hand, into the library that was established this year from the nucleus of the book exchange center set up the previous year.

Reading classes were held this year for those whose eyesight had deteriorated as a result of malnutrition.

The games that had come into the camp from the Red Cross were of inestimable value in keeping up the morale of the prisoners. But the men also devised many other ingenious methods of maintaining their spirits. And, in spite of the fact that they had little leisure time, they accomplished a great deal in this direction. They launched contests aimed at beautifying the grounds around the barracks. Other contests were held every month in wood-carving, metal work and other handicrafts, and an amazing amount of interesting and really superior work was turned out by the participants. All in all, they found a surprising number of ways to occupy their leisure time, scant though it was.

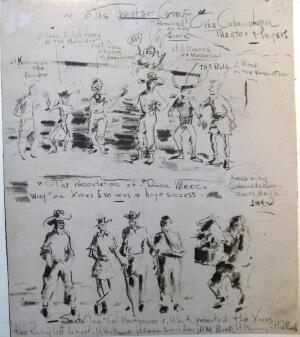

The Cabanatuan Theater Players

[Names listed: Lt. Manning, Lt. Swan, Capt. Don Chillers,

T. Brownell, Lt. B. Mossell, Lt. Burell, Col. Montgomery]

The entertainment unit continued to function throughout 1944, although some of the projects it had initiated, notably the camp band, suffered considerably from the loss of personnel by death, as well as by shipment to Japan. It did, however, accomplish its purpose of keeping the prisoners' morale at a reasonably high level during these difficult days.

Very few Japanese movies were shown in 1944, mainly because they could no longer be obtained from the Filipinos who controlled the film in Manila. More books came to the camp this year, and the men devoted an increasing amount of their leisure time to reading. After a few months, however, the Japanese withdrew these books from the library, to be censored, so they said, re-issuing them to the prisoners in small lots some time later.

The men continued their handicraft work, and several contests in craftsmanship were held. It was interesting to observe the ingenuity they displayed in fashioning the most surprising objects out of scrap, the only material at their disposal for this purpose. One officer contrived a loom from tin cans and Red Cross packages. Some one else made a violin from a tabletop, with only a GI knife to do the carving. Still others made pipes, wood carbines and plaques. More decks of playing cards had come with the last shipment from the Red Cross, and card playing became almost the principal form of recreation.

Religious Services. -- In the early days of the main camp at Cabanatuan the Japanese refused to permit the American chaplains to hold either burial or religious services for the men. Toward the latter part of 1942, however, they withdrew their refusal, and thereafter the chaplains could conduct services at stated times during the week, provided they submitted their sermons to the Japanese for censorship before they were delivered.

In 1943 two buildings at either end of the prisoners' compound were designated as chapels for religious services. Here the Catholic chaplains held mass every morning, and the Protestants conducted Sunday services. Services were also held in the Hebrew faith. An organ sent to the camp by some charitable organizations in Manila was placed in the chapel. It added much to the men's enjoyment of the religious ceremonies. Different religious societies in Manila also sent religious books and articles to the prisoners. Certain chaplains were assigned to duty in the hospital area, where they were permitted to conduct services and minister to the sick and dying.

The greater freedom accorded to the chaplains in 1943 continued throughout the following year, and in spite of the critical shortage of religious supplies they were able to conduct services comparatively unmolested. A chaplain was even permitted to conduct Memorial Day services at the camp cemetery. Through the efforts of individual chaplains the chapel grounds were improved and beautified. A marked interest in religion on the part of the prisoners is noted in the records kept by the chaplains at the camp.

Col. Alfred C. Oliver Jr., an American army chaplain who was captured at Bataan and imprisoned at Camp O'Donnell, and later at Cabanatuan -- he was in the latter camp from 2 June 1942 until 30 January 1945, when he was rescued by the American Rangers -- has written a graphic account, effective and moving beyond words, by its very simplicity, of the work the chaplains did and the suffering they endured in their efforts to bring the comfort and solace of spiritual aid to the men at this latter camp. In a report entitled, "The Japanese and Our Chaplains" he says:

The policy of the Commanding Officer... was far stricter than that at Camp O'Donnell especially in the first three months. During this period he would not permit the Chaplains to hold any religious church services; he would not permit them to even bury the dead...Perhaps no better words can be found with which to convey the importance of the contribution of our army chaplains to the religious life of these suffering men at Camp Cabanatuan than those of the moving little story with which Chaplain Oliver concludes his report:

...The Chaplains daily went from man to man giving what spiritual help they could. When death occurred these poor emaciated bodies were stacked in a small morgue, where each morning, at the risk of their lives, the Chaplains held appropriate religious services. The Chaplains were not permitted to go out with the bodies to hold burial services, but had to stand sadly by and watch a detail of American prisoners load these naked skeletons on bamboo litters.

