|

Medical Report Philippines & Japan, 1941~1942 by Col. Wibb Cooper, Medical Corps "Never in the history of war has medical personnel been called upon to perform their duties under such arduous circumstances and over such a protracted period." |

| Main | Camp Lists | About Us |

MEDICAL DEPARTMENT ACTIVITIES IN THEPHILIPPINES FROM 1941 TO 6 MAY 1942,AND INCLUDING MEDICAL ACTIVITIES INJAPANESE PRISONER OF WAR CAMPS.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medical Department Officers | 247 | |||||

| Medical Department Enlisted Men | 717 | |||||

| Medical Department Philippine Scouts | 572 | |||||

| TOTAL: | 1536 |

The following Medical Department facilities were functioning:

(1) Department Surgeon's Office, ManilaFortunately, for several months prior to the War, most of the Regular Army medical officers at Sternberg General Hospital and the Station Hospitals had been replaced by Reserve Officers and the Regular Officers made available for assignment to and training with Regular Army and Philippine Army tactical organizations for use in connection with the training program in which the 12th Medical Battalion (PS) at Fort McKinley figured so prominently.

(2) Sternberg General Hospital, Manila

(3) Station Hospital, Fort William McKinley

(4) Station Hospital, Fort Stotsenburg

(5) Station Hospital, Fort Mills, Corregidor

(6) Station Hospital, Fort John Hay, Baguio

(7) Station Hospital, Petit Barracks, Zamboango

The bombing of Clark Field on December 8th and the vulnerability of the hospital at Fort Stotsenburg located on the edge of the airfield made it untenable and plans were immediately made for the evacuation of patients and the majority or the Medical personnel to the Manila Hospital Center.

The bombing of Nichols Field and the strafing of the McKinley area made advisable the removal of personnel and patients from Fort McKinley Hospital to the Manila Area.

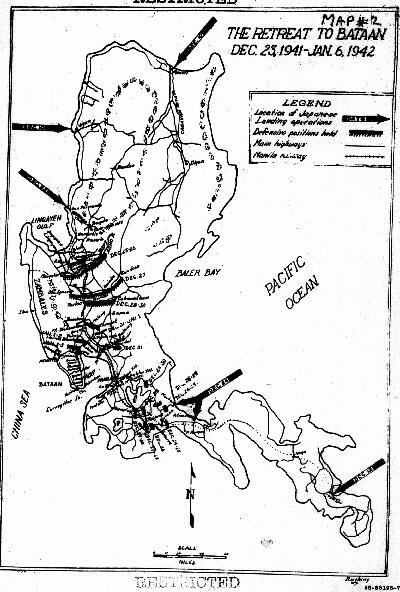

On December 23, 1941, at a Staff conference at the USAFFE headquarters, warning orders were received for the probably evacuation of manila on the following day. The following morning orders were received and late on the afternoon of December 24th the moves to Bataan and Corregidor were begun.

General Hospital #1 was established December 23, 1941 at Limay, Bataan. The Philippine Medical Depot began immediately the removal of medical supplies and equipment. One section of Department Surgeon's Office was established at General Hospital #1 on Bataan and another section at USAFFE headquarters on Corregidor. Later one section of the office was located at the Headquarters Services of Supply, on Bataan with an assistant in charge and the major portion, including all records established in Malinta Tunnel at USAFFE Headquarters on Corregidor. Early in January 1942, a section of the office with an assistant was assigned with the advance echelon of USAFFE on Bataan. Fortunately I was able to keep intact up to that time most of the trained personnel of the Department Surgeon's Office, who did invaluable service when I was, for most of the War, the only Medical Officer available for duty in that office.

Upon the reorganization of the Luzon Force, the following offices were created: The Surgeon, Luzon Force, and Surgeon, Services of Supply.

With the short intensive training given to the Philippine Army medical troops, it was most gratifying to have developed Philippine Army medical officers with an astounding grasp of the details of medical military matters in such a short period of time.

The same remark applies to the enlisted personnel. The majority of them showed an intense concentrated interest in acquiring the detailed knowledge of jobs to which they were assigned.

The delaying action of our troops in the retreat down to Luzon and up from Logaspi and the hesitancy of the Japs in occupying Manila, even when open to them, gave us much needed time in evacuating medical installations and supplies from Manila to Bataan and I recall the almost superhuman activities of the personnel of the Manila Hospital Center and Philippine Medical Depot in accomplishing their task of evacuating personnel, patients and supplies from Manila to Bataan and Corregidor between December 24, 1941 and January 1, 1942; and in performing the enormous task ahead of them in literally hewing out in the jungle of Bataan a future home for the location and operating of General Hospital #1, General Hospital #2 and the Medical Supply Depot.

General Hospital #2 was established at a previously selected site at km. post 162.5 and the medical Supply Depot was located at short distance from General Hospital #1 and #2 at km. post 163.

The 1st and 2nd Corps were pouring down into the peninsula preceded by a vanguard of refugee civilians who added much to the problems of sanitation, evacuation and hospitalization.

The story of the development of General Hospital #2 to a total of 7,000 patients, entirely in the open with the exception of certain facilities, is covered in this report by the Commanding Officer of that hospital during the last months on Bataan.

General Hospital #1 originally located at Limay became untenable as a hospital as the Japs advanced down the peninsula, and that hospital was moved to Little Baguio on January 26, 1942.

About February 15th the pressure on the General Hospitals became so acute that plans were made for the establishment of a convalescent hospital in the Visayas and a tentative location was selected in the vicinity of Iloilo. A nucleus of personnel was selected and brought to Corregidor and prepared for shipment to Iloilo to establish this hospital. The plan of establishing this convalescent camp never was fully executed, however, as the Jap blockade became more acute. The ship which transported the first group of fifty convalescents to Iloilo was sunk by Jap submarines on its return trip from the southern Island. The situation was becoming more serious and no hope remained for relieving the congestion of patients accumulating on Bataan and Corregidor.

With the approaching end of the dry season it was necessary to plan for the removal of General Hospital #2 (about 3,000 beds at that time) out of the jungle to some higher point, also affording shelter of some kind.

This presented no little problem to the Army Engineers, who made a survey with the Commanding Officer of Hospital #2 of the various possible locations. The location selected by the former Chief Engineer, then in Australia, proved to be impossible to develop with the materials at hand and in the time available for construction. The site occupied by the empty Ordnance warehouses adjacent to General Hospital #1 at Little Baguio appeared to be the most practical location although obviously not entirely satisfactory, because of its former use for storage of Ordnance supplies. (For lack of a better alternative, it was finally selected as the best solution of the problem.)

The military situation on Bataan was rapidly becoming worse. The troops were cut to half rationing on January 5, 1942, and were cut to one-third ration in March 1942. Bread was no longer available.

Malnutrition and malaria and effect on combat efficiency. At the time of the fall of Bataan there were approximately 24,000 patients in the hospitals and clearing stations on Bataan. The shortage of quinine had necessitated the limitation of its use for treatment purposes. Malaria, sub clinical in most of the troops on Bataan, superimposed upon a general condition of malnutrition, reduced the combat efficiency to such a point that further resistance was becoming impossible.

Anticipating the fall of Bataan and the need for additional medical supplies on Corregidor, the Medical Supply Depot on Bataan was directed to ship to Corregidor certain critical items of supply to be stored partly in the Malinta Tunnel and partly in medical dumps scattered over Corregidor. A considerable quantity of medical supplies was still stored in the basement of the old Fort Mills Hospital, partially destroyed by shelling and bombing, and unused for hospitalization since the move to Malinta Tunnel after the first bombing of Corregidor on December 29th.

On April 8th, when the fall of Bataan appeared imminent, recommendation was made to the Commanding General, U.S. Army Forces in the Philippines, that all nurses and Medical personnel on Bataan be evacuated to Corregidor on the morning of April 9th. After several anxious hours they all arrived safely at Corregidor. Having watched the blowing up of the ammunition dump on Bataan located between General Hospital #2 and Mariveles, the point of departure for Corregidor, and the delay in the arrival of the nurses early in the morning, made all of us apprehensive for fear that the nurses had been caught in a traffic jam near the point where the ammunition dump was blown up. The arrival of the Bataan personnel, including many of the sick, increased our problem in the already overcrowded Malinta Tunnel.

The Hospital Section of Malinta Tunnel, incomplete at the beginning of the War, was soon made usable and while originally planned to accommodate about 300 patients, at one time was accommodating not only all the patients and medical personnel of Corregidor but furnished quarters and messing facilities to the High Commander and other officials of the Philippines.

Upon the fall of Bataan, as the Surgeon of Corregidor, I took over direct control of all medical activities on Corregidor, in addition to my other duties.

The problem of immediately increasing the bed capacity in the limited space available was difficult, but by double and triple-decking bunks of patients and personnel in the Hospital Section, and by extending the hospital area into the main tunnel and some of the main laterals of the main tunnel, we managed to increase the patient capacity to about 1,000 beds. At no time were we without available beds, but at the time of the surrender of Corregidor there were about twenty vacant beds in the hospital.

Cooking and messing facilities at the tunnel hospital provided for about 300 patients. With an increase to approximately 1,500 patients, personnel and attached individuals, it was necessary to provide additional cooking arrangements outside, near the tunnel entrance. With the increasing intensity of the bombing and shelling during the final days before the surrender, the preparation of this additional food was not only uncertain but a hazardous undertaking on the part of the kitchen force. The Japanese had very accurate range on tunnel entrances.

Laundry. With the destruction of the Quartermaster Laundry, the hospital was dependent entirely upon its own resources for laundry. A number of washing machines had been purchased in Manila for the Manila Hospital Center, and several were shipped to Corregidor upon the evacuation of Manila. Unfortunately, all but two were destroyed by bombing before they reached the tunnel hospital. The constant shelling and bombing in the drying area outside the tunnel made successful laundering practically impossible.

Water Supply. Fortunately, an artesian well near the entrance to the tunnel was never bombed and the hospital was never without a water supply. Often the supply was scant and strict economy in the use of water was necessary at all times.

Sewage Disposal. Frequent damage to sewage disposal lines by bombing or shelling occurred but in very short time repairs would be affected and there was never any long or serious interruption.

Electrical Lighting. With the installation of an auxiliary lighting plant for the hospital area we were never without light except for brief periods.

It was remarkable that in spite of the bombing and shelling over and around the island the responsible authorities could always mange to effect some kind of temporary repairs to keep the public utilities in operation.

Evacuation of casualties from the aid stations throughout the Island of Corregidor was effected under most difficult circumstances due to destruction of roads and frequent shellfire. There were only two ambulances on Corregidor. One was knocked out early in the War but in some mysterious way the other ambulance and driver survived the entire War until the last day of fighting when the ambulance became a casualty. The driver has been decorated with a Distinguished Service Cross for his heroic action and absolute indifference to the hazards of his calls for trips to the various aid stations. Every form of transportation was pressed into service and somehow all casualties would receive transportation of some kind to the tunnel hospital.

There were surprisingly few casualties from air bombing except for when a direct hit was made on air shelters.

During the first artillery bombardment more casualties occurred but the troops soon learned to protect themselves. In the end, however, in my opinion, it was the artillery bombardment that softened Corregidor for the final assault and capture.

The fate of the 1,000 patients, in the event that the fighting continued within the tunnel, was a matter of anxiety to all of us and I shudder to think of the orgy that would have ensured had that fanatical horde actually reached the mouth of the tunnel with flame throwers and machine guns during the final period. After the surrender the Japs demand the evacuation of the tunnel in ten minutes but were dissuaded from carrying out their demand. Fortunately the surrender was effected without any casualties within the tunnel.

No statistics were ever available as to the exact number of the killed and wounded during the final assault and capture of Corregidor. Roughly, I should say that the Japanese casualties in proportion were about ten to one of our casualties. I hope that recovered documents will give a reasonably accurate figure on this matter.

C: Prison Period.

For two or three days after the surrender, the captured duty personnel was being moved to the 92nd Garage Area. Members of the various staffs were being segregated and moved to various places.

The hospital personnel and patients were undisturbed. We were not allowed to leave the tunnel and all communication from the outside was cut off.

Finally permission was granted to me to go to the Headquarters of the Jap Forces and arrange for disposition of the dead in the tunnel and shortly afterwards liaison was established with the Surgeon of the Jap forces. With this officer the general situation was discussed -- the matters of sanitation, the generally unsatisfactory conditions and the potential danger of an epidemic of dysentery among the troops crowed in the 92nd Garage Area.

I requested to use other campsites on the Island to relieve overcrowding. He appeared to be anxious to do what he could but was simply overwhelmed and unable to do anything definite about it. Finally he became exasperated and made a remark that has remained with me as a clue to the Japanese treatment of all prisoners of war: "I realize" he said, "that these conditions don't suit you and your people, but you must remember this -- you have been captured by a nation whose standards in such matters are lower than yours." Definitely lower as we found during our subsequent experience. So low, in fact, that the matter of elemental sanitary arrangements and basic human needs in our various camps were matters of utter indifference to most of the responsible Japanese medical authorities.

After the initial period of confusion on Corregidor, relatively satisfactory relations were established with the Japanese authorities. The hospital routine was allowed to continue. There was a lot of coming and going and curious prowling around the hospital by Japanese officers and enlisted men. The Japanese doctor in charge proved to be a courteous, considerate individual and cooperated with me as he said "50-50." A couple of Jap soldiers were brought into the tunnel hospital and operated upon by him with assistance of our operating surgeon. He gave me a pass to go unmolested throughout the Island. The Jap Commander at Corregidor visited the hospital, expressed great concern over continuing to keep all the patients in that "hole in the ground." He cooperated with me fully in making arrangements to get patients and personnel out into the sunshine that some had not seen for months. He expressed the greatest solicitude over caring for the nurses and women in the tunnel. He authorized and urged the speedy repair of the old Fort Mills Hospital near Topside for use again.

In an inspection of the old hospital by an American officer, Corps of Engineers, he expressed his opinion that repair and use of the old building was not only possible but that it could be made usable in a comparatively short period.

A large part of the roof of the hospital had been destroyed. Some parts of the roof were reparable, and the second floor (concrete) was fairly intact and could be used as a roof for the first floor. The kitchen and basement storeroom were in fair shape.

By July 25th, 1,000 patients in the tunnel had been reduced to about 400. The overhead personnel of the hospital had been reduced proportionately. The Japanese supply officers issued to the hospital at one time shortly after the surrender, rations for one month's supply. This ration according to our analysis had a caloric content of about 2,000 calories per man per day.

The Japanese doctor requested that he be furnished an analysis of food requirements for patients and other suggestions for improvement.

During this period, among the other Japs to visit the hospital and consult with me about the food situation and ask for suggestions about improving our food supply, was General Homma. He was courteous and apparently interested. This visit was made just after the infamous Death March on Bataan ordered by General Homma and during the period that our fellow prisoners of war at O'Donnell and Cabanatuan were dying at an alarming rate from dysenteries, dietary deficiencies and general neglect of the elemental human needs.

During the period between the fall of Corregidor and the move from the tunnel to the old hospital on June 25th and during the period when the mortality rate was the highest among the prisoners of war at other camps in the Philippines as a result of neglect and apparent indifference on the part of the Japanese authorities and in spite of a threatened epidemic of dysentery arising in the 92nd Garage Area, the deaths among the prisoners of war on Corregidor were only twenty-six and most of these were battle casualties.

Fortunately during the last few days before the surrender of a few essential medical supplies, including some sulfathiazole and carbarsone had been brought in by air through Mindanao.

There were medical supplies in the General Hospitals and Medical Supply Depot on Bataan and in the abandoned hospital and depot in Manila to meet all the requirements of our needs and more, but either through indifference or premeditated plan our prisoners of war at most other camps were almost totally lacking in the most necessary medical supplies.