-------------------------------------------------

Along in the fall of 1942 there was a change in Japanese policy. Chaplains were permitted to bury the dead, but in order to hold a religious service the Chaplain was required to present to the Japanese a copy of the sermon to be delivered not later than Thursday of each week. Often the Japanese censor would cut out great portions of the sermon and there would be no time to rewrite. What was approved had to be delivered exactly as written. At that time all services were held out in the open from a stage erected for camp entertainment; by spring the Chaplains were permitted to use two-thirds of the camp library building for religious services. A schedule was established so that denominational services did not conflict. In spite of an apparently more relaxed attitude of watchfulness the Japanese censorship persisted. Time after time an interpreter would walk down to the front of the building where services were being held and sit there with a copy of the approved script in his hand. Only a minister can realize how hard it is to deliver a sermon under such conditions. The hymns to be used also had to be approved. On a Sunday nearest to July 4, 1943 the Protestant Chaplains took a chance and had the congregation sing "God Bless America." The next morning the Japanese camp commander called the American camp commander to account for this breach in orders, warning him that a repetition of this incident would bring severe punishment on the Chaplains. The song had been used as the closing hymn of the service. How the Japs learned about it will ever remain a mystery.

Early in 1943 an accurate religious census of the entire camp was made. This showed that 26% of the men were Roman Catholics and the remaining 74% divided among the Hebrew and Protestant faiths. By this time the Catholic Chaplains were holding an average of six masses each morning and three Rosary services each evening. The Protestant Chaplains were holding eight regular preaching services on Sundays and four prayer meetings on weekdays. At the meeting of the Protestant Chaplains it [was] determined to organize a Protestant church representing all the denominations in camp. This church was patterned after the one instituted at Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C., and grew rapidly until it had a membership of around 1500. It was the first church of this scope and character in the history of the world. Hundreds of men who never before had taken a stand for Christ acknowledged him and were baptized by a Chaplain of their own faith, then publicly received into the Church membership... The good this unique organization accomplished is beyond human estimate.

The Japanese would not permit the Chaplains to leave camp either on local details or under permanent transfer until the middle of 1944. Constantly groups of men, as high as eight hundred at a time, were sent out to work on local air fields and before June 1944 thousands were sent to Japan or Manchuria. Every time a group left, the Chaplains appealed to the Japanese mission to go along and care for the spiritual needs of these men. In each instance the appeal was denied. The Protestant camp church met the challenge by training laymen for spiritual leadership through Bible study. One man in each out-going group was appointed spiritual leader. He was furnished with as many copies of the New Testament as could be spared, a supply having been sent from Manila by the American Bible Society. These were insufficient and had to be used sparingly. Each leader was also furnished copies of the baptismal and burial services. It was learned later from sick and injured men who returned from these details that these services held by laymen were a source of great consolation and strength.

On Memorial Day, May 30th, 1943, the Japs permitted camp services at the cemetery. Every man in camp wanted to attend this special ceremony but only fifteen hundred were allowed to go. All but a small group of Chaplains were lined up outside the cemetery fence. A chorus sang "Rock of Ages," and "Sleep, Comrades, Sleep." Prayers were read by Protestant Catholic Chaplains and a Jewish Cantor gave part of the Jewish burial ritual. One could hardly recognize this plot as the cemetery of 1942. At that time the mud was shoetop deep, bloody water stood in the ditches and the air was full of the stench of rotting bodies. Now, the ant hills which had infested the cemetery had been destroyed. Graves had been built up and leveled off; paths had been made; the entire area had been ditched, the stream controlled, and white crosses with the names of the two thousand six hundred forty-four who had died there, erected. Those attending the service returned to camp with thankful hearts that in these small ways loved ones had been cared for...

On the now famous twenty-five mile hike to liberty [he says] the little band of American prisoners straggled quietly along through Japanese-held territory in East Central Luzon. One weary soldier drew near a Chaplain for companionship, walking in silence for a while. Barefoot, without shirt or hat, his entire covering consisted of a pair of patched pants. Finally, out of thoughts evidently far away, he spoke slowly, not looking at those near him. With head uplifted and eyes on the fading stars of the western sky he said, "You know, Chaplain, I lost everything back there in that hellhole of a prison camp, every earthly thing including my health -- but I didn't lose God." He said no more, and together he, the ragged soldier, and the worn chaplain moved forward toward freedom and Christian liberty.[Short video clip: US Army chaplain Colonel Alfred Oliver is interviewed after being liberated from a Japanese prison camp in the Philippines]

|

"Dec - 1942, Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija. "The Cemetery ~~ where the bodies of over 2500 American heroes of Bataan and Corregidor have been interred since the occupation of Cabanatuan Prison Camp by the American War Prisoners on June 2, 1942 ~~" [Inscription on cross: "INRI 1942 CABANATUAN - AMERICAN WAR PRISONERS"] "~~ Someday there will be a memorial erected where the large cross stands -- it will be a living monument to those men whose bodies were ravaged by malaria, dysentery, starvation and passed beyond ~~" [These prophetic words have been fulfilled -- see Cabanatuan American Memorial and also here.] |

Correspondence. -- All through the months of 1942 the prisoners were not permitted either to send or receive any mail. The Japanese authorities made no attempt to notify the United States War Department of the names of those who had been taken prisoner until well into the following year, and even then the list was only a partial one. As a consequence these men were all officially reported as missing in action, and until the next year, when they were allowed to send brief messages home, their families remained completely in the dark as to whether they had been killed, or were lying wounded in hospitals, or were incarcerated in Japanese prison camps.

The ban against prisoners receiving mail or packages still persisted through 1943, but this year each man was allowed to send a message of twenty-five words to his family every two months. The restrictions laid down by the Japanese as to what they might mention on these cards, as well as the necessity for confining their messages to twenty-five words, naturally made it impossible for them to send very satisfactory news of themselves. But it was a comfort to the men to be able to send even that limited amount of direct news, and just as heartening to their families to receive it. As a matter of fact, however, many of these messages never reached those at home. Some of it was probably lost in the mazes of censorship, while some went down with the Japanese ships that were sunk by the Americans, and a great deal was no doubt simply never sent by the Japanese.

In January 1944 the prisoners at Cabanatuan received a telegram from the American Red Cross wishing them a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year, and in March of that same year a number of packages of mail arrived for them. Although this mail had already been censored at two or three other places, the Japanese camp authorities decided that they should censor it again. Since they had only one officer to do the censoring, the task necessarily proceeded at a very slow pace, with the result that the mail trickled out to the prisoners at first at the rate of only fifty to seventy-five letters a day. By September 1944, from three to four hundred letters were being issued every day, and by October all of the letters that had been received up to that time had been censored and delivered to the prisoners. Unfortunately, several shiploads of prisoners had been sent from the camp to Japan during the intervening months, and many of the men therefore did not receive their mail.

In March 1944 the prisoners received packages from home. In most instances only one package was delivered to each prisoner. These packages had been allowed to lie around in the warehouse in Manila so long that only about 10 per cent of them were in good condition, or their contents fit for use, when they were delivered.

Restrictions were lightened this year to permit the prisoners to send out one card every month, instead of every two months, as in the previous year. Limitations as to the number of words and the type of message that could be sent still persisted, however.

Movements of Prisoners. -- Throughout the entire existence of Cabanatuan camp its population was constantly changing. New men came in to swell the number of those already there, while death stalked the area, ruthlessly cutting down their ranks. And even more important as a factor in the ever-changing face of the camp were the evacuations to other camps, both in the islands themselves and in Japan.

Several shipments of prisoners were removed from Cabanatuan in 1942, one detail of approximately 400 technicians having been sent out almost immediately after their arrival in June 1942, presumably to Japan. In October 1942 about 1,000 men were sent to Japan, and the same number to Davao Prison Camp, in the southern part of the islands, where they formed the nucleus of the Davao Prison Camp. (This camp will be discussed later in this report.) Smaller details were also sent to Bataan, and to the airfields in and around Manila.