At Corregidor I was allowed to retain control of all medical supplies. We had many more supplies than the Japanese themselves. The Japanese doctor would request certain items from my hospital (if I could spare them) and would meticulously sign a receipt for every item furnished.

Either I or some of my assistants would attend a conference in the office of the Japanese doctor daily, at which time he would request detailed reports concerning the patients and the hospital.

Various delegations visiting the hospital were continually curious about the number of our casualties and expressed surprise and incredulity at the relatively small number of our casualties as compared to their admitted losses. I could never make them believe that we were not, in some way, keeping back from them the true figures of our losses and finally they accused us of throwing our dead into the sea for disposition.

On June 25th, the movement out of the tunnel into the marvelous atmosphere of the renovated old hospital was completed. A holiday atmosphere prevailed all over the place. We all had an "it's good to be alive" air about us. We had obtained a piano from the Japanese from some source. We had secured a radio. We were sending out parties throughout the Islands for green stuff to eat.

We had a visit from the Surgeon General, Japanese Army, and apparently as a result of his visit to the Philippines, it was decided to move us. On July 2nd at 9:00 AM, I was called to the office of the Japanese and told that he had just received orders for our removal to Manila and that all patients and personnel, except the nurses, would be loaded on a freighter in the harbor by 4:00 PM that day; that no hospital beds would be moved as plenty were available where we were going.

Accordingly between 9:00 AM and 4:00 PM we loaded all the patients, personnel and supplies that we possibly could handle. I was directed to remain in the hospital overnight and accompany the nurses to the ship the following morning.

The Japanese Commandant, during the short period in which we occupied the old hospital, had given positive instructions that no Japanese soldier or any visitors from off the Island would be allowed to enter my hospital without his personal permission. He visited the hospital the night before we left - presented the staff with a large iced cake of which he was very proud, some small cakes and some beer.

During this period at Corregidor, while many things came up that were disagreeable and almost intolerable, yet in the main I got the impression that back of it all there was an intention and effort on the part of the Japanese to observe the decencies and general provisions of international law outlined in the Geneva convention.

I arrived in Manila on the morning of July 3rd, expecting to reassemble patients, our personnel and equipment and supplies in some appointed place in Manila. Then much to my surprise and disappointment, upon arrival in Manila, the nurses were sent to Santo Tomas. I never saw or heard of them again until after I was released this year. I was sent to Bilibid Prison with no further connection with the patients. The patients and equipment were admitted to the Hospital Section of Bilibid -- then being run by the Navy medical Department.

After remaining at Bilibid Prison for a week, I was sent to Tarlac to join General Wainwright and other senior officers for transfer a month later to Formosa in accordance with what was apparently a studied policy of the Japanese to provide for a separation of the senior officers from the lower ranks. I never gave them credit for removing us from the Philippines as a result of any solicitation among the higher-ups concerning our health and the effect of long remaining in a tropical climate. Our later treatment at our destination in Karenko proved that they had no special concern over our physical welfare. At Bilibid and later at Tarlac where I remained for one month, I learned for the first time of the horrible experiences of the Death March and prison camps O'Donnell and Cabanatuan. Many of the Tarlac group were survivors of those horrible conditions and it was a feeling of guilt almost that my experiences up that time had been so relatively humane.

Our trip to Formosa, while crowded in the double decker quarters in the hold of a troopship, was not unbearable. The food was better than it had been at Tarlac and our treatment en route to Manila, while in Manila and on board ship was not so bad.

We arrived in Takao Harbor on August 14th -- transshipped to an inter-island boat and finally arrived at our destination at Karenko on the east coast of Formosa on August 17th 1942.

We were exhibited to an enormous crowed of natives in our long hot march to our camp, subjected to a rigorous shakedown inspection on our arrival, but we at first considered our accommodations and general arrangement for our care, to be an improvement over our conditions in the camp that we had left in the Philippines. Karenko is just on the edge of the temperate zone and the climate in the main is delightful most of the year.

The story of Karenko is too well known to need repeating here but insofar as treatment is concerned it was the low point for our group.

We were not only told, but shown by our treatment, that we had no rank. We were worked on the farm -- marched out and back by armed guards. We were subjected to every possible indignity. We were beaten and disciplined for the last infraction of petty regulations. We were starved by what would appear to have been a deliberate aim on the part of the Japanese authorities to keep our physical condition down below a certain physiological level.

We were fed propaganda papers freely during this period, filled with the wildest, unrestrained and imaginative reports of Jap victories and allied defeats. Our navy was being sunk regularly. Exact figures were given about once a month and written carefully on a blackboard for our perusal. A corresponding report showed relatively slight Jap losses.

Still with all this physical and mental punishment, the spirit of the group remained as a whole unbroken. The majority of the group lost from fifty to seventy-five pounds in weight. Some individuals halved their weight. Practically everyone had a nutritional disorder of some kind. Nutritional edema was the rule.

As a relief to this impossible situation and what appeared to be a deliberate starvation policy, some British Red Cross supplies in fairly liberal quantity arrived. As an additional tantalizing gesture the supplies were brought into the camp and stored for a long period before the details of method of issue could be worked out by the Japanese authority. The final issuance of these supplies spread out over a period of several weeks actually saved the lives of many of our group and never afterwards were we so hopelessly underfed over any such extended a period. At subsequent periods we had occasional times when the "heat was turned on" with its accompanying starvation diet but not over such a long and seemingly never-ending period.

The feeding of prisoners of war was somehow involved in an overall directive from the highest Jap authorities concerning the production of food and its relation to work. At all camps there appeared the same farming idea, the raising of pigs, chickens, rabbits and even bee culture was considered. At one of our camps there seemed to be some kind of recognition on their part, that the laws of War forbade the working of certain ranks on projects requiring manual labor, etc. Still this other directive required everyone to work. With a typical oriental mentality, they attempted to evade meeting the issue squarely by using every artifice at their command to comply with both directives. They evolved the ingenious expedient of "enforced volunteering" for farm work of the majority of our group. This continued in the development of two farm projects, one at Karenko and the other at our second camp in Formosa, Shirakawa, from neither of which farms did we ever derive any substantial returns. We moved away from the first farm before any produce had matured. At the second place, Shirakawa, the working condition there apparently had percolated through to some higher responsible authorities. We had a visit from the Senior Camp Commandant of Formosa and an attempt on his part to have us sign an agreement that we had volunteered for the farm work we had already been required to do -- this the group almost unanimously refused to do with the result that the pressure was applied in real force. We were cut off from all farm produce, with a general reduction in our food; we were awakened several times nightly for roll call; amusements of all kinds were restricted to Saturday afternoons and Sundays. They allowed no naps in the afternoon; neither were we allowed to lie on our bunks or even sit on bunks or to take a nap in any position during the daytime.

Several officers were placed in the guardhouse on rice and water diet for four to ten days for petty infractions of regulations. We were in constant fear of "bopping" by several fanatical underlings who were apparently encouraged in their sadistic impulses by the camp authorities.

This condition of affairs continued over a long period, during which time the Japanese propaganda papers ceased to arrive and good rumors began to trickle into camp, when suddenly on October 1, 1944, all the general officers in camp received emergency orders to leave the camp by air for a colder climate. Shortly after their departure, we received underground rumors of our air attack on Manila. On October 9th, all of the colonels were hurriedly moved by train to northern Formosa to Keolung, the harbor of Taihoku, and there loaded onto a large Japanese liner and packed like sardines in the hold of the ship and, just as we were about ready to sail two days later, we noticed a sudden unloading of all the other passengers on board including many Japanese wounded and civilian refugees. Soon afterward we had the mixed emotion of seeing and hearing our own aircraft in action for the first time in two and one-half years.

Luckily, our ship, the largest in the harbor, was not bombed but after a delay of two weeks we finally sailed and arrived safely in Japan five days later. I understand that this same ship was bombed on the next trip and sunk off Subic Bay with the loss of many prisoners of war aboard.

After two weeks at Beppu, a Japanese Hot Springs resort in Northern Kyushu, our part was moved across to Fusan [Pusan], Korean, and on to Central Manchuria, about 150 miles north of Mukden and spent the winter of 1944-1945.

An attempt by the local Jap Commandant at "enforced volunteering" for work failed completely. We were getting underground news in the form of a Japanese newspaper translated by a Japanese language officer. We knew the progress of events. This paper gave the full news to the local populace. The extent of the news would indicate that the news given to the people was defeatist propaganda building up the people towards a final surrender of Japan.

We were not surprised therefore when the end came. Actually some of our group (of which I was one) were more optimistic than those "in the know" on the outside had reason to be.

Addenda. In the Bataan and Corregidor siege, shell shock (battle fatigue) presented no serious problem. There was no possible retreat from reality. On the rock there was no room for such cases in the tunnel, so arrangements were made to send a few cases to Bataan.

Among the troops brought over to Corregidor at the fall of Bataan, a high incidence of malaria soon developed among those individuals who had previously kept their infections subclinical during the time that quinine was available for repressive use. After the discontinuance of quinine an alarming number of cases developed on Corregidor. This was quickly brought under control by treatment of infected cases and repressive doses of quinine to all the troops from Bataan. Undoubtedly the same thing happened to the Bataan troops forced to march out of Bataan and in the absence of sufficient quinine for treatment and repressive use, malaria superimposed upon the general malnutrition, must have accounted for a large percentage of deaths on and following the march from Bataan. There was considerable quinine available in our medical installations captured on Bataan which the Japanese would not make available. Every effort was made by our captive medical personnel to persuade the Japanese authority to obtain and use these supplies among our neglected dying comrades to no avail.

My medical supply officers was sent to Manila for the purpose of assisting the Japanese medical authorities in searching through and obtaining for them the necessary supplies from our captured depots. I was never able to see and discuss with him the success of his effort in getting these supplies out to our captured troops.

In the light of the subsequent treatment of all prisoners of war, including Medical Department personnel, Chaplains and Red Cross workers themselves, I recognize now as naive my unsuccessful attempt to obtain contact with the head of American Red Cross in Manila with the idea of obtaining through him some kind of credit for obtaining some relief supplies.

When my supply officer went to Manila to assist the Japanese in the distribution of medical supplies, I had hoped that he would be able to make contact with the Red Cross Representative.

While the overall characteristics of the Japanese may be outward politeness and inward cunning and deceit, still I gained the impression of sincerity in my dealing with the Japanese doctors on Corregidor. My disillusionment was complete, however, from the time I entered Bilibid Prison until my arrival at Mukden in the spring of 1945.

3. THE MEDICAL FIELD SERVICE, PHILIPPINE CAMPAIGN.

World War II was a global war involving activities in almost every corner of the world under almost every conceivable condition of climate and terrain; a war characterized by the introduction of many new weapons and by tactical extremes varying from a bull-dog-like hold onto a tiny bit of land to vast movements of almost unbelievable speed and extent. In a war of such protean character, the Medical Department of the U.S. Army was faced with many a situation for which no adequate precedent existed to serve as a guide in solving the medical problems which arose. Such solutions often involved marked modification of the accepted dogma of medical tactics. Such deviations from standard routine give added interest to the medical history of this War and it is because of this that the chronicle of the Philippine Campaign finds justification; that along with tragic fact that about 40% of the Medical Department personnel who participated in this opening phase of World War II did not survive to witness the final defeat of Japan.

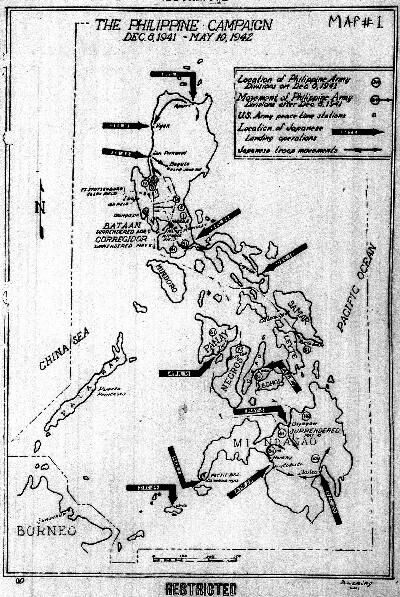

The subject matter relating to the field medical service of the Philippine Campaign can very conveniently be divided into three phases: a pre-war period of preparation; the initial stages of the campaign, including the withdrawal of the American forces to Bataan; and the Bataan Campaign. This section of the general report will be confined to those military operations which took place on the Island of Luzon and will not touch upon the medical service of the harbor defenses of manila Bay or the relatively minor events which occurred in the Southern Islands. These will be covered in separate sections of the general report.

A. Pre-war Period of Preparation.

Prior to 1941, the U.S. forces in the Philippines consisted of the Philippine Division, the 31st Infantry (American) and the Coast Artillery units garrisoning the Harbor Defenses to Manila Bay. The Philippine Division at this time consisted of 4,000 highly trained native troops. There is a general agreement among those officers who have served with this unit that no finer soldiers ever wore the American uniform. They were well disciplined, their spirit de corps was of the highest quality and their noncommissioned officers were men of long service, carefully selected for their reliability, their administrative ability, and their qualities of leadership. Intense loyalty characterizes the Philippine Scout. In no element of the Philippine Division were these qualities more highly developed than in the 12th Medial Regiment (PS). Although it numbered but two hundred members prior to 1941, yet in a broad sense the history of the field medical service of the Philippine campaign is largely that of the activities and influence of this small Regular Army medical unit. In many respects this organization is unique in the annals of the medical military history of the United States for it is doubtful if any unit of similar size has ever contributed so much to the medical service of a major campaign.

The defense forces of the Philippine Commonwealth consisted of one skeletonized regular division, the Philippine Army, and a police force known as the Philippine Constabulary. The Philippine Army was a conscript army, the personnel of which had received a five-months course of basic training within the past five years prior to the War. After this period of training, they were placed on a reserve status and assigned to one of the ten small divisions into which the Philippine Army was organized. Certain of the noncommissioned offices had participated in two or more such training periods. The commissioned personnel consisted of relatively untrained reserve officers. A few of the officers had seen service in the Philippine Constabulary. The Philippine Army Division is a small triangular division and as such contains a medical battalion and the usual attached medical personnel. (In the Philippine Army the medical detachments to infantry regiments were called medical companies.)

During the year prior to the onset of the War, the 12th Medical Regiment (PS) was engaged in the following activities:

(1) War Plans. The officers and men of this medical unit participated in all maneuvers and reconnaissances of the Philippine Division (PS) with a view towards perfecting the medical sections of war plans relating to the defense of the Philippines. A final period of intensive reconnaissance work occurred in the period from November 1940 to February 1941. At this time medical installations for the two major defense positions in Bataan we relocated, as were sites for rear-area general hospitals. The value of such detailed planning prior to war is too self-evident to require comment.B. Withdrawal to Bataan. (December 8, 1941 to January 7, 1942.)

(2) Recruit Training. In January 1941, authorization was obtained to increase the Philippine Division from 4,000 to 8,000 Scouts. The 12th Medical Regiment doubled its organizational strength at this time. An intensive training program was inaugurated and so successfully carried through that by December 1941 this increment consisted of thoroughly trained medical soldiers, both technically and spiritually prepared for active service.

(3) Medical Detachments. Prior to August 1941, only those units of the Philippine division stationed at Fort Stotsenburg where provided with authorized medical detachments. All other units were dependent upon personnel from the 12th Medical Regiments (PS). The seriousness of this gap in the medical service of the Philippine Division was brought to the attention of the Commanding General, who in May 1941 gave authorization to select and train cadres for all units stationed at Fort William McKinley. This training was carried out by personnel of the 12th Medical Regiment, these cadres later becoming the nuclei around which the medical detachments of these organizations were formed. Personnel to fill the key noncommissioned officer positions in these newly formed detachments was furnished by the 12th Medical Regiment.

(4) To augment the medical service to the 45th and 57th Infantry (PS) their regimental bands were trained in first-aid work and litter bearing during the summer of 1941.