Several more large shipments of prisoners left the camp in 1943. Their destination was unknown, but from later reports it is believed that the larger details, after having been cleared through Bilibid Prison, were sent to the Japanese home islands, while the men in the smaller details were used on local projects, such as bridge building, road repairing, and salvage work. It is known that these smaller details were later sent to Bilibid, and from thence to Japan. As a result of these mass movements of prisoners from Cabanatuan, the population of the camp dropped by the end of 1943 to approximately 4,000.

Early in 1944 several large groups of prisoners, mostly skilled mechanics, technicians, and common laborers, were shipped out of the camp, where is not known, although it is presumed that they, too, went to Japan. The men were selected by lot by the American administration, and examined by both American and Japanese doctors. In the event that any man was rejected by either of the two examining physicians he was replaced by a prisoner from a group of alternates also chosen by the American administrative staff. Part of each detail -- about 10 per cent, in fact -- was also made up of prisoners who volunteered for the job.

By September 1944 the population of the camp had been reduced to approximately 3,200, including the hospital patients. Then the first American planes appeared over Luzon, whereupon the Japanese camp authorities began to make hurried preparations to evacuate the camp. That same month a detail of almost 1,000 prisoners was sent to Manila, and from there to Japan. (Further details about this group will be related in the report on the Bilibid Prison Camp.) In October the entire camp was evacuated, except for 511 permanently disabled men, who remained at Cabanatuan until they were liberated by the United States Rangers in January 1945. The 1,700 men removed from the camp were taken by truck to Bilibid Prison Camp, and later sent to Japan.

The prisoner of war camp known as Old Bilibid Prison Camp was located in the heart of Manila, not far distant from Santo Tomas University, where the Allied civilians were interned during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. Designed and built under the auspices of the United States Government during the American occupation of the Islands as a place of detention for Filipino criminals, Old Bilibid had, before World War II, been regarded as an extremely modern penal institution.

It comprised approximately eleven long, low, one-story buildings, one large main building formerly used as a hospital, and, at one end of the prisoner grounds, a two-story administration building constructed partly of wood and partly of concrete. Under the old administration, prior to the Japanese occupation, one of the small buildings had been set aside as an execution chamber.

The prison grounds were laid out in the form of a wheel, of which the high stone wall surrounding the grounds formed the rim, and the long, low buildings the spokes. The wall had entrances at three sides, and was topped by a walk on which guard towers were erected at certain intervals, manned by guards who were thus enabled to patrol the camp at strategic points. From this description it may readily be seen that this prison was extremely well equipped, in the best modern manner, to insure that its occupants had scant opportunity to escape alive from within its walls.

When the Japanese entered Manila they took over Bilibid Prison, with the intention of using it as one of the prisoner of war camps they were establishing in the Philippines; and, indeed, they did use it as an internment camp for those prisoners they took in the early days of the campaign, before the fall of Bataan and Corregidor. Upon the surrender of the Americans, however, and after the Japanese had actually occupied all of the Philippines, this prison was used by them as a clearing house and transfer point for all prisoners of war who were being sent to other prison camps in the Philippines, or to Japan.

As in the case of Cabanatuan camp, this prisoner of war camp will be discussed here with respect to its administration, sanitation, food, etc., during the years 1942-45, when it was in operation. Since the Japanese failed or refused to notify either the Swiss Government or the International Red Cross of all the movements of the prisoners of war in and out of Bilibid during that time, however, our statistics as to those movements have had to be compiled, for the most part, from the affidavits of escapees, liberated prisoners of war, and from Military Intelligence reports, and are, in consequence, very meager, and, in some instances at least, incomplete.

In the latter part of May 1942 all of the American prisoners of war captured on Corregidor were marched through the streets of Manila to Bilibid Prison. Here they were met by another group of prisoners who had been captured before the fall of Bataan and Corregidor, and who were now assigned to this camp as a permanent detail, to aid in its administration, and to clear the transient prisoners of war through it to other camps.

When the prisoners of war from Corregidor arrived at Old Bilibid their captors searched them, and stripped them of all articles such as knives, forks, watches, flashlights, extra clothing and any other personal possessions which the Japanese deemed it unnecessary for prisoners of war to have. Each man was allowed to keep only one uniform, a shelter half, and a blanket, as well as any mess gear he might have in his possession, including a spoon. Many of the prisoners were unable to obtain a mess kit or water canteen, and had to utilize any kind of container they could find, such as cans, pieces of sheet metal, or even cocoanut shells, if they were to eat and drink.