(5) Philippine Army Training School. Acting under instructions from the Surgeon, H.P.D., the 12th Medical Regiment operated a training school for the officers and noncommissioned officers of all Philippine Army medical units from September 1, 1941 to December 1, 1941. The subject matter embraced all phases of division medical service and included elaborate field exercises. The value of this training course which was attended by some 1,300 officers and noncommissioned officers from all ten Philippine Army divisions and completed just one week before the opening of hostilities was immense. For the majority of the Philippine Army medical officers and non-commissioned officers, this three-months' training school was their only serious, comprehensive training prior to the War. The impress of the 12th Medical Regiment, its spirit and morale, was left upon every medical unit of the Philippine Army. It is to be regretted that after these officers rejoined their recently mobilized organizations, no opportunity was afforded for unit training prior to the War. The first tactical participation of these Philippine Army medical units occurred under grim real battle conditions after the invasion of the Philippine Islands.

(6) Reorganization of Philippine Division. In August 1941, the Philippine Division reorganized as a triangular division the 12th Medical Regiment now becoming the 12th Medical Battalion with Companies A, B and C Collecting and Company D Clearing. One collecting company was attached to each of the three combat teams of the Division. This arrangement continued throughout the campaign. The medical units of the Philippine Division took the field on December 8, 1941, with approximately two-thirds of their T/O strength in respect to both officers and enlisted men. Only the key positions were held by Regular Army officers, the balance being made up of recently arrived reserve officers. The reorganized 12th Medical Battalion functioned smoothly and efficiently throughout the entire campaign. In Bataan it became a medical task force.

Equipment and Supply.

(1) Medical Units of Philippine Division. These units took the field on December 8, 1941, with largely improvised equipment made up of old, revamped, 1917-type medical chests. In the spring of 1941 request had been made for entirely new-type equipment for medical battalions and medical detachments. Every effort was made by the Philippine Department Surgeon to procure this equipment but no large shipments were received prior to the onset of hostilities.

(2) Philippine Army Medical Units. These units were practically complete in organic equipment according to their T/O. This consisted almost exclusively of simple medical field chests and included no tentage. Practically no reserve of medical supplies was carried by the Philippine Army and consequently these units were entirely dependent upon the Philippine Department Medical Supply Depot for replacement of items of all classes of medical supply during the campaign. The most serious deficiency in the organization and equipment of the Philippine Army medical Battalions was the absence of a laboratory section in the Clearing Company. The microscope was not an item of equipment which meant that in Bataan these medical units were seriously handicapped in their efforts to control and treat intestinal infections and malaria.

(3) Transport. On December 8, 1941, medical units of the Philippine Division were equipped with only about 25% of their organic transportation. This deficit was made up by the use of civilian taxis, trucks and buses. The Philippine Army was entirely dependent upon such vehicles.

The defense force of Luzon on December 8, 1941, consisted of the Philippine Division (PS) and nine partially mobilized Philippine Army divisions whose strength varied from 4,000 to 6,000 each. Two forces were organized, a "North" and a "South" Luzon Force, whose mission it was to meet and defeat the enemy at the beaches. The Philippine Division was placed in a reserve position in Bataan. During the month of December, 1941, the enemy made a series of landings on both north and south Luzon, driving the defense forces back toward Manila. This phase of the campaign consisted of a series of delaying actions. In many respects this opening phase of the War can be looked upon as a period of intensive training for these medical units. Very few battle casualties were sustained in the course of the withdrawal. The sick and wounded who were unfit to accompany their units to Bataan were left in civilian medical facilities for care and treatment. Relatively few cases where evacuated to the General Hospital Center in Manila.

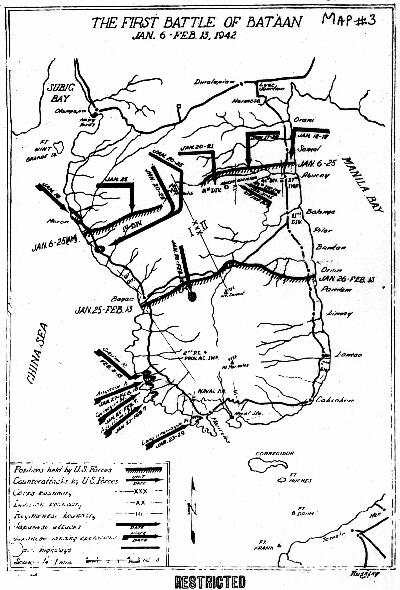

As soon as it became certain that a Bataan campaign was inevitable, every effort was made to evacuate medical supplies from all sources to Bataan. In late December, 1941, a surgical hospital was established at Limay, Bataan and a general hospital was set up on a site near the Real River about two kilometers west of Cabcaben. (See map #3) Both installations were ready to receive patients on January 7, 1942.

C. Bataan Campaign (January 7, 1942 to April 9, 1942)

On January 7, 1942, the American forces completed their withdrawal to the Bataan peninsula and established themselves along a defense line running roughly from Abucay to Moron. (See map #3) The enemy held the base of the peninsula and controlled the water approaches by reason of his sea and air power. No additional supplies in sizable quantities could now be obtained. Self-sufficiency was imposed upon the defense forces from this date. Consumption without replenishment became the distinguishing feather of this campaign. A defeat due to attrition alone became inevitable.

Existing War plans had called for a force of some 30,000 men for the defense of Bataan and had stressed the necessity of evacuating all civilians from the area in the event of war. On January 7, 1942, the American force in Bataan consisted of 78,000 military and 6,000 civilian employees (used largely as laborers). This amounted to a total of 84,000 men, or a force almost three times as large as that called for in War plans. In addition there were between 25,000 and 30,000 civilians in Bataan who were largely dependent upon the defense force for food and medical supplies. Both of these classes of supply were totally inadequate for a population of 11,000. This civilian population imposed an extra burden upon the Medical Department which assumed responsibility for their care and treatment. The small staff of Filipino Doctors and Nurses from the provincial hospital at Balanga Bataan, were of great assistance in caring for these people.

A most serious situation existed in the matter of supply because of the fact that many units of the Philippine Army had reached Bataan with an inadequate supply of organizational and individual equipment. These troops had not received proper training in property responsibility and the importance of conservation of supplies. A considerable quantity of their property was abandoned during their withdrawal to Bataan. Many of these troops in combat positions had only the scanty clothing worn by them during the withdrawal. A large percentage were without shoes, raincoats, blankets, and shelter halves. The Philippine Army was not equipped with individual mosquito bars. Moreover, there was little or no tentage. Inasmuch as the defense line in many places ran through mountainous terrain, where the nights were quite cool, considerable hardship resulted. These shortages were of vital import in reference to the incidence of malaria, hookworm and respiratory diseases. Reserve stocks of these items which might have made up of such deficiencies did not exist. Stringent rationing of all classes of supply was put into effect, the most serious restrictions being placed on food. All troops on Bataan were placed on half rations on January 7, 1942. Further reductions were made periodically in order to prolong the period of defense.

The medical service of the Bataan Campaign will be considered in three phases, corresponding to the two major defense positions occupied and the final drive of the Japanese terminating in the capitulation of the American forces.

(1) First Defense Position. (January 7 - 26, 1942) (See map #3) Inasmuch as lines of communication determine hospitalization and evacuation plans, consideration must here be given to the existing road and trail network of Bataan on January 7, 1942. (See map #3) Hugging the eastern shoreline of Bataan, an all-weather two-way road known as the "East Road" runs from Lyac Junction to Mariveles. From Cabcabin north this road follows a fairly level course along the bay shore. The road from Mariveles to Moron is known as the "West Road." It is an extremely tortuous road cut through dense jungle into the steep sides of the main mountain mass of Bataan. In many sections it is open to one-way traffic only. The work of widening, straightening, and surfacing this road was under way when the war began. The only connecting link between the "East" and "West" roads is the Pilar-Bagac road which crosses the peninsula through a low saddle between the north and south mountain masses. This is an all-weather, two-way road. Except for a few old logging roads in an extreme state of disrepair, no other roads existed in lower Bataan at the onset of the campaign. On the east side from Orion north there is an agricultural area extending inland toward the mountains for several kilometers. A number of narrow secondary roads penetrated this area. This is the only section of Bataan of any size that is under cultivation. Jungle conditions characterize all other areas. A number of trails, mostly heavily overgrown, penetrate the jungle. The jungle is practically impassable, except for these trails. The flora is largely tropical timber with an undergrowth of small shrubs densely matted together by the intertwining vines.

The first Battle of Bataan was fought along the general line of Abucay-Mt. Natib-Moron. (See map #3) From the eastern shore west to the Abucay hacienda the line passed through level, open country consisting largely of rice fields. From this point west the terrain is very mountainous with jungle conditions obtaining.

In view of the location of the two general hospitals along the "East" road, the line of evacuation for both corps was down the "East" road, using the Pilar-Bagac road for cross communication.

The heaviest fighting occurred on the right of II Corps in the areas of the 57th Infantry (PS) and the 41st Division (PA). An old church with massive stone walls in Abucay proved ideal for a combined regimental aid and collecting station for the 57th Combat Team. A similarly constructed church and the Provincial Hospital at Balanga were utilized by the 41st Medial Battalion (PA). The collecting companies operated forward ambulance service direct to the various regimental aid stations as far inland as the hacienda. Inasmuch as these routes were frequently under heavy artillery fire and were also exposed to aerial bombardment, the work of the ambulance drivers was especially worth of commendation.

Every effort was made during this engagement to keep all division medical installations in a state of high mobility by rapid evacuation since it was considered likely that a withdrawal to the reserve battle position might become necessary at any time. With this in mind, all but the very minor cases were evacuated by the collecting companies direct to the general hospitals. A system of Army evacuation was not in effect at this time. Because of the short distances involved, this arrangement was entirely satisfactory.

The enemy made two serious break-throughs of this initial battle position. On January 205h, they penetrated the area of the 51st Division (PA). During the precipitate retreat that followed the medical companies (medical detachments) lost a large portion of their equipment when they were deserted by their line troops. On January 24th the Japanese infiltrated behind the position of the 1st Division (PA) and established themselves on the road south of Moron, thus cutting the only line of communication of this division. The only avenue of withdrawal lay along the beach and conditions were such that very little equipment could be carried out of this route. During the nights of January 24th and 25th there was an organized withdrawal to the reserve battle position.

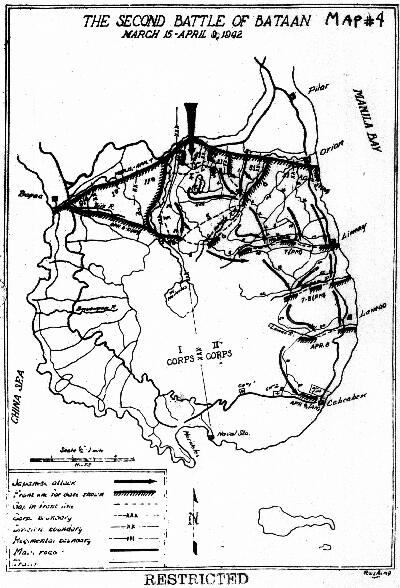

(2)Second Defense Position.(January 26 to April 2 1942) (See map #4). The new defense position ran roughly parallel to and slightly below the Pilar-Bagac road. An entirely different situation now existed in regard to evacuation. The Pilar-Bagac road, the only highway connecting the "East" and "West" roads, was now denied to us and could no longer serve as a channel of evacuation. Traffic was now limited to the coastal highways.

South of the Pilar-Bagac road, Bataan is roughly a gigantic volcanic cone, the sides of which rise abruptly from the shoreline to form Mt. Mariveles. The slopes of this cone are ribbed with deep ravines formed by rapidly flowing mountain streams, the natural habitat of the malarial mosquitoes. The entire area is clothed with a dense luxuriant tropical growth which offers unlimited cover. To traverse the country in an east-west direction along the new position was a slow and arduous process of clambering in and out of these deep ravines which in this section radiated like the ribs of a fan from the summit of Mariveles Mountain towards the Pilar-Bagac road. A few old, overgrown mountain trails existed in this area. These were the sole means of access to the major portion of the defense line.

In I Corps there existed an old logging road. (Trail #17) running roughly along the regimental reserve line which was available for the services of evacuation and supply after repairs had been affected. Three clearing stations we located along this channel. The area was within easy artillery range and was frequently shelled, but fortunately these medical installations received no direct hits.

In II Corps, by January 26th, the Engineers had broken a crude road along trail #2 (See map #4) as far as the San Vicente River. Beyond this no means of communication existed save by foot trails which at this time were in a state of extreme disrepair. The 41st Division (PA), 21st Division (PA) and the 33d Combat Team (PA) occupied this inaccessible area extending from the San Vicente to the Pantingan River. It was obvious that the medical installations serving these units must be self-sufficient, and that no evacuation would be possible for a considerable period of time. One American officer and one NCO of the 12th Medical Battalion (PS) were assigned to each of these three Philippine Army medical battalions to assist them in setting up their division medical installations with only such equipment as could be hand packed into this area over difficult mountain trails. After three days of arduous trail work all units were in position. The clearing companies of the 41st and 21st Medical Battalions (PA) constructed from jungle materials 400-bed field hospitals. A 150-bed installation was set up for the 33d Combat Team. The Filipino soldier displayed unbelievable ingenuity and skill in the construction of these clearing stations. After the dense undergrowth had been cleared away, bamboo frames were erected, on which patients were placed. These were covered in order to give protection from the weather. No tentage was available. Cover was so perfect that low-flying planes were unable to detect the presence of these field hospitals and one could pass within a few yards of them in the jungle without being aware of their presence. All necessary medical and surgical procedures were carried out in these jungle hospitals. Cases were quickly returned to a duty status. Time lost from illness and injury was reduced to a minimum. The 21st Clearing Station operated for three weeks before evacuation became possible over newly constructed roads, the 41st Clearing was without evacuation for six weeks and the 33d Clearing for a period of two months. An excellent description of the type and quality of medical work performed by these organizations is contained in the following letter of appreciation which is quoted in full:

There is no intent here to single out any particular medical unit for special mention. Mention has been made of these three Philippine Army medical units only as an illustration of the character of medical work that typified all organizations in Bataan. The efficiency with which these recently mobilized and relatively untrained Philippine Army medical units functioned is a tribute to the courage, fortitude and ability of the Filipino. Improvisation was a necessity and was exercised with a high degree of originality and invention. A bare minimum of medical and surgical equipment was available. There were serious shortages in all classes of supplies; food, clothing, blankets, and medical supplies.HEADQUARTERS SUB-SECTOR "D,"SUBJECT: Appreciation

II CORPS

In the Field

March 5, 1942

TO: Surgeons

21ST Division (PA)1. Please convey to your officers and men my sincere and deep appreciation of the splendid medical service provided your respective units during the trying circumstances incident to the occupation and organization of this sub-sector. The extreme difficulties attending the establishment, operation and supply of your medical installations in the absence of any means of transportation except foot and pack trails is fully appreciated and understood by me. Your officers and men are deserving of the highest praise and commendation for the speed and efficiency with which the wounded have been evacuated by hand litter over difficult trails and under fire from almost inaccessible areas of the Out Post Line. The work of the medical personnel accompanying patrols has been an exhibition of the highest courage and a major morale factor in the operation of these patrols. It is extremely gratifying to me to know that when circumstances prevented evacuation of your casualties to Rear Echelon medical installations, a condition which characterized this sub-sector for several weeks after its occupation, you have shown the capacity to be self-sufficient within your area and from your meager and improvised equipment have been able to provide the essentials of medical and surgical care to your patients. The continuation of this policy of treating all but the more seriously wounded and ill, now that evacuation is possible, is very commendable in reducing the number of duty days lost. The absence of epidemics within your units is a direct index of the efficiency of your medical inspectors.