They stayed at Bilibid only a few days, at the end of which time they were sent in groups, on successive days, to the prison camp at Cabanatuan. Several hundred volunteers were retained by the Japanese authorities to be used as permanent work details in and around the city of Manila. These men were housed and quartered at Bilibid Prison, and, together with the first prisoners already referred to, who were aiding in the Administration, constituted the initial cadre of Bilibid Prison Camp in Manila.

The sick and wounded from Corregidor were not transferred to Cabanatuan along with the other prisoners, but were kept in a section of Old Bilibid Prison reserved for patients. They were joined later that summer by another large group of patients from Corregidor Hospital. There was also a large influx of patients from Camp O'Donnell, mostly men who had originally been confined in U.S. Army Hospital No. 1 on Bataan, and who had been taken when that stronghold fell.

Administration. -- For the first few months after the contingents of American prisoners of war from Corregidor arrived at Bilibid, the Japanese were so much occupied with administering civilian affairs in Manila itself that they had little time to spare for establishing any definite administrative policies in the prison camp. The Japanese officers in charge of the camp seemed apparently quite content to restrict their efforts to seeing to it that the few hundred prisoners permanently assigned there were kept busy on the various clean-up and salvage details used throughout the city. They kept almost no records, and left all routine matters concerning the new prisoners, such as roll calls, discipline and organization of work details largely in the hands of the American administrative staff.

The hospital staff was made up of physicians and medical corpsmen comprising the medical staff of the former Naval Hospital at Canacao, as well as a few civilian doctors. Most of the routine administrative tasks connected with the management of the work details were performed by naval medical officers on this staff.

In August 1942 an administrative force arrived from Japan to take charge of all the concentration camps, for prisoners of war and civilians alike, established in the Philippines by the Japanese. Immediately upon taking office the new commandant, Lieutenant Nogi, announced that he intended to run the prison on accordance with the rules laid down by the Geneva Convention, except that every American, whether officer or enlisted man, would be expected to salute or bow to all Japanese soldiers, regardless of their rank. He told the prisoners that a set of rules was to be posted in each building for the guidance of all prisoner of war patients and duty personnel in Bilibid. These rules, he warned, must be strictly adhered to. He also promised that conditions in the camp would soon improve.

The lieutenant was as good as his word. The promised regulations were posted, and a more rigid guard system was established to patrol the compound. Within a very short time conditions, particularly in respect to food, sanitation and recreation, were much better. A commissary officer was appointed to act as purchasing agent for the camp. It was his responsibility to contract with the Japanese and Filipino merchants for food items to be purchased by the prisoners of war. A staff was also chosen to cook and issue food to the patients and working personnel. This galley crew worked in the kitchen under the supervision of an American officer. A sanitation detail was designated to police the compound and make necessary improvements in latrines and urinals. One Japanese and one American interpreter were detailed to the Japanese headquarters as liaison officers, and a number of the American prisoners were also detailed there as clerks and typists.

The increased efficiency of both the Japanese and American administrative forces at Bilibid was reflected in the marked improvement that soon took place in living conditions there, an improvement that continued through 1943. The Japanese authorities made some attempt to keep careful records of the prisoners stationed at the camp, as well as of those who came and went constantly on work details. All in all, a great deal was accomplished this year for the welfare of the prisoners. The food became much better, with the result that there were fewer prisoners ill, and thus more of the better grade men became available for administrative work.

The following year the Japanese sent some of the American army officers who had been on the administrative staff to Cabanatuan, installing a group of Navy officers in their place. This new staff functioned very efficiently until October 1944, when they, too, found themselves relieved of their functions and placed on the list of details to be sent to Japan. Now an entirely new American administrative staff, made up mostly of doctors and medical corpsmen, was put in charge, and remained in control until the camp was liberated by the invading American forces on 4 February 1945. During the period of their administration this last staff conducted extensive surveys of the condition of the patients in the camp, and also increased the number of routine inspections.

Housing. -- The buildings in which the prisoners were housed at Bilibid were long, low concrete structures, approximately 200 feet long and 50 feet wide. They did have a sufficient number of windows to supply ample light and air, even though they were barred. But they were poorly insulated, and the concrete floors and walls remained damp for long periods of time after every rainfall, thus providing excellent breeding places for bedbugs, cockroaches and mosquitoes, with which the buildings were infested.

In some buildings the roof had been damaged by bombs, and had been repaired with makeshift materials, such as strips of corrugated tin, or even cardboard. During the period from January to May 1942, Japanese soldiers had stripped the buildings of all furniture, as well as of part of the plumbing and lighting fixtures. When the American prisoners first came from Corregidor they were forced to sleep on the damp concrete floors. This situation was remedied, however, when the new Japanese administrative staff took over in August 1942.

The year 1943 saw considerable improvement in the housing situation, what with repairs, additions and changes that were made. Some additional beds and bedding were brought in, showers were repaired, and water facilities throughout the buildings were improved.

The next year, however, very few improvements were made in either barracks or quarters. The wooden shutters on the windows began to show signs of wear from all the typhoons and other adverse weather conditions of the two preceding years, and, though the roofs of some of the buildings were in fair condition, some of them showed gaping holes. The Japanese made no attempt to assist the Americans in their attempts to repair either the roofs or the windows. They did, though, keep the electricians among the prisoners constantly on duty to repair and maintain the electric facilities of the camp.

After October 1944 many patients were shifted from ward to ward, apparently because of the desire of the Japanese to concentrate them in a smaller area, for administrative reasons.

Sanitation. -- When the naval officers from Canacao Naval Hospital took over the administration of the work details at Bilibid around June 1942, they found several hundred prisoners of war lying on the bare floors of the barracks covered with flies. Some were dying, some suffering from uncared-for wounds, and many were ill from malnutrition or different tropical diseases. Corpsmen were immediately assigned to the task of cleaning up the patients, washing the floors of the buildings, and generally improving sanitary conditions throughout the compound.

The Japanese entered no objections to any improvements the Americans wanted to make, but they refused to cooperate to the extent of providing the necessary materials. The men who went out into the city on work details every day, realizing the need for these materials, every evening would bring back to the compound any tin, wood, nails, and other materials for construction that they could lay their hands on during the day. With the materials thus obtained the sanitary detail installed several urinals and sanitary latrines, and devised a flush system for the latrines, consisting of a large gasoline drum suspended on a pivot at the end of each latrine. Under this drum was placed a spigot connected to a water pipe running into the drum. When the water from the spigot reached a certain height in the drum, the drum would tip to one side and the water in it would spill down into the latrine, thus flushing the contents into a main drainage system that led outside the camp.

The sanitary detail also put in a series of wash basins along the inside of the wall that surrounded the compound, and set up trench disposal units, consisting of enclosed ovens with wood fires underneath them, in remote spots throughout the camp.

During 1943 a few slight additional improvements were made in the sanitation of the camp. The Japanese issued some insecticides, which were very well received, and, as the health of the patients improved under the slightly better food and the indubitably better living conditions, individuals and groups alike took more pains to give better care to their clothing, as well as to the barracks and to hygienic conditions in general.

Sanitary conditions in the camp remained virtually unchanged the next year, except that after September, the increased number of transient details arriving at Bilibid from Cabanatuan en route to Japan put something of a strain on the prison water supply. This was only temporary, however, and soon readjusted itself after each contingent had departed.

Food. -- Food was a serious problem for the prisoners of war at Bilibid during the early days of their internment. Throughout the first year the normal amount of food issued by the Japanese consisted of about 90 per cent of rice of the very poorest quality, and a small quantity of greens, which were used to make soup. On rare occasions the Japanese also issued small quantities of meat or fish. The average daily menu for the prisoners consisted of one cup of boiled rice for breakfast, another cup of rice and a bowl of soup made of vegetable greens for lunch, and the same for dinner. A slight improvement was seen after the new Japanese administrative staff took charge in August 1942, for they authorized the establishment of a commissary under the supervision of an American officer, who made contracts with Japanese and Filipino merchants to supply certain items of food to the prisoners. This commissary proved to be a great benefit to all the prisoners, either directly or indirectly. Those who had money were able to buy such items as mongo beans, bananas, and garlic to supplement the monotonous rice diets furnished by the Japanese. They could even purchase small amounts of tobacco from time to time.