41st Division (PA)

33d Combat Team (PA)

2. I take great pleasure in extending to you and your medical personnel this expression of appreciation of your splendid performance in keeping with the highest quality of medical tradition.

Maxon S. Lough

Brigadier General, U.S. Army

Commanding

The work of the medical companies in evacuating to the battalion aid stations and evacuation from the collecting companies to the clearing stations was a most arduous procedure which involved hand carrying up and down steep and narrow trails. The work of these units is especially noteworthy when cognizance is taken of the act that during the campaign the ration varied from 2,000 to 1,000 calories per day. All personnel suffered great loss of weight with serious muscle wasting. Attempts were made to utilize the carabao and the native ponies for evacuation purposes but both animals were found to be unsuitable. Medical personnel accompanied all patrols operating beyond the Outpost Line of Resistance. The type of medical service furnished was no small factor in the maintenance of high morale among the combat troops. The Red Cross emblem was not displayed over any division medical installation.

The following typical report was rendered by the Surgeon of the 21st Division (PA) regarding the operation of a division medical service in Bataan. Of the three organizations mentioned above, this unit was most favorably situated as far as accessibility was concerned.

The above is illustrative of the problems that faced these relatively untrained Philippine Army medical organizations.United States Army Forces in the Far East

Headquarters, 21st Medical Battalion (PA)

In the Field

March 14, 1942

SUBJECT: Medical Service of the 21st Division (PA) from Jan. 26, 1942 to March 1, 1942

TO: Surgeon, Sub-sector "D," II Corps. In the Field

In compliance with the letter from that office, dated March 6, 1942, the following report on the medical service of the 21st Division (PA) during the period from Jan. 26, 1942 to March 1, 1942 is hereby submitted.

1. The Clearing and Collecting Companies of the 21st Medical Battalion arrived at the area assigned to them on Mt. Samat by hiking up the mountain on newly opened trails, each man carrying his meager personal baggage and as much medical equipment as he could carry on his shoulders or on opened litter. Because of the difficulties of transporting everything by man carry, all non-essential equipment were left at Lama where the Headquarters Company was left to watch them. After locating good sites and establishing our stations, the problem that confronted us was the transportation of casualties from the Collecting Stations to the Clearing Station. As the only means of communication was by foot trails, there was no alternative but to carry them by litter. Fortunately, the 21st Infantry was held in reserve and the "A" Collecting Company did not have to function as such. This company was then utilized to carry the casualties from the "B" and "C" Collecting Stations to the Clearing Station. Another problem was the impossibility of evacuation from the Clearing Station because of its inaccessibility to ambulance.

On March 5, the 21st Infantry was assigned a sector at our front. The "A" Collecting Company had to move and establish a Collecting Station at the rear of this regiment. This station is now very far from the other Collecting Stations and the Clearing Station.

To solve the problem of evacuating the casualties from the "B" and "C" Collecting Stations after the "A" Collecting Company had moved, one platoon of the Clearing Company established an advance Clearing Station near these Collecting stations to take care of casualties right there without having to evacuate them to the main Clearing Station. Only serious cases and those requiring elaborate treatment are so evacuated.

Evacuation within the division has been an arduous task, both from the standpoint of human energy and time required. Litter routes are long and tedious, going up and down hills, along trails rendered difficult by big stones and obstructing vines. All available men of the Collecting Companies are utilized as litter bearers. Some men of the Headquarters Company and the Clearing Company are attached to the Collecting Companies to increase the personnel of the latter. It takes about three hours from the time a casualty is tagged to the time he arrives at the Collecting stations and around one hour from the Collecting Stations to the Clearing Station. Undoubtedly this difficulty will be considerably increased during the rainy season when the trails become muddy and slippery.

Because of the difficulty of evacuation, it has been our policy to retain as many cases as possible not only at the Clearing but also at the Collecting Stations, evacuating only those cases requiring medical and surgical attention obtainable only at the rear. This policy has been made possible by the relative inactivity at the front.

2. Supplies. Medical installations are short of litters and blankets. Woolen blankets are especially needed for casualties who are more or less in a condition of shock. The latter condition is usually associated with severe hemorrhage. Casualties in this condition are not fit for immediate evacuation and much good can be done to tide them over a critical period if they are given hypodermoclysis or venoclysis. Many lives would have been saved if these were available on time. The Clearing Station should have the apparatus and solutions for this purpose in sufficient quantity. Hemostatic drugs are also suggested. Surgical equipment is incomplete; there is no adequate sterilizer and many instruments are lacking. The necessity for adequate surgical equipment in the field cannot be overemphasized especially in view of the difficulty of evacuation to the rear.

* * * * * * * * * *

8. Special Problems in Sanitation and Epidemiology: Many cases are brought to the medical stations with fevers of an obscure origin. The difficulty of diagnosing these fevers without the aid of a microscope is obvious. It is essential that a microscope be obtained for use in the Clearing Station.

The most important problem of sanitation for the present is the control of flies. All sanitary measures for the prevention of the breeding and multiplication of flies have been recommended to unit commanders who are doing their best to enforce them. All unit trench latrines, considered to be the most important source of flies, appear to be properly covered but it is still believed that they continue to be sources because it is difficult to prevent flies form laying their eggs and the larvae can succeed in coming out because of their remarkable penetrating power. The use of disinfectants and larvicides is essential in order to eliminate latrines as sources of flies. The supply of disinfectants has been very inadequate and larvicides, such as crude oil, are not obtainable.

The most important problem of epidemiology for the present is the control of malaria. Due to the limited supply of quinine, this drug is not available for prophylactic use.

The number of intestinal and respiratory infections have been relatively few but with the rainy days ahead the increase of these cases is expected. Chances of pollution of sources of drinking water will be greater. Wetting and chilling of the troops cannot always be avoided. The strict observance of proper mess sanitation is an important preventive measure against the spread of intestinal diseases. The troops at the front cannot sterilize their individual mess equipment because of the impracticability of boiling water right there. There seems to be no possible way of doing this except bringing this equipment to the battalion kitchen where they can be sterilized. Adequate shelter from the rain, sufficient clothing to keep the body, especially the feet, warm will have to be provided to offset the tendency to respiratory diseases due to weather conditions.

Some units are not provided with such equipment and supplies as Lyster bags, boilers, and soap which are indispensable to the observance of field sanitation.

Division Surgeon.

About March 1 certain conditions arose which made it necessary to adopt a policy in conflict with the recognized principles of division medical service. The shortage of motor fuel became so acute that normal evacuation procedures had to be abandoned. In addition the sharp increase in the malarial rate, in the dysenteries and nutritional edemas was such that the limited facilities of General Hospitals 1 and 2 made it necessary to limit evacuation in general to two types of case: those requiring a type of treatment not available in division medical installations and those whose return to a duty status was either doubtful or a matter of prolonged hospitalization. Thus due to the fuel shortage, the limited rear-area hospitalization facilities, and in certain instances inaccessibility imposed upon the division medial units, it became necessary to hold and hospitalize cases in forward division areas. The clearing station of each medical battalion became a hospital caring for three hundred or more patients. As the volume of patients increased in early march because of a steady rise in the malarial rate, dysentery, and conditions incident to a starvation diet, it became necessary to utilize the collecting companies for hospitalization purposes. These units set up 100 to 150-bed installations close to the front lines. By the end of March even these additional facilities became inadequate and it was necessary for the medical companies (medical detachments) to hold and treat minor cases in battalion and regimental aid Stations.

By April 1 all facilities for the care of patients in Bataan were strained to their absolute limit to provide oven the semblance of hospitalization for the enormous sick rate. The 91st Clearing Company had expanded to 900 beds and was located about 4,000 yards behind the front line. Trees in and about this hospital were stripped of limbs by passing shells. The 11th Clearing Company was handling over 600 patients. In direct violation of all standard medical tactics, all division medical units were immobilized as result of this forward hospitalization policy. This policy was forced on the medical service by reason of the conditions enumerated above. The perfect cover provided by the tropical jungle flora and the static type of defensive military operations made this policy feasible. However a field medical service of this character, with thousands of patients in the forward areas, made it most essential to keep in intimate touch with the tactical situation at all points of the front in order that immediate and massive evacuation might be effected on very short notice.