In November 1942 the Japanese began paying the American officers, non-commissioned officers and medical corps. The purchasing power of the camp now rose to great heights. Soon the demand far exceeded the supply, and prices began to soar. A fund was established from contributions made by the paid personnel, to purchase additional food for the seriously ill patients who had no funds of their own and were not receiving pay. The additional food obtained thus from the commissary was instrumental in saving the lives of many men who would otherwise have perished. But even so, the food situation at Bilibid was never adequate, and many did die of malnutrition and starvation. Of the approximately one thousand patients who were hospitalized at Bilibid during 1942, one-fourth died during the first six months of their internment, many of them from malnutrition or starvation, or diseases directly attributable to malnutrition.

The arrival of Red Cross packages at the camp in December 1942 caused considerable improvement of the food situation for the first few months thereafter. Early in 1943 the Japanese also began to issue small quantities of meat and fish regularly, in addition to the customary daily issue of rice. This increase in food rations, while it did not serve to reduce the number of patients already suffering from malnutrition, did help prevent any increase in the incidence of vitamin deficiency diseases. The additional supplies obtained from the commissary were also of great help during the first few months of 1943 in keeping down the number of deaths and in preventing the outbreak of epidemics resulting from malnutrition.

In the latter part of the year, the food situation again became critical. During these months the diet consisted almost entirely of rice and soup made from greens, varied only occasionally by a tablespoonful of dried fish. In September the Japanese ordered that individual purchases through the commissary be limited to seven pesos per month. But they also allowed any person who wished to do so to contribute a few pesos to a general mass fund. With these new regulations, and with the prices of commodities soaring, it became almost impossible for the commissary officer to have sufficient funds on hand to purchase any great quantities of food for the camp. Indeed, almost the only articles that could be obtained through the commissary at this time were mongo beans, garlic and tobacco. Soon the commissary was, for all practical purposes, practically non-existent. Once again the arrival of Red Cross supplies, this time about three boxes for each man, proved to be the salvation of the starving prisoners.

For the first few months of 1944 the Japanese steadily cut down the amount of food issued to the prisoners of war. The Red Cross packages that had arrived late in 1943 supplemented the rice diet as long as they lasted, but from February on the Japanese themselves issued nothing but rice to the prisoners, except on very rare occasions when they gave them a little meat or dried fish.

A diet kitchen separate from the general mess where food was prepared was set up under the supervision of an American doctor for those who were seriously ill. However, the amounts of canned milk, vegetables and fruits issued to this kitchen were so small that the patients never received large enough quantities of this supplementary food to show any visible beneficial effects from it.

By August 1944 the food situation was well-nigh disastrous. From that time on for the next four months the daily issue of food for each person amounted to only 200 grams: 100 grams of dry rice, 50 grams of soy beans -- of the variety that it is impossible to cook and make palatable -- and 50 grams of dried corn. Because of shrinkage and theft, however, as well as for other reasons, the actual issue was not 200 but 170 grams. At 8 A.M. each prisoner received one canteen cup of rice boiled in so much water that it was actually a thin rice gruel. His second meal, at 8 P.M., was the same boiled rice, only this time cooked to a very thick consistency. Occasionally a few greens were boiled and made into a greenish-colored soup for the men. The only exception to this horrible diet was made on Christmas Day of 1944, when the Japanese issued some extra vegetables, a little sugar, and a few soy beans.

Under this starvation diet the prisoners grew emaciated and ill. Soon their average weight dropped to less than 120 pounds. The death rate began to rise rapidly. (The average number of men buried each day varied from one to four.)

When the American invasion forces arrived on 4 February 1945 the prisoners of war had reached such a point of starvation that none of them could have survived much longer. Many of them had fallen victim to tuberculosis, dysentery, beriberi and other tropical diseases, and practically all of them were suffering from malnutrition or acute starvation. What the coming of their rescuers meant to the prisoners at this camp can scarcely be imagined by one who has never himself been in a similar situation.

|

"On

the 29th of Dec., 1942 the second shipment of Red Cross Packages

arrived in camp -- The individual Package -- The Canadian Red Cross. "The Articles were: Soap, cheese, Luncheon Meat, Crackers, Chocolate, Prunes, Marmalade, Raisins, Tea, Sugar, Powdered Milk, Sardines, 1lb Butter, Salt and Salmon. "Some American Red Cross Packages at last arrived and contained the following: Evaporated Milk, Biscuit, Cheese, Cocoa, Sardines, Oleomargarine, Corn Beef, Chocolate, Sugar, Orange Concentrate, Dehydrated Soup, Prunes, Coffee, "Roy"? Cigarettes and "George Washington" Smoking Tobacco. "The Packages were presented to the Prisoners on New Years Day -- Due to the fact that all American packages were not yet rec'd half the men were given Canadian Packages and the other ???? were given American boxes." |

Clothing. -- When the American prisoners of war came to Bilibid in 1942 they had with them only the clothes they were wearing when they were captured. As time wore on these clothes became torn and ragged, and since no replacements were available except a few blue dungarees from the American quartermaster depots, the men had to patch their old garments as best they could with any kind of material they could lay their hands on.

During the first year of their internment their captors issued to them some 1,500 pairs of cotton socks of Japanese manufacture, and a few "G-strings" made of strips of very thin cotton cloth about 12 inches wide and 30 inches long, which the prisoners wore tied about the waist and pulled up between the legs. No shoes were issued to them, and since most of their own shoes were soon worn out they had to rely on home-made wooden shoes ("clacks").

Toward the end of the year the clothing shortage was alleviated somewhat by the distribution of a few items that had come in with the Red Cross supplies in December -- some felt hats, woolen garments, and a few pairs of socks. But still there were no shoes.

In January 1943 Commander Sartin reported that a survey revealed that there were one hundred men in the camp who were without any shoes at all, and that there were 275 pairs of shoes that were too worn out even to be repaired. Five hundred of the men, the report went on to say, were in need of trousers, and 200 had no undergarments at all. The Japanese installed a cobbler's shop and a tailor shop in the compound, under the direction of pharmacist’s mates. But this apparently helpful move did little good at first, for they neglected to supply the materials with which repairs could be made. By March, 150 of the men were without shoes, and those shoes that had not completely worn out were in too sad a state to be repaired. Then at last the Japanese did issue some leather, nails, thread, and other materials with which the men could repair their clothing and shoes. In April 1943, 101 pairs of shoes were distributed, and a few more the following month. Thereafter, however, the only shoes that were issued were old ones turned in by the prisoners themselves, which were repaired at the cobbler's shop and reissued at the rate of fifty a month -- just a drop in the bucket, in light of the great need.

No new clothing was issued to the prisoners during 1944. Late in the year two details, each comprising more than 1,500 men, who had come to Bilibid from Cabanatuan in August and October, respectively, were sent to Japan. Before they embarked they were given woolen Japanese uniforms, and their castoff clothing was distributed among the prisoners who remained at Bilibid. Aside from this unexpected and not altogether satisfactory addition to their clothing stores, the men at Bilibid continued to go around in their old patched and motley rags -- that is, those who had rags did so; for by this time even the rags were beginning to wear out. And when the American invasion forces arrived there in February 1945, they found many of the men stark naked.

Medical supplies. -- The Japanese furnished the hospital at first with approximately three or four hundred wooden bunks with straw mattresses, and toward the end of the year they also supplied an equal number of mosquito nets and a few blankets. The mattresses proved to be quite a problem, for with the constant use to which they were subjected they became more and more soiled; and since there was no way of cleaning them they were soon filthy and crawling with vermin.

Absolutely no medicines at all were issued by the Japanese for the care of the sick and wounded prisoners during the first few months of 1942. The only medicines available then were those that the prisoners themselves had brought with them and had been able to hold on to after they were captured. And these were, unfortunately, very few. In June 1942 the hospital did receive several thousand quinine tablets for the malaria patients, and thereafter the Japanese issued a sufficient quantity of quinine to enable the hospital staff to treat the current cases of malaria. But there was never enough for prophylactic treatment. The only other medicines available were a little bismuth and nine bags of powdered charcoal -- both utterly useless in dysentery. Later a little emetine, carbazone and yatren were issued at regular intervals, but never in sufficient quantities to permit the men to receive the full therapeutic dosage. When the United States Army unit from Corregidor arrived in July they brought with them some surgical supplies and a small amount of vitamin synthetic, all of which were thankfully received by the hospital staff.