Late in January a system of Army evacuation was put into effect whereby division unite ware relieved of the responsibility of transporting cases to the general hospitals. As was stated, every effort was made to keep the number of patients evacuated to minimum. Those cases considered proper patients for a general hospital were collected at certain clearing stations or, in some instances, at a relay station which served two or more clearing companies. Prompt and efficient evacuation was provided by this army medical service.

Medical Supply. Medical supplies were drawn directly from the Department Medical Supply Depot located at km. post 163 on the "East" road by the division medical supply officers. As a result of the loss of organizational equipment by several units early in the campaign, an acute shortage of medical chests existed. Numerous drug shortages developed during the course of the campaign, the most serious of which were the antimalarials. Severe restrictions were placed upon the issue of these drugs. A maximum of eight grams of quinine was allowed per case of malaria. Unit surgeons were required to keep an accurate check of the number of cases in their areas. Every effort was made to prevent hoarding by unit supply officers. Several small shipments of` quinine and at-brine were received by )nears of air transport from Cebu. By this means sufficient antimalarials were procured so that prior to capitulation no cases were denied treatment. Unit medical supply officers were urged to salvage dressings and bandages and to practice extreme economy in the use of all types of medical supply.

Luzon Force. On March 11, 1942, Luzon Force was constituted, and the office of the Surgeon, Luzon Force, was organized March 16th. All medical units in Bataan were included in this Force except General Hospitals 1 and 2, the Philippine Army General Hospital, and the medical Supply Depot. These medical installations remained under the direct control of the Surgeon, U.S. Forces in the Philippines. In the short period of its existence, the office of the Surgeon, Luzon Force, in addition to its routine Army medical functions, concerned itself principally with the following three problems:

a. Plans for evacuation on very short notice of the 7,000 patients located in forward medical division installations: In the event of a break in the defense line, relatively large field hospitals were in danger of being overrun by the enemy. To avoid such a contingency was vitally important because of the character of the enemy, who in a victorious drive would be apt to slaughter both medical personnel and patients. Such tragedies occurred in the Malayan Campaign when forward medical installations were overrun by Japanese troops. As a precautionary measure the 12th Medical Battalion (PS) was transferred from II Corps to Luzon Force to be available as a medical task force in an emergency. Arrangements were made with the Motor Transport and Traffic Control Officers of Luzon Force for the assembly of large convoys of buses and for "right-of-way" priorities over motor highways.

b. Shortage of Medical Supplies: Close contact was maintained with the Medical Supply Depot regarding remaining stocks of drugs and supplies with a view towards allocating them where most needed. Quinine was rationed as stated above. It was possible to smuggle in one or two small shipments of drugs from Manila through secret agents of G-2. A native bark prevalent in Bataan was found which contained the quinine alkaloid. Plans were completed for the gathering, drying, and powdering of this bark and for its use as an infusion in the treatment of malaria, when quinine became exhausted.

c. Decline in the Combat Efficiency of Luzon Force: In the latter part of March the Commanding General of Luzon Force was informed of the fact that the combat efficiency of Luzon Force was fast approaching the zero point as a result of malnutrition, malaria, and intestinal infections; that the tremendous noneffective rate, plus the inability of those on a duty status to undergo any long-sustained physical effort would preclude any successful defense against a determined attack. The factors responsible for the physical deterioration of our forces are briefly discussed below:

(1) Malnutrition: With the advent of the half-ration on January 7th, the troops in Bataan were subjected to the ill effects of a diet that was deficient both qualitatively and quantitatively. The ration averaged about 2,000 calories per day during January, 1,500 calories during February, and only about 1,000 calories during the month of March. The operation of a defense in a mountainous jungle terrain which required hand carrying of supplies over difficult trails and the preparation of positions required a high energy output per man that can be conservatively estimated at not less than 4,000 calories per day. This large caloric deficit resulted in rapid depletion of fat reserves and by March 1st serious muscle wasting was evident in a large percentage of the command, with attendant weakness, loss of endurance, and nutritional edema. Since the principal component of the ration for the Philippine Army troops was milled rice, there was a serious shortage of both protein and vitamins. No fruit was available and the issue of canned vegetables and milk was negligible. All livestock on Bataan, including horses and ponies, we slaughtered and issued. Clinical or incipient beriberi was not only universal by April 1st but in combination with malnutrition and nutritional edema was the cause of the hospitalization of thousands of cases. On April 9th, the date of the capitulation, there was in Bataan only enough food to make one issue of a half-ration.(3) Final Period of Bataan Campaign. (April 2d to April 9th) On April 2, 1942, the enemy launched a heavy attack against the left of II Corps, the immediate objective being Mt. Samat. The attack developed rapidly, with the result that three clearing stations crowded with patients were in danger of being overrun by the enemy. On the night of April 2/3, convoys of about seventy-five buses each, operating under personnel of the 12th Medical Battalion (PS), began the evacuation of all medical installations in II Corps, priority being based on the tactical situation. This massive evacuation was completed on the night of April 5/6. The difficulties encountered by the personnel operating these convoys can be appreciated only by one who has seen the total chaos that existed in forward areas during this period. Roads were congested beyond description. In one instance a convoy was caught directly between enemy and friendly infantry fire.

(2) Malaria: Malaria soon became the primary cause of admission to clearing stations and its incidence rose steadily until be March 1st it reached 500 cases per day. By April1st the rate was approaching 1,000 cases per day and the shortage of quinine was so acute that the issue of the drug was based on an allowance of but eight grams per case. As a result of the inadequate diet, convalescence from the disease was greatly prolonged.

(3) Intestinal infections: As would be expected in an army composed of untrained troops, there was considerable laxness in the observance of the elementary rules of field sanitation. Carelessness in the disposal of excreta was common in front-line areas. There was much promiscuous drinking of unboiled water from streams and pools. Mess gear was not properly washed and sterilized. The result was a rather high incidence of diarrheas and dysenteries. A serious shortage of drugs for the treatment of these conditions existed. Hookworm infestation was present in a large percentage of native troops because of their habit of going barefoot.

(4) Fatigue: an important factor which operated to reduce the combat efficiency of front-line divisions was that of fatigue. The majority of front-line troops received no period of relief or rest in a rear area during the entire campaign. While within regiments there was a rotation of battalions holding the Outpost Line of Resistance, yet even those troops in the regimental reserve line were subject to daily artillery and serial bombardment. The fatigue resulting from constant nervous tension definitely decreased the ability of these troops to ensure a heavy bombardment such as that which ushered in the final drive of the enemy.

The enlisted personnel of the 12th Medical Battalion were largely responsible for the success of this mass movement of patients. Although the margin of safety was in some instances very narrow, no medical installation was captured by the enemy prior to the capitulation on April 9th. A similar mass evacuation was effected in I Corps during the nights of April 5th, 6th and 7th. More than 7,000 patients were transported to rear-area medical installations during the period April 2d to 7th. The burden of initially receiving and messing this large body of patients fell largely on the personnel of General Hospital Number 2, who are deserving of the highest praise for the efficient manner in which they accomplished their task. To increase the bed capacity of this jungle hospital from 2,500 beds to 6,000 in a space of six days is an accomplishment unique in our military medical history. General Hospital Number 1 initially received patients during this period of mass evacuation, but after being more severely bombed was considered unfit for the reception of patients. After the second bombing, bed patients from General Hospital Number 1 were transferred to General Hospital Number 2. To relieve the congestion at this hospital, all rear-area medical units were required to accept patients. A convalescent camp capable of caring for 3,500 patients was organized on April 7th. At the time of the surrender, on the morning of April 9th, there were some 12,000 patients in the service area. During the night of April 8th, surplus medical personnel and all women nurses were transferred to Fort Mills, Corregidor. The principal determining factor regarding the actual time of surrender was the situation of General Hospital Number 2, which with 6,000 patients lay directly in the path of the advancing enemy. On the morning of April 9th, the front was less than four miles from this hospital.